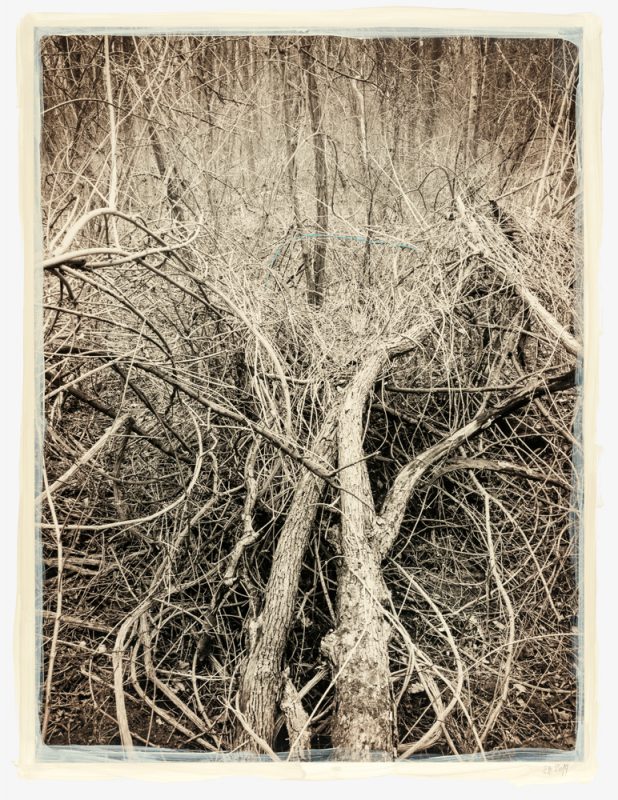

John Gossage

Looking Up Ben James – A Fable

Book review by Gerry Badger

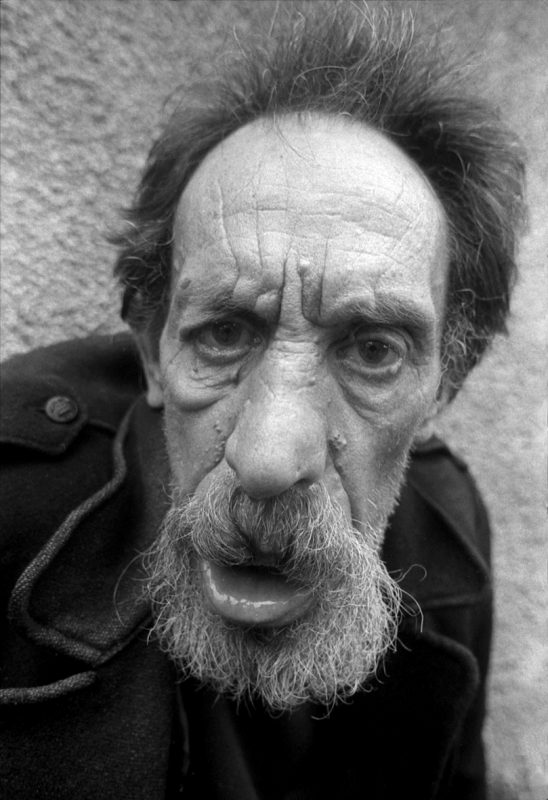

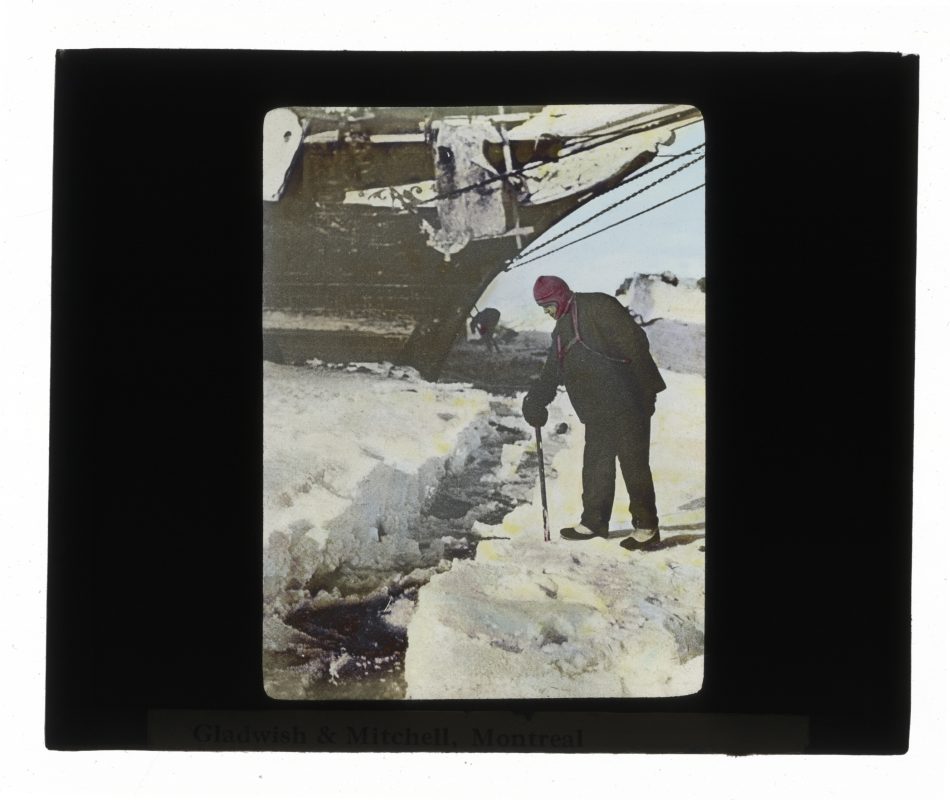

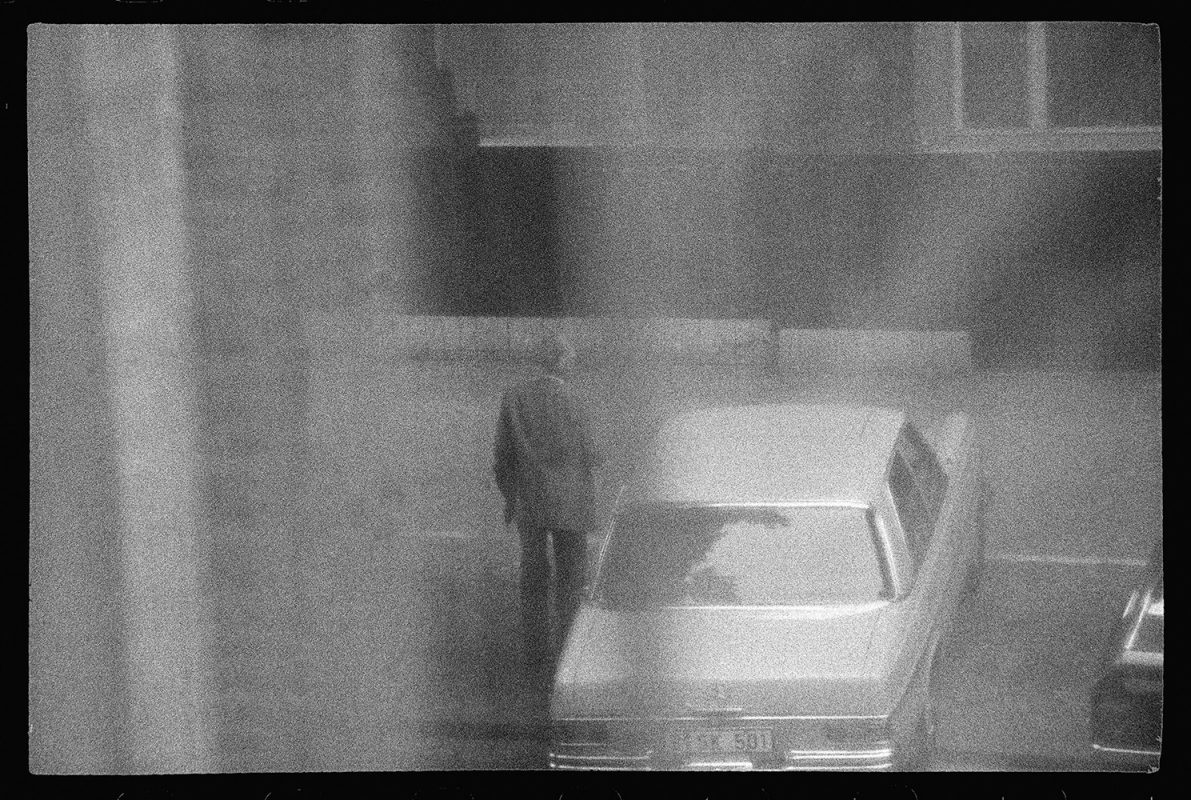

This is John Gossage’s ‘English’ book, although some of it was shot in Wales, and the title has Welsh connotations. Ben James was a Welsh miner photographed by Robert Frank when he came to Britain in the 1950s. Those British images prefigured the style of The Americans, and as an aside, I remember looking with Gossage for the location of another famous Frank picture, the London hearse, which was taken not in Belsize Crescent – as is sometimes alleged – but in Kentish Town, where I live. Alas, it had vanished during the rebuilding of a goodly portion of the area in the 1970s. What became of Ben James is also unknown, although in the book’s short text, Martin Parr imagines he and Gossage running into the miner’s descendants and being offered some Frank prints for £25 each.

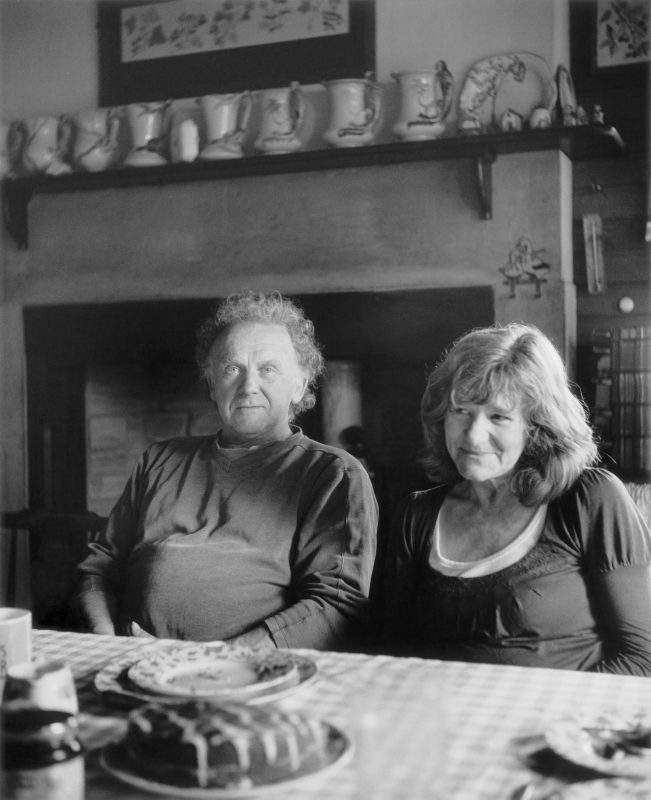

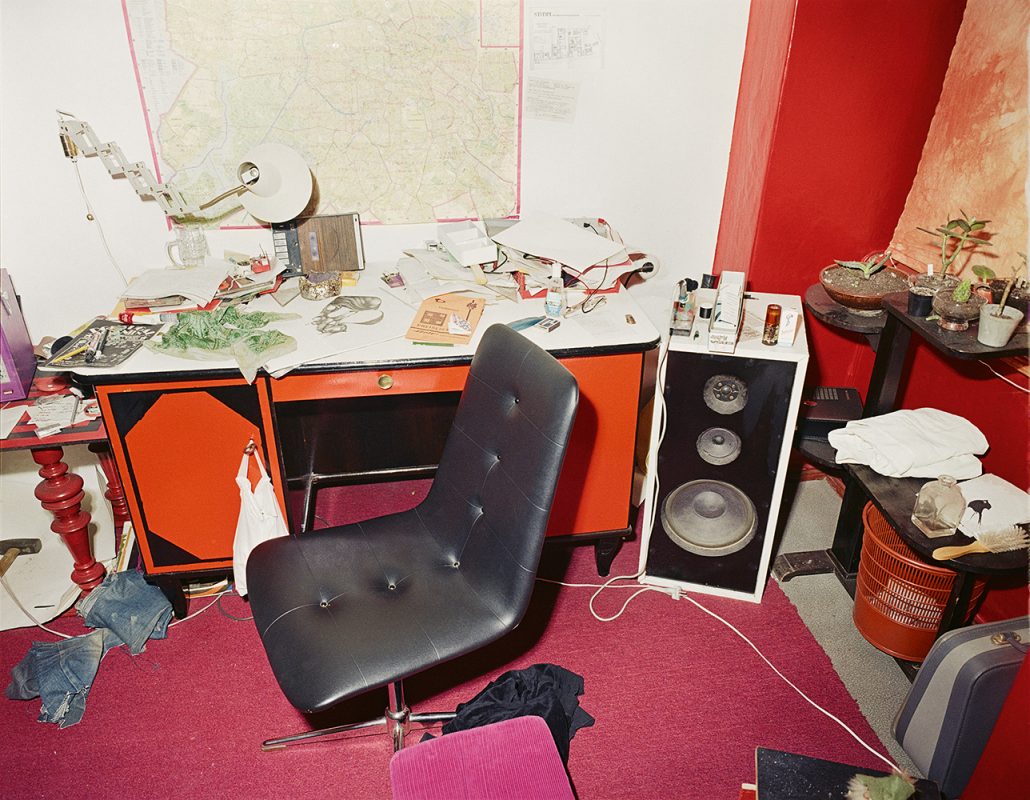

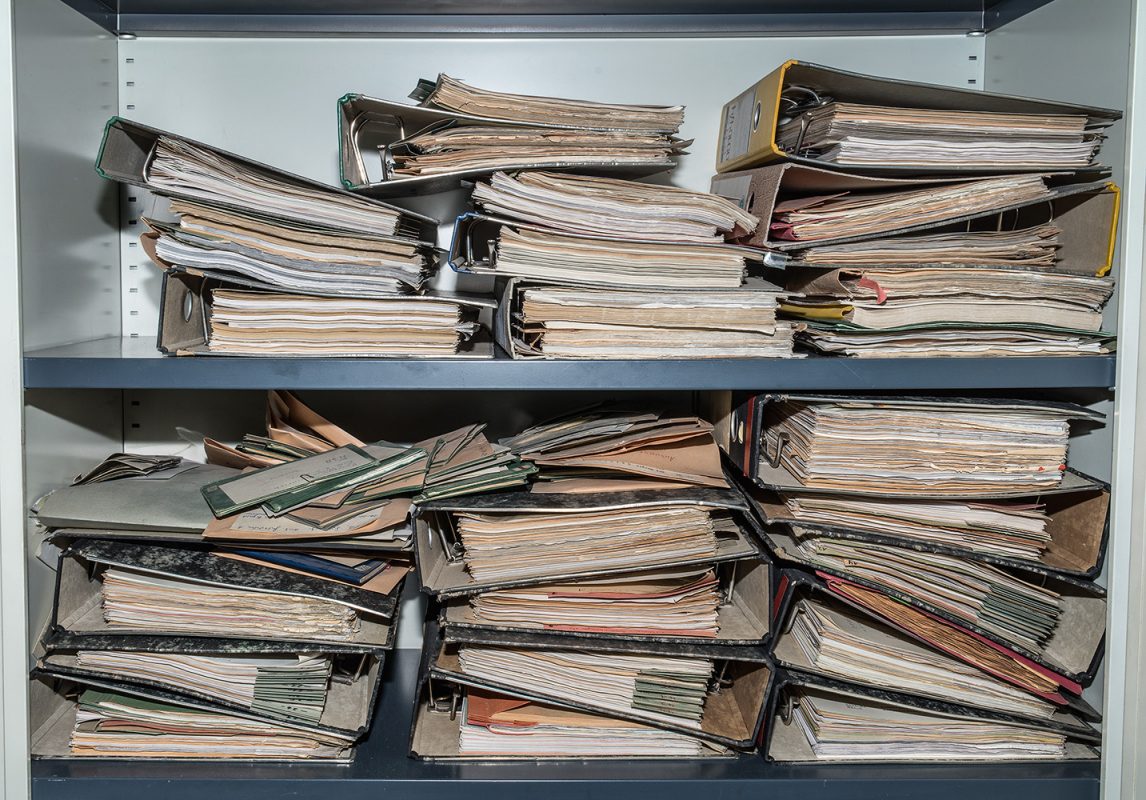

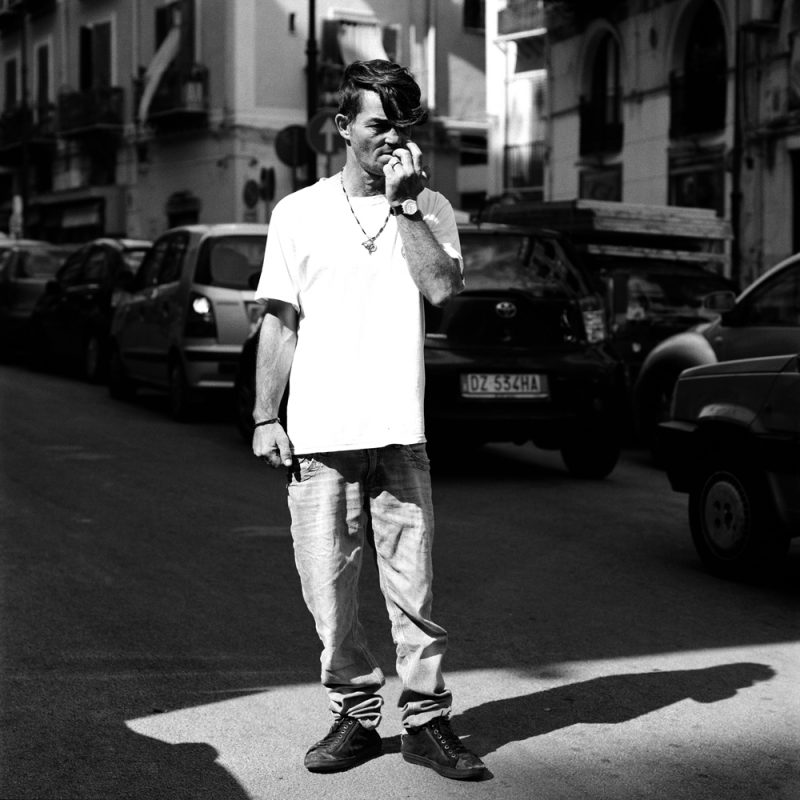

Gossage made the book when he visited Parr in Bristol in 2008 and the pair made a trip around the country, getting as far as Cumbria, where he made a splendid double portrait of photographer Graham Smith and his wife Joyce. This is a very personal trip, a visual travel diary. There are pictures of Martin, and Martin’s mother, and of his sadly departed dog, Ruby, familiar to the many visitors to his Bristol home. So this is firmly in the diaristic mode, an extremely popular, almost ubiquitous trope in contemporary photography. Some would say it is too popular, often coming into the ‘who gives a fuck’ category of so much social media culture. And it can frequently seem a little arch, a bit too knowing, especially when famous photographers photograph each other. There are odd references, for instance, to Martin’s well-known collecting habit, which might be regarded as an ‘in joke’, but Gossage always knows when not to push it. This is an exceptional photobook, for two reasons.

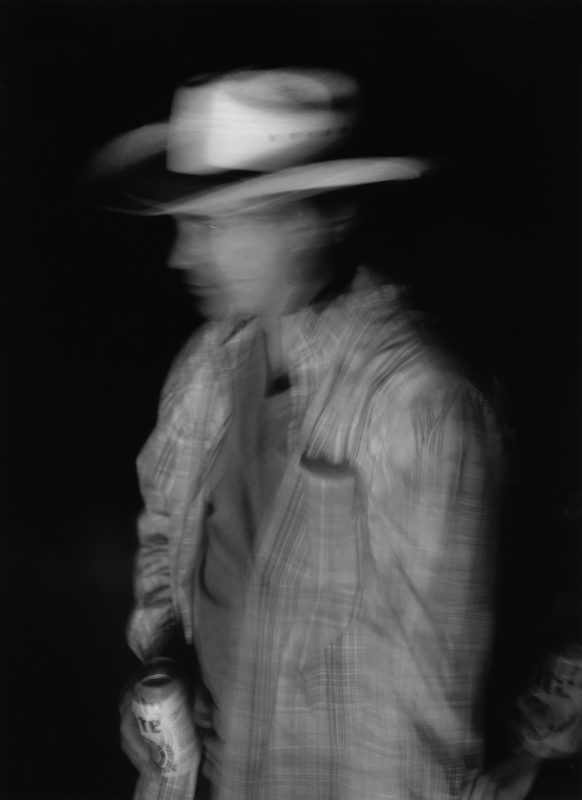

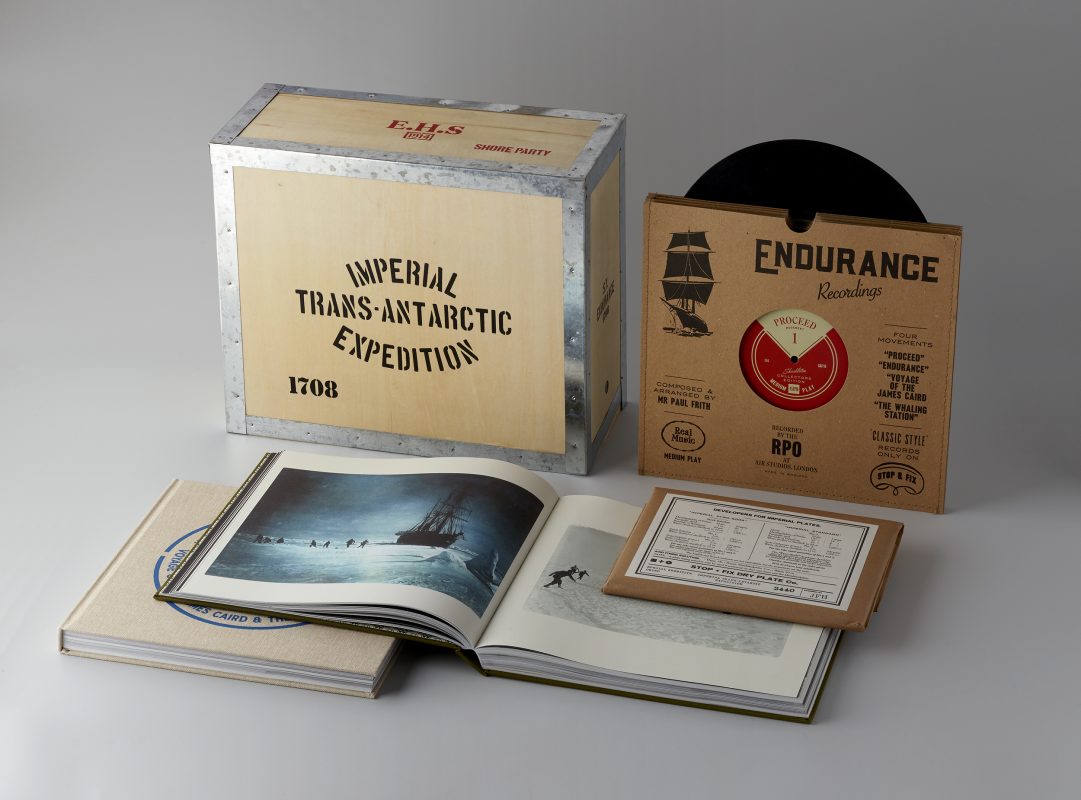

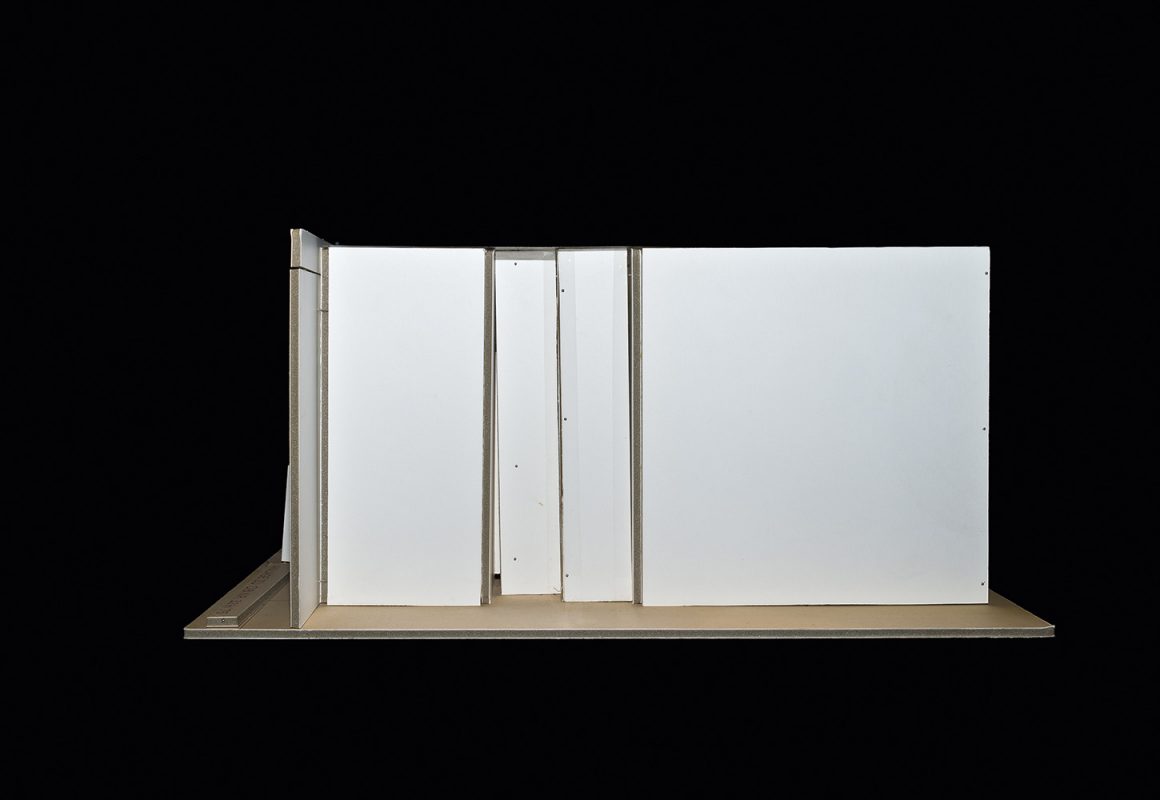

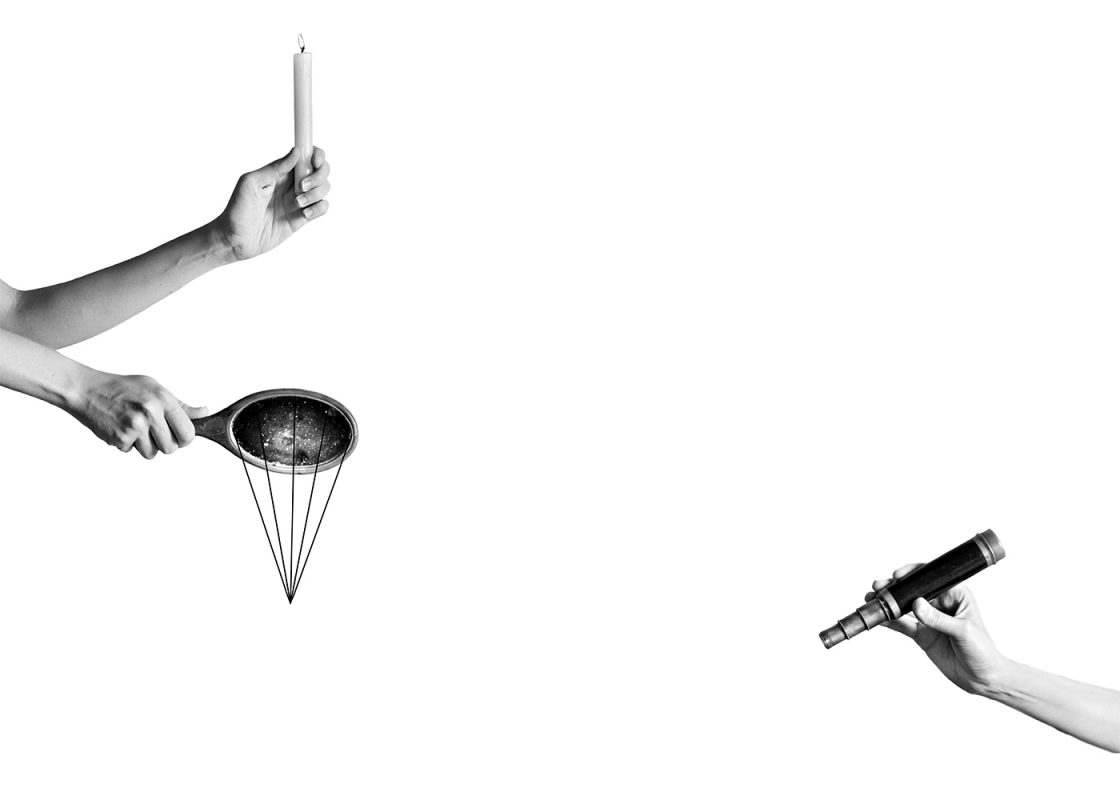

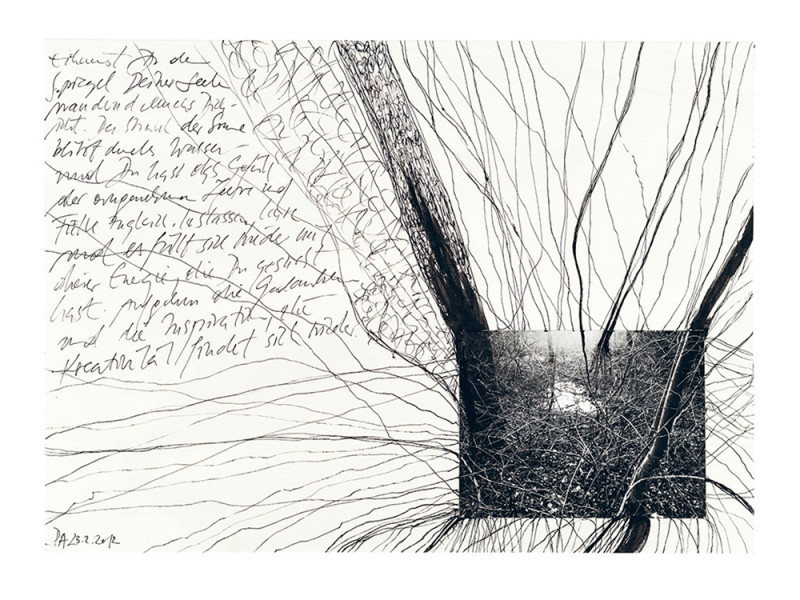

Firstly, the design and production. It is the finest that Steidl is capable of, with the master printer Gerhard Steidl challenged to produce sensuous black and white printing that equates to that silky gravure that was such a feature of photobooks in the 1950s and 60s. And the book is large, with a number of inserts in overlaid colour monochrome. The size, one might say, is antithetical to the intimate subject matter, but in this case it works.

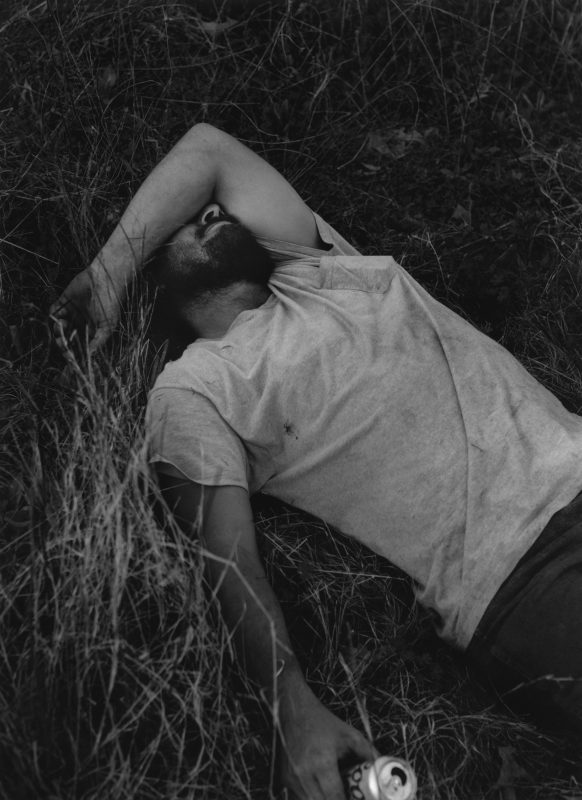

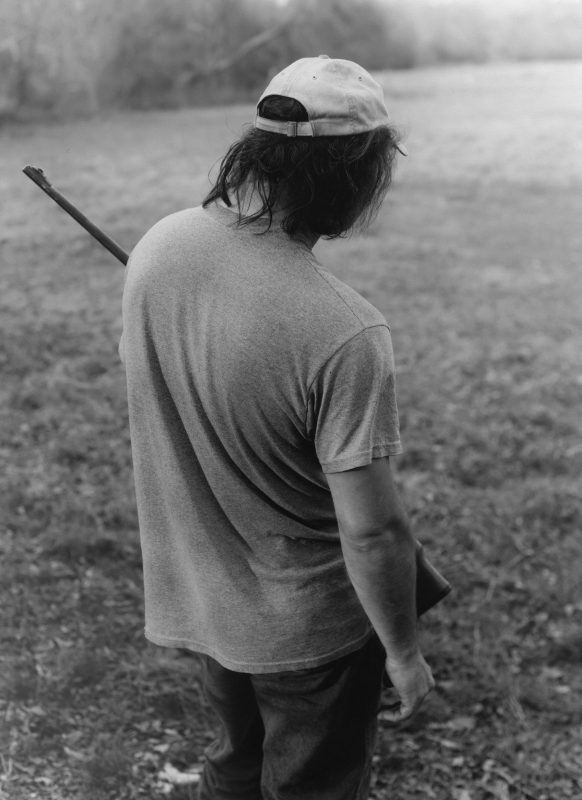

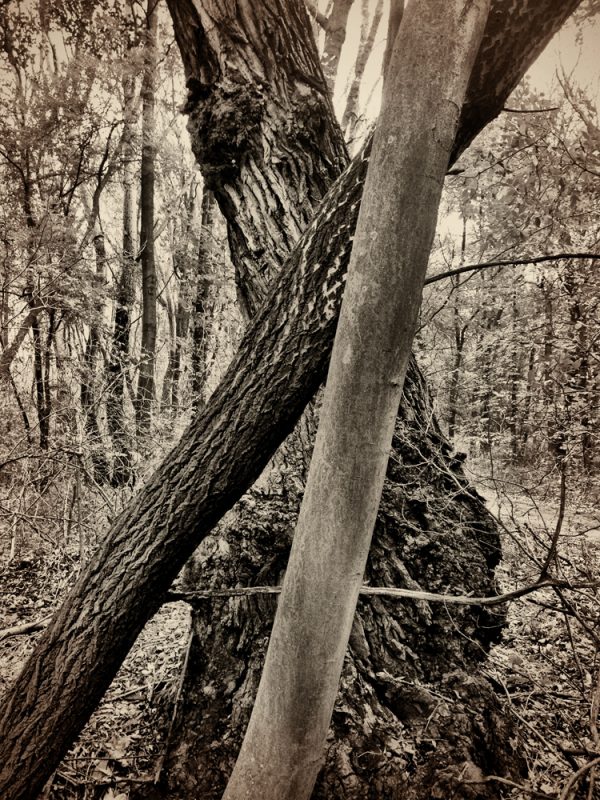

Second is the sheer quality of the images. Gossage has long said that the first criterion for a great photo book is great photographs. Too many, I believe, ignore this basic principle and imagine that complicated design and cute production results in a great photo book. More often than not it simply results in complicated design and cute production trying to inflate empty photographs. Not that design is ignored here, but it is not privileged at the expense of the photographs. Indeed, Gossage is also a qualified designer, and not adverse to pushing the envelope in both design and production terms. He likes the odd design twist – a small red point on an overlay picks out a flare spot in the picture beneath – but again, he has an innate sense of when to stop.

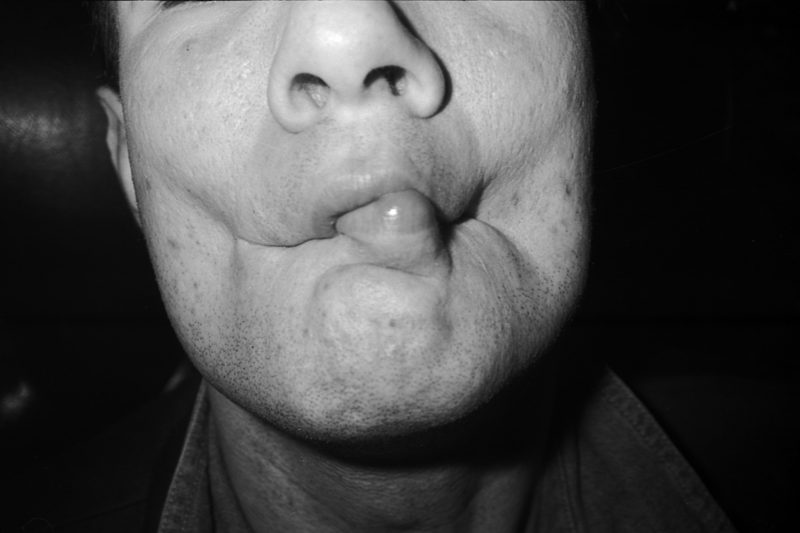

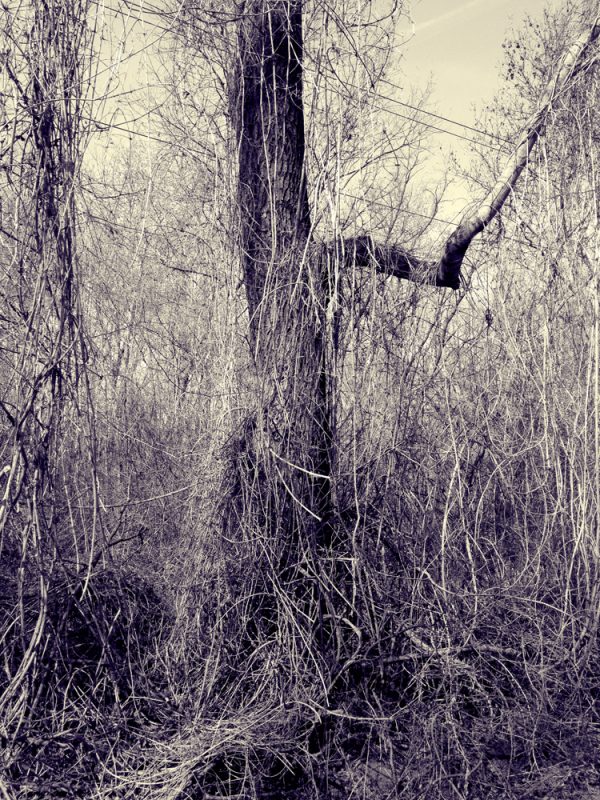

This is a book of photographs first and foremost, by an endlessly experimental photographer. He is essentially a street photographer, a flâneur with an emphasis upon the urban landscape, although that does not begin to describe the range or depth of his practice.

Gossage has developed into one of the most recognisable photographic voices over the years, and that can mean resorting – quite naturally, all artists do it – to a repertory of stylistic and contextual devices, that go to make up his distinctive voice. I know his work intimately, so I am very aware of his little strategies and visual foibles, but I can also say that, like a good jazz improviser, he is always trying to surprise himself, and come up with a picture that one has never quite seen before.

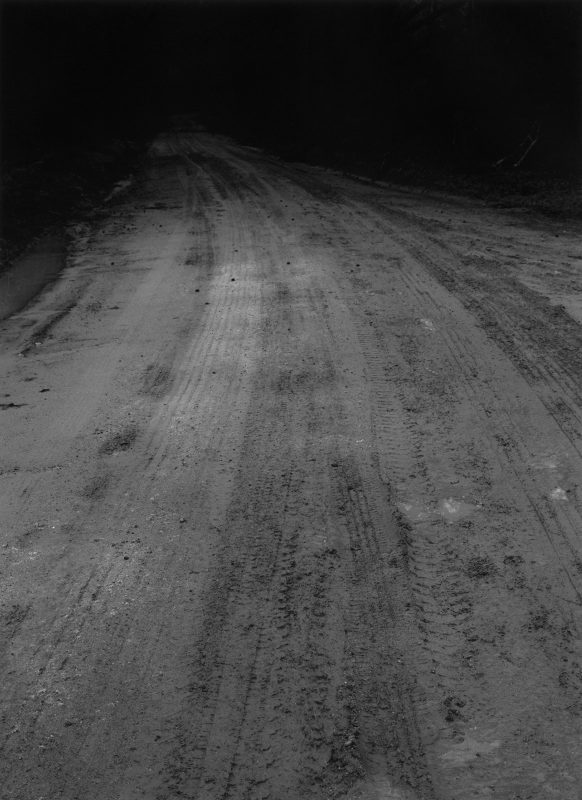

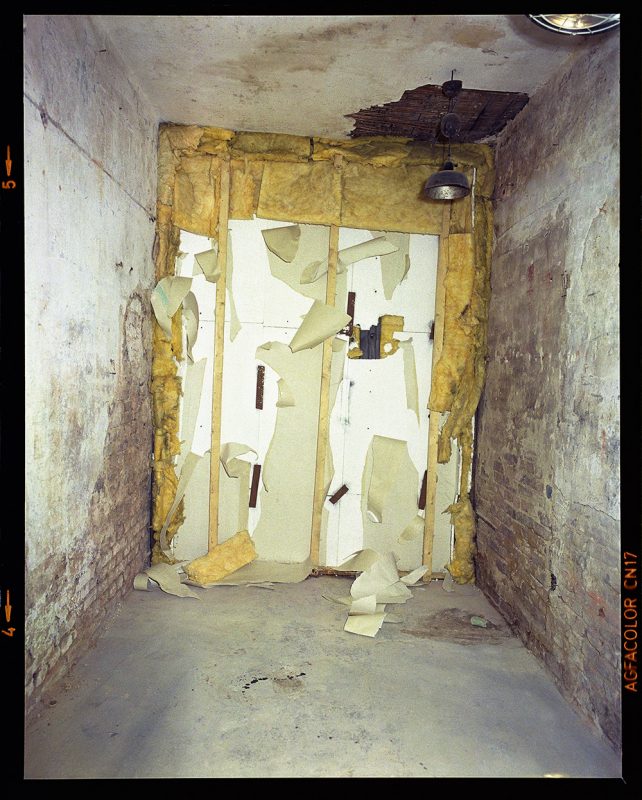

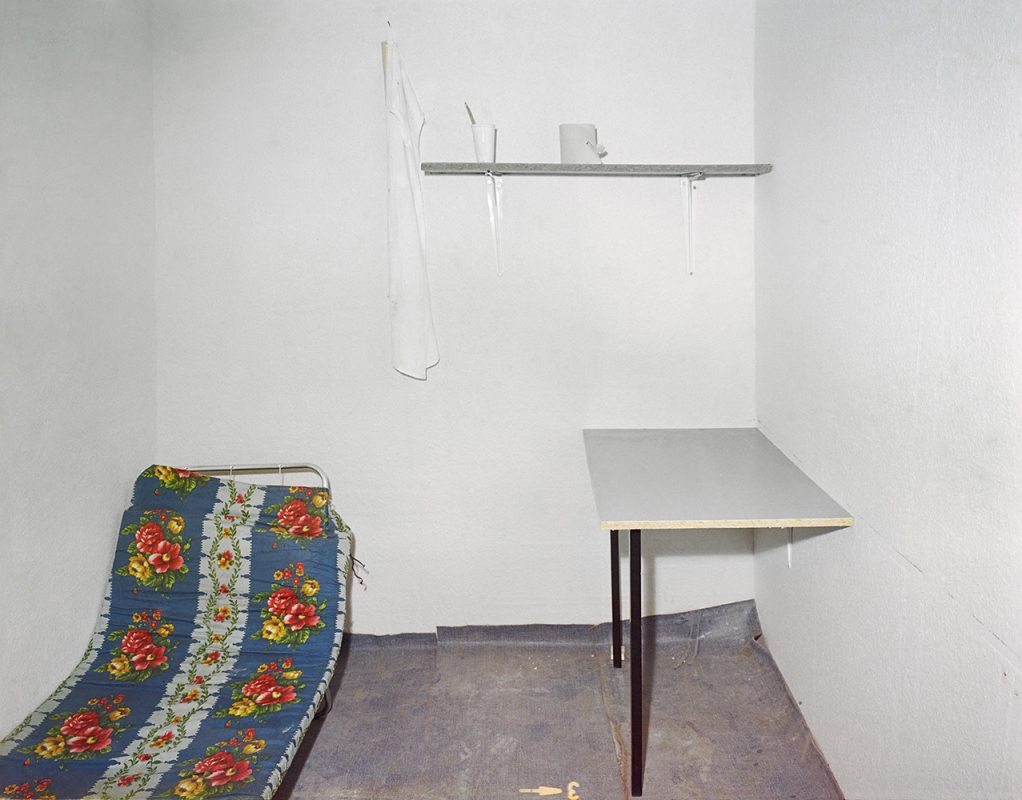

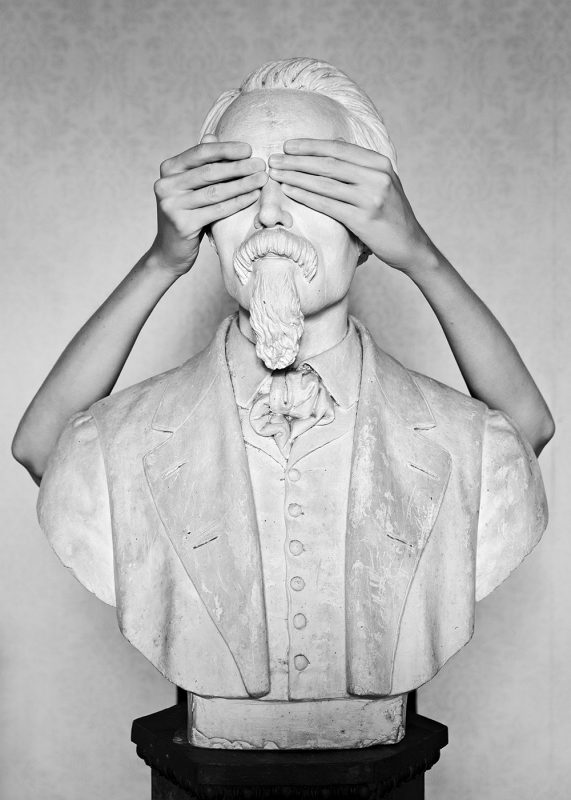

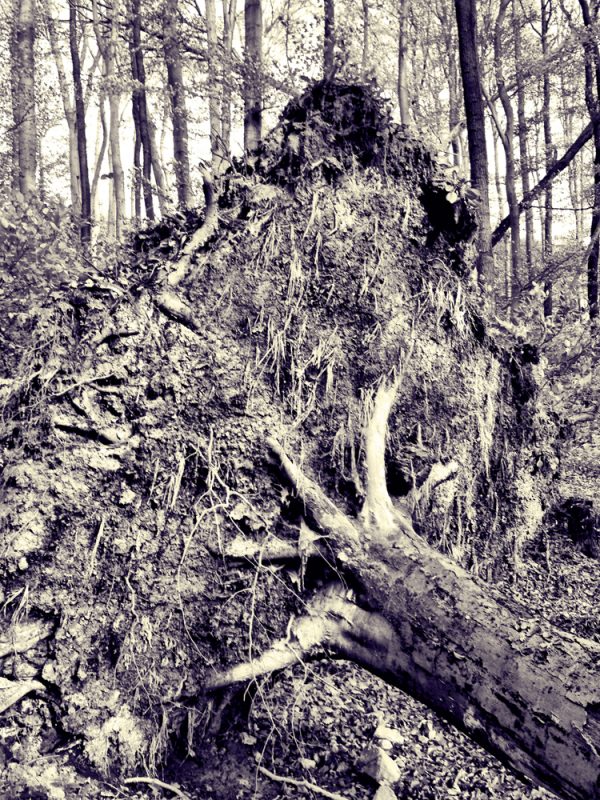

Here, as Parr says in his text, Gossage never courts the obvious but works around the edges, or around the back, sniffing out pictures like a dog sniffs out smells. In this trip, he was nearly always looking for the oblique angle, entirely appropriate for a society which so frequently presents a facade, or even a series of facades. His Britain is a land of walls and doorways, both of which define boundaries yet lead to places. In Gossage’s hands, the outcome seems ambiguous, although this is an affectionate rather than a critical look at our island.

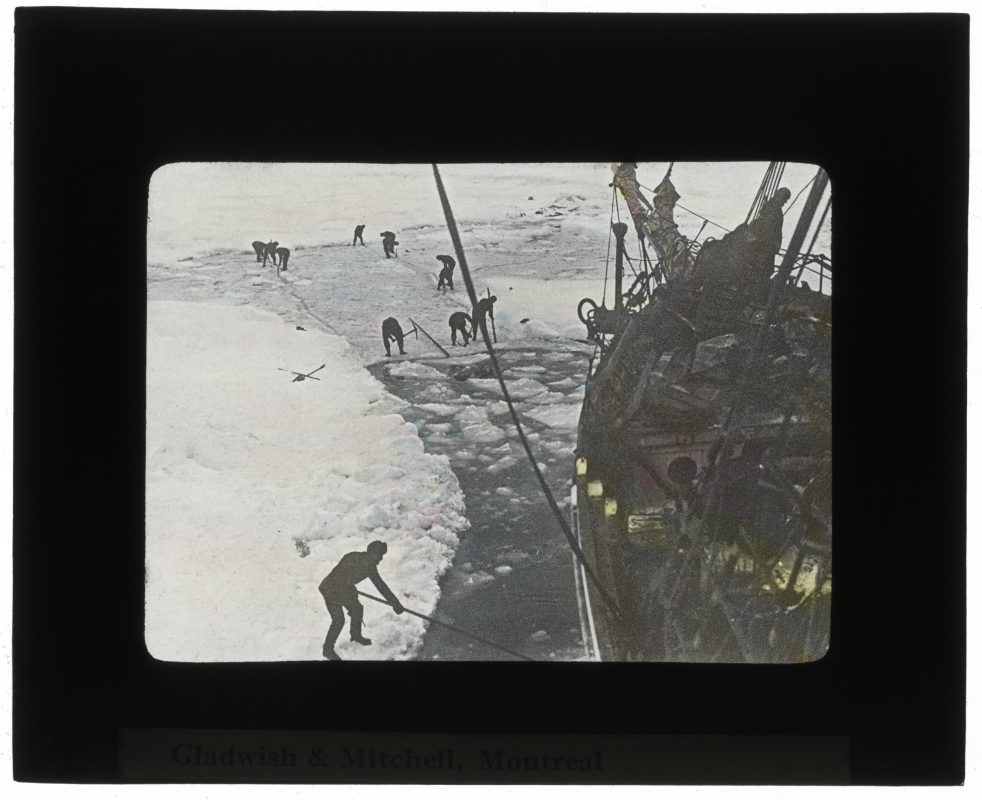

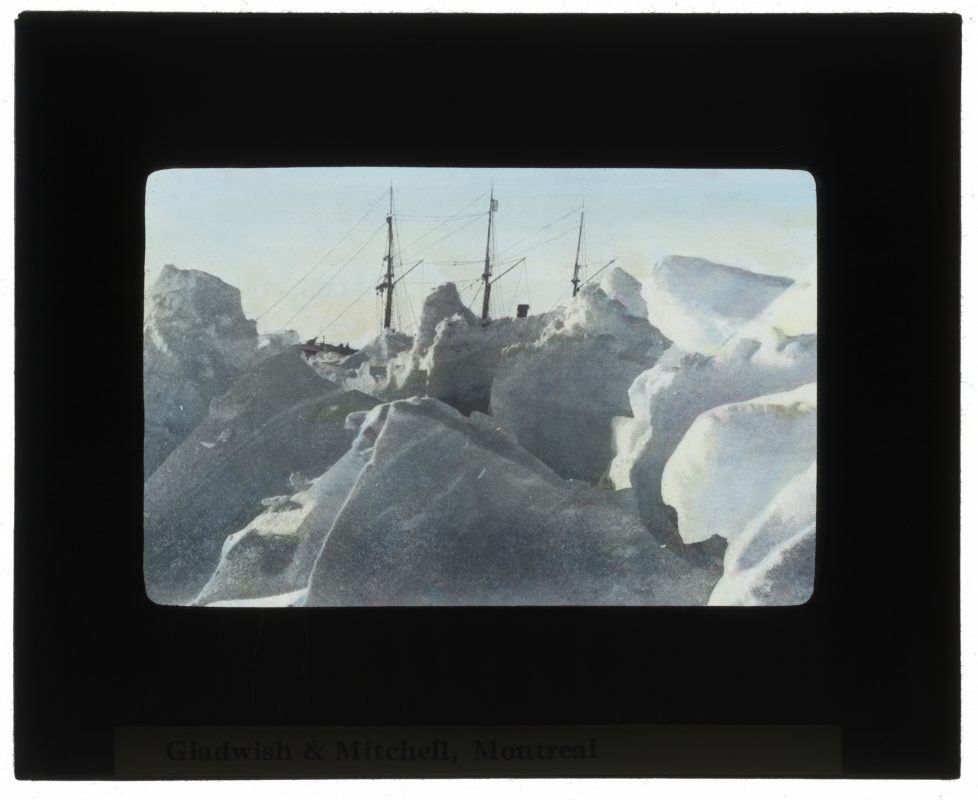

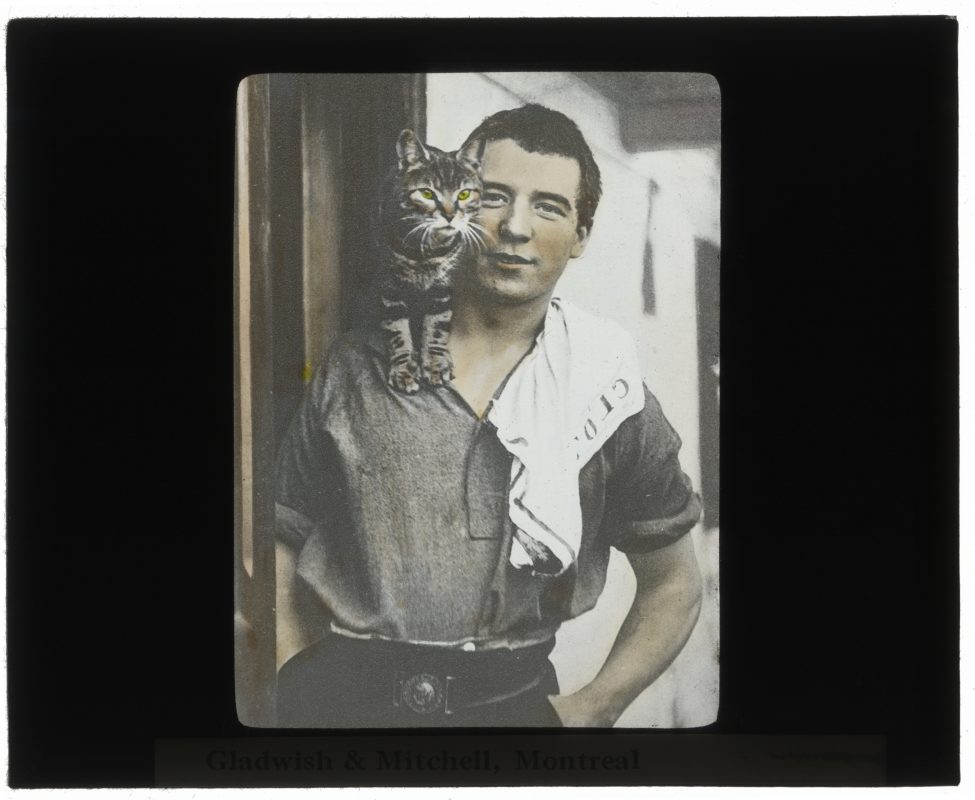

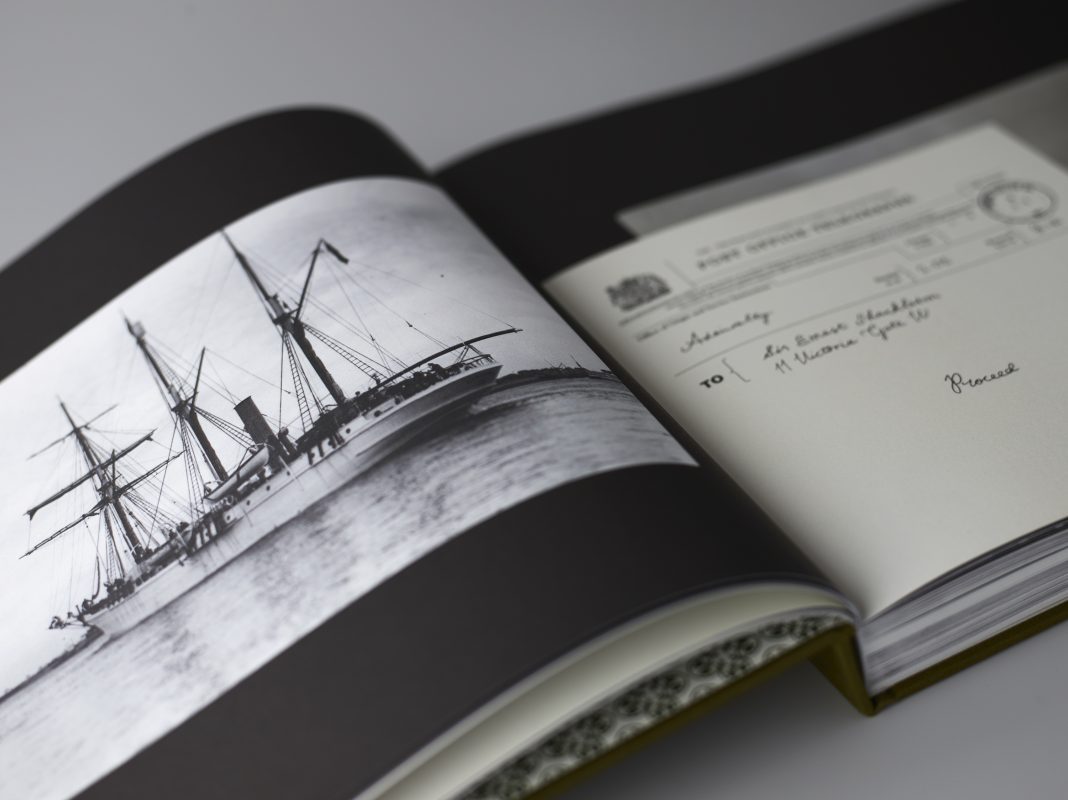

Gossage, like all great photographers, is a master at making the familiar seem newly minted. A few pages in, we come across some milk bottles on a front doorstep, an ultra-ordinary scene which yields a great picture. A mill and mill chimney are presented out of focus, so it is a mill as you’ve never quite seen it before. We then come to a Gossage – and British – speciality, the garden, in six pages of fecund, exuberant plots. We move on to more steps, garden sheds, doors, gates, and gate posts. There is a startling view of a fox walking down a path, and a glimpse of ‘historical’ Britain, in a framed picture of an ocean liner from when Britannia ruled the waves (and rammed icebergs). And there are stains. Only Gossage, I think, can make interesting pictures from stains on the pavement.

This book is not, primarily, about Britain, or even a travel diary, although of course, it encompasses these objectives. First and foremost, it is about what photographers do. That is, make pictures about touching the world. When Gossage was a teenager, his teacher, Lisette Model, advised him to go and look at the work of an old, half-forgotten French photographer called Atget if he wanted to learn how to put a photograph together. I would say to today’s teenage photographers, if you want to learn how to put a picture together, you couldn’t do much better than study John Gossage.

Looking Up Ben James – A Fable is a sheer pleasure, a beautifully crafted and well put together book that above all, contains photographs of the very highest quality. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist and Steidl. © John Gossage

—

Gerry Badger is a photographer, architect and photography critic of more than 40 years. His published books include Collecting Photography (2003) and monographs on John Gossage and Stephen Shore, as well as Phaidon’s 55s on Chris Killip (2001) and Eugene Atget (2001). In 2007 he published The Genius of Photography, the book of the BBC television series of the same name, and in 2010 The Pleasures of Good Photographs, an anthology of essays that was awarded the 2011 Infinity Writers’ Award from the International Center of Photography, New York. He also co-authored The Photobook: A History, Vol I, II and III with Martin Parr.