Top 10

Photobooks of 2022

Selected by Alex Merola

As the year draws to a close, an annual tribute to some of the exceptional photobook releases that caught our eye during 2022 – selected by Assistant Editor, Alex Merola.

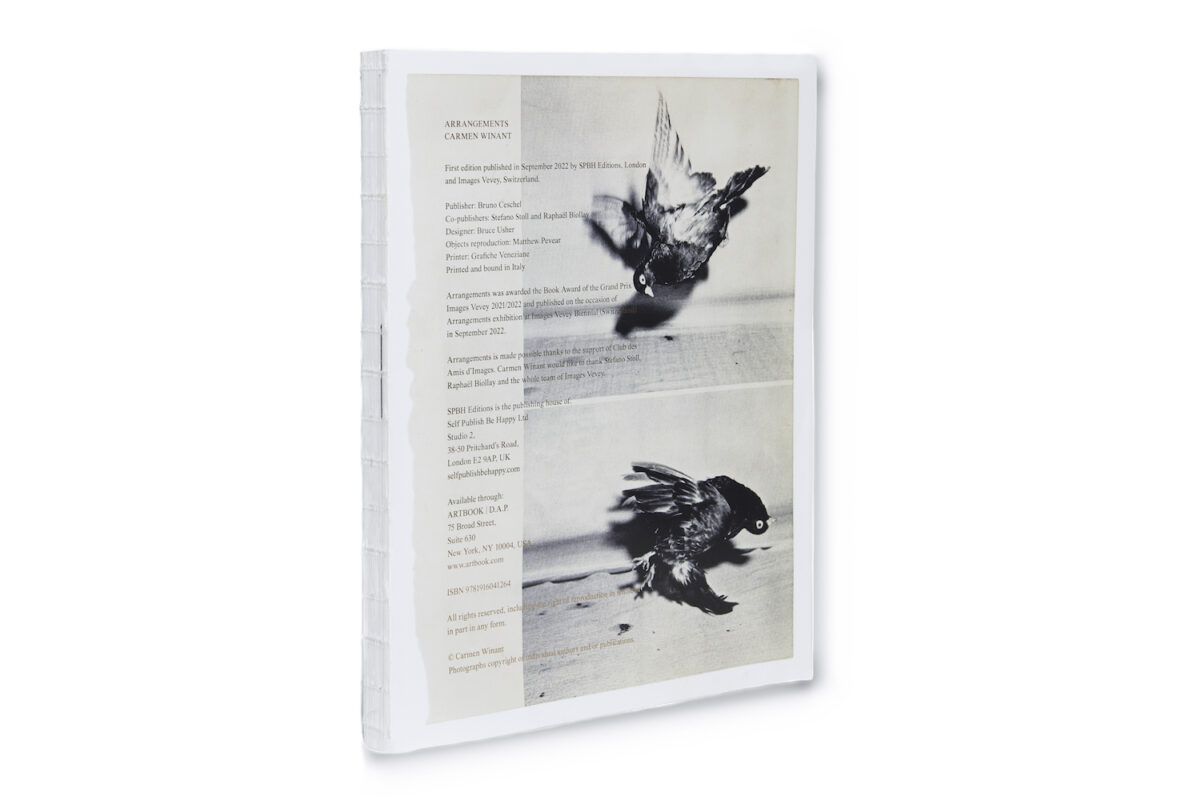

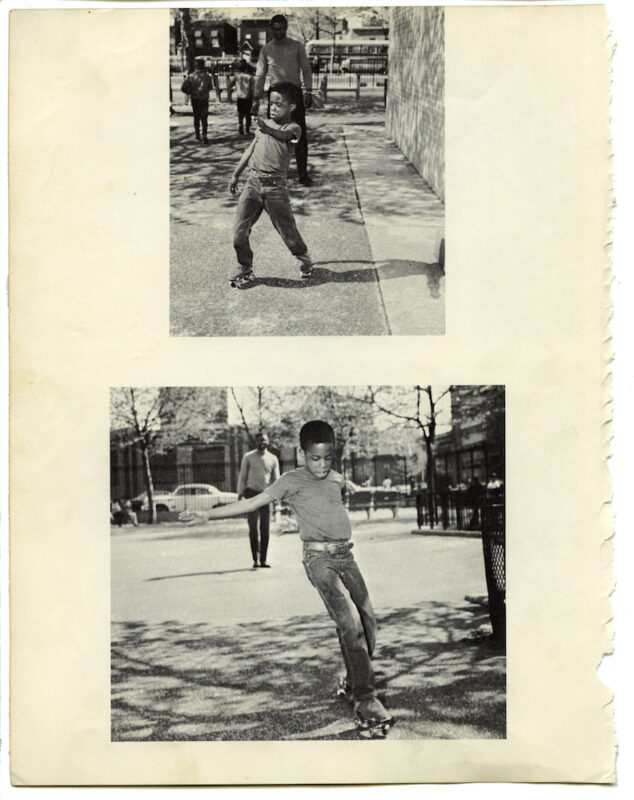

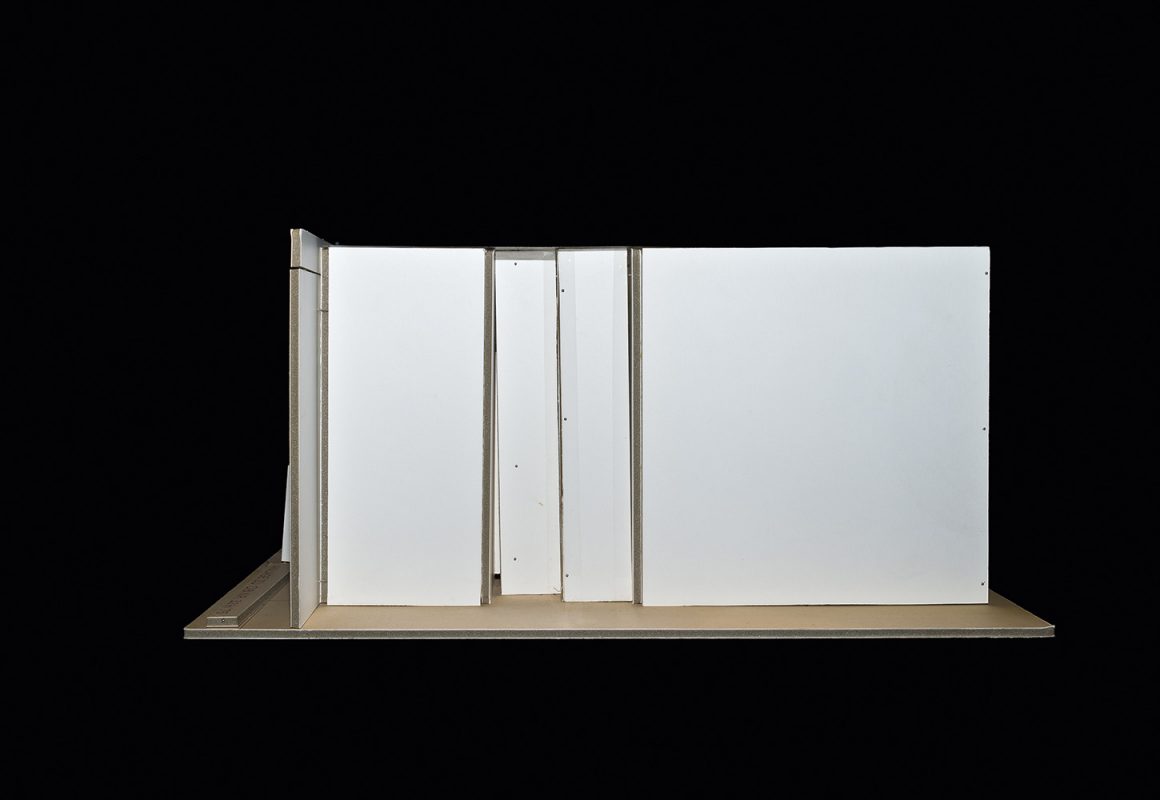

1. Carmen Winant, Arrangements

Self Publish, Be Happy / Images Vevey

The book – as both medium and as subject – is probed to its expansive potential in Carmen Winant’s latest. Large, elegant but always “DIY” in feel, with its rough, naked spine, Arrangements is one of those books that is both specific and sweeping at the same time. For the once discrete and disparate tearsheets that bound it together – depicting Bikram yoga classes, beauty pageants, moonwalks, childbirth, tantric sex and the young Malcolm X – have been decontextualised to conjure wonderfully capacious constellations which, as a whole, wrestle with, and trouble, the notion of “theme”. Most admirable is Winant’s insistence on labour; inherent not only in the (ever-visible) tears of each page, but also in the collaborative networks that enable the making and sharing of a book, foregrounded through the detailing of the designer, printer, distributor and, of course, publishers Self Publish, Be Happy and Images Vevey on the graceful front-cover. Whilst this is a book that could have been subject to an infinite number of rearrangements still, the strength of the “arrangement” Winant lies in its courage: the courage to put something out into the world; something confounding and generous in equal measure.

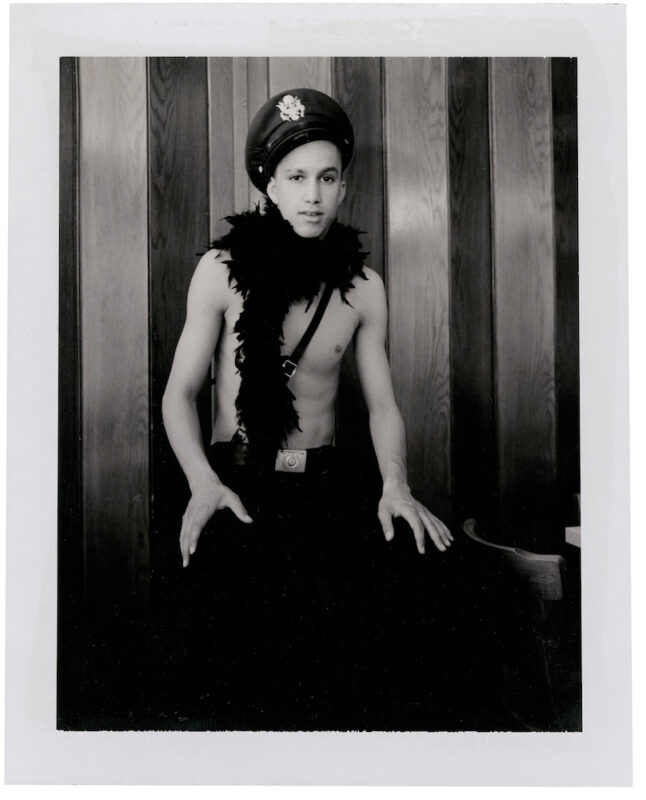

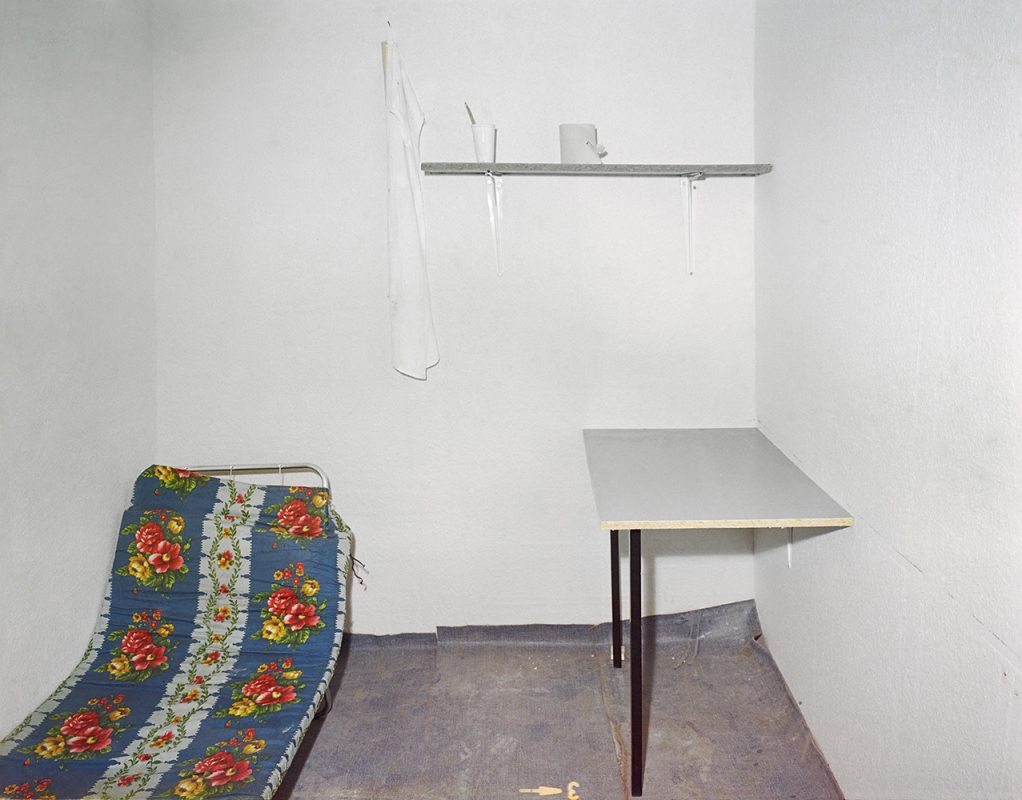

As strong as the taboos it touches, Collier Schorr’s third chapter in the Forests and Fields series is over a decade in the making and well worth the wait. Her many revisions have resulted in an unnerving book, extending Schorr’s investigations into ancestral responsibility through the mythos of the small town of Schwäbisch Gmünd, a synecdoche for German history. A finely-calibrated blend of history and fiction, the sequencing moves through Polaroids picturing crucifixes, flora and androgynous boys, at their moment of ripening, in and out of Nazi uniform. Invoking the performative history of fetishism and uniform – with references to Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter (1974) as well as August Sander’s portrait of Hitler’s guard – Schorr is clearly working with the reactions the young men portray when they are confronted with artifacts of the Third Reich. Her anachronisms are provocative and transgressive, but also intimate and cathartic, resonating further given that Schorr is of Jewish descent, while most of her subjects are not. It is commendable how Schorr has sought to uncover the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of traumatic history, inherited and imagined. Ultimately, this book does not lose itself to nostalgia, even if it is hinged to it. For the fleeting Polaroid frames land on the now, shedding light a war whose ripple effects persist.

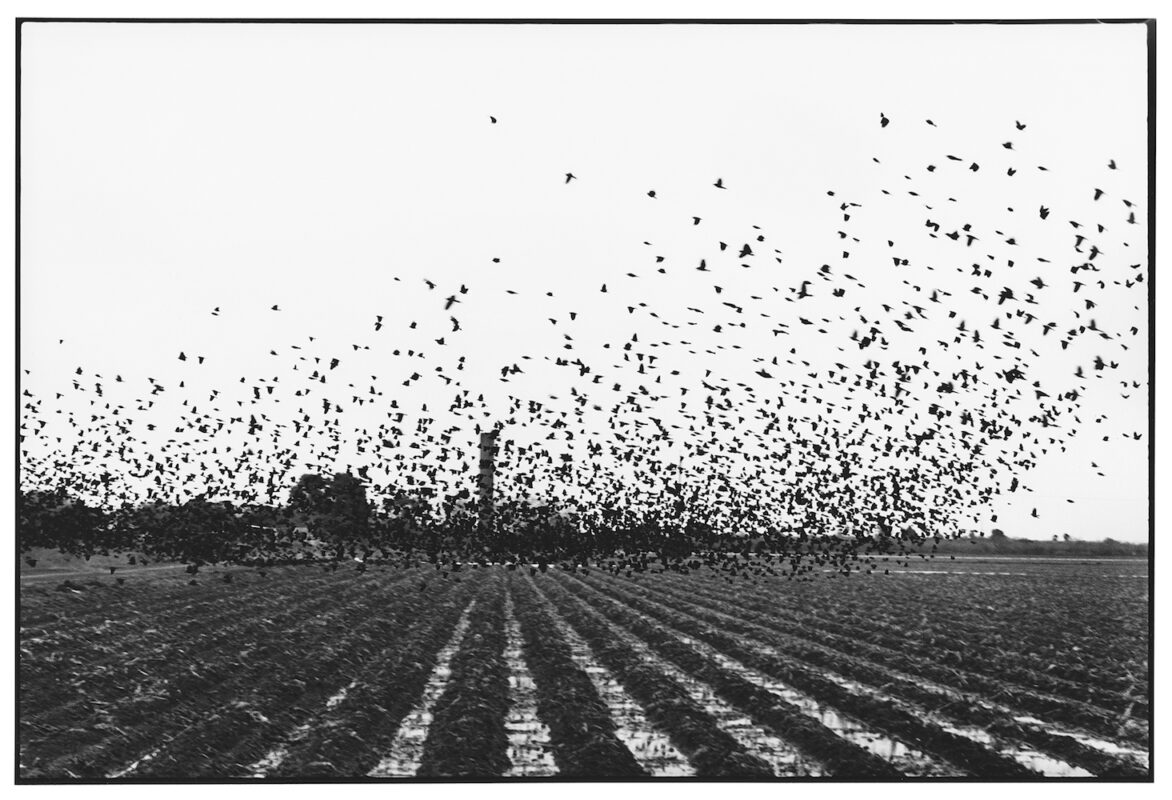

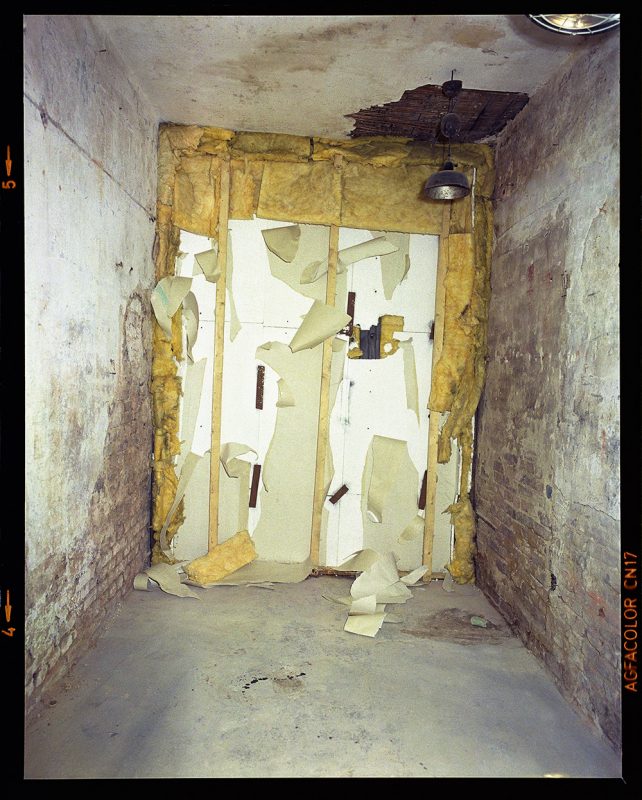

3. Zoe Leonard, Al río / To the River

Hatje Cantz

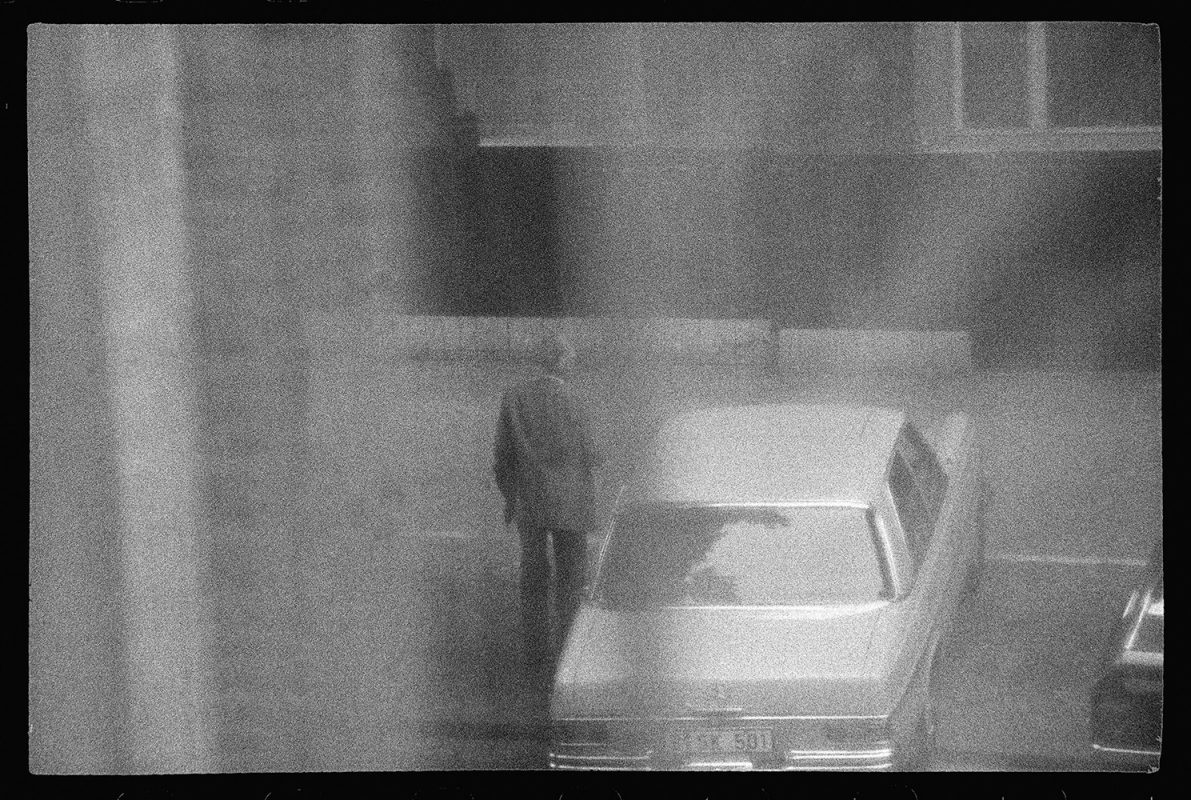

Intended as a companion, rather than a catalogue, to its coinciding exhibitions at Mudam Luxembourg and the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, Zoe Leonard’s Al río / To the River is a real tour de force and totally befitting of this most ambitious body of work. Comprised of 2,000 kilometres worth of photographs, the first volume follows the Rio Grande / Río Bravo along the US-Mexico border through a nuanced weave of abstractions of whirling water, iPhone shots of digital surveillance imagery and documents of Leonard’s own path. Countering the mass media’s sensationalist portrayals of a natural river that is made to perform a political task, all the while exposing the topographical indistinguishability of its demarcations, Leonard’s “half-pictures” inconspicuously shift through different ground-level vantage points, geographical times, tempos and tones. The arrangements of photographs – alternating between standalones to groups of two, four or more – invoke a multiplicity that is perfectly reverberated in the second volume, wherein writers, artists and other thinkers ruminate on the fraught history of the river from their respective fields. The book is an anti-monument, developed through its repetitions and refractions: its emphasis instead is on subjectivity and embodiment; on the notion that taking a photograph is taking a position. After all, Leonard’s preserved black frames do not carry the weight of the world, but the weight of her vision, which in turn becomes ours.

4. Kikuji Kawada, Vortex

Akaaka

Evidence of Kikuji Kawada’s ability to make a masterful book has increased spectacularly with his aptly-titled tome. There are clearly elements of his great opus The Map (1965) contained within the DNA of Vortex, not least for the cover’s chilling allusions to the scars of war left on urban environs. Yet, Kawada’s extractions of the zeitgeist carved into the depths of Tokyo have taken on a fundamentally twisted form here, resulting in surely one of the most bewildering books in some time. Spending time in its company is an intense experience; with extraordinary energy and stamina, the claustrophobic, seemingly never-ending full-bleeds, packed with immense colours, contrasts and textures, plunge us into a strange catastrophe. Pulled predominantly from his vast Instagram archive – which, as curator Pauline Vermare notes in her accompanying essay “Everything was Beautiful and Nothing Hurt”, feels like a “timeless conversation with a man of outstanding depth, soul and modernity” – Kawada’s visions have been augmented on matte paper, thereby summoning the impression of coming into contact with another’s memories – or indeed nightmares. The book feels like, in many ways, a culmination of Kawada’s lifelong mental-mapping, through which he has strived to find the “clues to the future and the whereabouts of my spirit.” Yet, one also feels his quest into the darkness of a sky from which the sun has fallen is but over yet.

5. Nan Goldin, This Will Not End Well

Steidl / Moderna Museet

There are few experiences as ecstatic as encountering a Nan Goldin slideshow in its intended form. With that said, since her breakthrough The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1985), Goldin has produced several books-on-films which have both eschewed and embraced the artist’s original vision for her slideshows. This Will Not End Well is a stunning culmination of all of them, and the first time we can truly appreciate, in one place, the breadth and depth of her work as a filmmaker. The book’s exquisitely-paced sequences are true to their sources; flickering glimpses of light, sinking deeper into the night. Whilst its filmic debt is obviously strong, the black spaces of the pages also remind us that Goldin’s slideshows are, too, films made out of stills. The statis of each frame is heightened here on the page, the result being a reinforcement of the artist’s use of photography as memoir, as preservation, as a talisman against loss. And now, in place of the soundtracks, one hears whirring, whistling and voices. They are different voices, all telling the same story: of passages in and out of addiction; of families lost and found; of romantic obsession until death. There is much pain and heartache to be found here – but also, when it is most needed, love, tenderness and strength.

6. Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, Byker

Dewi Lewis

Dewi Lewis’ republishing of Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen’s Byker (1983), a very distinct and authentic snapshot of British cultural life during the 1970s, feels timely in this moment of heightened social inequality and reflection. It is of course a testament to the incredible depth and power of this body of work, which documents the Finish photographer’s deeply-lived encounters with the terraced, working-class suburb of Newcastle; it was amongst the steep cobbled streets and smoking chimney pots that Konttinen found home. Whilst Byker was destined for redevelopment and eventually bulldozed (along with Konttinen’s own house) to make way for the Byker Wall estate, the photographs do not actively court the reader’s sentimental responses. Instead, they bear an intensity of living and loving, of struggle, resilience and, above all, community. The photographs have been handled with tremendous respect, exemplarily reproduced in tritones and re-sequenced alongside local anecdotes, many of which are published for the first time. Although Konttinen’s introductory text yields wonderful insightfulness, sensitivity and wit, it is her eye that exhibits the greatest empathy. It is perhaps an empathy that only photography, with its ability to, even decades later, relay and multiply a human consciousness, could elicit.

7. Sayuri Ichida, Absentee

the(M) éditions / IBASHO

Looking for the ties that connect the photographs contained within Sayuri Ichida’s Absentee is like groping for Ariadne’s mythical thread, until one realises that the seeking is essentially its point. Though oftentimes elaborate, the book does not feel overproduced or too precious; it is a consummate piece of bookmaking, ranking amongst the finest and most memorable of the collaborations between the(M) éditions and IBASHO. Ichida has reworked the traditional category of elegy (in this case, in honour of her mother) to impressive effect, inviting a variety of viewpoints which can only be gained through act – or process – of feeling. Feather-light in one’s palm, the book is comprised of multiple Japanese bound gatefolds that house four-image sequences. They reveal urban structures, scenes from nature and Ichida’s own body, inverted in silver inks on black matte paper, eliciting an elemental, even ritualistic, experience. For all of Ichida’s emphasis on touch and surface, the book’s dualities – between positive and negative, exteriority and interiority – seem to constantly point, in a very visceral way, to something much deeper. In the strange, tense symmetries of worlds Ichida has sketched, what really comes through is the power of their being in a book: frail but immovable.

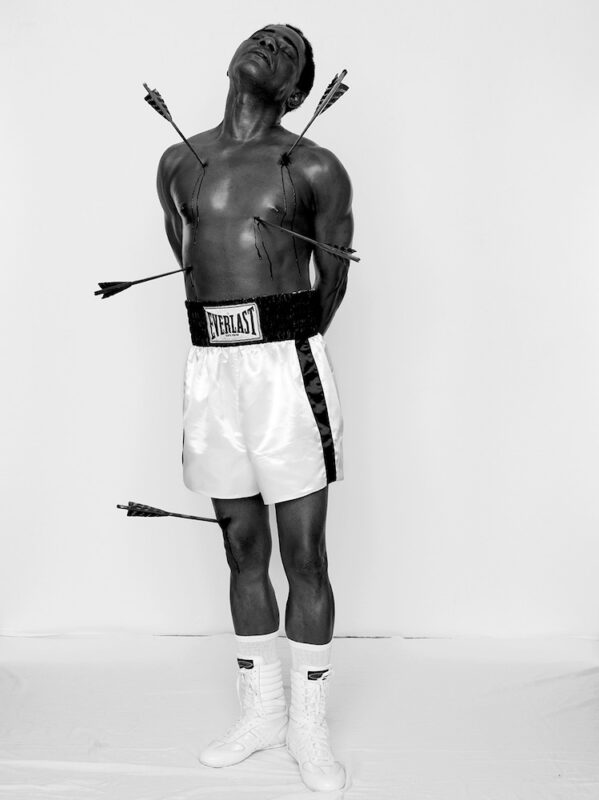

8. Samuel Fosso, African Spirits

Sébastien Girard

The latest gem to emerge from the printing workshop of Sébastien Girard is African Spirits by Samuel Fosso, a most enigmatic artist who, since his early experimentations in performative self-portraiture in his Bangui studio in the 1970s, has never stood still. Although it is, in design terms, a comparatively restrained follow-up to the dashing Studio Photo Nationale (2021), Girard’s decision to print Fosso’s legendary series as a newspaper-format risograph publication is characteristically wise, for here is a work concerned with the media, celebrity and the history of representation. Fosso references and restages (or moreover parodies) famous photographs – including mugshots, press images and studio portraits – of prominent personalities of 20th century Black liberation movements, the most iconic of which is Carl Fischer’s 1968 Esquire cover showing Muhammad Ali impaled by arrows, martyred as St. Sebastian. We also find Fosso self-styled as Aimé Césaire and Léopold Sédar Senghor, two principal thinkers of Négritude. Indeed, the posture of revolt – a voice of raising up, a voice of freedom, a voice for the retrieved spirit – propels these performances. What’s more, through his extension of photography’s role in the construction of myths – this book only the latest chapter – Fosso reminds us that what’s past is always prologue.

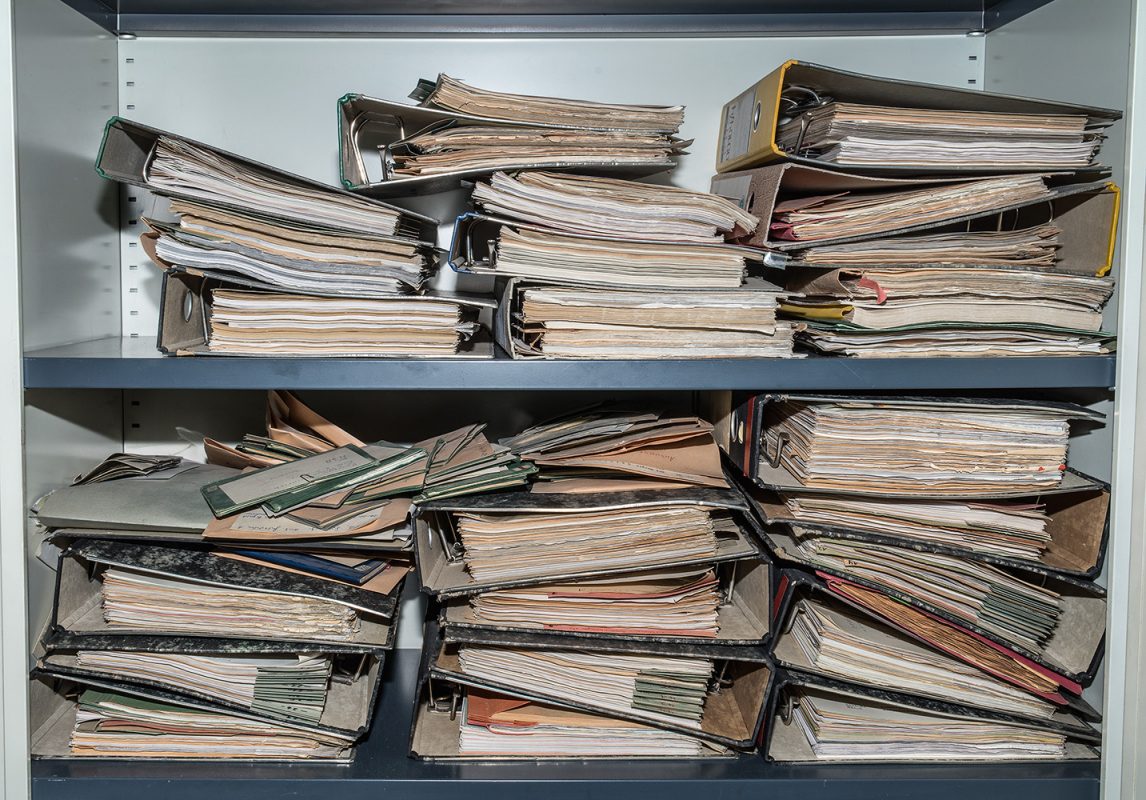

9. JH Engström, The Frame

Pierre von Kleist

Believing in man today is complicated; what is left to admire, desire or envy? There has been no shortage of meditations on masculinity in recent years, but JH Engström’s, which is entitled The Frame, stands out for its scope and sincerity. The daunting exterior of this black, almost bible-like, book belies what lies inside: three-decades-worth of portraits of the men in Engström’s life; trans and cis, naked and bruised, desperate and vulnerable, sometimes violent but never fantasy (someone else’s, theirs, his). Divided into roughly-edged chapters, which either begin or end with a portrait of the artist himself, the rhythmic sequencing is, whilst skilfully sustained and indeed thematised, totally unconcerned with the language or logic of a single, sovereign gender. On the contrary, these broken faces find themselves mirrored by the frost-shattered, ice-aged rocks of Engström’s native region of Värmland in Sweden, which bracket – or frame – this book, which is really more like a refracted self-portrait. The effect is startlingly existential. What Engström invites us to find is the anima within. This is, after all, what makes us human.

10. Meghann Riepenhoff, Ice

Radius Books / Yossi Milo

Volatility, tactility, mercurial, the sublime: these are the words that come to mind when perusing Meghann Riepenhoff’s exquisite Ice. Although it is delivered with an immaculate blind debossed cover bearing frosted imprints, the imagery within is anything but. By producing cyanotypes through an unpredictable process of physically tracing ice – in varied temperature degrees, water types and crystalline structures – onto photographic paper, Riepenhoff has clearly conducted herself with great integrity, putting herself at the mercy of natural forces in an era when human urges to contain the environment have caused unprecedented destruction to our planet. Because her prints are left unfixed – in a state of flux from the point of their conception – their being reproduced on the page naturally limits their inherent drama. Nevertheless, it is by way of the book’s cumulative effect that Riepenhoff successfully evokes the fluidity in the frozen. These are the words which title the beautiful text by Rebecca Solnit, who writes: ‘… there was the yearning of blue, which is itself the colour of yearning because it is the colour of distant things…’ Riepenhoff reminds us that they are also the blues that kicked off the photobook in 1843: the blues of Anna Atkins. How wonderful it is to see her legacy live on in such spellbinding ways.♦

—

Alex Merola is Assistant Editor at 1000 Words.

Images:

1-Cover of Carmen Winant, Arrangements (Self Publish, Be Happy/Images Vevey, 2022). Courtesy the artist, Self Publish, Be Happy and Images Vevey.

2-Tearsheet from Carmen Winant, Arrangements (Self Publish, Be Happy/Images Vevey, 2022). Courtesy the artist, Self Publish, Be Happy and Images Vevey.

3-‘Mattias. Study for The Night Porter (1974)’ from Collier Schorr, August (MACK, 2022). Courtesy the artist and MACK.

4-Detail from Zoe Leonard, Al río / To the River (Hatje Cantz, 2022). Courtesy the artist, Galerie Gisela Capitain and Hauser & Wirth.

5-From Kikuji Kawada, Vortex (Akaaka, 2022). Courtesy the artist and Akaaka.

6-From ‘The Other Side’ (1992–2021) in Nan Goldin, This Will Not End Well (Steidl/Moderna Museet, 2022). Courtesy the artist, Steidl and Moderna Museet.

7-‘Kids with Collected Junk Near Byker Bridge, Byker’ (1971) from Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, Byker (Dewi Lewis, 2022). Courtesy the artist and Dewi Lewis.

8-‘#207’ (2021) from Sayuri Ichida, Absentee (the(M) éditions/IBASHO, 2022). Courtesy the artist, the(M) éditions and IBASHO.

9-‘Self-Portrait (Muhammad Ali)’ (2008) from Samuel Fosso, African Spirits (Sébastien Girard, 2022). Courtesy the artist and Sébastien Girard.

10-From JH Engström, The Frame (Pierre von Kleist, 2022). Courtesy the artist and Galerie Jean-Kenta Gauthier.

11-From Meghann Riepenhoff, Ice (Radius Books/Yossi Milo, 2022). Courtesy the artist, Radius Books and Yossi Milo.