Oliver Frank Chanarin

A Perfect Sentence

Exhibition review by Mark Durden

In response to Oliver Frank Chanarin’s new exhibition at FORMAT23, Mark Durden argues that the artist’s conceptual trick of revealing the printing process is a means of vivifying a conventional photographic portrait practice and chimes with the project’s quirky index of Britishness.

The photographic portrait is arguably the central genre and tradition of photography. Oliver Frank Chanarin offers a new take on this important and longstanding tradition through an old process in A Perfect Sentence, his exhibition at The Museum of Making, as part of the 11th edition of Derby’s FORMAT International Photography Festival.

Chanarin’s portraits of people in Britain have been drawn from multiple journeys across the country over the last year, commissioned and produced by Forma, in collaboration with an impressive network of partner arts organisations and funders. This show of around 100 colour photographs amounts to about a third of the pictures that make up the total project. It will be followed by further exhibitions as well as a publication from Loose Joints.

August Sander was an initial point of departure, but, as Chanarin acknowledges, “the cool archival approach” soon stopped being helpful. As it evolved, he felt his work was closer to that of Sander’s contemporary Helmar Lerski. An actor and cameraman, Lerski made multiple portraits of his sitters, with a variety of expressions, people drawn from the streets of Berlin — beggars, hawkers, street cleaners, housemaids, porters — but abstracted from their social roles through his aesthetic vision. Chanarin’s portraits are not as manipulated as Lerski’s. But in the theatre and dramaturgy of many of his subjects, one senses the Lerski connection. Chanarin is not so much interested in people’s social role; despite having visited factories, there is little interest in describing labour and working conditions but instead a presentation of British life as bizarre spectacle.

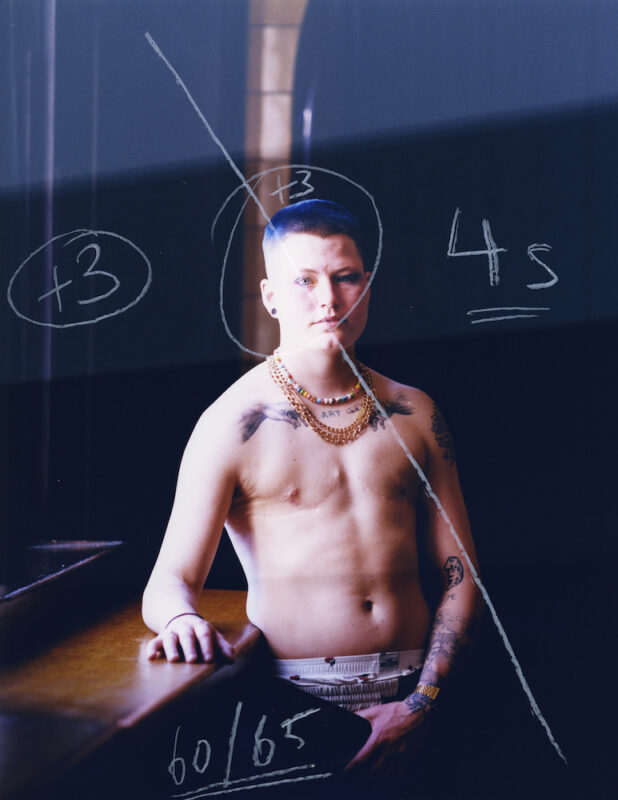

The work sets up a friction between the familiar convention of the photographic portrait and a conceptual strategy that makes visible the process of C-type colour printing. The colour casts, bands of differing exposure, double printing, as well as all the markings and annotations upon many of the prints, affirm and display the darkroom work of making these portrait pictures — the craft and labour and time integral to this now vintage, noxious and disappearing chemical process. In resisting the closure and fixity of the final image, these imperfect images, according to the wall text that accompanies the show, are intended to “allude to the mercurial nature of identity and the subjectivity inherent in image-making.” But great photographic portraits have and will always continue to draw attention to the mercurial nature of identity. I don’t need to see the process of the portrait’s printing production to be made aware of this.

What then does making the printing process visible do? Is the disclosure of the colour printing process intended to revive interest in an old and disappearing process? Chanarin’s turn to the darkroom does seem to chime with the way in which he describes this project. After a successful two decades’ long artistic collaboration, he wanted to return to what drew him to photography in the first place: “encounters with strangers and the beautiful accidental moments that come with getting lost in the world with a camera.”

The visibility of the printing process does make us aware of colour as a filter, as an artificial application. In this respect, it links up with the make-up abundant and excessive on some of the faces he has pictured. There is a certain aesthetic pleasure and joy in the deviation from the straight colour print and it could be seen in keeping with the Photoconceptualists’ dismantling and disclosure of photographic form. At the same time, it could also be seen just as a gimmick, a means of vivifying a conventional photographic portrait practice.

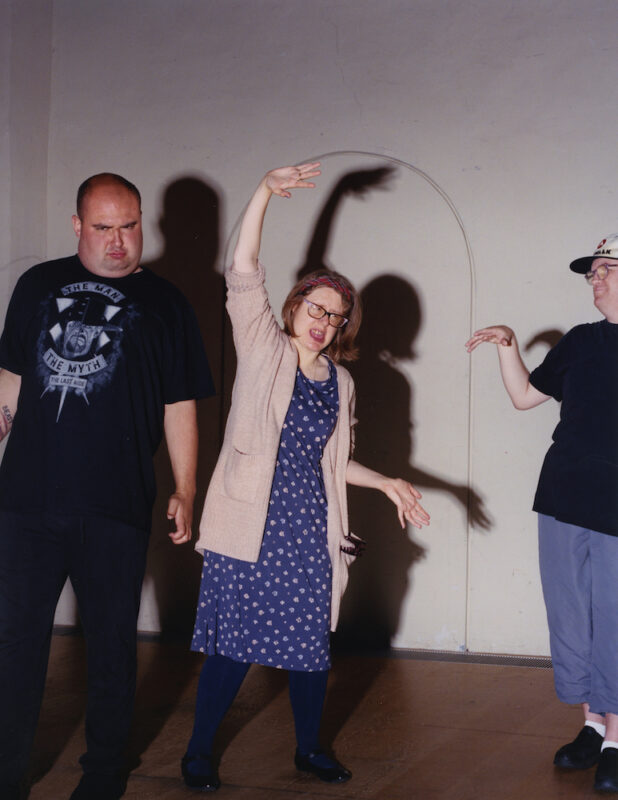

Drawn to the theatrical, the strange and the unusual, Chanarin’s is a carnivalesque portrait of Britain — encompassing carnival troupes, protestors dressed as chickens, model railway enthusiasts, a volunteer couple at a local zoo with snake and tarantula, the bondage rituals from the Shibari class for a local fetish community and pictures he has made with volunteers of the Casualties Union, people who use make up and acting skills to play the role of casualties for the emergency services and medical profession. The latter portraits introduce a realm of simulation, confuse and unsettle the documentary basis of the project. Chanarin’s interest in performance and dramaturgy in the portrait transaction is evident not just through all those he pictures costumed and made up. It is also there in less adorned subjects: his brief sequence of portraits made in homeless shelters, the calm communique of the man who makes enigmatic gestures and signs with his hands to his photographer (and us) or the woman whose nervous energy means she cannot hold a pose.

For this show, the photographs are all printed the same size (10 x 8 inches) and framed the same way. Their arrangement and sequencing are however playful and break uniformity — pictures are hung in corners, above eye level and, in one, presented as a diagonal drawn out across a long wall. The diagonal line of pictures presents us not with portraits but with photographs of a seemingly random assortment of objects and details drawn from the communities he has been given access to and places visited — a quirky index of Britishness ranging from stacks of buttered white toast to a Rolls Royce plane engine.

None of the photographs on show have labels or captions. Instead, there are a series of 12 short, condensed stories delivered as a spoken narrative by the photographer and accessed on our mobile phones through a QR code. Chanarin’s poetic, open-ended and suggestive auto-narratives provide an effective alternative to captions and convey often interesting reflections, thoughts, ideas and observations from his travels across the UK, meeting and photographing different people. They are also refreshingly open and honest in their admission of the difficulties and problems of picturing people. After a photography workshop with teenagers and posting a portrait of a student helper on Instagram, he tells us how he had to remove the image and destroy all photographs made with the teenagers because he had broken safeguarding issues.

A happier story is attached to his portrait of three young women in bikinis standing before rocks on a beach, all hands raised shielding their eyes as they look into the sun. When he wrote to them with a copy of the photograph, one of the bathers said how proud and happy she was to have her picture taken, how the picture gave her confidence in her own looks, without make up. Chanarin exhibits two versions of this photograph side by side, one clearly printed and the other with bands of different exposures darkening the picture and the faces of the bathers. In the anecdote about the picture being liked, he does not say which version he sent her, which raises questions about the interest his subjects would have in the prints bearing marks of the process of their production. One picture of a housing estate has the words “bad” written up on it, a commentary that inevitably could also be taken to not just be a remark about the print.

Funding bodies love art with social impact but much art that is “community-driven” or “socially engaged” tends to be over-determined by the worthiness of its cause and message, and often does little more than replay prejudices and assumptions about the communities represented whilst never really overcoming the gulf and distance between the artist and the people that have become their subject. From the long list of credits and acknowledgments given in a wall panel for this exhibition, this project, made in collaboration with no less than eight UK organisations, would appear to have been both well-funded and supported, involving teams and networks of people to make it happen, right down to the designer and graphic artist (two people, not one) of A Perfect Sentence’s identity. Yet while there are reflections on the problems and issues around representing people within his spoken narrative, it is still dominated by a rather conservative and romantic portrait of the lone artist photographer as “wanderer”, losing himself in the strange experiences and encounters opened up by life in regional towns and cities in Britain. The canny conceptual trick of showing us the printing process also nicely matches the project’s overall romantic premise: implying a freedom from rules and templates. It fits with the eccentricities of the folk on show and Chanarin’s left-field vision of Britain. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist, The Museum of Making and FORMAT International Photography Festival, Derby © Oliver Frank Chanarin. Commissioned and produced by Forma, in collaboration with eight UK organisations. Supported by Arts Council England, Art Fund and Outset Partners.

A Perfect Sentence ran at The Museum of Making, as part of FORMAT International Photography Festival, until 3 September 2023. A Perfect Sentence (Part II) runs at KARST Gallery, Plymouth, until 18 Match 2024.

—

Mark Durden is a writer, artist and academic. Together with David Campbell and Ian Brown, he works as part of the art group Common Culture. Since 2017, Durden has worked collaboratively with João Leal in photographing modernist European architecture, beginning with Álvaro Siza. He is currently Professor of Photography and Director of the European Centre for Documentary Research at the University of South Wales, Cardiff.

Images:

1-Oliver Frank Chanarin, Marine Academy (Year 10) (2023) © the artist.

2-Oliver Frank Chanarin, with Elaine (2023) © the artist.

3-Oliver Frank Chanarin, with anon (2023) © the artist.

4-Oliver Frank Chanarin, with Untitled (2023) © the artist.

5-Oliver Frank Chanarin, with June (2023) © the artist.

6-Oliver Frank Chanarin, with Mark (2023) © the artist.

7-Oliver Frank Chanarin, with Fay, Maisie and Robyn (2023) © the artist.

8-Oliver Frank Chanarin, Untitled (2023) © the artist.

9-Oliver Frank Chanarin, with Adam (2023) © the artist.

10-Oliver Frank Chanarin, with L Cpl Oliver (2023) © the artist.

11-Oliver Frank Chanarin, with Joshua, anon and Andrew (2023) © the artist.