Jenny Rova

Älskling. A self-portrait through the eyes of my lovers

Book review by Greg Hobson

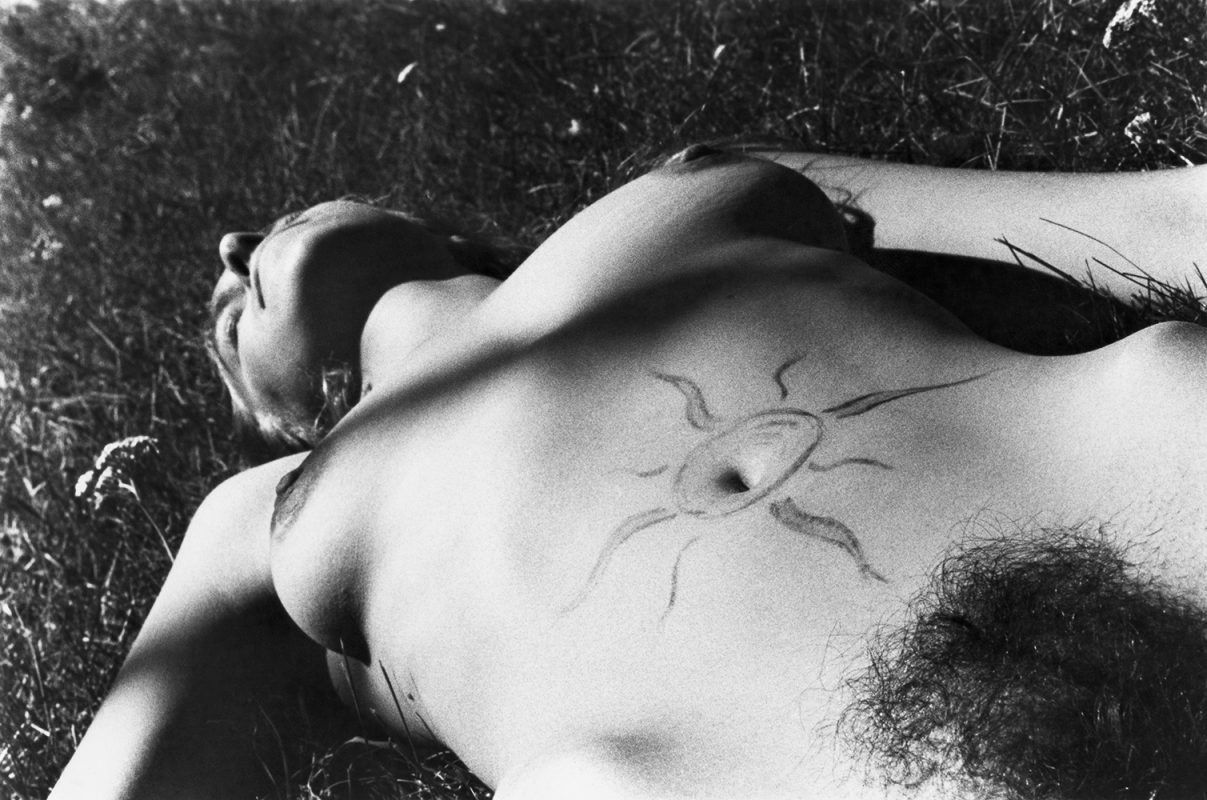

‘Later, Erica said she thought my response had something to do with a desire to leave a mark on another person’s body. “Skin is so soft” she said. “We’re easily cut and bruised. It’s not like she looks beaten or anything. It’s an ordinary little black and blue mark, but the way it’s painted makes it stick out. Its like he loved doing it, like he wanted to make a little wound that would last forever.”’

So reads an excerpt from What I Loved (2003) by Siri Hustvedt, which may serve as a useful coda for approaching Älskling. A self-portrait through the eyes of my lovers. Jenny Rova’s new book is her second with b.frank books, publishers of ‘carefully crafted and beautifully designed artist books’. Founded by Zurich-born photographer Roger Eberhard, and run together with Ester Vonplon, their titles are elegant and indeed smartly designed and their published artists always intriguing.

However, Älskling (which translates from Swedish as ‘sweetheart’) is perhaps best considered in the context of the now sold out first. Entitled I would also like to be. A work on jealousy, it documents Rova’s attempt to inhabit the life of her ex-lover by pasting her own photographs over those of her former boyfriend’s new partner, photographs she found of the couple on their respective Facebook sites. Unnerving and somewhat creepy, the work is nonetheless moving in its open and unabashed exploration of the very raw and overwhelming emotion of jealousy. Furthermore, it touches a contemporary nerve in its confrontation of Internet stalking, a curious and largely unacknowledged phenomena of navigating the complex codes of communication, in a disordered and melancholic 21st century society.

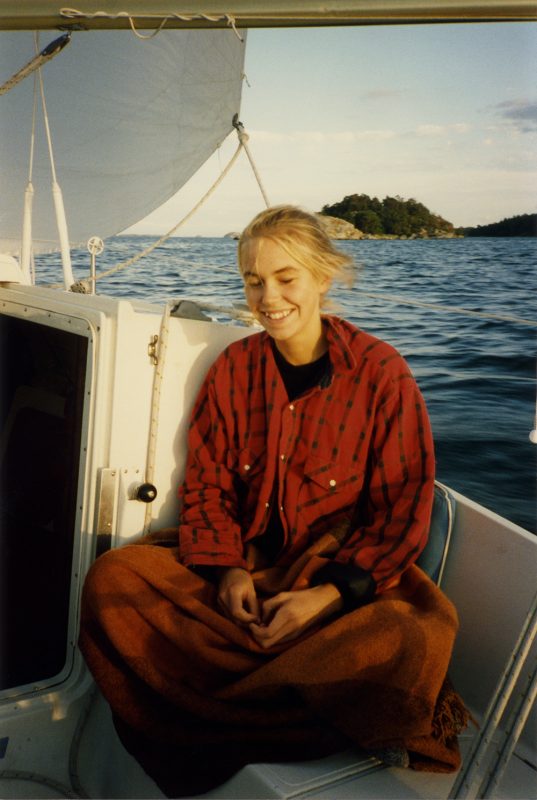

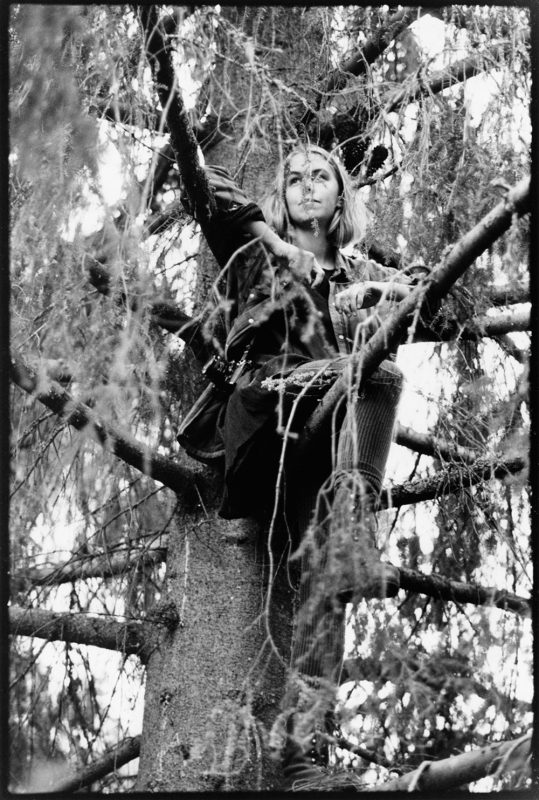

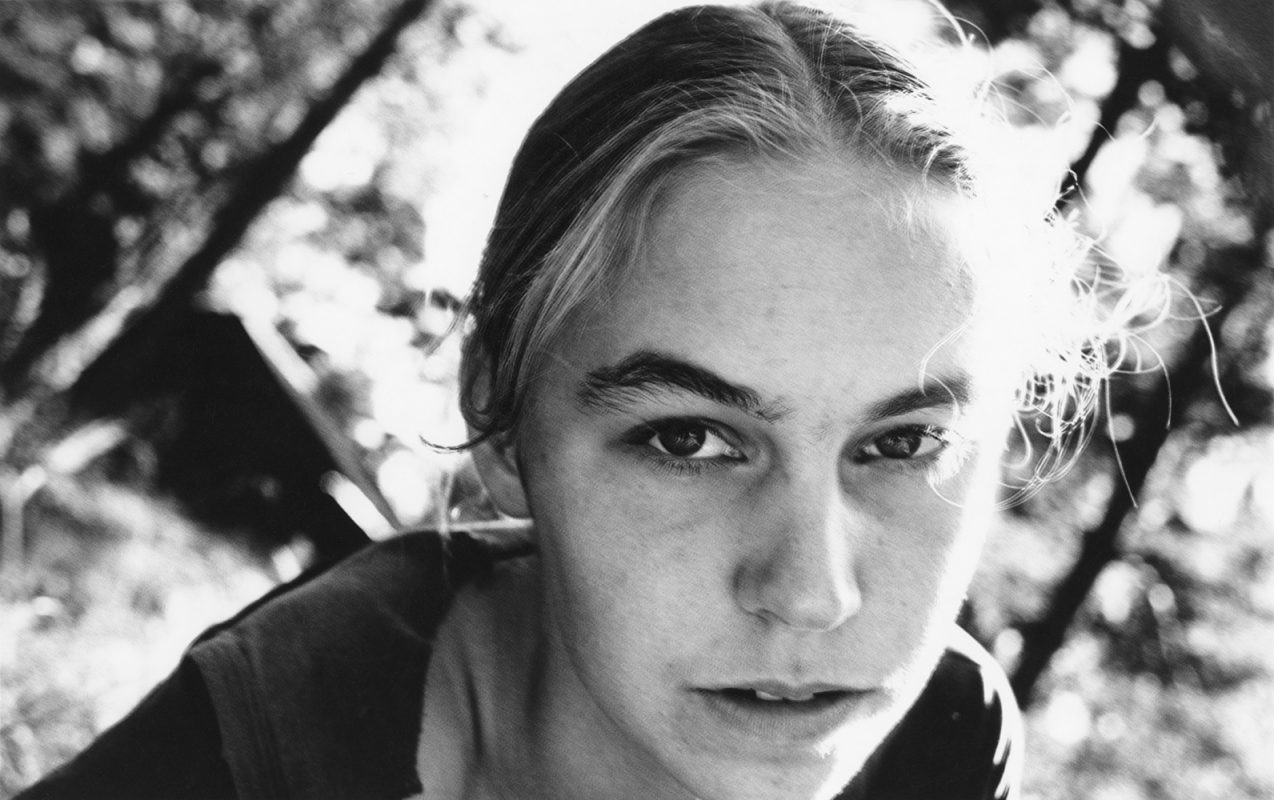

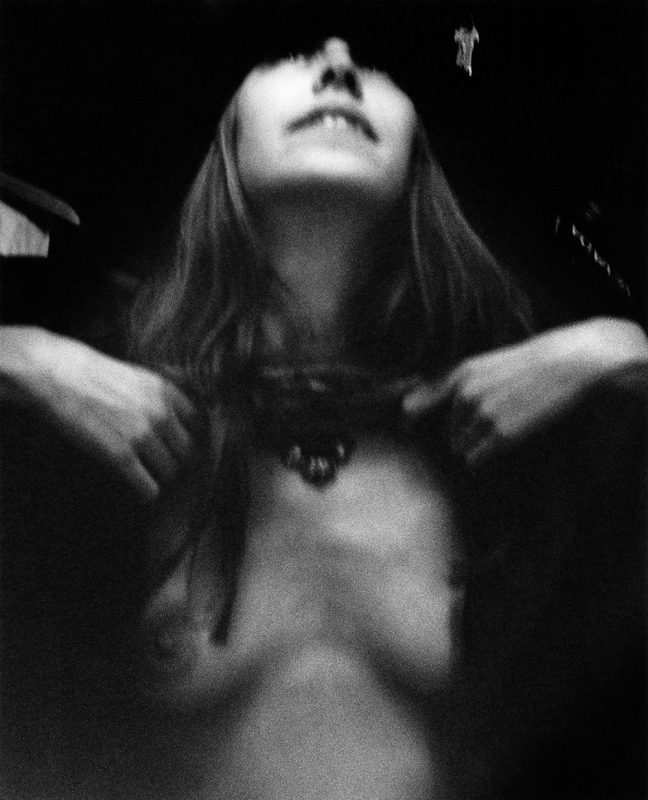

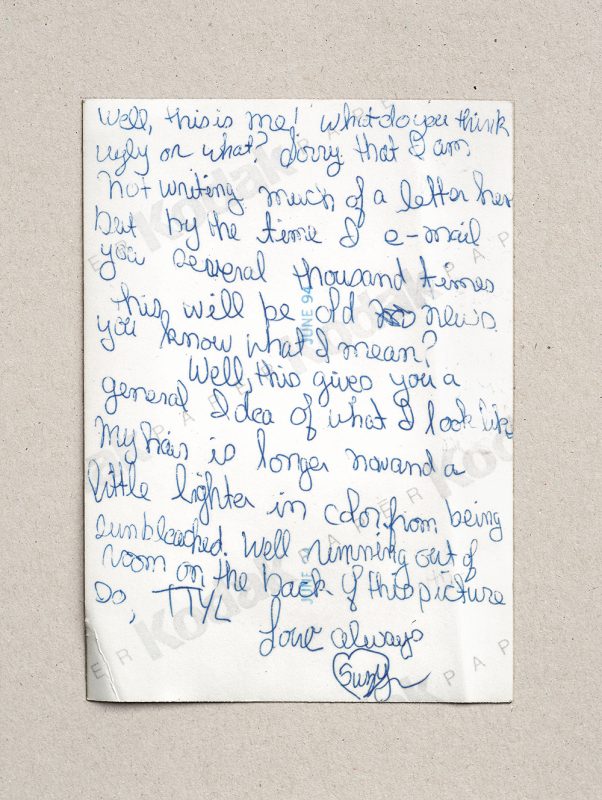

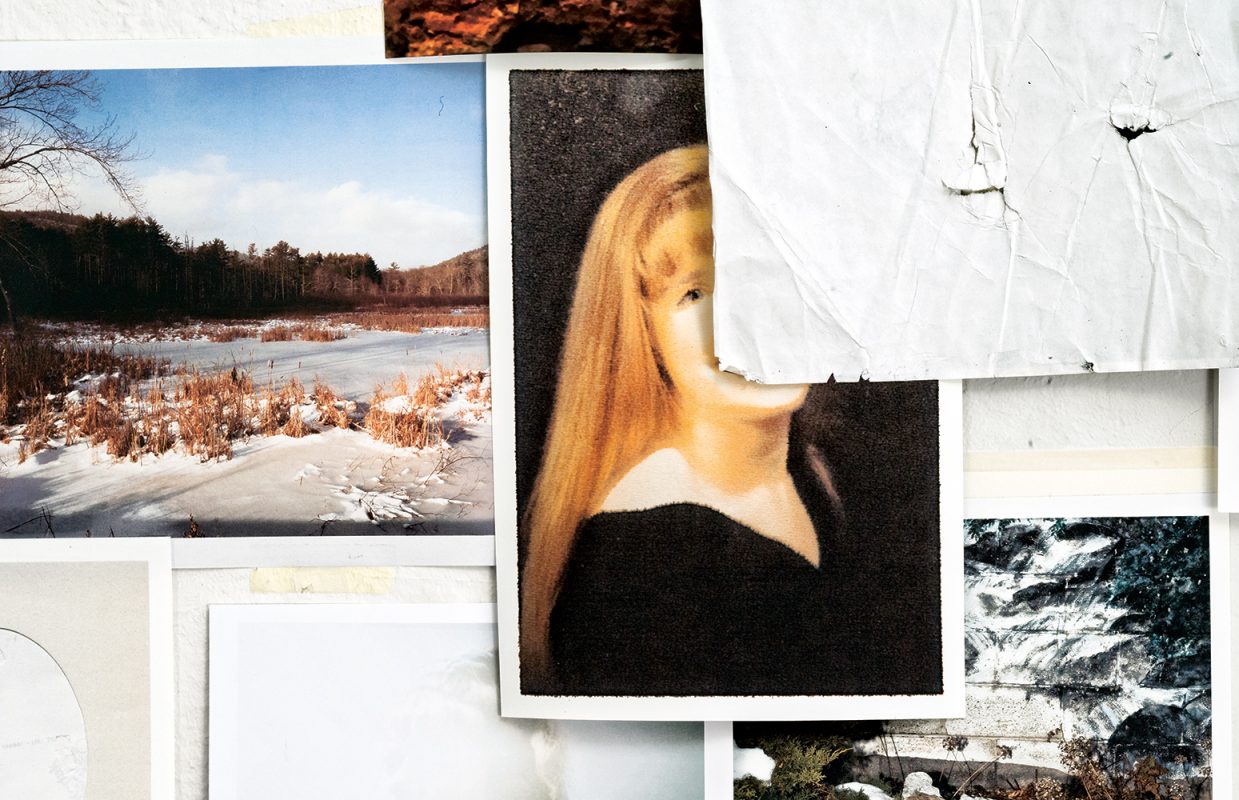

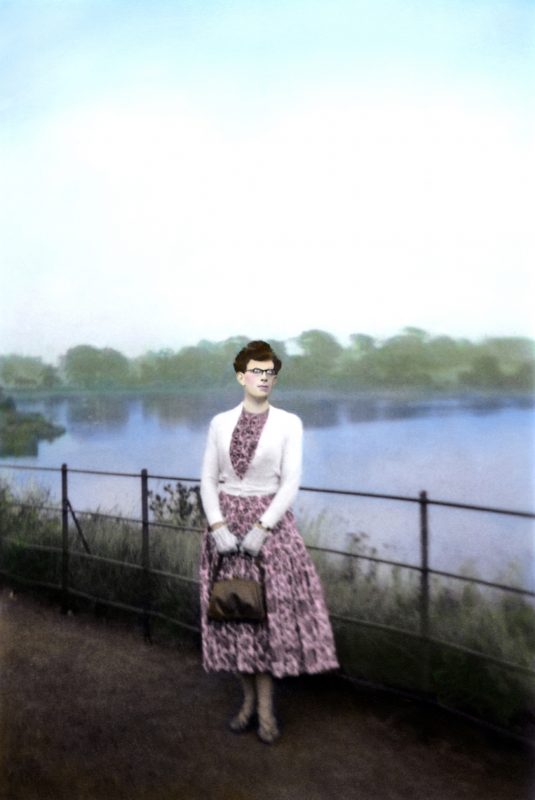

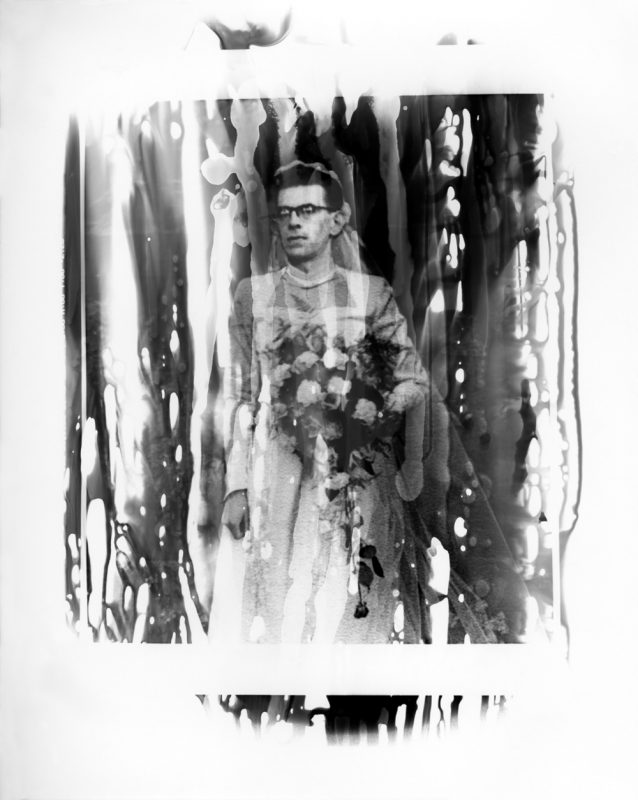

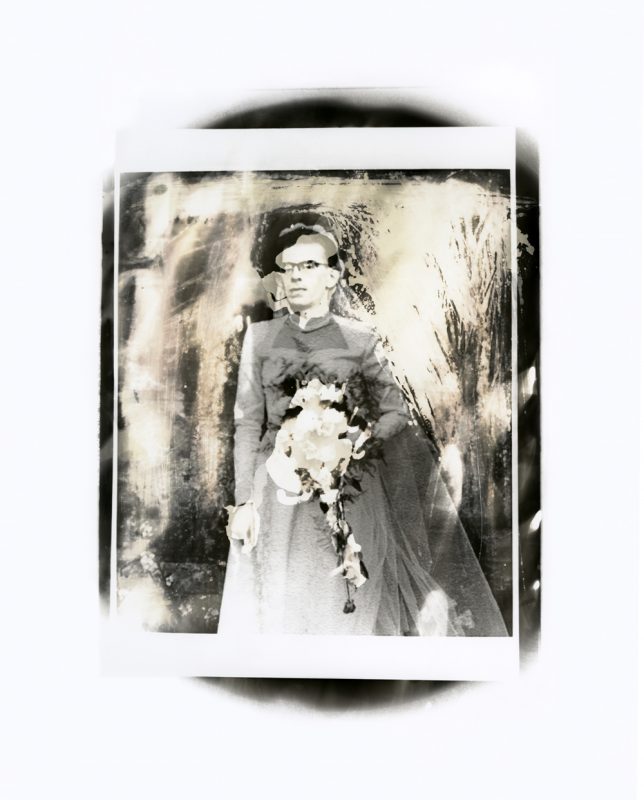

Älskling therefore sits as a companion piece to I would also like to be…, and in many respects, is part of a suite of works in which Rova frankly addresses her relationships, her body and the complex traffic between the two. In Älskling Rova has gathered together fifty-five photographs taken over a twenty-five year period by nine ex-boyfriends and lovers. Arranged chronologically, Rova presents the portraits as a biographical work and ‘an indirect portrait of the photographer, the partner behind the camera.’ She also describes them as capturing the way people look at one another when they are in love and ‘an attempt to capture closeness and attraction between two people within a photograph.’ This suggests that the photographs are romantic gestures and somewhat innocent in their execution, whereas they are in fact charged and complicated carriers of interwoven personal histories, emotions, desires, wishes and regrets.

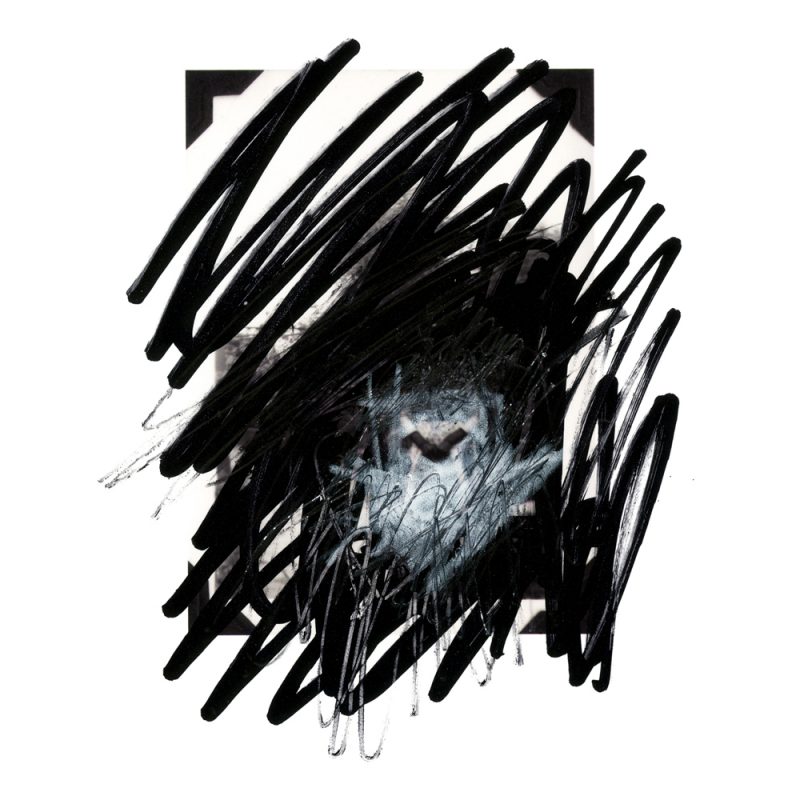

The initial transactions – to take the photographs and to be photographed – are lost in a journey that fragments the photographs from their original purpose as carriers a private history. Now presented in the public arena, they become the subjects for new authors and viewers. Rova as the holder of the material and Roger Eberhard as the editor of the book, permeate the images with new imaginations, which for Rova, are created with the benefit of hindsight and for Eberhard, his own fictions and interests in the photographs as an artist. As viewers we only have the pictures themselves to make our own connections with Rova’s, or even our own experiences. Rova appears to age little in the photographs so it is difficult to read them chronologically or ascribe them with any narrative weight. They appear instead as disconnected moments that are more or less sexualised, firstly by an omnipresent and very obvious male gaze, and secondly by the many photographs that show Rova naked or in various states of undress. There is also a strong sense of melancholy, or at least a certain wistfulness that runs throughout, as if there is an anticipation of an inevitable ending.

Seen alongside I would also like to be, the photographs in Älskling take on an additional depth. One of the authors of the photographs is the subject of the former book. This turns notions of intimacy and affection on their heads and the photographs in Älskling become part of a wider nexus that is related to emotional pain, rather than happiness. It is also a comment on objectification, both of and by Rova. No matter how one views the photographs in Älskling, and, regardless of the extent of Rova’s complicity, she is nonetheless objectified and the photographers’ feelings about, or for her are manifested in the photographs. In I would also like to be… Rova takes this one step further by using her ex-lover’s photographs without his permission and obliterating his new partner’s presence and replacing it with her own. Seen as a whole, the works feel polemical rather than affectionate and in Älskling, in particular, there is a sense of Rova really exploring her own emotional conundrums, as opposed to the often-intrusive gaze of the photographer.

This extension and overlapping of histories in Rova’s photographs are part of what makes them so curious. They are not easily categorised, and, while they appear familiar in their composition, mostly echoing poses from modern independent film, they are uncomfortable to look at, largely because they draw on such unflinchingly personal and private moments. In a large majority of the photographs Rova appears vulnerable and, in other instances, awkward and disturbingly childlike. Despite her own description of the book it is hard to read these photographs of pleasant times. In some pictures she hides her face, in others she stiffly exposes her body. Yet Rova has taken control of her representation and, in doing so, has partially wrested control of the images from their authors. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Jenny Rova

–

Working as Curator of Photographs at the National Media Museum in Bradford and Media Space in London between 1983 and 2016, Greg Hobson’s recent exhibitions include Only in England – Tony Ray Jones and Martin Parr (2013), Stranger Than Fiction: Joan Fontcuberta (2014), Revelations: Experiments in Photography (2015), and William Henry Fox Talbot: Dawn of the Photograph (2016). Since August 2016 Greg has been working as a freelance photography curator. Current and recent projects include Photo Oxford 2017, which he guest curated together with Tim Clark, curating People, Places and Things: Photographs from the W. W. Winter Archive for FORMAT International Photography Festival 2017, working with artist Mat Collishaw on Thresholds, a VR reconstruction of William Henry Fox Talbot’s 1839 exhibition of photogenic drawings for the Birmingham meeting of the British Association (which premiered at Photo London in May 2017) and co-curating A Green and Pleasant Land for Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne.