Chloé Jafé

I give you my life

Essay by Emma Lewis

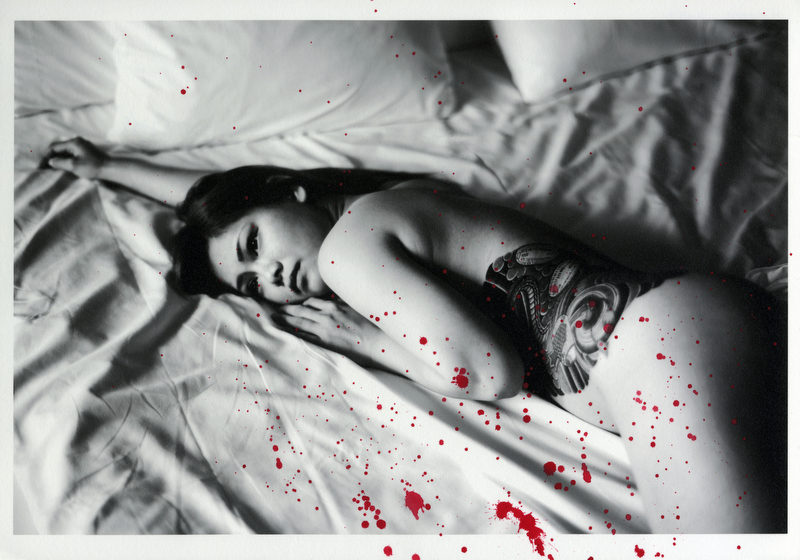

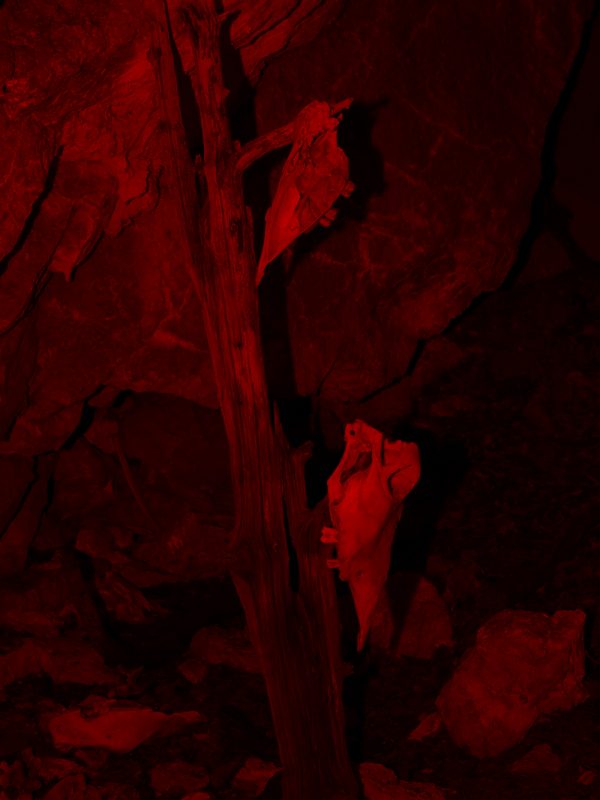

The women in Chloé Jafé’s I give you my life described to her their motivations for getting their tattoos and they’re mostly about love and strength – being in love, falling out of love; feeling strong, needing to feel strong. “I want to live like the man I’m in love with,” says Anna, “I don’t regret anything. In one word, I think they’re really cool!” June got hers at forty because the man she was with had them and “looking at my naked body without any tattoos made me feel weak.” Yuko was thirty-eight, divorced, and she saw them as a way to mark her independence and “discourage certain guys from approaching me […] For the remainder of my life I’ve decided I want to live independently.”

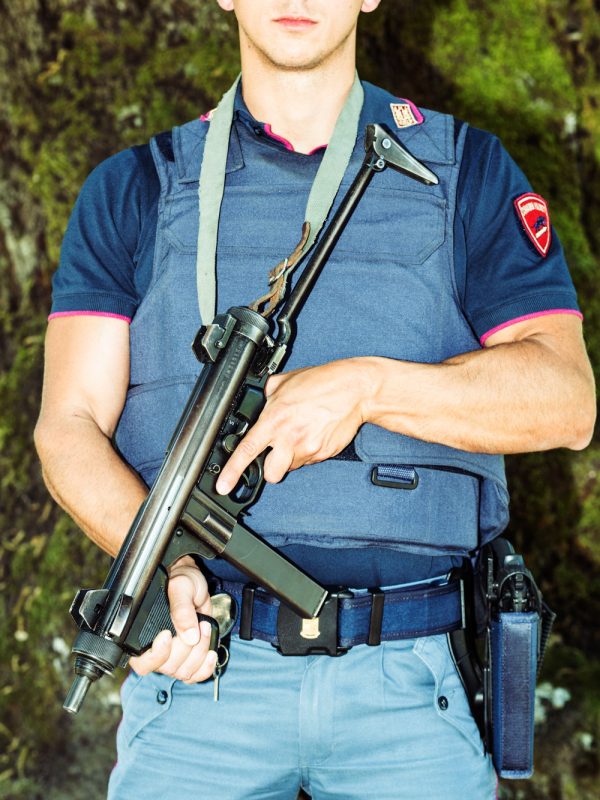

The men to whom these women refer are members of the Yakuza, the international crime syndicate that originated in Japan some four centuries ago and today has around 100,000 members. You’ll have seen these men in photographs: with distinctive tattoos that extend from the neckline down to knees and wrists, they are as photogenic as they are intriguing. Not surprisingly, the organisation and the subculture that surrounds it also make compelling subject matter for film – the Yakuza genre is almost as old as cinema itself.

Despite this pop-culture representation, women’s association with the Yakuza seldom features in any meaningful way. In part this is because, historically, and unlike some other criminal organisations, very little has been known about what their lives are like – though recent memoirs by wives and daughters have gone some way towards lifting the veil. The acclaimed Yakuza Moon by the daughter of an oyabun (family boss), Shoko Tendo – the first autobiography of it is kind to be translated, in 2007, to English – even inspired a glamorous, if wildly inaccurate, movie series.

In 2014, the criminologist Rie Alkemade addressed this lacuna in knowledge with the publication of her study on the wives and girlfriends of the Yakuza, Outsiders Amongst Outsiders, to which she refers in her essay for I give you my life. In her research she found that, with few exceptions, the idea of a Yakuza ‘lady gangster’ is a fiction: their role takes place behind closed doors, managing finances and acting as peacekeepers and mother figures. The term she uses is ‘glue’. To the wives and girlfriends, this work is integral to the running of the clan. But to the men, it is peripheral – and so too are the women.

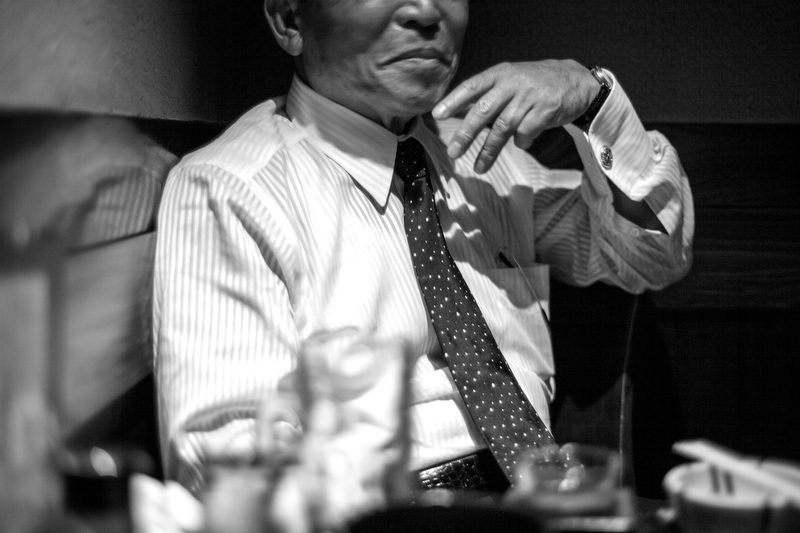

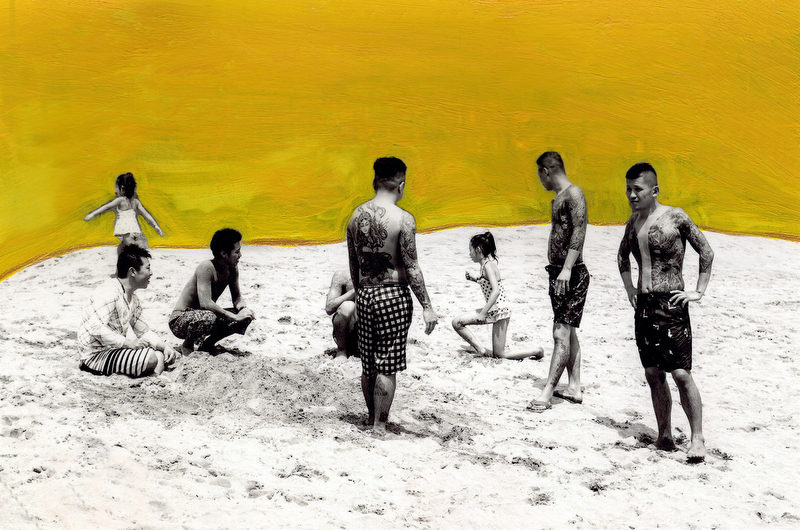

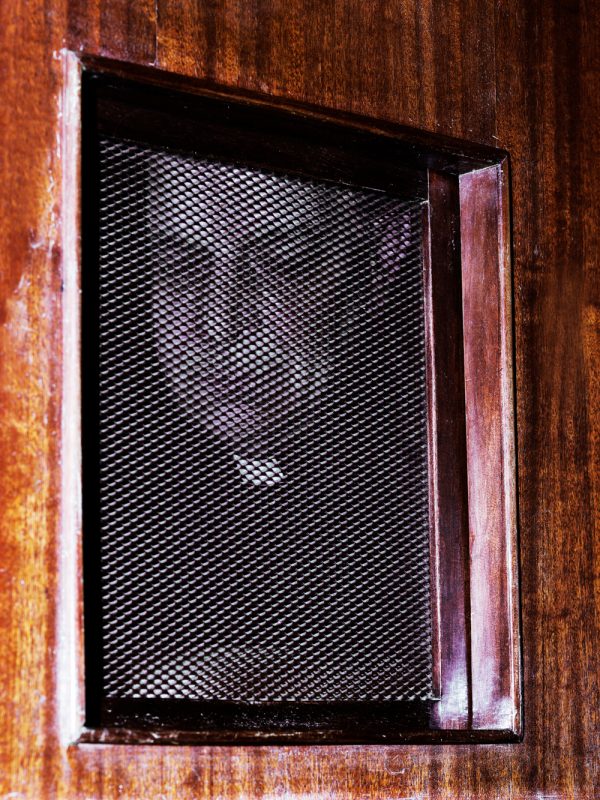

Throughout I give you my life, Jafé highlights this disconnect between how the women perceive themselves and how they are perceived by men. Interested less in the gangster stereotype than the day-to-day life of the clan (who live together under one roof), she shows us scenes to which we are privileged to be privy, but which remain opaque. A group of men, seated and serious. A mealtime, the women in the kitchen. A group of men again, bowing to a man in the back seat of a car. Where mixed groups appear, the women appear to be – as indicated by body language or proximity – subservient. One exception is a photograph taken at the beach, where an ane-san (boss’s wife) is front and centre, tens of tattooed men standing behind her. The hierarchies between a wife and their husband’s subordinates can be complicated.

In this portrait, as in those of the tattooed women – intimate, nude studies and pairs or group shots taken at a traditional festival, where their designs can be seen creeping beyond their clothing – ‘subservient’ and ‘peripheral’ are hardly the first words that come to mind. These women appear self-possessed, independent, formidable even. As Alkemade points out, to tattoo their bodies takes courage not only because in conveying an allegiance to the Yakuza they place themselves outside of mainstream society, but also because the Yakuza men will never truly accept them as members. If her title Outsiders Amongst Outsiders highlights this limbo, then Jafé’s I give you my life begs the question: and for what?

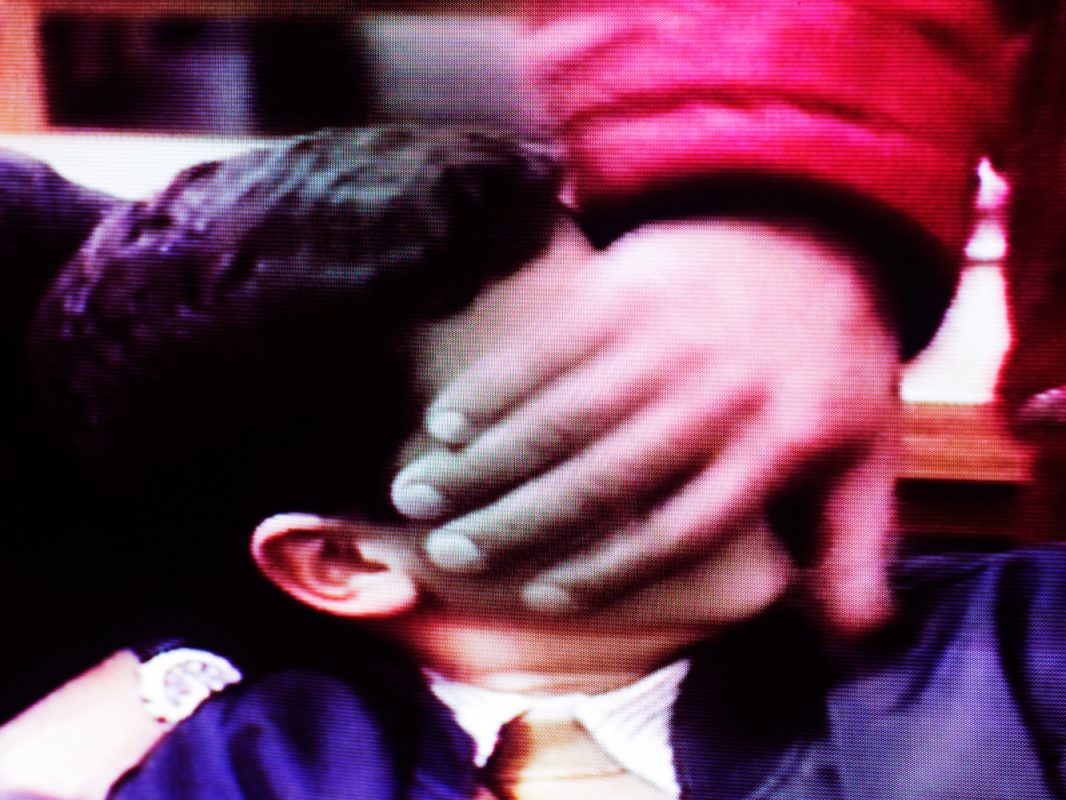

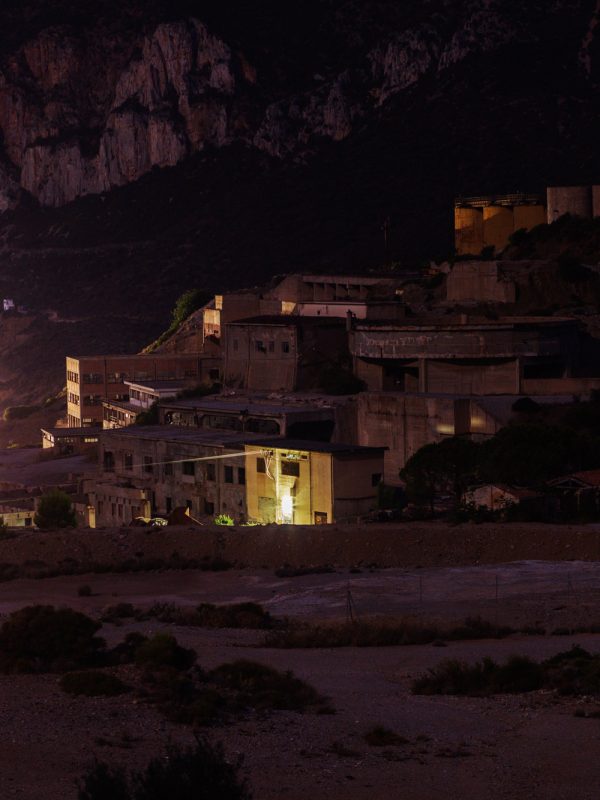

In many ways, Jafé’s is a project about access – how the photographer found her way to her subject, and the dynamics that played out when she got there. When she arrived in Tokyo, she didn’t speak the language or have a fixer, only the determination to reach the women who orbited the world that she had watched in so many films and read about in Yakuza Moon. She also knew that because women aren’t permitted to invite guests into their home, she would have to go through the men.

Jafé began her journey in the city’s red-light district, where she met men who were low down in the syndicate’s ranks and to her, felt more dangerous than useful. There were introductions and tip-offs from friends and acquaintances – a tattoo artist, a hairdresser. She got a gig as a hostess in a bar, the only non-Japanese person to work there, but had her bag stolen, didn’t feel safe. Two years down the line, it was a chance meeting at a festival that led her to the oyabun. Gradually, Jafé was allowed access to his inner circle and then, only when she gained his trust, she was granted access to his wife.

In a project where gender disparity appears to be so acute, it is interesting to consider the ways in which the photographer’s relationships with the men and women differed. To access the upper echelons of a Yakuza clan is no mean feat, but you sense there was a vanity involved on the men’s part. Jafé must have amused them. She had to be charming, deferent, and harmless. Yet to the ane-san, this young, foreign, woman that her husband was taking to dinner wasn’t necessarily such a benign presence. Aware that the wives and girlfriends viewed her with suspicion, Jafé worked her way in carefully, making friends and navigating through a very particular set of social codes and cues. The portraits that result from this gradually built trust are sensitive, considered and, importantly, they feel collaborative. “You work on luck,” she says, reflecting on that chance meeting with the boss at the festival. But of course, there’s more to it than that. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Chloé Jafé

—

Emma Lewis is an Assistant Curator at Tate Modern, where she organises exhibitions and displays and is responsible for researching acquisitions for Tate’s photography collection. Her book Isms: Understanding Photography was published by Bloomsbury in 2017.