Francesca Catastini

The Modern Spirit is Vivisective

Book review by Gerry Badger

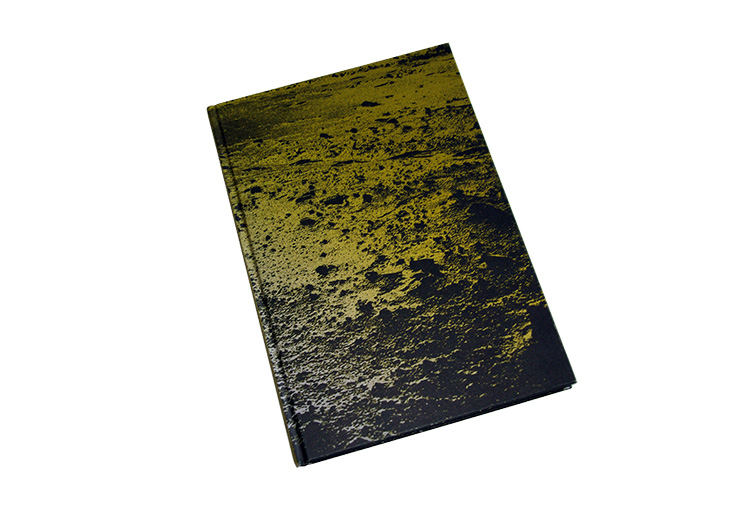

The first question one has of this book by the Italian photographer Francesca Catastini, which won the ‘Dummy’ prize at this year’s Vienna Photobook Festival, centres upon its title. The book is a meditation in images and text upon the process of studying human anatomy, which is essentially the same today as it was in say the famous Anatomical Theatre in Bologna University, constructed in 1637. Except perhaps for that fact that a paying public no longer attends these events, although there was of course the highly public dissection on Channel 4 in 2002 by Gunther von Hagens.

But here the operative word is dissection. The study of anatomy is based primarily upon empirical observation of the body’s inner parts, obtained by dissecting corpses. Catastini’s title however, The Modern Spirit is Vivisective, refers to vivisection, the cutting up of living bodies and a practice confined mercifully to the experiments upon live animals that so many of us find appalling.

Catastini’s title in fact derives from the modernist manifesto of the young James Joyce, a former medical student. In his posthumously published novel, Stephen Hero, Joyce lauds vivisection as the most modern strategy an analytical artist can deploy. The novel was published in 1944, although Joyce could hardly know that at the time the Nazis were using vivisection in diabolical experiments upon human beings in the camps.

Hopefully, Francesca Catastini is using the term in a metaphorical sense, in which she as a living artist is creatively dissecting the practice of dismembering and analysing corpses, musing upon a discipline which, in the early days, was linked more to natural philosophy than to medicine per se. And of course was a prerequisite for study by artists, such as Leonardo or Michaelangelo.

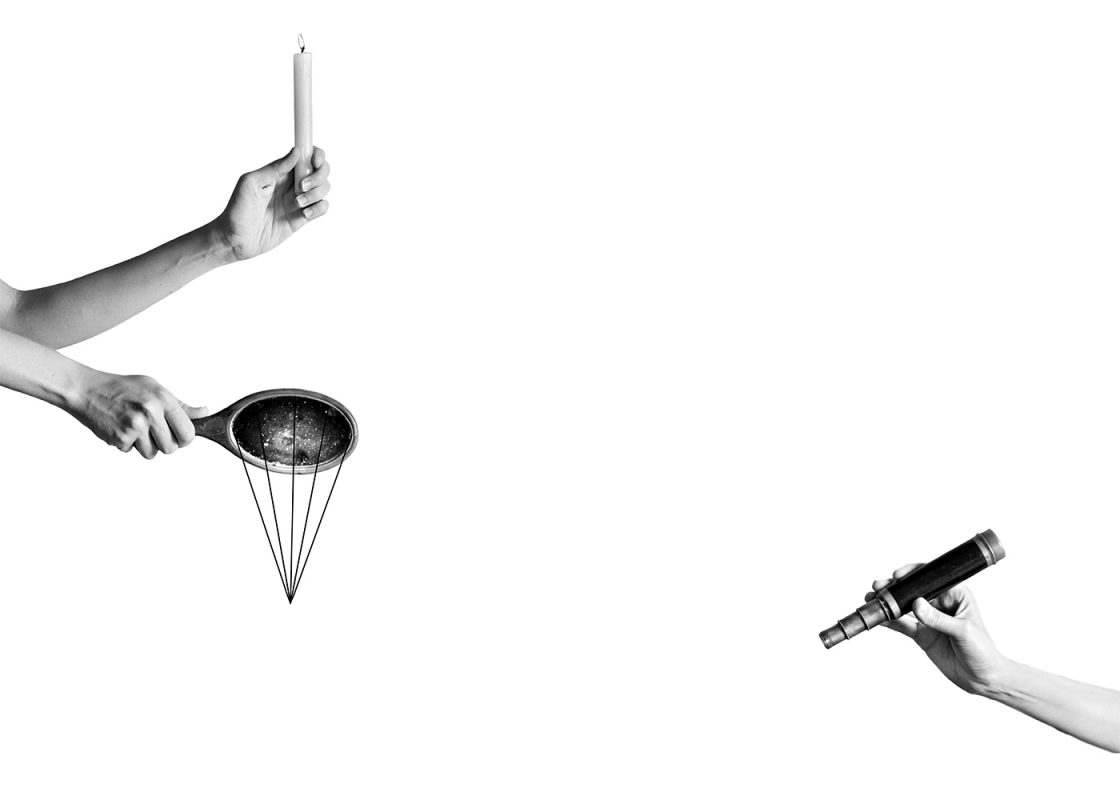

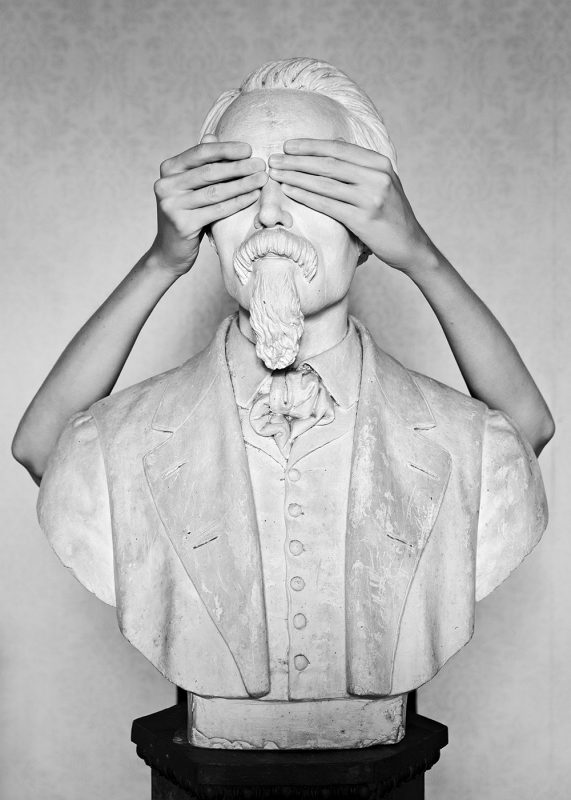

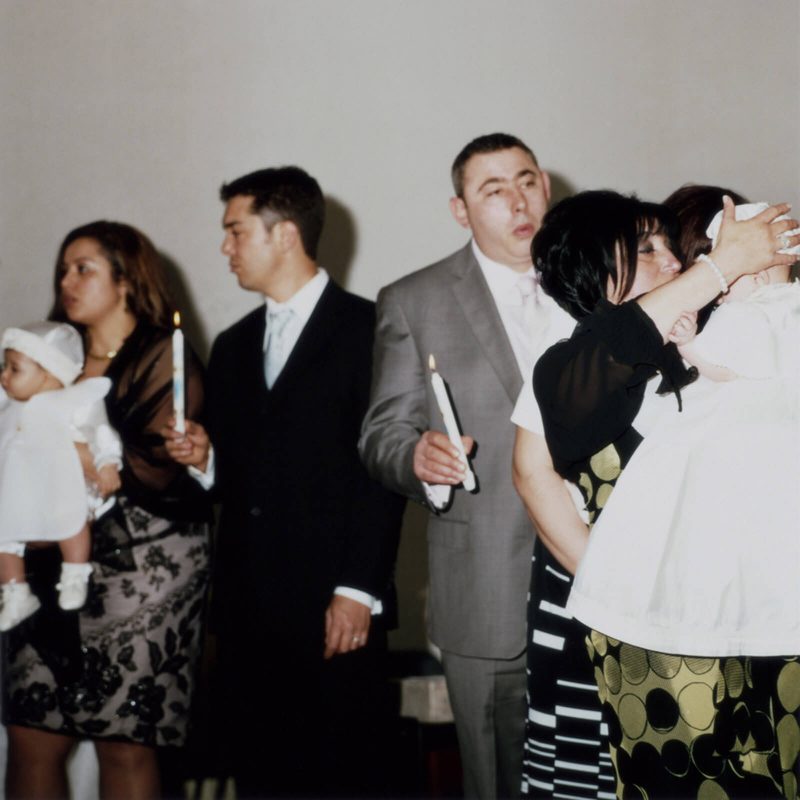

But already, we can see that this is a most unusual photobook. Beginning with the title itself, we are drawn into an intriguing web woven by Catastini, a web of image and word, metaphor and oxymoron, as she combines found vernacular photographs of old anatomy lessons with illustrations from Renaissance anatomy manuals, and sprinkles these with scientific, literary, and philosophical quotations. And of course, she adds her own photographs, scrupulously neutral large format images of some of the those famous Italian anatomical theatres, as well as some subtle photocollages.

The book, edited by Federica Chiocchetti, is divided into five sections, each corresponding to the five stages involved in dissection as detailed in the old treatises, each ‘chapter’ being framed by Catatsini’s interiors. The five are entitled respectively On Looking, On Canon Lust, On Touching, On Cutting, and On Discovery. But the narrative, while not exactly freewheeling, is, shall we say, a little whimsical, and some of the images have little interventions by Catatstini that one could easily miss. The Looking chapter, for instance, contains the expected diagrams of optical instruments, microscopic slides and so on, but also emphasises the theatrical aspect of the business. There are a couple of found photographs from the John Hopkins Medical School dating from 1943, one showing a group of rather serious anatomy lab students. A rip in the photographic emulsion ‘makes a mess’ of one girl’s face, which may or may not be relevant to the subject, yet nothing Catastani does is without thought, so I take it that it is. In the other picture from John Hopkins, a cheerful young lady holds a severed limb like a guitar. Anatomy students are a different breed.

On Canon Lust is not quite what one might think. Sex crops up frequently in both anatomical studies and in Catastini’s imagination, but this section is in effect about anatomy’s relationship to art, and the obsession that both art and medicine have had with the perfect body, although paradoxically medicine is most often about the imperfect body. The section begins with a photograph of the young Ronald Regan (1940) – regarded as having a perfect physique when young – modelling in a life class. There is also an amusing passage quoted about never pointing out to students that you have a corpse with six fingers on a hand. Hide it – or maybe cut off the offending finger.

Catastini’s narrative is laced with such humour. On Touching has two images of blind people learning anatomy, by touching a skeleton. I don’t know if they go on to handle a corpse on the dissecting table, but that thought, and even handling a skeleton, somehow makes me squirm, although of course it shouldn’t.

In this section, there is also a French illustration of a kneeling man (hopefully a doctor) with his hand up the skirt of a remarkably insouciant woman. This illustration amused me because it reminded me of the only seaside postcard I know to feature a photographic joke. A young man on his knees has his hand up a woman’s black skirt. She is saying, ‘that’s the last time I let you change your film.’ The postcard is dated not only by its sexism but the idea of the film changing bag (no double entendre intended).

I could go on about this intriguing and engaging book, but one of it delights is that it is a cabinet of curiosities, and therefore surprises, so I may have given too much away already. I am impressed, for example, that Francesca Catastini didn’t opt for the obvious, with images of an échorché – the flayed corpse – or, even closer to home, something from the famous anatomical wax sculptures of Florence or Bologna.

Some felt in Vienna, that with such a plethora of drawn and engraved illustrations, whether this was actually a photobook, but does it matter? It pushes the boundaries of the photobook, not by containing the fewest ‘photographs’ (there are more than one might think at first glance) but by being so intelligent. In an era when the photobook seems all about flashy form and empty content, and drearily focused upon the self and little else, it is a pleasure to see a photobook, contentedly sober in design, looking outside itself, and engaging the brain as well as the eyes. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist © Francesca Catastani

—

Gerry Badger is a photographer, architect and photography critic of more than 30 years. His published books include Collecting Photography (2003) and monographs on John Gossage and Stephen Shore, as well as Phaidon’s 55s on Chris Killip (2001) and Eugene Atget (2001). In 2007 he published The Genius of Photography, the book of the BBC television series of the same name, and in 2010 The Pleasures of Good Photographs, an anthology of essays that was awarded the 2011 Infinity Writers’ Award from the International Center of Photography, New York. He also co-authored The Photobook: A History, Vol I, II and III with Martin Parr.