Krakow Photomonth 2017

The War From Here

Exhibition review by Duncan Wooldridge

We are encouraged to perceive of it as a striking, spectacular occurrence, but war is not one eventful instance of violence: it is the layering of multiple small violations that accrue and erupt. Thus conflict is sustained until one side is so dominant that any attack it makes is no longer legitimated by the promise of a reciprocal threat. It is a longer proposition than the spectacle of conflict: it begins before a gun is fired, and is felt long after. The political theorist Carl Von Clausewitz infamously stated that war is the continuation of politics by other means: not just a means of getting your way through violence, and the sign of a political project that goes beyond typical coercion. It emblematises an antagonistic, immovable politics, getting its way.

If war is the continuation of politics by other means, then the reverse must also be true: in our everyday politics and interactions, instances of war are also played out. There is war in forms of nationalism and patriotic fervour that posit the supremacy of a nation amongst more than 200 others; and there is war in the gains we seek over each other in the neo-liberal workspace. Violence can be tracked back from the site of armed conflict, to our sofas, and our devices, and our material wealth. That we do not draw connections between our material wealth and the conflict or exploitation it requires is one of the great achievements of capitalism.

The War From Here, curated by Gordon Macdonald as one of the keynote exhibitions of Krakow Photomonth 2017, is an exhibition of five artists who approach war from a different set of proximities, setting it much closer to us. They choose to be distant from the ‘theatre’ of war: they seek not theatricality, but origins, traces, and consequence. As such, it is one of the most striking exhibitions of war in recent times, because it resists the ‘over there’ condition of photojournalistic tradition, stressing tangible experiences, scars, and roots of violence.

At its entrance, Sophie Ristelhueber’s Eleven Blowups teases and undermines the reportage photograph, and acts an initial disruption of our expectations for the image. Installed as large-scale prints directly mounted to the surface of a phalanx of walls, they problematise photography’s rhetoric of de-authored transparency. This is the image not as a window, but as blockade: montaged from multiple images of bomb craters, some of which are Ristelhueber’s own and others that are drawn from media outlets, a composite real is made that brings together the image’s connection to the place it depicts, with its place of reception and encounter.

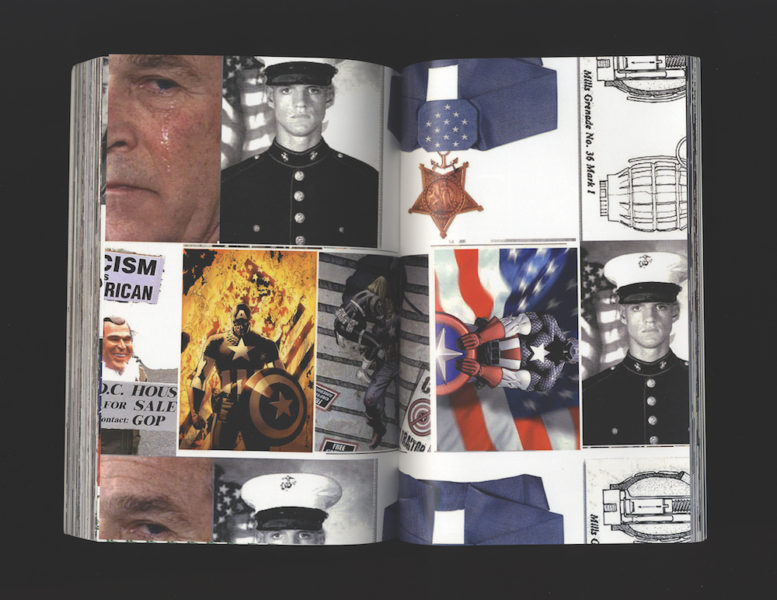

Nina Berman works within a recognisable documentary tradition, but uses it to show the domestic manifestations of America’s war on terror, challenging the way that that country’s militarisation is figured in daily life as elsewhere. Her project Homeland captures the full extent to which life is laced with military simulation and rhetorics of American power. One image shows B2 Stealth Bombers passing over beaches of Atlantic City. They participate in a celebratory display of military might that is triumphalist but exposing of the silent, lingering threat of a secretive military industry. Berman also depicts the militarisation of labour, as ordinary Americans are employed to act as Iraqi ‘terrorists’ in emergency drills. The war’s relationship to home is revealed by Berman as a series of constructs that produce the image of state power at the same time as constructing personal-imaginary images of terrorists and otherness. Here, war is a fantasy that displays little concern for that which exists outside of an American sense of might: documentary is suddenly a form that has courage to show a view beyond the generic humanism of the eyewitness.

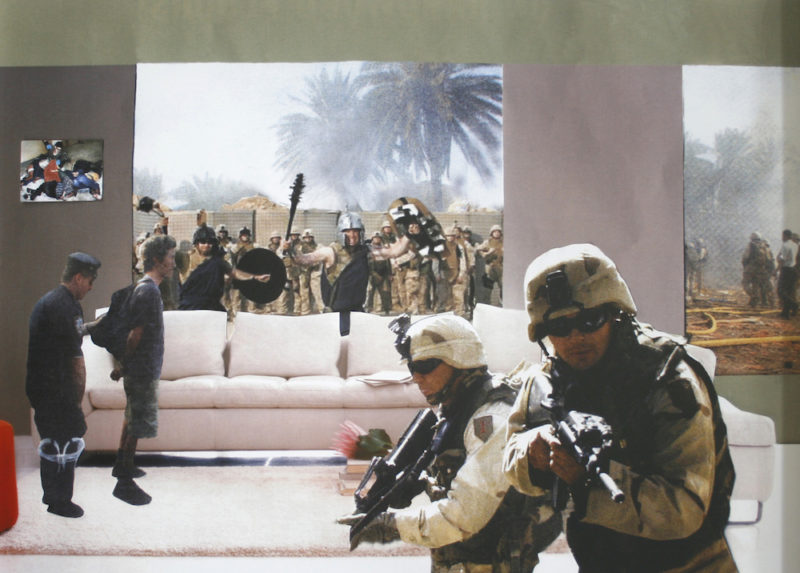

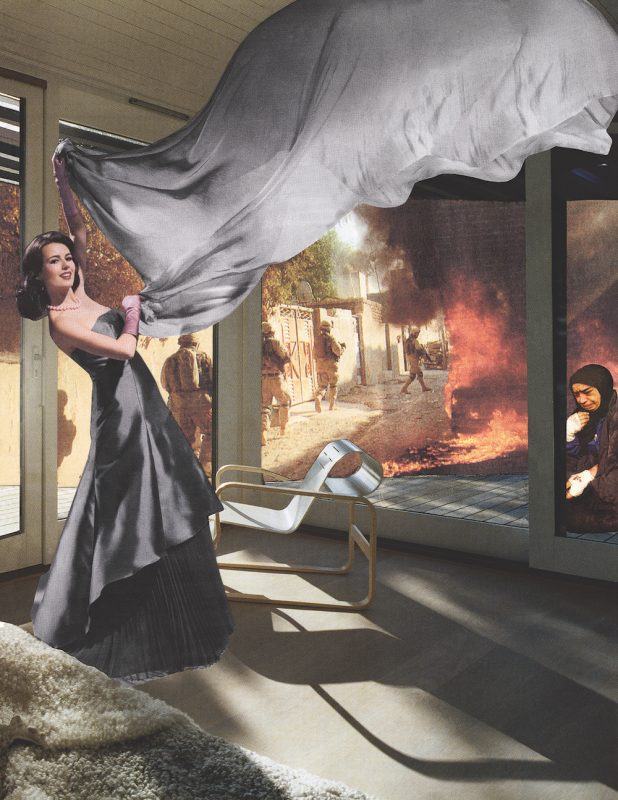

At the centre of the exhibition is Martha Rosler’s Bringing The War Home. Rosler’s montages directly equate the purpose and trauma of conflict with the luxury of the western home. Rosler makes clear that it is a largely exploited international labour force that extracts and forms the products of domestic luxury, which conflict maintains through its expansive project of installing democratic capitalist nation states. Rosler’s montages use the technical surfaces of the home (phones, televisions, pictures, and glass windowpanes) as openings to this conflict, as scenes that are mistaken as distant apparitions, but which are closely interlaced in a luxury that we have come to see as a desirable and freeing. Her later montages draw upon our various bodily postures with our mobile devices: laying upside down on a sofa, checking our pictures in our phone screens.

In a convincing and clear-sighted diversion from the usual obsession with war as a space of heroic individualism, Macdonald’s exhibition is unrepentantly social: it understands that war impacts upon a people, a multitude. As Ristelhueber, Berman and Rosler reveal how representations of war have been used to frame and limit our understanding, Lisa Barnard and Monica Haller evaluate the impacts of war through research upon the short and long-term experiences of conflict, whatever its ‘physical’ distance. Haller’s Veteran’s Book Project is structured around the first-hand encounter. 50 books present individual accounts from war, reclaiming the notion of the war veteran to include not just soldiers and military personnel, but also Iraqi and Afghan survivors. Each presents their own experience, an account that is always moving between the past and its impact upon the present. Some accounts are harrowing in places of course, but they are human and relatable first and foremost. Haller’s collection of a plethora of voices has a distinctive effect that repels the conventional desire to defer the war to some other place: it takes place between humans, as Judith Butler reminds us when she recalls the precarity of each human being as underwriting the necessity of the social. Haller posits that an array of voices can displace the dominant narratives of conflict and their contest the drive towards individual gain, and the illusions of a consequence-less accumulation.

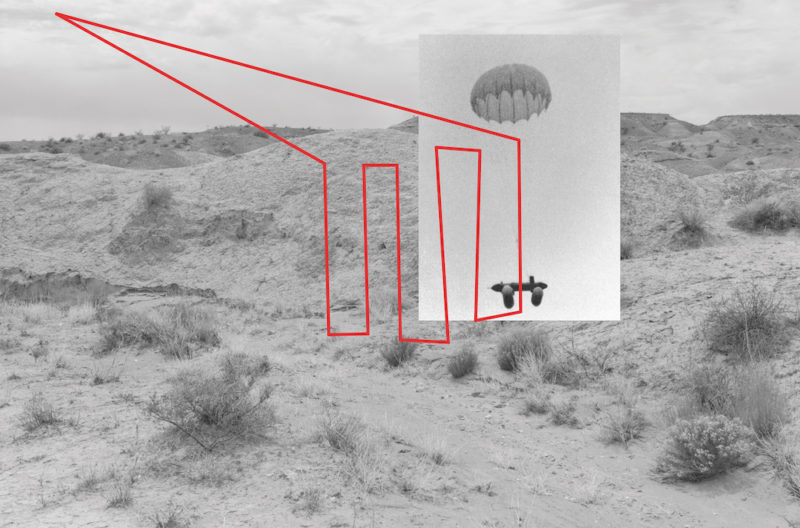

As Haller also suggests that we need to place the human back into the field of conflict, Lisa Barnard explores the military strategy of drones (or Unmanned Aerial Vehicle, UAV) operation, one manifestation of a technological war without the human (at least, this is what is claimed by its manufacturers and agents). The industry of war’s technological development – what Manuel De Landa calls the ‘machinic phylum’, feeding technological development that makes it to the consumer thereafter – seeks to displace the human in the place of machines, with a simplistic comparison between machinic efficiency and bodily fatigue. Barnard shows that the human effect remains.

As Adam Greenfield argues in his book Radical Technologies: The Design of Everday Life, the adoption of machinic and technological systems produces human effects in each of its manifestations. In Barnard’s work Whiplash Transition, an opening is found in the 40 minute drive between the military base and a drone pilot’s home. Whiplash transition is a term used by UAV pilots to describe the rupture between the locked-down enclosure of the drone mission, and the all-too-nearby comforts of the American city. In her installation, Barnard draws potent connections between the machinic vision of military devices, or the flying patterns of drones in strategic formations, and the fantasy-world of Las Vegas. In another part of the installation, a shipping crate displays a map of an arms fair on its top side: the uncomfortable meeting of armaments and basic human needs (food service counters, restrooms and cafes) is starkly revealed by the diagram.

Photography, with its concern for a slice of the action, is a common agent in the compression of war as something distant and unthinkable. The War From Here is an extraordinary call to see how it occurs right in front of us. Photography is capable of something more contextual, more critical, more enduring and penetrating. In this, one of the most convincing exhibitions about conflict and its reaches, we are called to see how war is something that surrounds us.

—

Duncan Wooldridge is an artist, writer and curator. He is also Course Director of the BA(Hons) Photography at Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London.

Image credits:

I-Opening of The War From Here at Bunkier Sztuki/Krakow Photomonth 2017, curated by Gordon Macdonald featuring Lisa Barnard, Nina Berman, Monica Haller and Sophie Ristelhueber.

II-Lisa Barnard, Lawnmower, from the Mapping the Territory series © Lisa Barnard.

III-Lisa Barnard, Object #3, from the Primitive Pieces series © Lisa Barnard.

IV-Lisa Barnard, American Flag, from the Not Learning from Anything series © Lisa Barnard.

V-Nina Berman, Bomb Iraq, Times Square, New York City, from the Homeland series, 2003 © Nina Berman | NOOR

VI-Nina Berman, Stealth bomber, Atlantic City, New Jersey, from the Homeland series, 2007 © Nina Berman | NOOR

VII-Monica Haller, The Veterans Book Project (VBP), library of 50 books, print on demand, page length varies, 2009–2014.

VIII-Monica Haller,Page spread from book by Ehren W. Tool, 2010.

IX-Martha Rosler, Cleaning the Drapes, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–1972 © Martha Rosler.

X-Martha Rosler, Gladiators, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series, 2008 © Martha Rosler.

XI-Martha Rosler, The Gray Drape, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series, 2008 © Martha Rosler.

All images courtesy of Krakow Photomonth.