Saul Leiter

Retrospective

Essay by Francis Hodgson

The Photographers’ Gallery, London

22.01.16 — 03.04.16

Photographic history is pretty rum. It has become standard to read that William Eggleston was the first person to use colour as an ‘artistic choice’ and that his show at the MoMA in 1976 was the first show of colour at the museum. Both are nonsense. Alfred Stieglitz had of course made colour photographs by the Autochrome process and shown them at his 291 gallery as early as 1909. Edward Steichen worked in colour too, often brilliantly. And whether one considers such luminaries as Louise Dahl-Wolfe or Paul Outerbridge as ‘artists’ is a question for another place, but both certainly made work of high artistic intent to be distributed through commercial channels. And then there’s László Moholy-Nagy, of course, who was committed to working in colour after his arrival in the US in the late 1930s.

Eliot Porter showed colour photographs at MoMA, by the way, in 1943. Porter continues even now to be a photographer overlooked by fashion. It suits a certain number of people to overlook him, notably in the fine print market. Yet his commitment to environmental subjects much of interest today and his wonderful eye surely make him a candidate for a revival. And then there is Ernst Haas, who was a pioneer of another sort. That history is at long last beginning to be rewritten, as with Color Rush: American Photography from Stieglitz to Sherman, published by Aperture and the Milwaukee Art Museum in 2013, but it has been a long time coming.

Saul Leiter (1923-2013) almost vanished through this kind of sloppy thinking. Specialists knew he was included in Jane Livingston’s grouping of ‘New York School’ photographers in 1992. The great New York gallerist Howard Greenberg knew him from around that time. And there were others, too. Yet he only really took his place in public photographic history when the brilliant British historian Martin Harrison tracked him down for his monograph on Leiter’s Early Color in 2006. That book showed masterpiece after masterpiece – little views of New York, a miraculous combination of street photography and abstract art. Since then, many think they know Leiter. And a huge retrospective of some 400 pictures at the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg in 2012 (with a tome of a catalogue) did the rest. Leiter was firmly inserted, only months before his death, into the canon of photo-history.

It is worth noting that Leiter’s father was a great Talmudic scholar and his family wanted him to be a rabbi. In Tomas Leach’s documentary film on the photographer, In No Great Hurry, Leiter is heard to say (his tones unmistakably rabbinical) “My father from time to time descended into unkindness. The Leiter family is not as familiar with the notion of kindness as I believe they might have been or should have been. Greatness was important. Great scholarship was important. Intellectual achievement was important. Knowing was important. Knowing a great deal was important. Kindness? Well, if kindness interfered with the pursuit of learning and greatness and scholarship – too bad. Get rid of it.” There’s sadness there, which might explain a lot. There is a loneliness about his photographs, which never quite disappears.

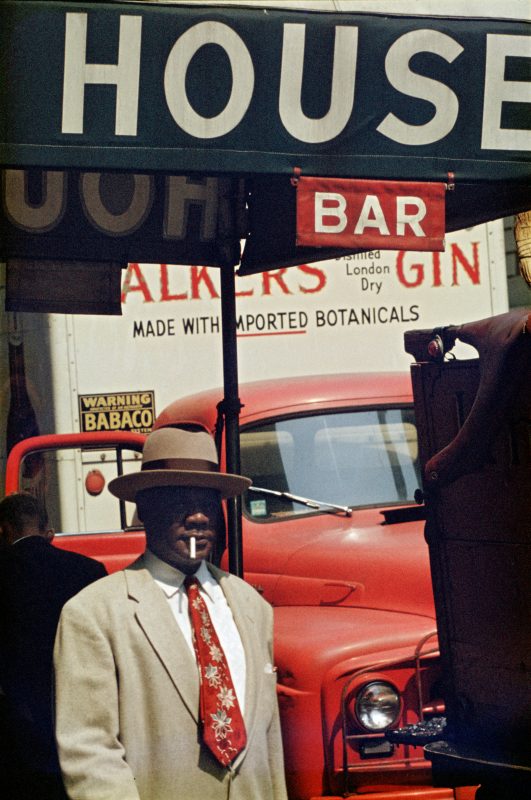

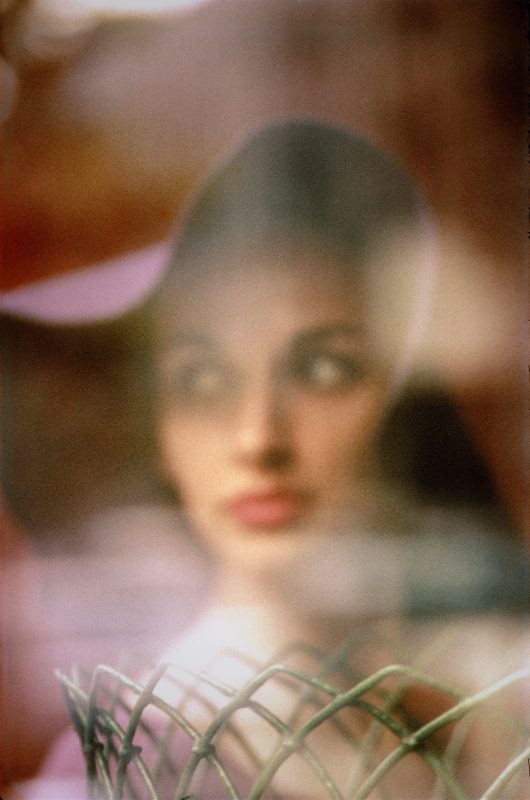

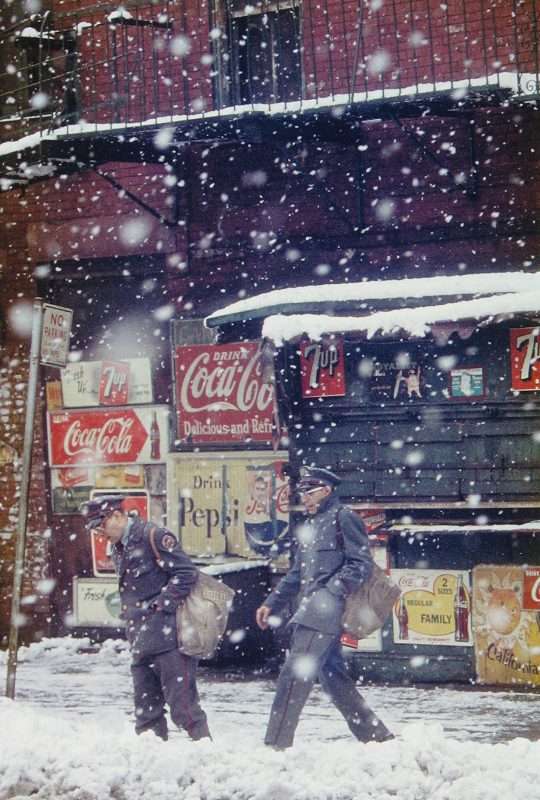

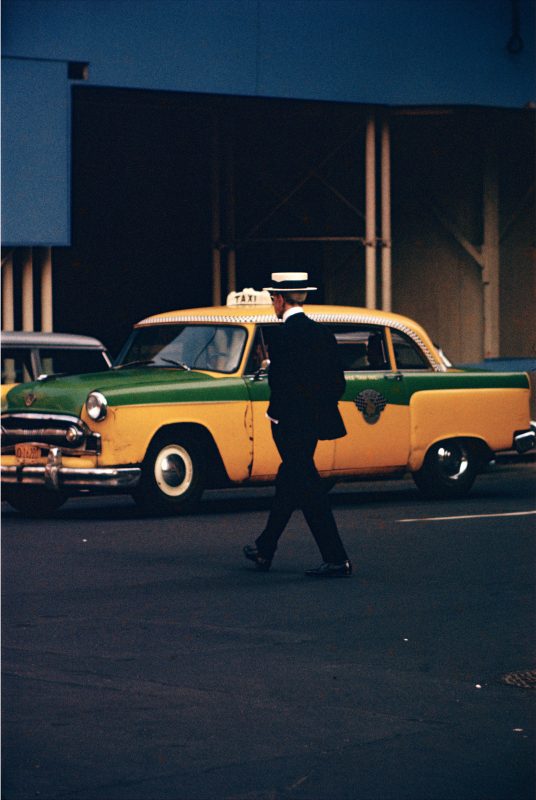

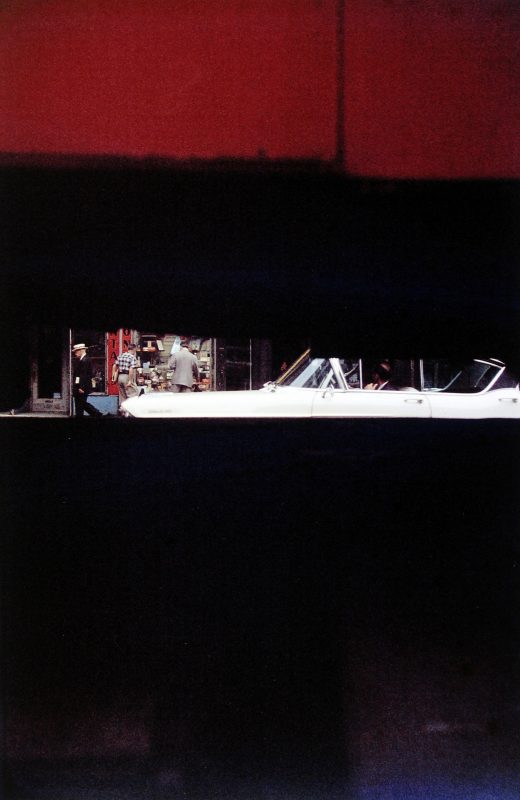

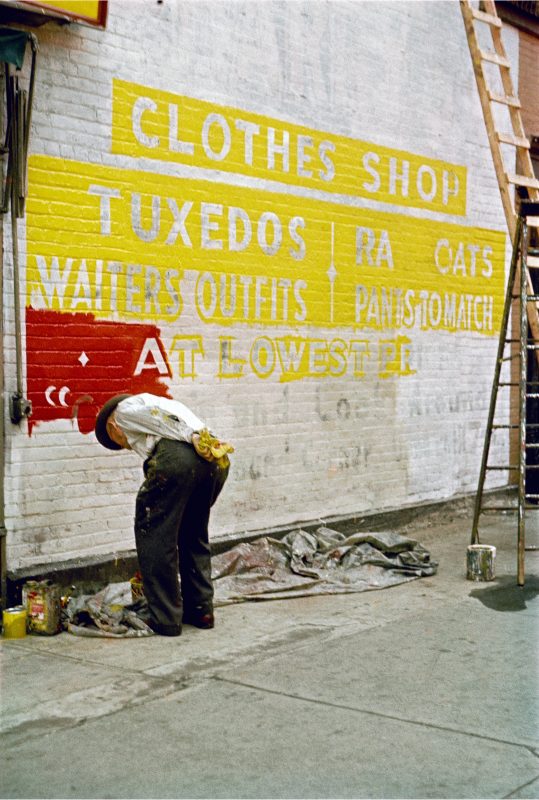

Born in Pittsburgh, Leiter arrived in New York with plans to become a painter; he knew already he would disappoint the expectations others had placed upon him. His standard view of life is from the outside of whatever he is looking at, shielded by multiple layers of glass (and that glass often steamed up or dripping condensation) or peeping between boards or blinds. It is here that he differs from other New Yorkers, the type of William Klein or Garry Winogrand, who were quite happy in the thickest press of the crowd. And he differs, too, from those, such as Helen Levitt, who made tableaux of the people she found on the streets, careful compositions with a story built into each. Leiter never did that. The word is overused, but nevertheless he is a kind of existentialist photographer, dealing in the lost moments between times. Leiter’s characters are almost never defined by the role they play or by their status in society. They simply are. They may be waiting for a bus or maybe a lover; they may be about to become bus riders or girlfriends; but Leiter finds them in between those roles.

He could be a marvellous painter. In one enormous respect he went against the grain of his Abstract Expressionist contemporaries in the East Village. He never painted big. Painting at the edge of abstraction in gaudy colours that I’m tempted to call Fauvist, he layered thickly but on tiny supports. Whether from poverty or from a kind of consciousness of the weight of surfaces, he often used what he had to hand and painted on that – packaging, printed materials, and in one spectacular case, on photographs.

The story goes that he was invited to make a book of photographic nudes, a book, which never materialised. Then, ten years later, in his studio, surrounded by the stack of unused prints, he started to paint on them. In the best of them, the paint acts to clothe the figures, not covering them entirely, but adding something more. The painted surfaces act as a caress – one almost sees the brush as stroking the body – but once the caressing is done, the body is clothed. Not all of the images, it must be said, are good. Leiter was a hoarder and too many of his tests and mistakes survive. It’s not quite clear why he persuaded so many young women to pose for him nude. In the documentary, he talks self-effacingly about his “secret life as a creep”, but it may not entirely be a joke. The unpainted nudes are not particularly good at all; although it is noticeable how relaxed the sitters always are. Leiter was a gentle man, devoid of any great ambition or drive. “I aspire to be unimportant”, he said.

Yet for a number of years he earned his living in fashion, at Harper’s Bazaar, no less, before his name began to get him gigs elsewhere. He made no great bones about fashion. His fellow New Yorker, Louis Faurer, was rather ashamed of working in the industry. Robert Frank wasn’t especially cut out for it, but he saw no shame in it. Unlike the street views and indeed his paintings, the fashion pictures were made for other people, but he clearly only modified his way of seeing. At their best, Leiter’s fashion photographs have the same shyly voyeuristic sense as his own work. He’s never openly pervy – like, say, Miroslav Tichy – but even in the magazines the pictures are often a little off-key. This is man who always preferred to see than be seen. Kate Stevens (of the HackelBury gallery in London) told me a story that Faurer once kept a model waiting a terribly long time at a meeting place out in the open. When he finally showed up, he dismissed her. He had already done the pictures while she was waiting for him. Was that cruelty? Or shyness? Or a bit of both?

By the time you read this, it will be too late to see the glorious HackelBury exhibition of his paintings. The Photographers’ Gallery show, which is a boiled-down version of the Hamburg show of a few years ago, is still on. It gives a nice overview of his whole career. But what to make of Saul Leiter himself? The colour street views are certainly the highpoint. They have something of the almost mystical gentleness of colour from the mournful little Polaroids André Kertész made of the glass objects on his window-sill high above Washington Square, after the death of his wife, Elizabeth.

Leiter’s effects owe much to Kodachrome (which was a slide film) and it may be for that reason that they have such a strong appeal right now. It used to be that viewing photographs backlit was a rare privilege reserved for professionals equipped with light-boxes. Only slide shows gave any chance of seeing pictures backlit (or seemingly so). That’s partly why Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency was always originally shown as a slide show. Pictures just have much more intimacy that way – which obviously suits Goldin’s subject matter to perfection. But then along came digital, and almost all pictures were suddenly seen backlit on our screens. That may be why certain techniques that were hardly considered before now look so natural to us.

Leiter painted in mixed colours at the height of their brightness: turquoises, oranges, acid greens. But he photographed in primary colours, muted right down through misting and screens and that wonderful bloom of damped-down Kodachrome. His favourite colour was red. He returns to it again and again. These are Leiter’s colours: never shrill, never too loud. Once you recognise how he does it, there’s something about his manner, which lies well with his successors. It is hard, for example, to imagine that the influence of Saul Leiter is not lurking somewhere behind Paul Graham’s shift from clear factual seeing to his later, less overt manner.

Clearly, Leiter was a saddened man. He photographed mainly for himself and searched, through his pictures, for little bits of happiness where he could find them. He probably didn’t have the sheer bravura technical virtuosity and invention of an Erwin Blumenfeld (though, it would be interesting to show the two of them together), but he had absolute mastery of the emotional effects of colour. The splash of yellow, for example, of a passing taxi could be joy, if only for a moment. “There are,” he said, “the things that are out in the open and there are the things that are hidden; and life – the real world – has more to do with what is hidden.” That’s a subtle motto for a photographer; he was a subtle man, working brilliantly in colour, long before Eggleston. ♦

All images courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery. © Saul Leiter

—

Francis Hodgson is Professor in the Culture of Photography at The University of Brighton. His former roles include photography critic for the Financial Times, and Head of Photographs at Sotheby’s, London. He is also a co-founder of the leading photography prize the Prix Pictet