Top 10

Photobooks of 2023

Selected by Alessandro Merola

As the year draws to a close, an annual tribute to some of the exceptional photobook releases of 2023 – selected by Assistant Editor, Alessandro Merola.

1. Masahisa Fukase, Private Scenes

Prestel

Obsession is carried out to the limits in both content and production in Prestel’s enthralling entry into Masahisa Fukase’s archive. Again, we find that the art the Japanese photographer produced towards the tail-end of his working life bears an intense and burning experimentalism that surpasses even his greatest opus. Private Scenes is off the charts brilliant, with its wild and enticing cover, glossy black pages and cinematic format through which we enter Fukase’s inner-theatre. It brings together “Letters from Journeys” – consisting mostly of Fukase’s street “selfies” taken across Europe and India in 1989 – and the more sprawling “Private Scenes ’92”. Uninhibitedly brush-stroked with colourful inks, the latter offers an amped-up and fevered tenor to Fukase’s mundane, sometimes surreal, street scenes. Each feels world-containing, condensing elements of documentary, performance and autobiography, with the artist an ever-lurking, unresolvable shadow-presence. Not only does this title contribute new insights into Fukase’s eccentric ways of seeing, but adds a new dimension to his boundary-pushing ideas around subject and object. Indeed, few artists have so ingeniously lent expression to the medium-old cliché that you photograph yourself in the other.

2. Chloé Jafé, SAKASA

the(M) éditions and IBASHO

Up until now, the books which make up Chloé Jafé’s trilogy have only been available in pricy limited editions, so this trade release is very much welcomed, not least for the fact it will, in turn, broaden the audience for, and appreciation of, this most creative and tenacious documentary photographer. SAKASA – which appropriately translates to ‘upside down’ – consists of three extremely elegant titles in which Jafé narrates her experiences across the Japanese archipelago, photographing, respectively, the women of Yakuza, the shadows of Okinawa and the fallen of Osaka. Housed within a stunning slipcase embossed by a black dragon, they stand shoulder to shoulder as technically accomplished and ambitious works. Through a mix of photography, hand-written notes, diary entries and ephemera, Jafé seamlessly stitches together underworlds, but in a way that is ambiguous and incomplete, implying events which unfold between the pages. Continuously feeling out the fine line between outsider and interloper, Jafé situates collaboration at the centre of her practice, seeking to stimulate and interweave the contributions of her subjects to constitute a common narrative. Jafé was clearly always in it for the long haul, so it is fitting that the(M) éditions and IBASHO have taken no shortcuts in their production of her very special project.

3. Tommaso Protti, Terra Vermelha

Void

The opening of Tommaso Protti’s remarkable book, Terra Vermelha, invokes a sense of saudade, depicting dystopic scenes from the end of the world. This is the Brazilian Amazon today, where indigenous communities are fighting for survival in the face of rampant deforestation. What follows is a dense, disorientating and elliptical reportage that riddles through a conflict-stricken hinterland, unravelling – in the dead of night – stories about savage land-grabs, forest fires and brutal gang murders. Humanitarian crises intersect and confound; forthright and full-bleed, Protti’s photographs demand our undivided attention in order that we can even begin to understand what we are looking at, not to mention what is at stake. The book culminates with a reflexive reference to the photojournalistic thrust of Protti’s practice, with mocked-up newspaper clippings collaged to captivating effect. Lending context to his otherwise captionless photographs, they bring home the harrowing realities and wrought complexities of the rainforest. Needless to say, few publishers could have taken us into the Amazon’s heart of chaos as nightmarishly as Void have.

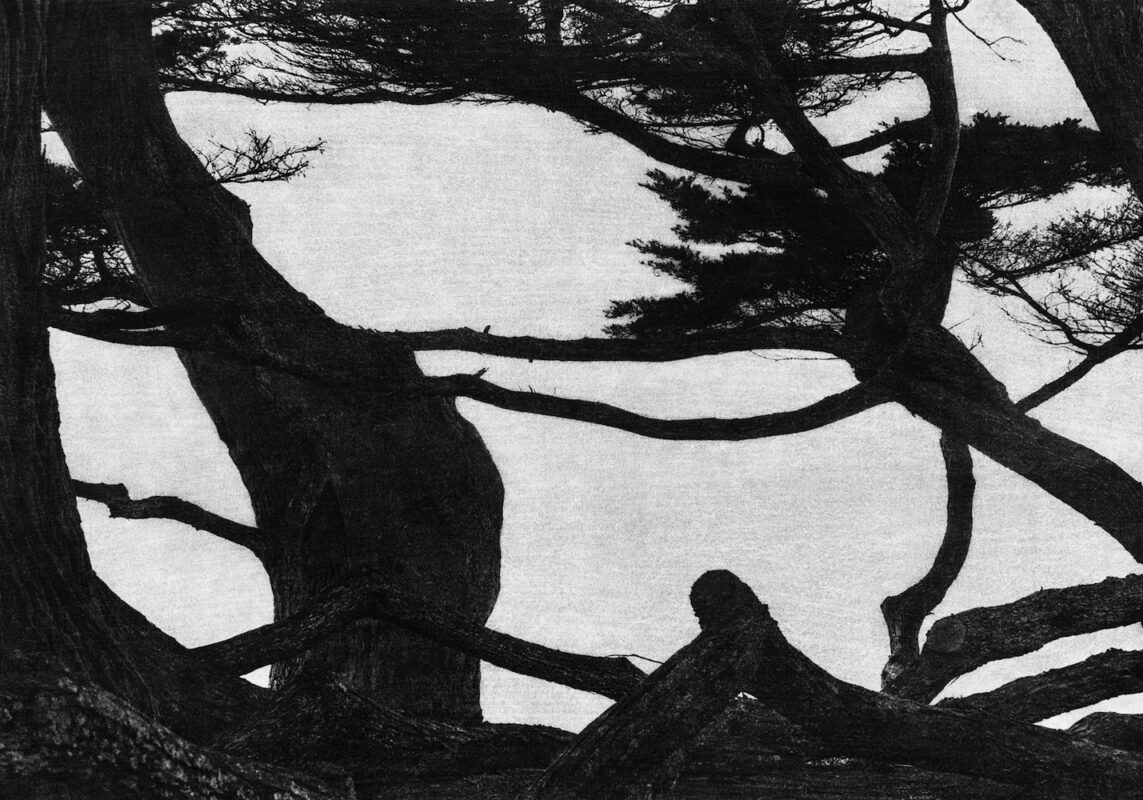

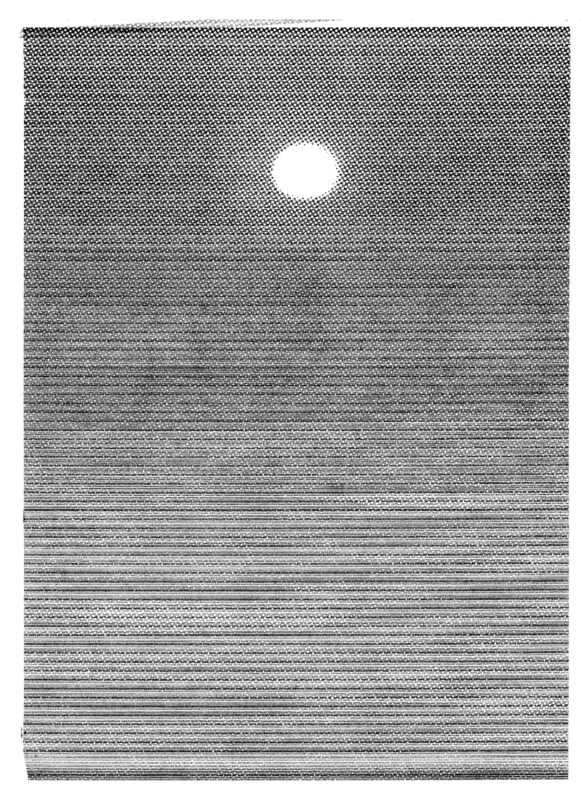

4. Jungjin Lee, Voice

Nazraeli Press

Jungjin Lee’s sublime, immersive and utterly hypnotic entry begins with Pablo Neruda’s ‘La poesía’, in which the poet recalls the night his craft called out to him, amongst raging fires, without a face. This epiphanic image propels Voice, which is, at its core, a meditation on making, resolving and speaking to things. Lee has divided her large-scale book into four stanza-like sections which are punctuated by black spreads. Whilst each is not easily thematised, throughout one finds the alliteration of forms, which spin out stories of the desert – as concept and idea. This is not the first time Nazraeli Press have done exacting justice to the lush materiality of Lee’s photographs, rendered here in quadratones. Collectively, they absent themselves from context; unburdened by identifiable landscapes or linear narrative, they are beholden to no time or place but their own. And even where there is emptiness – stretching sands and lost horizons — there are storms of grain, of noise. Herein lies this book’s transcendent power: transforming landscapes and photographic effects into an aural, bodily and spiritual experience which pierces us with infinite emotional textures, and voices.

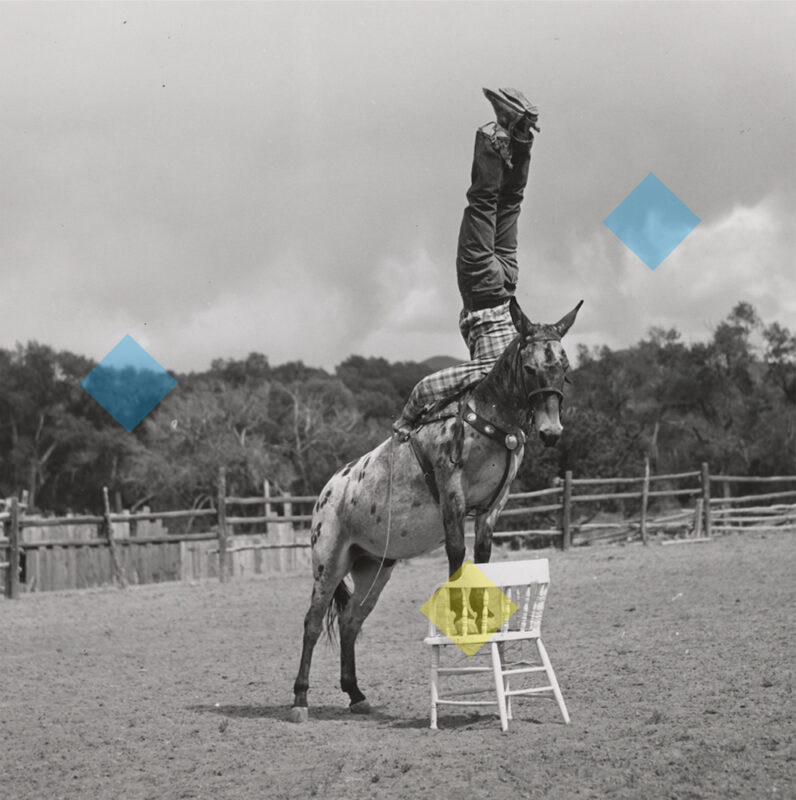

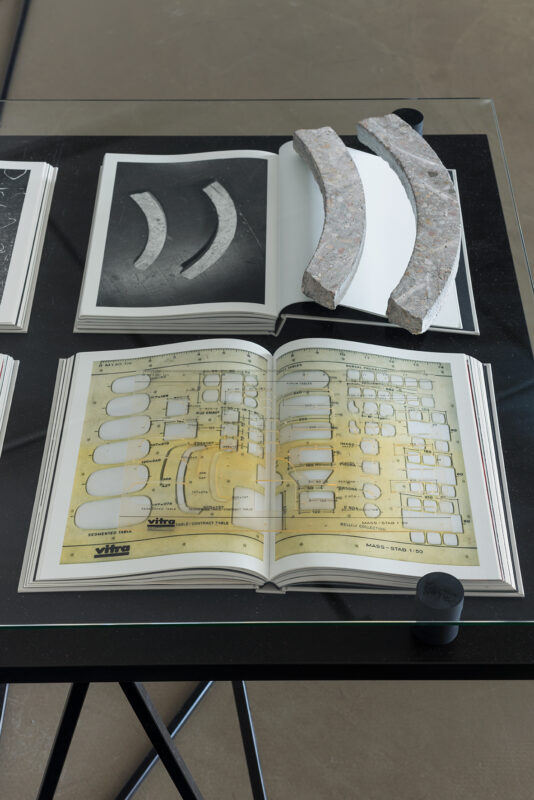

5. Robert Cumming, Very Pictorial Conceptual Art

Stanley/Barker

Out with Stanley/Barker, Very Pictorial Conceptual Art is both enlightened and enlightening, building significantly on Aperture’s earlier entry into the astonishing archive of Robert Cumming. The body of work the late American artist produced in the 1970s – the decade he settled on, and began his serious engagement with, photography – has been savvily composed by editor David Campany, whose essay makes the convincing case for Cumming’s range and daring experimentation with the medium that was well ahead of its time. Repetition is employed throughout this handsome book, with its gatefolds filled with multiple views of the same subject-objects, revealing the unique ways Cumming looked, thought and sketched with his large-format camera. Entered swiftly together, one finds that you can always stumble upon something new or intriguing, even if Cumming’s camera models, motorised shark or “0 + 0 = 0” donut equation deliberately defy any utilitarian function. Whether these are images of elements of sculpture or the artist’s idea of sculpture might be beside the point. Let us revel in the incisive eye of Cumming the beholder.

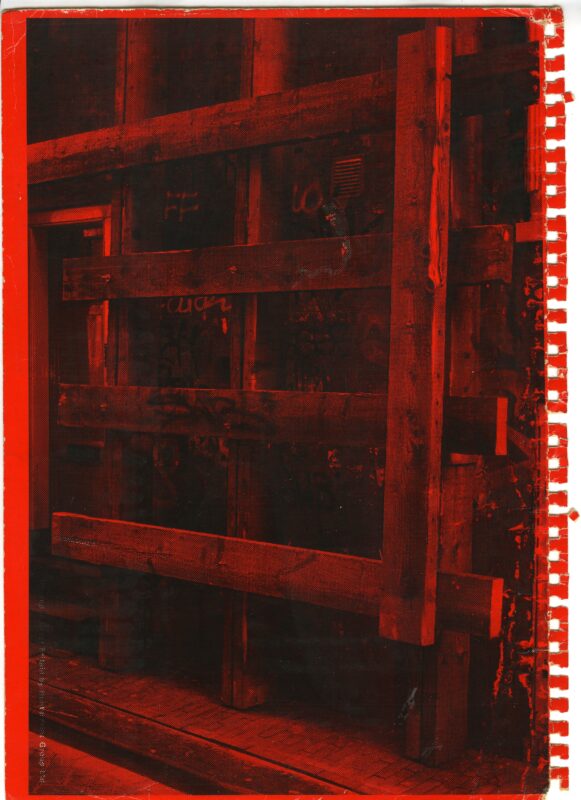

6. Ruben Lundgren, Dream Machine

Jiazazhi

This marvellous and amusing album tells the story of China’s craving for the new through a very specific sub-genre of 20th century studio portrait photography. As testified by Ruben Lungdren’s Dream Machine – and contra to popular assumptions – ordinary Chinese folk up and down the country embraced “exotic” commodities, including the automobiles and aeroplanes – or gas-guzzling “fart-carts” – that appear in these pictures as kitschy cardboard cut-outs. One can only imagine how painstaking Lungren’s research was in order to source these gems, which fundamentally speak to the power of seeing as not only dreaming, but believing. Jiazazhi’s design is simply delightful, from the spiral-binding which lends a scrapbook feel to the windows which invoke the sensation of entering other worlds, new worlds. And, yet, the old world remains an ever-present too, with quaint visions of the banks of the West Lake embroidered on the cloth cover, details of which are scattered throughout the pages, reverberating in the imaginary. This is a book of rare quality; a real labour of love by Lundgren.

7. Bindi Vora, Mountain of Salt

Perimeter Editions

Another noteworthy vernacular contribution comes from Bindi Vora, whose lyrical pandemic piece winds up as a cacophonous reflection on recent times. Published by Perimeter Editions, Mountain of Salt is small but densely layered, containing hundreds of cleverly juxtaposed archival photographs in concert with appropriated buzz-phrases, idioms, jokes and pledges which the artist pulled from news articles, press conferences and social media in the wake of Brexit and the Black Lives Matter protests. The loose intercourse of text and image delivers a series of thought-provoking moments and emotional triggers, accumulatively resonating for the ways in which eras are formed and form us, both subconsciously and violently. Whilst the digitally overlaid shapes are light and subtle interventions, they do just enough to disturb the syntax of the images, making history peculiar and alive. Vora’s is one of those books that feels both specific and sweeping at the same time; her era-encapsulating vision of a spectred isle.

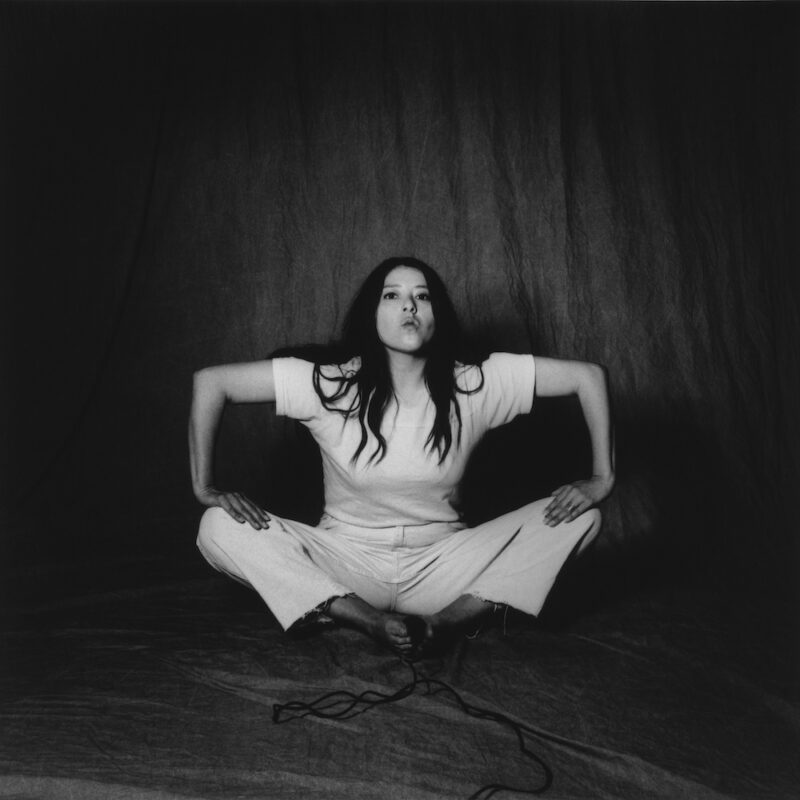

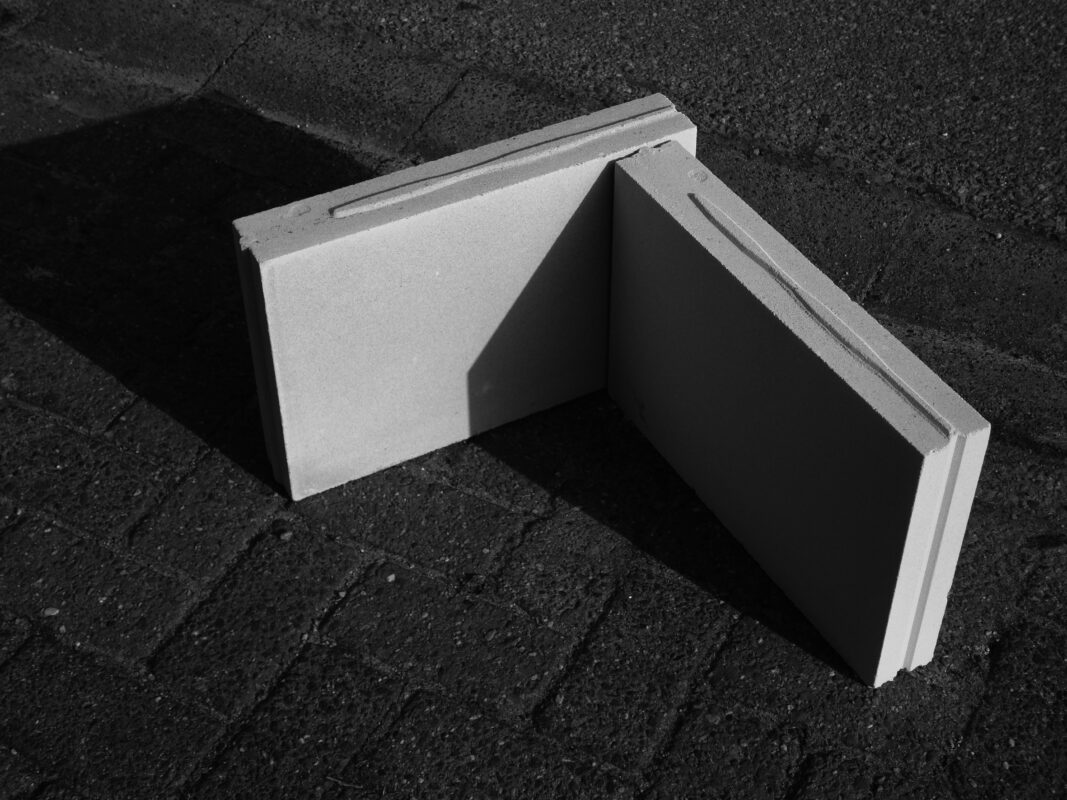

8. Tarrah Krajnak, RePose

Fw:Books

On making history alive, RePose, Tarrah Krajnak’s deft and deceptively powerful conceptual work with Fw:Books also deserves a mention. The title presents a typology of poses by women, (re)performed by the artist – on-site and in real-time – from her personal collection of printed matter, ranging from fashion catalogues and art history books to vintage pornographic magazines and anthropological studies, even if they are never indexed here. Whilst the female body in art has historically been mute and functioned almost exclusively as a mirror of masculine desire, Krajnak inhabits the body as a visual territory, to be both critiqued and claimed. These are not so much reappropriations of poses, but, rather, reoriginations of them, with Krajnak’s cable release serving as a kind of umbilical cord which connects her to other images, other women. Although this book is stripped-back and modest in its production, it nevertheless possesses an immediate aesthetic charge, conveying the flickering intensity of a flipbook. The pages unfold and map out a literal lineage, through which Krajnak dances like a ‘snaking aggregate’, as is articulated most beautifully in the accompanying essay by Justine Kurland, who is herself no stranger to archival animations.

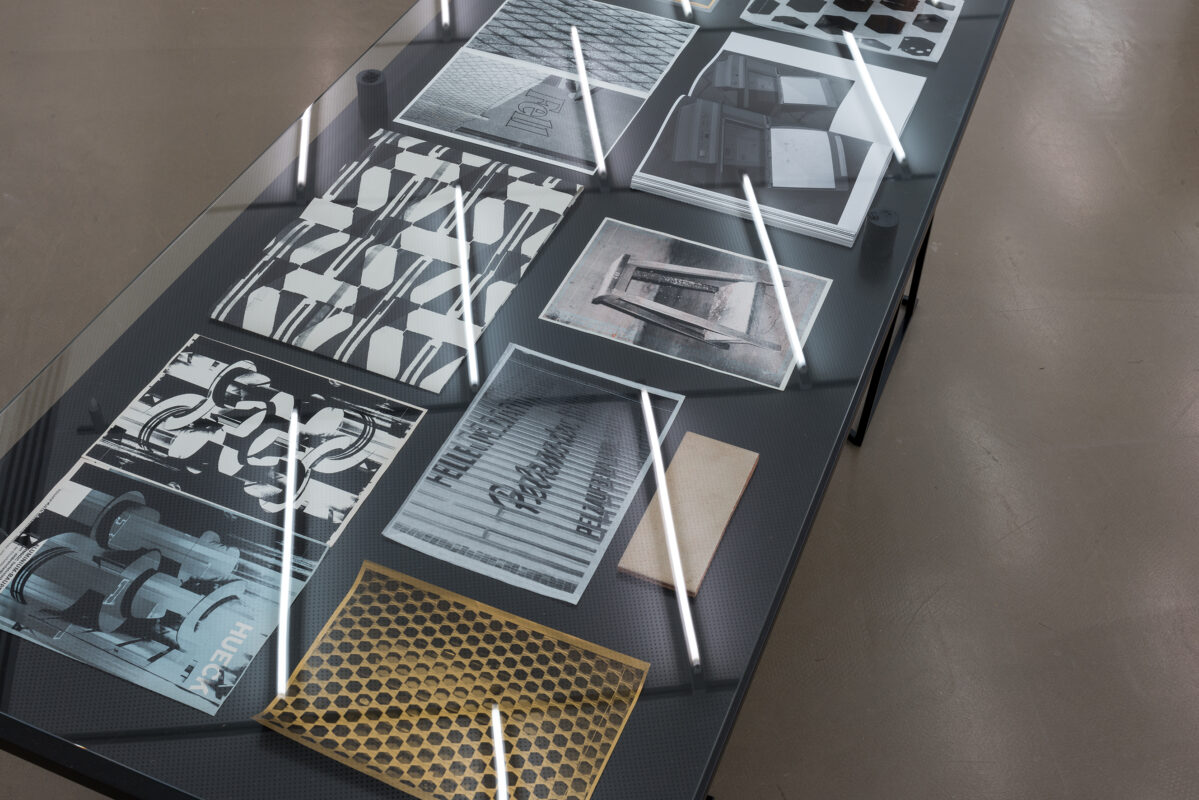

9. Corita Kent, Ordinary Things Will Be Signs for Us

J&L Books and Magic Hour Press

One of the great discoveries of the year has come courtesy of J&L Books and Magic Hour Press, who have, in Ordinary Things Will Be Signs for Us, condensed Corita Kent’s vast trove of source slides into a graphically bold and joyful book which offers a new context to the revolutionary screen prints for which the former nun is known. Immaculately reproduced by Jason Fulford with rounded corners and a real care for colour, the jam-packed visual combinations – laid out innovatively and unpredictably – have the sister singing her way through 1960s Los Angeles, from its vernacular surfaces – a bricolage of street signs, billboards and supermarket produce – to the classrooms of the covenant where Kent taught art. What is most commendable about the edit is how it does not impose a narrative on behalf of the artist, but, instead, channels the spirit of this multi-levelled visionary and her uncanny ability to find meaning in all things modern. Whilst Kent’s language of photography might not bear the explicitly world-changing mission of her language of Pop, what it does teach us, or remind us, is how we see things not as they are, but we are.

10. Lin Zhipeng, Skinny Wave

Same Paper

With each new book, Lin Zhipeng, the Chinese photographer who goes by the name of “223”, distinguishes himself as an increasingly important voice within contemporary photography, and his latest is certainly a leap forward in terms of sophistication and subtlety. Assembled from the small aide-mémoires Zhipeng has collected on the road over the past 20 years, Skinny Wave proposes a B-side to the pop seduction for which the photographer is most celebrated, yet nevertheless retains his trademark blend of classical serenity and ornamental playfulness. It is clear that for Zhipeng, where there is beauty, there is a picture: a blossomed flower, a boy paddling in a stream, a split fruit. Same Paper’s intelligent design does well to enhance the book’s haptic dimensions – not to mention its onion-like layers of meaning – with its scratch-marked cover (which is actually one of four), heavily saturated pages and expansive gatefolds, whose shifts in attention subconsciously seep us into the memories of Zhipeng. Here is an artist who calls for a quiet, contemplative moment with photography; an intimacy that can only be bestowed by a book.♦

—

Alessandro Merola is Assistant Editor at 1000 Words.

Images:

1-Cover of Masahisa Fukase, Private Scenes (Prestel, 2023). Courtesy of Prestel and Masahisa Fukase Archive.

2-From ‘Private Scenes ’92’ (1991–92) in Masahisa Fukase, Private Scenes (Prestel, 2023). Courtesy of Prestel and Masahisa Fukase Archives.

3-‘Jun with her kimono’ (2016) from Chloé Jafé, SAKASA (the(M) éditions and IBASHO, 2023). Courtesy of the artist, the(M) éditions and IBASHO.

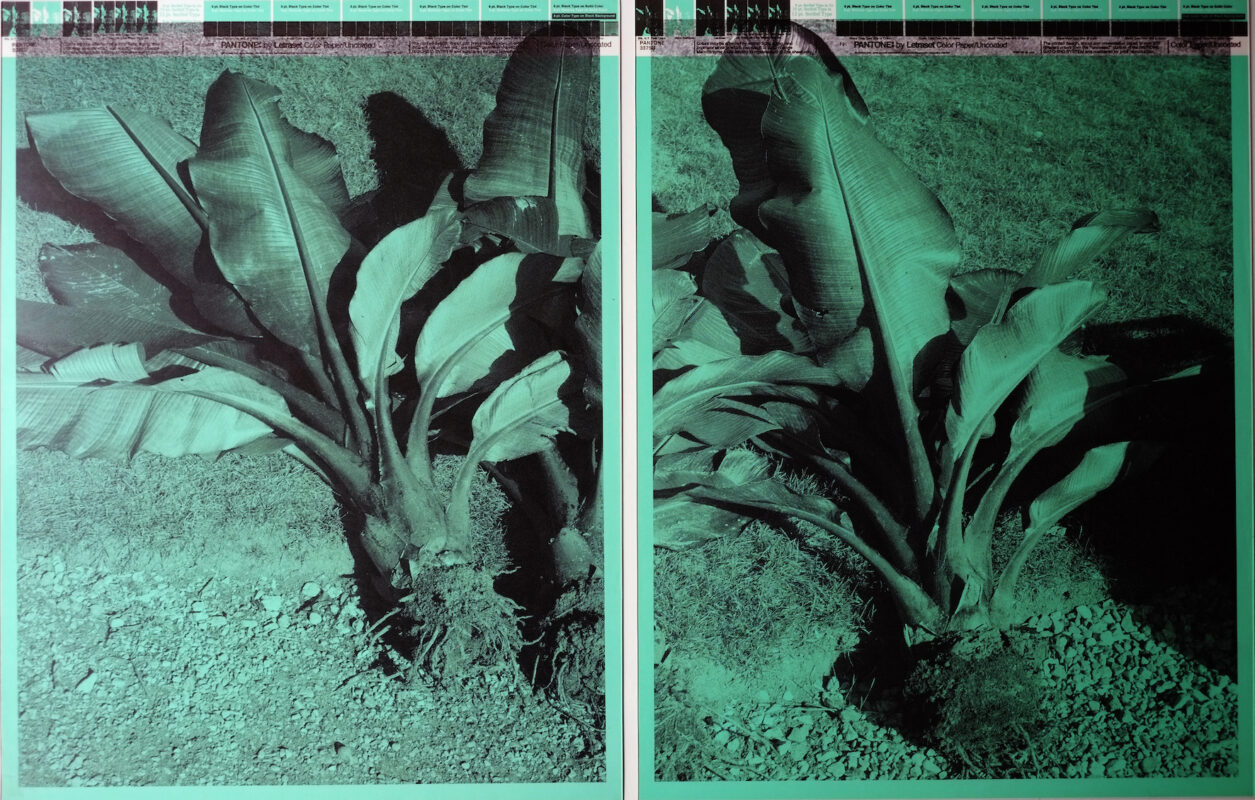

4-‘Manaus’ (2017) from Tommaso Protti, Terra Vermelha (Void, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and Void.

5-‘#29’ (2019) from Jungjin Lee, Voice (Nazraeli Press, 2023). Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery.

6-‘10 Unique Article A’s’ (1975) from Robert Cumming, Very Pictorial Conceptual Art (Stanley/Barker, 2023). Courtesy of The Robert Cumming Archive.

7-‘Untitled’ (c. 1980s) from Ruben Lundgren, Dream Machine (Jiazazhi, 2023). Courtesy of the author.

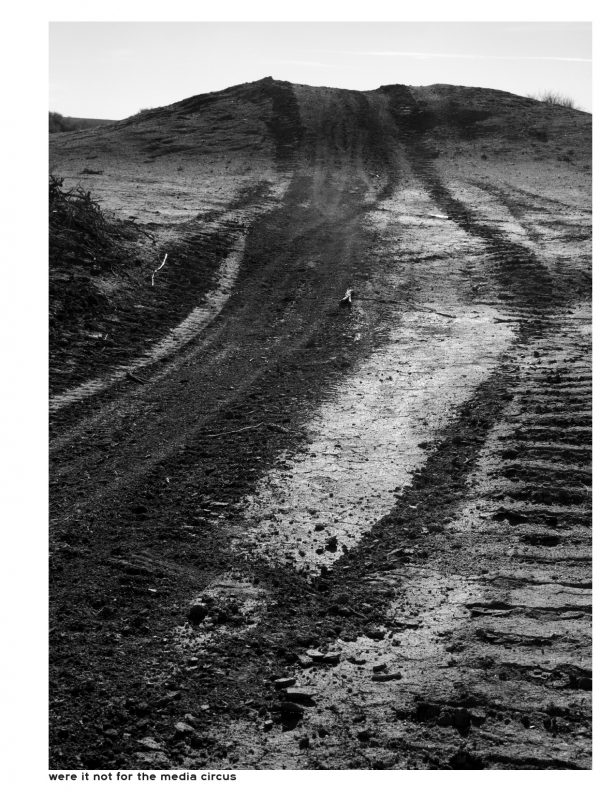

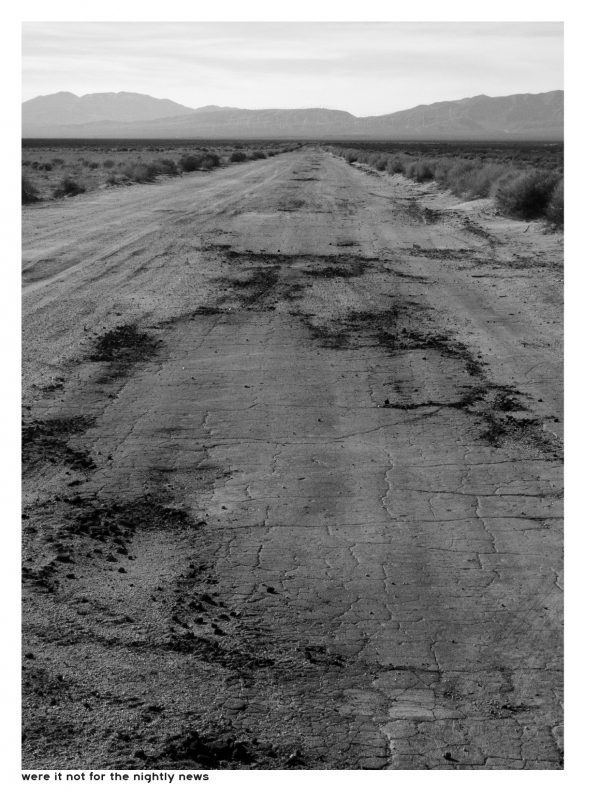

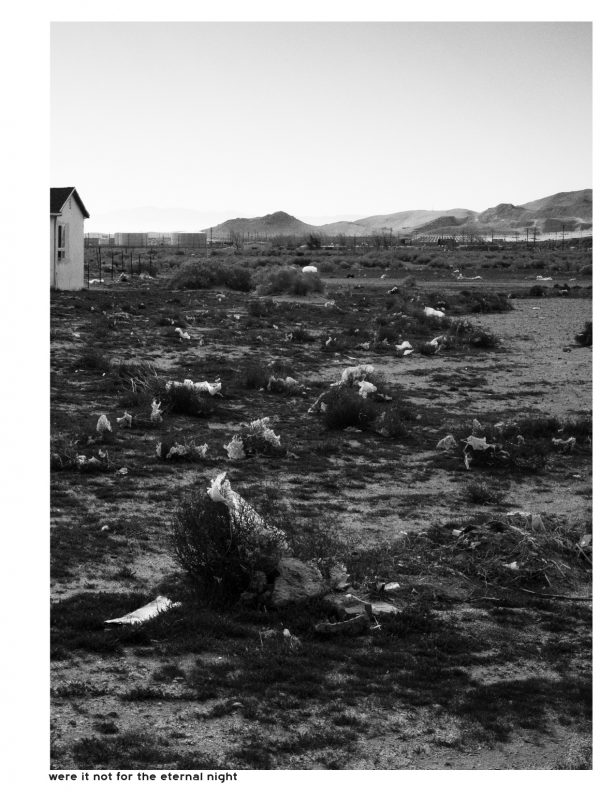

8-‘Quarantine is a stunt, they could be playing golf’ (2020–21) from Bindi Vora, Mountain of Salt (Perimeter Editions). Courtesy of the artist.

9-From Tarrah Krajnak, RePose (Fw:Books, 2023). Courtesy of the artist.

10-From Corita Kent, Ordinary Things Will Be Signs for Us (J&L Books and Magic Hour Press, 2023). Courtesy of Corita Art Center.

11-‘We have no purity in the night’ (2021) from Lin Zhipeng, Skinny Wave (Same Paper, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and Same Paper.