Photo50 2024

Grafting: The Land and the Artist

Exhibition review by Fergus Heron

In 2024 London Art Fair’s annual Photo50 exhibition was guest curated by Revolv Collective. Titled Grafting: The Land and the Artist, it showcased mainly emerging artists, with the commonalities across the range of presented works circling around ideas of situation, proximity and entanglement with land. The work featured slow and meticulous processes in its making, and, as a result, invited close, detailed and sustained attention, writes Fergus Heron.

Fergus Heron | Exhibition review | 24 Jan 2024

In Landscape and Western Art (1999), Malcolm Andrews speculated ‘as a phase in the cultural life of the west, landscape may already be over’. Andrews drew upon insights by geographer Denis Cosgrove that ‘landscapes can be deceptive’, and John Berger’s well-cited passage that ‘sometimes a landscape seems to be less a setting for the life of its inhabitants than a curtain behind which their struggles, achievements and accidents take place. For those who, with the inhabitants, are behind the curtain, landmarks are no longer geographical but also biographical and personal’. Recent literature exploring how artists make sense of place, including work by Susan Owens and Alexandra Harris, build upon such thought, focussing on the ways in which contemporary artists work with renewed attention to their immediate localities, in many cases concentrating on how their own, and their communities’, lived experiences of place involve co-dependent human and non-human natures.

It is with this sense of place that London Art Fair’s Photo50, guest curated by the photography organisation Revolv Collective, presented Grafting: The Land and the Artist. Featuring mainly emerging artists, the commonalities across the range of selected works were those of situation, proximity and entanglement with land. Most of the work featured slow and meticulous processes in its making, and, as a result, invited close, detailed and sustained attention.

The curatorial approach taken focussed upon the detail, fragment and perhaps, above all, the matter of land. These considerations were situated in close dialogue with the materials of photography, primarily in its analogue forms, as well as materials and processes at the edges of, and that exceeded, the medium. The collection of works was drawn from a range of independent projects made in numerous ways from artist residencies to academic research. All projects approached land as the actual matter and form of places lived and worked. Here, there was limited, if any, sense of landscape, that is, the kind of picture made according to art historical conventions of the picturesque or sublime that frame views of land at a distance for remote contemplation. Where landscape was present, it was as reference or critique.

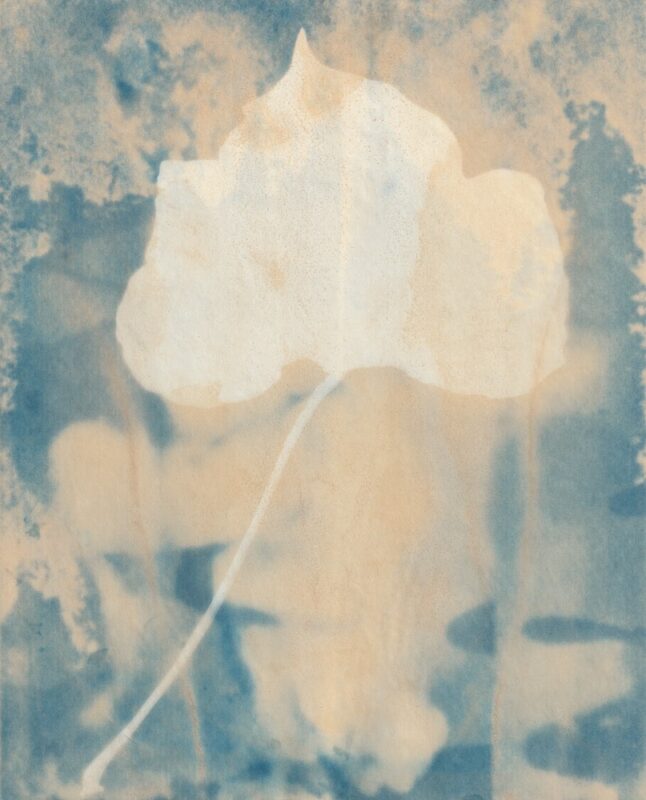

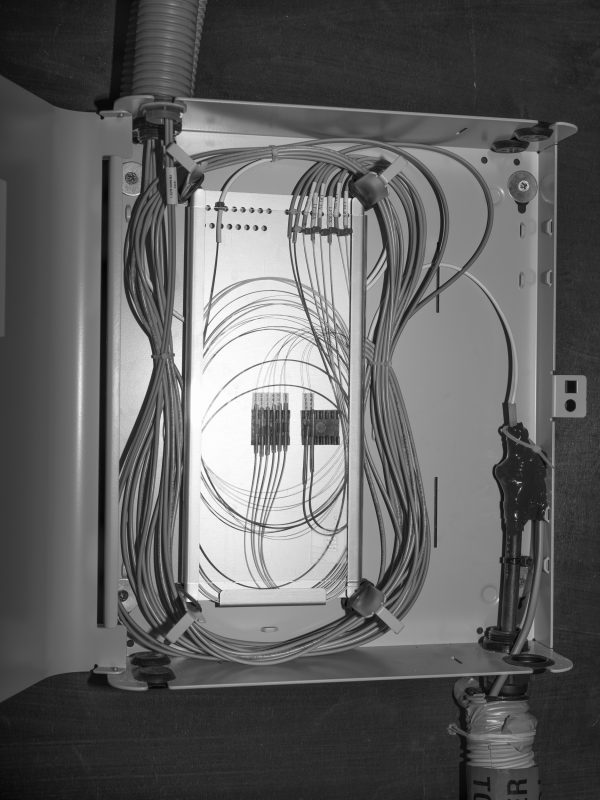

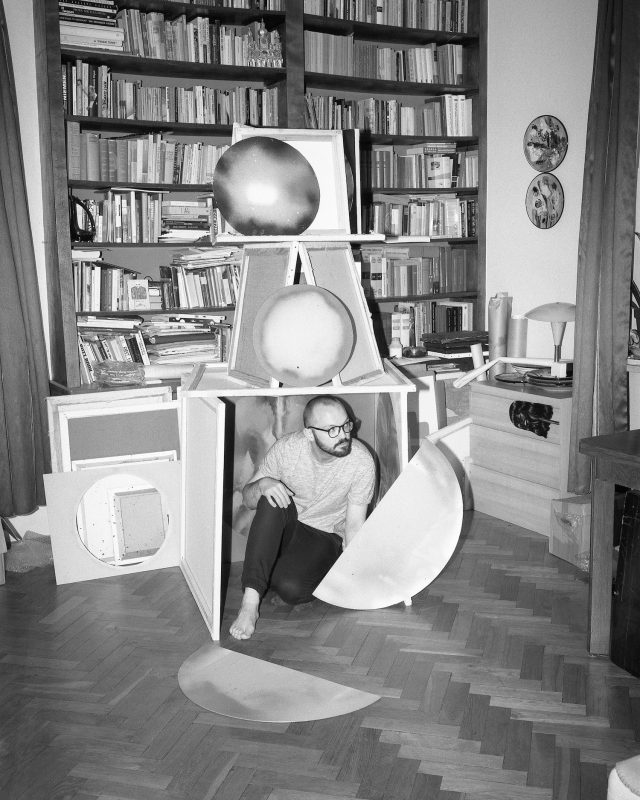

Amongst standout works was Eugénie Shinkle’s Ideal City (Somebody Else’s Landscape). This work was constructed from individual 35mm colour contact prints hand sewn into a large-scale piece presented upon a freestanding frame. Corresponding through its colours with paintings by JMW Turner, the conjunctions of early industrialisation, the awe-inspiring forces of the natural world and the emergence of photography were in dialogue. Other works referred to the early years of photographic exploration within which plants featured heavily as subjects; Marie Smith’s Extraction: In Conversation with Anna Atkins comprised cyanotypes inspired by this key figure that depict leaves and plants from the Horniman Museum in London using herb-based developers to process the images, bringing photographic subjects and processes into close relation. Amongst works produced collaboratively was Seed Pod by Joshua Bilton. This project brought together stories of school children involved in a series of workshops imagining themselves transforming into plants, trees, water, birds and seeds in response to water ways forming part of their immediate environment.

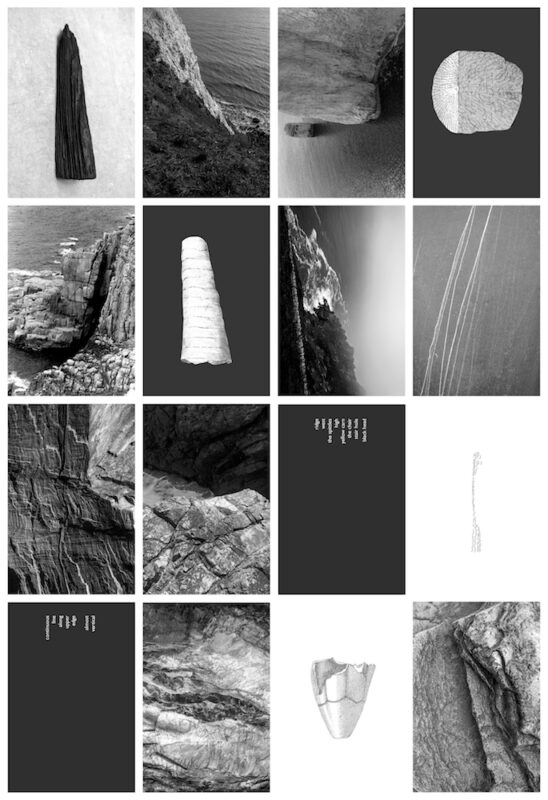

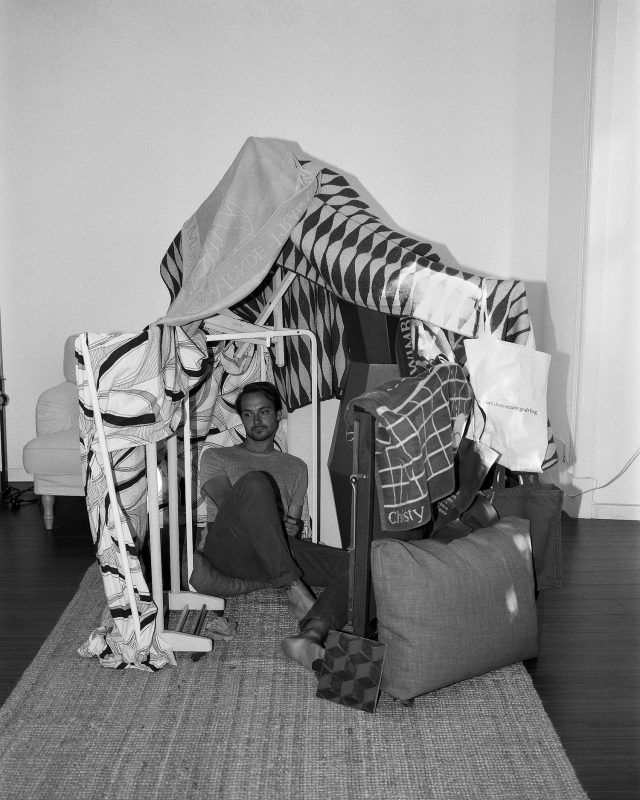

Collected in a box, the stories and poems accompanied delicate sculptural earthstone seeds and Polaroids used to record performances and workshops. Laid out on a modest trestle table in the exhibition space in rows, grids, columns and a circle, the Polaroids showed children’s hands inscribed on the print rebate with their names, and the seed pieces in connection formed poignant commentary on notions of community, hope and possibility. Rowan Lear’s A Sudden Branching featured silver gelatin prints showing fragments of land surfaces and forms mounted on the underside of wooden shelves. The shelves, painted bright green and fixed to the wall, on their topsides supported ceramic stems made from grafting together two types of clay. To see this work fully demanded movement of the body in ways that alluded to natural processes and defamiliarised conventions of looking and display. With great subtlety, and at first apparent simplicity, this work engaged multiple complex ideas about human relations with the natural world. Jackson Whitefield’s highly refined mixed media monochrome works placed land art and landscape in dialogue.

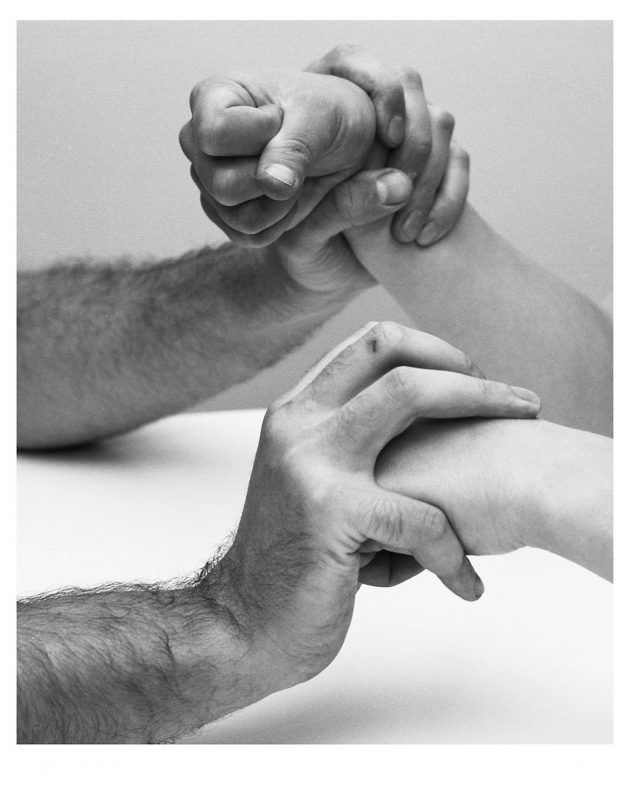

Hannah Fletcher and Alice Cazenave’s collaborative project (is)land featured a collection of 16 beautiful direct positive prints exposed in waste film canister pinhole cameras, developed with plant-based chemicals and fixed using salt evaporated from the Baltic Sea. Without enlargement, and with the imagery featuring landscape views and surface markings from their process with near equal emphasis, photographic technology was situated within, and inseparable from, the world it shows. The placement of the series next to another of Fletcher’s works, a sculpture constructed upon principles for silver reclamation from exhausted photographic fixer, created dramatic contrasts in scale and materials. In relation, these works situated photographs generated from the land, and offered comment upon the environmental consequences of photography’s materials and techniques, demonstrating how reworking the actual development process of photography towards different futures can be possible.

Within the fair, Photo50 was difficult to find. Once located, the work was installed along a set of display walls, effectively forming a linear sequence from left to right. There was limited space in which to give each piece of work the kind of concentration it deserved. Extra peripheral activity was all too apparent with many distractions. Nonetheless, once adjusted to the location, the strength of the collected works, the variety of approaches and their qualities emerged. Much of the work was complex and detailed, often small in scale, or made up of many smaller constituent parts, which helped activate ways of looking that alternated between, and in the best examples effectively balanced, critical engagement with the key underpinning curatorial issues and the kind of reverie that images of the natural world at their most powerful can stimulate. As a collection of work, the show made visible the shared agencies and interdependencies of human and non-human natures through photographic images; those with and from the natural world. Visible too were the aesthetic qualities of photographic materials that in many different ways touch the natural world. ♦

Grafting: The Land and the Artist ran at Photo50 at London Art Fair from 22 – 26 January 2024.

—

Fergus Heron is Course Leader for MA Photography, leads the Photography Research Group and is a Research Supervisor in the School of Art and Media at the University of Brighton. He studied at the Royal College of Art, London, and the University for the Creative Arts, Farnham. Exhibitions featuring his work have taken place internationally at venues including: Tate Britain, London; Centre for Contemporary Art and the Natural World, Exeter; Royal West of England Academy, Bristol; Museum for Contemporary Art, Roskilde, Denmark; and K3 Project Space, Zurich, Switzerland. His work is included in the anthology Emerging Landscapes (Routledge, 2014). He selected Photography Culture: Photography and Landscape (The Photographer’s Gallery, London, 2018), edited Visible Economies (Photoworks, 2012) and is a contributor to A Companion to Photography (Blackwell, 2020).

Images:

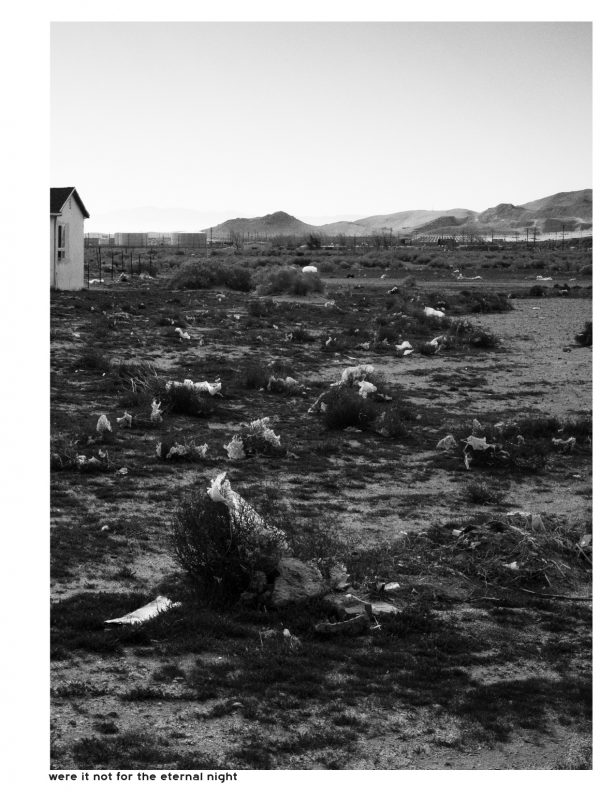

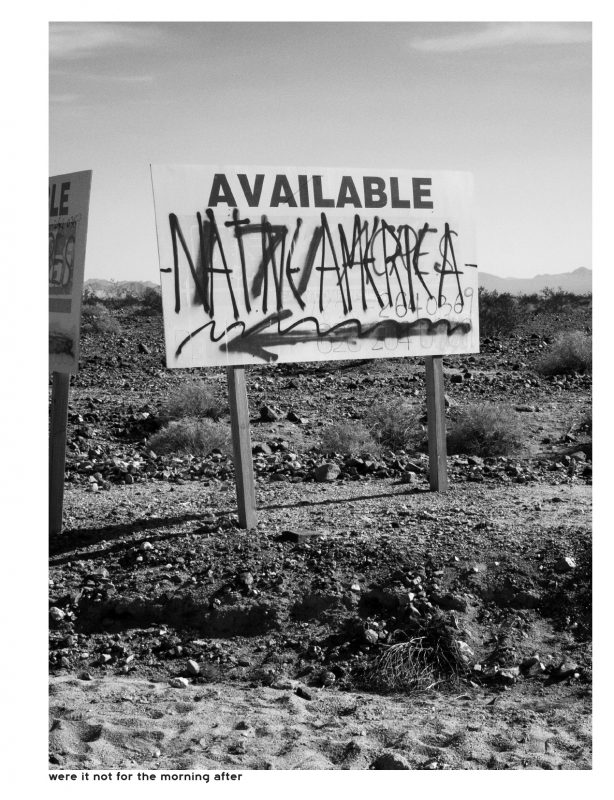

1-Eugénie Shinkle, Ideal City (Somebody Else’s Landscape), 1998. Image courtesy of the artist.

2-Eugénie Shinkle, Ideal City (Somebody Else’s Landscape), 1998. Image courtesy of the artist.

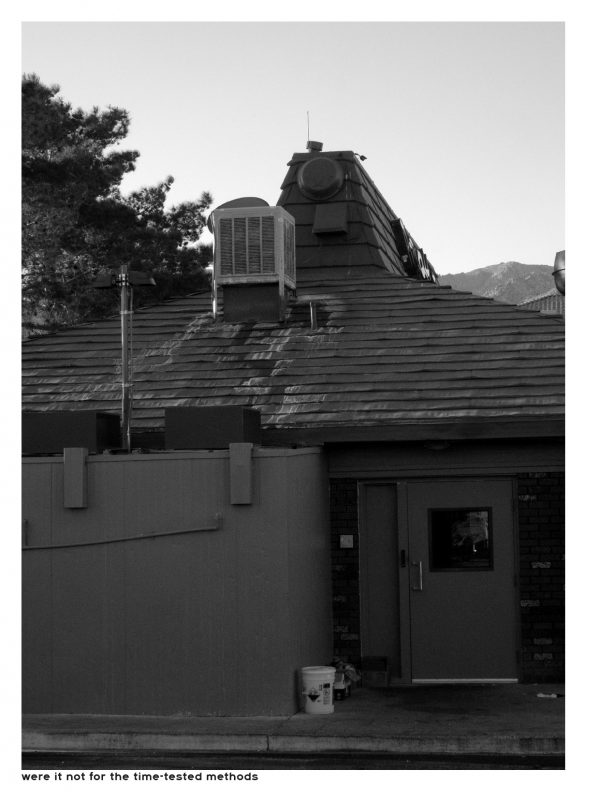

3-Hannah Fletcher, Alice Cazenave, (is)land, 2022. Image courtesy of the artists.

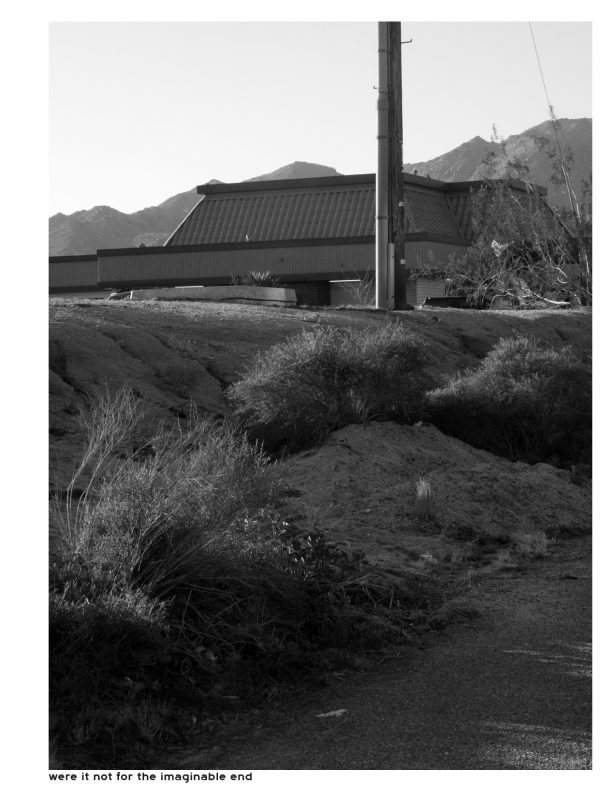

4-Jackson Whitefield, Imprint I, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist.

5-Marie Smith, Extraction: In Conversation with Anna Atkins, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist.

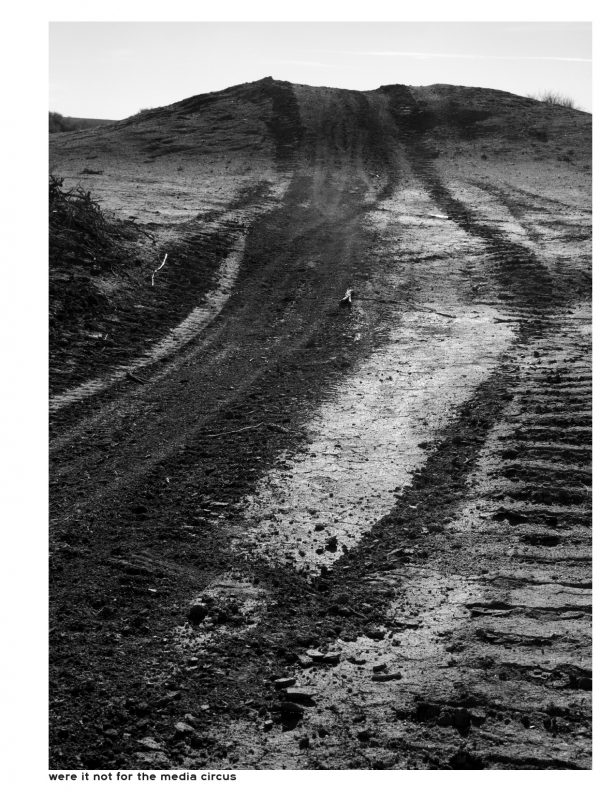

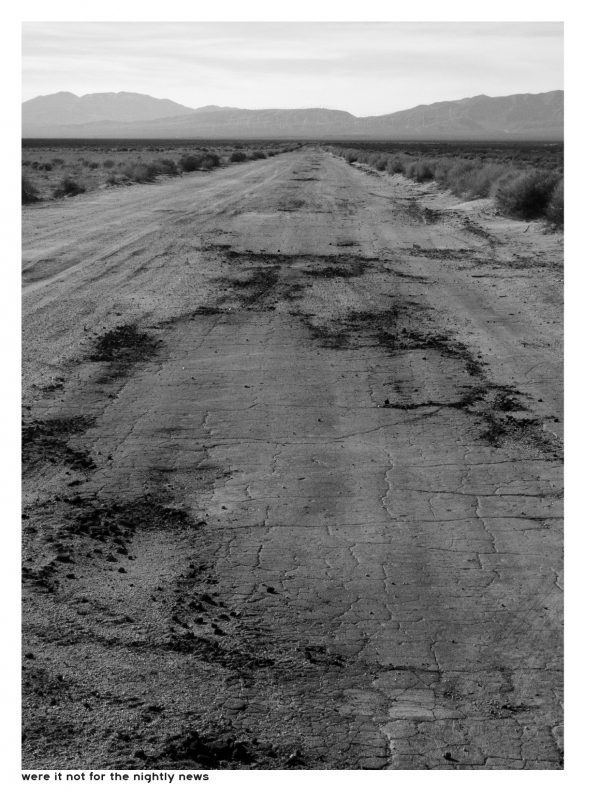

6-Edd Carr, Yorkshire Dirt 1, 2022, 3min16.

7-Tamsin Green, cliff, 2021.

8-Victoria Ahrens, Purpurea, 2023.