Sayuri Ichida

Absentee

Book review by Callum Beaney

Callum Beaney argues that Sayuri Ichida’s medium-centric presentation of negative inversions, repetition and silver ink return readers not to photography as the main subject, but towards a physical body amidst the distress of its representation.

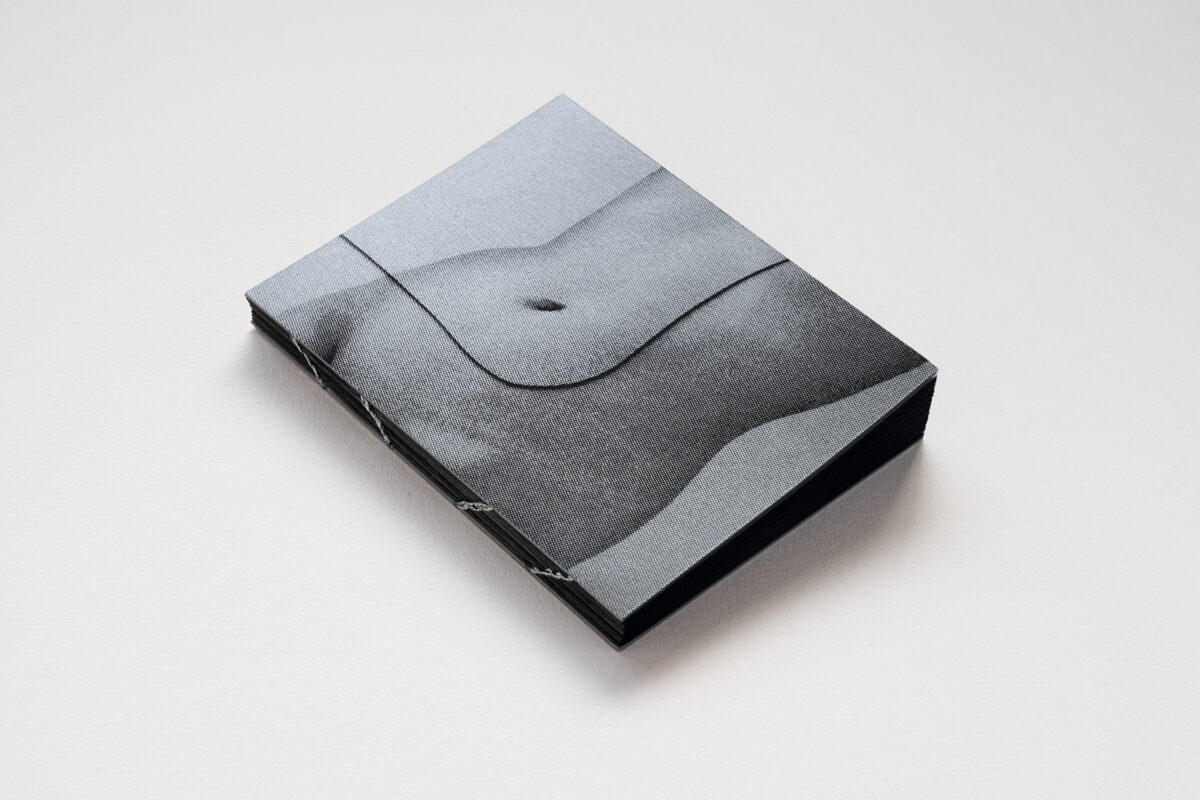

Sayuri Ichida’s Absentee is a book that feels. It functions as the sum of its parts, building a tense atmosphere as it goes. In many ways, it is a collection of separate photoshoots and experiments with different ways of approaching the ideas Ichida is trying to express, brought together through a binding reminiscent of Kikuji Kawada’s The Map (1965), with multiple gatefold spreads that house their own four-image sequences. Whilst the metallic ink and black-and-white inversion gives her work an aesthetic consistency, and whilst comparisons to contemporaries can be drawn, the variety of approaches produces arresting images, both alone and in sets. The result, for me, is a book that respects images for what they are, rather than for what they can be used to signify or gesture toward.

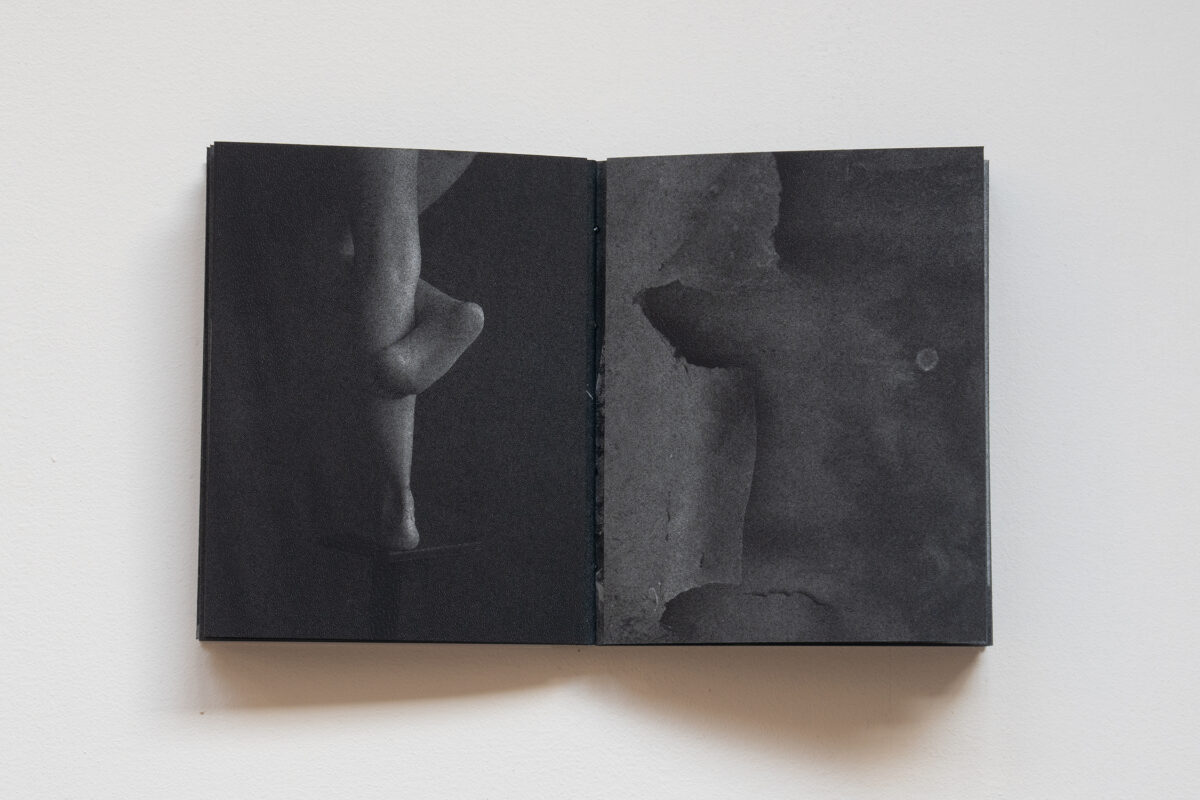

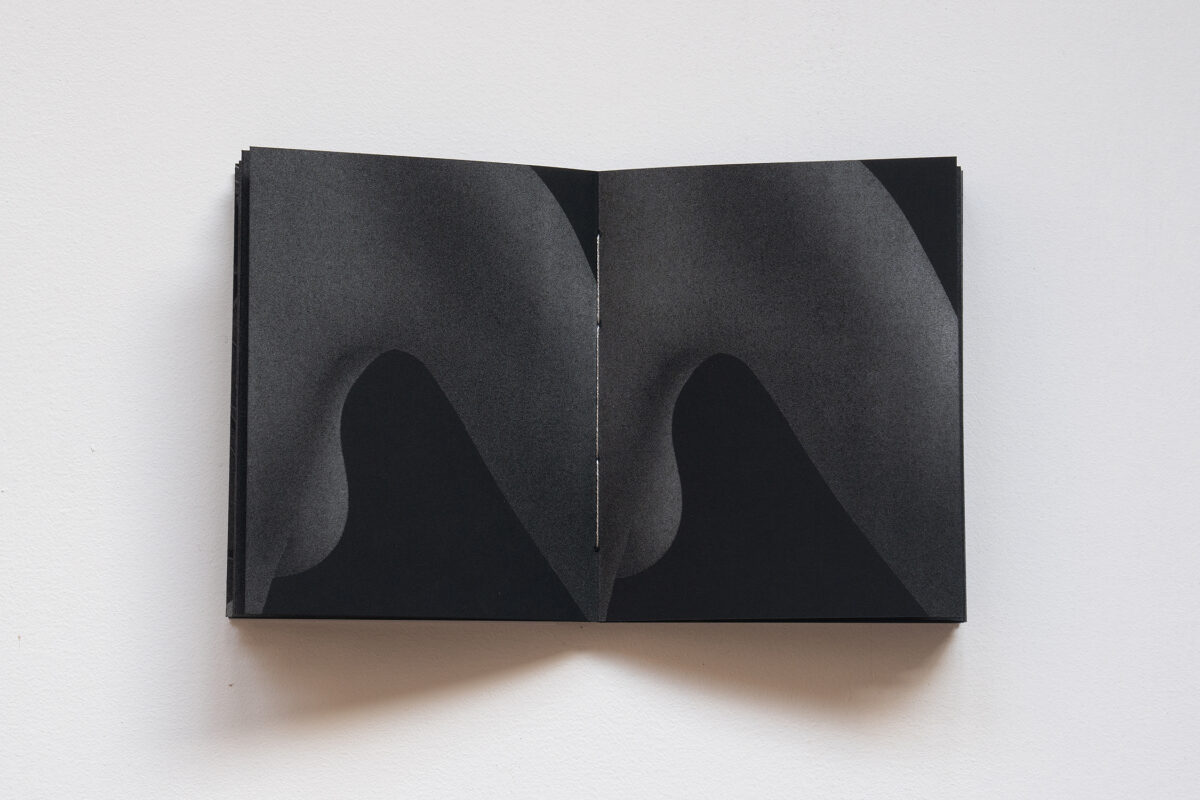

Looking through the book, an overarching feeling that many of Ichida’s groupings of images impart is that of the body being abstracted; more thing than person. Rather than a given pose or closeup of a body part being gestural and working as an expression of the artist’s self – as is typical of many such bodies of work – parts of this book instead affect a powerful sense that, just as the body dies and becomes lifeless, so too is the flesh made flat and empty when captured in an image. The feeling of detachment from the being one sees in a portrait of oneself, running parallel with an apprehension towards one’s forthcoming end.

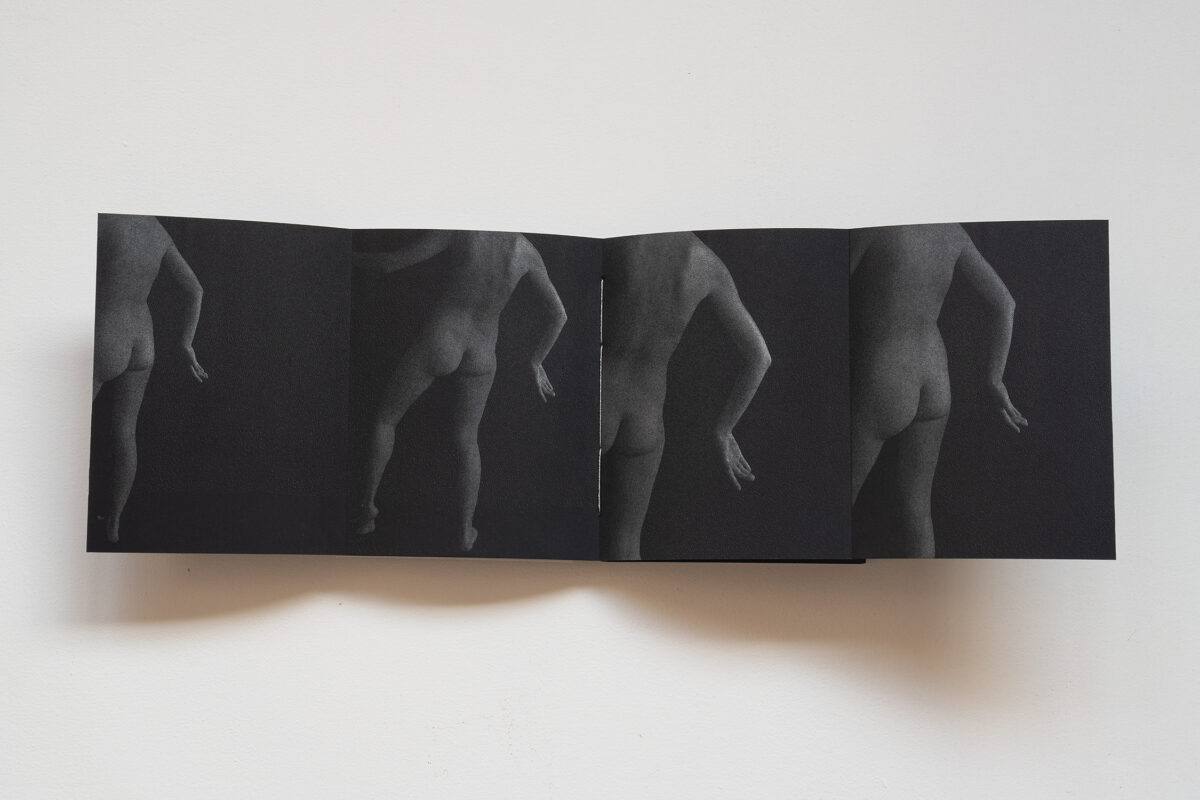

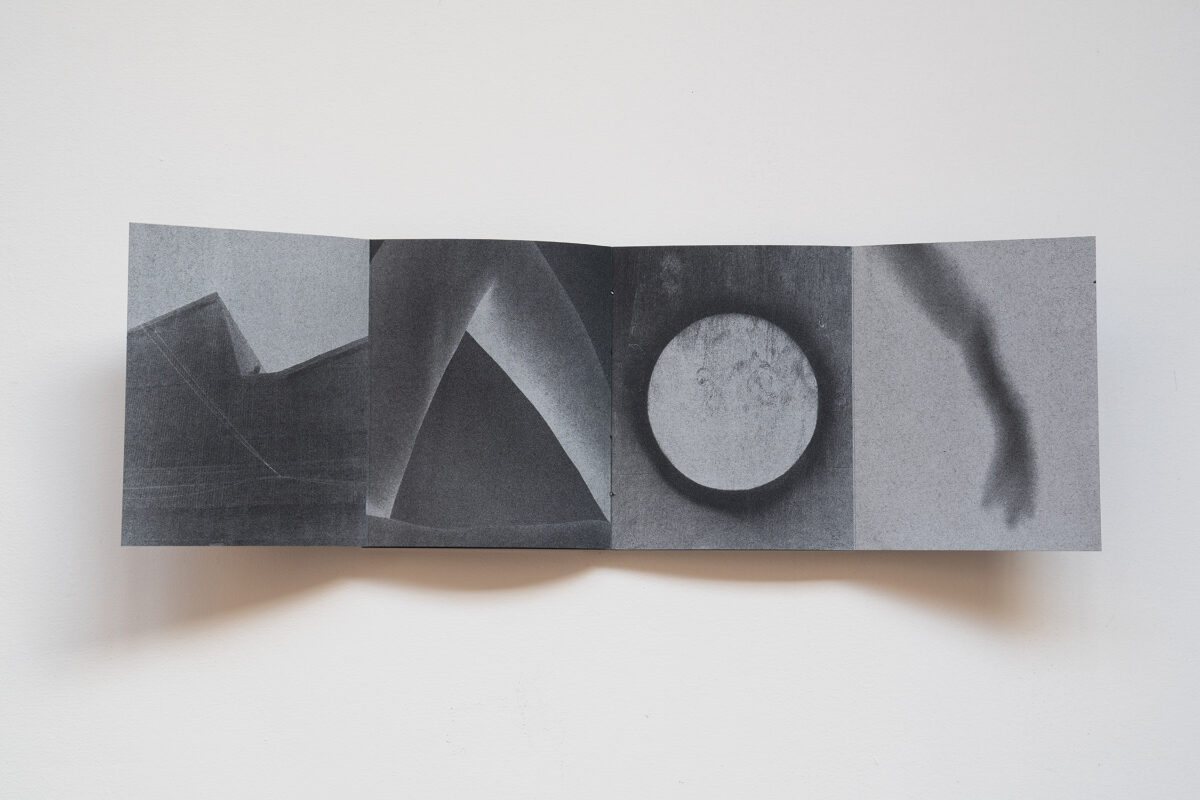

The gatefold presentation adds significant weight to this book. The outside pair of photographs – those we see before the gatefold is opened up – are typically duplicates or very similar in form; the image on the right page is often merely a reprint of the left, but copied, flipped or rotated. Elsewhere, especially within the four images constituting the inside of these foldout pages, such portraiture is set among highly sculptural images of cracked concrete, anonymous buildings, clouds and drawn curtains. The body seems here to be reduced to shapes and forms, lumps of flesh raw and exposed (we see no clothes; if ever the body were to be described as “vulnerable”, it would be here, where every instance of it is either hiding or obscured). The scenes of the external world, broken, decrepit and lifeless as they are, feel to me like a mirror to the internal world of Absentee’s faceless models.

What are evidently inverted studio shots of a model standing on tiptoes and with dangled arms begin to feel more convincing as some kind of corpse in a body of water, an empty vessel afloat in a great nothingness. Moreover, these close-ups of limbs being shot with flash prompt just enough of an association with that of the mortician’s documentation to carry the feeling of anticipation, the feeling of dread that spans throughout Absentee. After all, an absentee is one who should be present, but who is not.

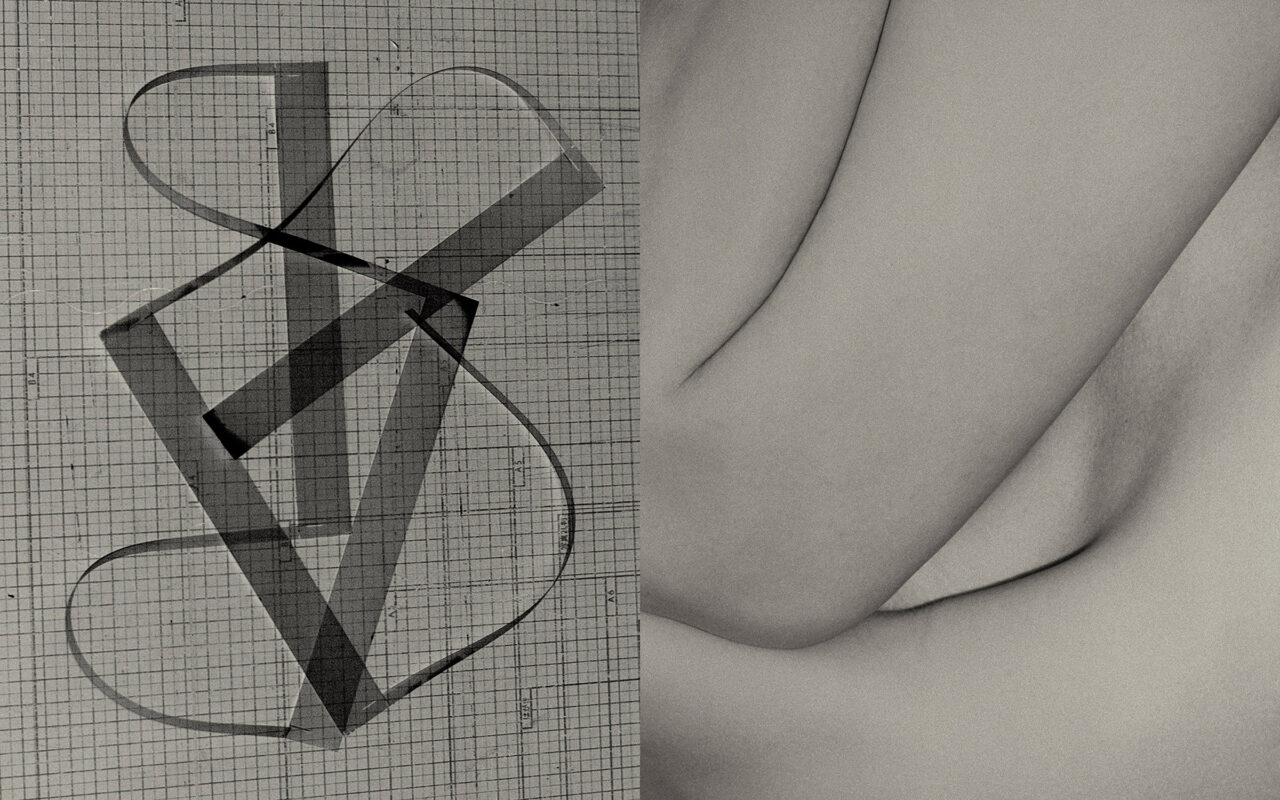

As a whole, Ichida’s foldouts can be enjoyed as sequences as much as patterns or ‘rhythms’ of photographs. Roughly halfway through the book, the arch of a leg is printed to the right of the peaked roof of a building. Proximate images such as these can be taken on a symbolic or comparative level, so as to say: “this is like this”, owing to the inverted V-shape of both the building and the leg, but they carry this intuitively, and in a more image-dense context than a typical two-page book. Rather than being reduced to pairs and propositions, Ichida’s gatefolds can be opened and closed in a few different ways, allowing the inside/outside to work in more ways than one.

Whilst Ichida’s work can be given attention for its use of medium-centric presentation, from the negative inversions and silver ink reminiscent of old film negatives, to the aforementioned repetition and flipping, on its own this is really the least interesting and least affecting part of the work. Those aspects contribute positively to the way this book feels as a whole, but not because, as meta-photographic elements, they are technically or conceptually clever. The images don’t work as references that point me to photography as the main subject, but ultimately point me back to a physical body – in this case presumably the artist’s – and a distress towards representation. This overwhelming feeling of anxiety about the body slowly becoming something flat, something still and unmoving, a corpse-like thing remains the central feeling conveyed.

Student work exploring questions of identity, expression of the self and of the body typically draws on a relatively consistent set of gestures and visual codes, often carried out more with reference to how such themes have been articulated by historical photographers – such as Francesca Woodman or Anne Brigman, or more broadly those images seen in mass circulation at the time – than to the ideas and experiences the photographer actually wishes to convey. Many bodies of work engaging with the male gaze, for example, seem too often to reinforce its visual logics in spite of the artist’s statement’s claims to the contrary. Self-imposed standards of beauty and the domination of certain visual tropes can sometimes influence work to the point that, in both cases, it engages in dialogue with other images more than with those who view them – and even those who make them. In such a case, the artist’s conception of their “self” merely constitutes a programmatic series of references.

Some of the gestures in Absentee do look familiar, and a reader might be forgiven for thinking that elements of the work feel slightly ‘derived’ from others, or even that it is a very ‘studied’ work; certainly, Ichida could be taken as wearing her influences on her sleeve. The difference for me, however, is that Ichida’s work embraces the discomfort and apprehension described above, as well as enjoying visual ambiguity rather than aiming for hard-coded messages. The figures in this book could even be ourselves: Ichida embraces anonymity, to the point that “the self” feels deliberately excluded by these gatefolds that cut into the models’ faces – we can see that these figures are a person, but as an image, they feel alienated and distant.

What is so often lost by work with conceptual aspirations is a love of looking at images. Taken as a whole, however, Ichida clearly understands that the viewer is the one taking these images in, and because of that focus on images and their affective strength, Absentee gives me moments both profound and often visually powerful.♦

Images courtesy the artist © Sayuri Ichida

Absentee is a self-published artist book handmade by Sayuri Ichida, in an edition of 50 copies. It was designed by Tomasz Laczny and launched in November 2021.

—

Callum Beaney is a photographer and writer based in the UK. He is co-editor of C4 Journal, a platform focused on photobooks.