Brea Souders

Vistas

Essay by Alessandro Merola

What will be left for us to probe? What ‘aesthetic entrances’ will be used? Alessandro Merola on Brea Souders’ weaving of pixels and pigments that offers intricate yet epic articulations of the natural world, continuing long traditions of American landscape photography.

The counter-mapping of Michael Wolf, Doug Rickard and Jon Rafman – armchair street photographers who arrived following the inception of Google Street View in 2007 – was distinctly radical at the point of emergence. They mined data captured by roving robot cameras to uncover the forgotten, harrowing and sometimes sublime. Yet, given our urge to seek out the unchartered and unseen, have the possibilities of such appropriations been exhausted? After all, as Philip Larkin ventured: ‘All streets in time are visited’ (1961). So entered Google Photo Sphere in 2013. The software enables users to take 360-degree panoramas deep in the wild, where there are no roads, utilising AI to stitch together hundreds of images and construct navigable constellations. Whilst Rafman even trawled Street View to discover parallel histories of the medium – with one screenshot a repeat of Garry Winogrand’s ‘Los Angeles, California’ (1969) – users of Photo Sphere can contribute to the world of images by rendering a slice of earth for the first time ever.

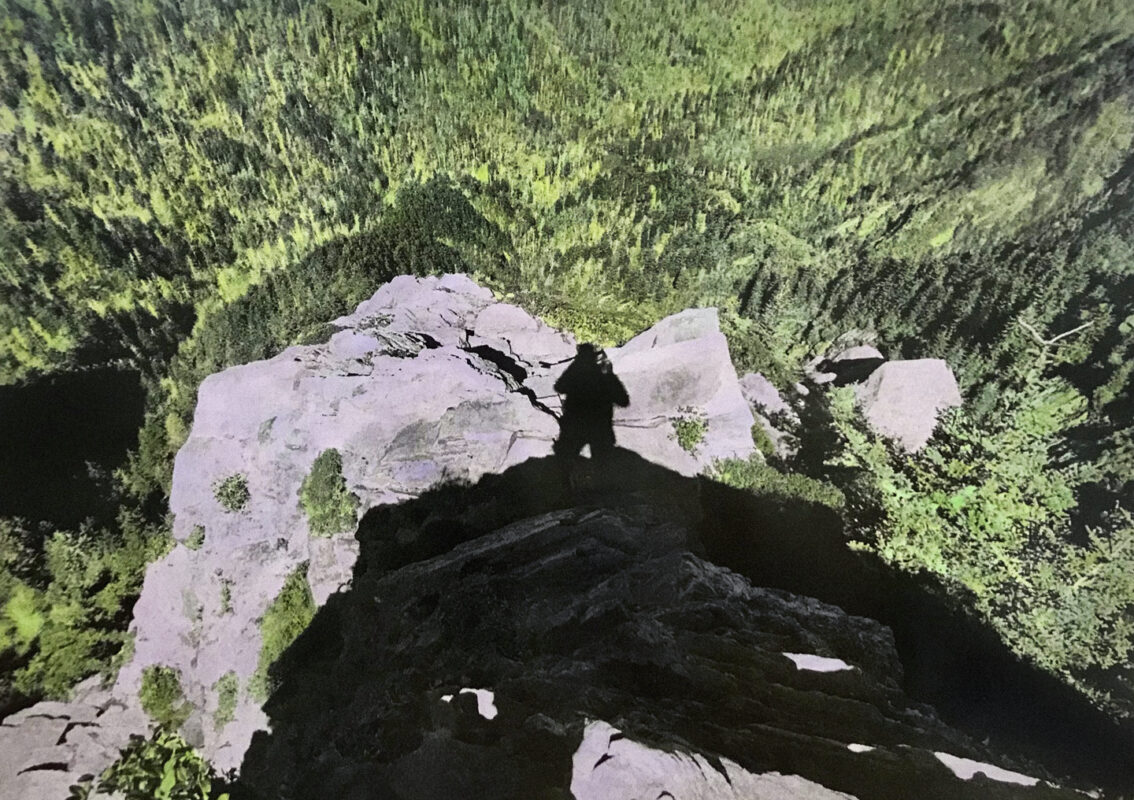

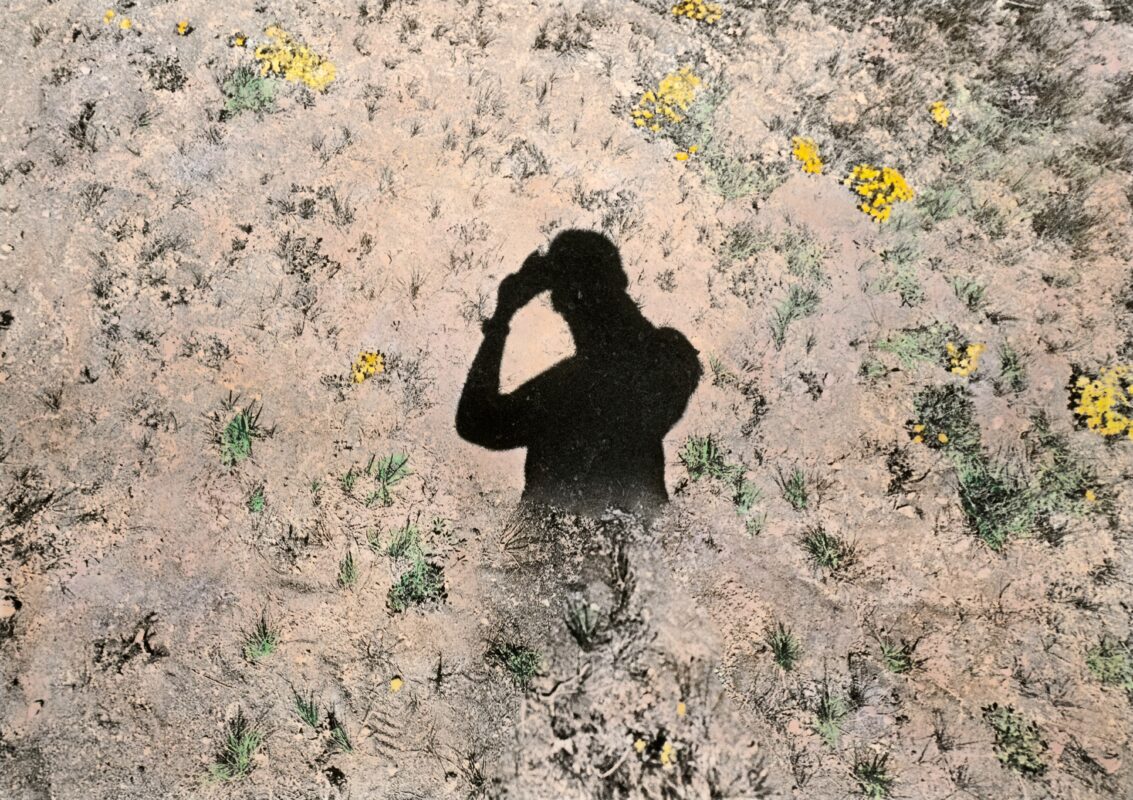

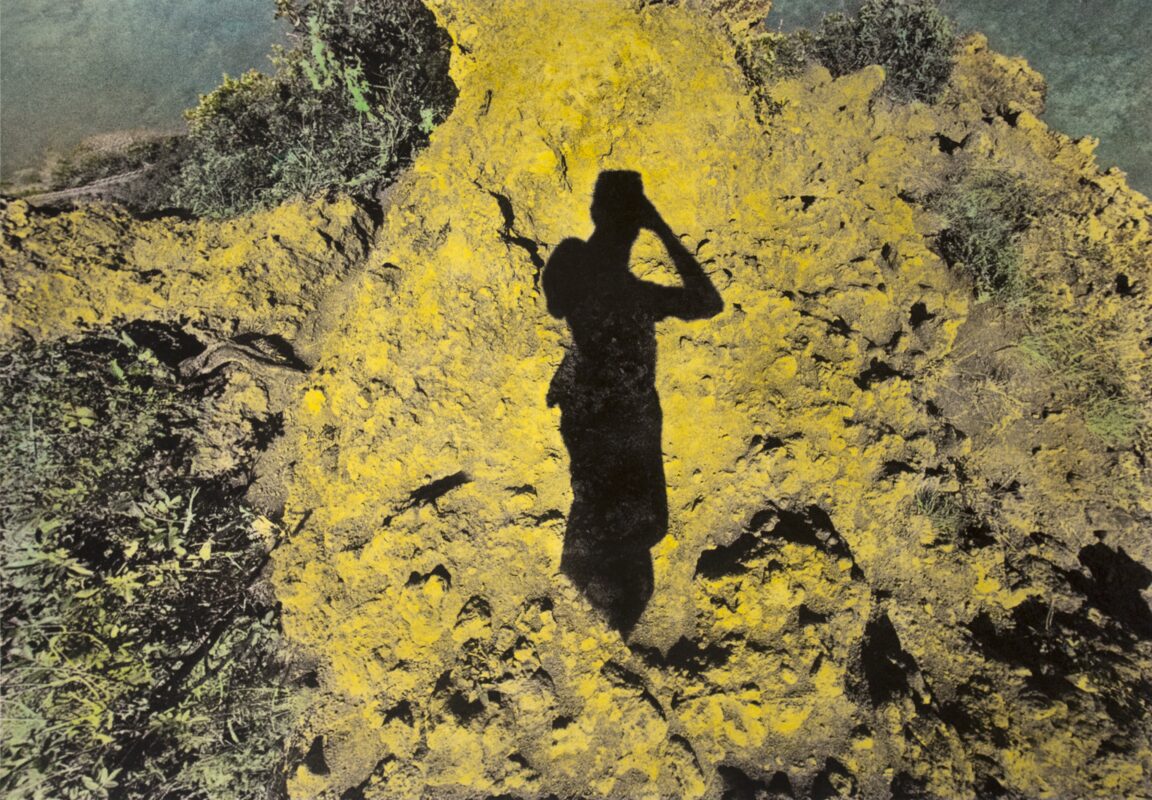

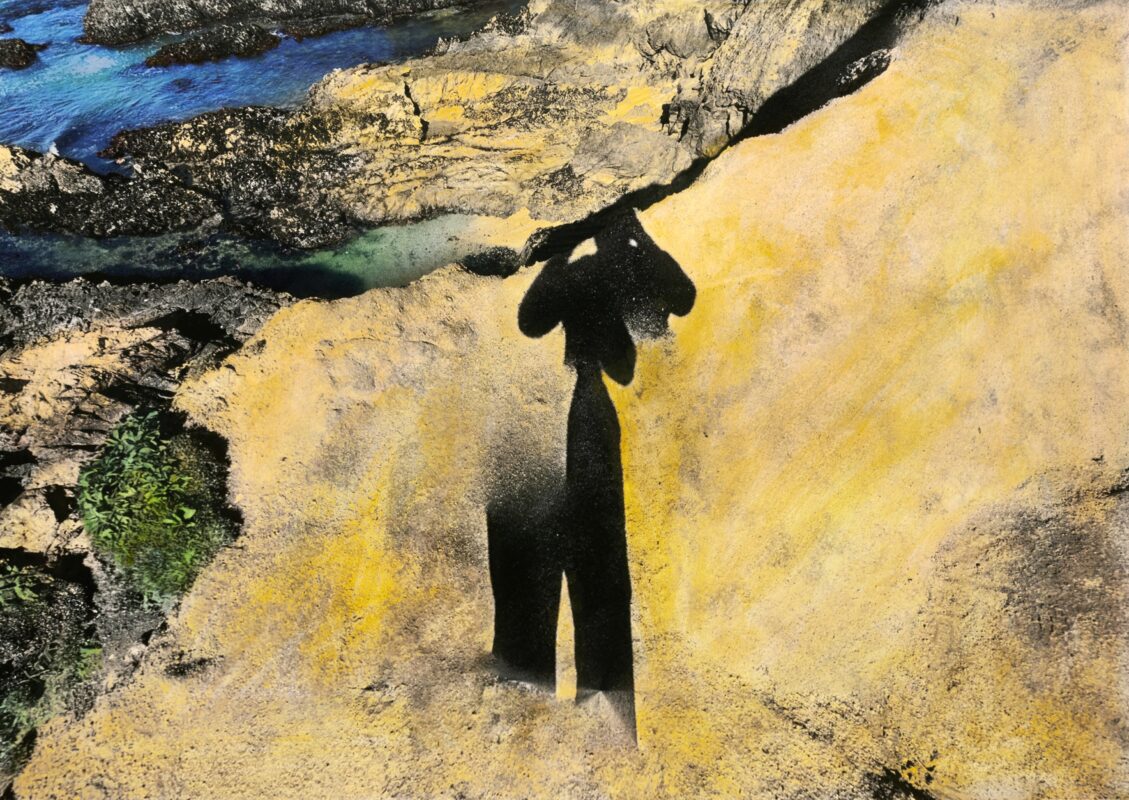

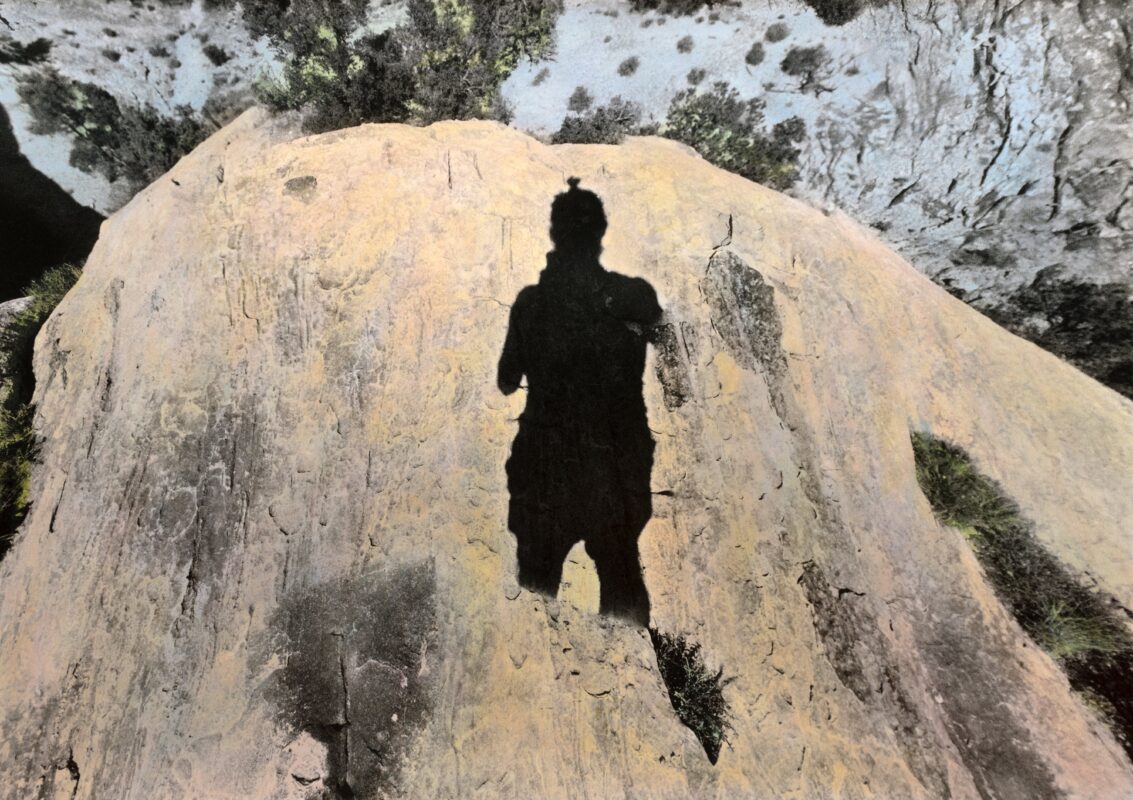

Of the many quandaries such technologies have tabled for photography, one looms on the horizon most existentially: once we reach Jorge Luis Borges’ vision of a map so vast and detailed that it becomes indistinguishable from the empire itself, what will be left to probe? As an artist exploring the limits and possibilities of the medium, Brea Souders has channelled this conundrum into an inspired new work, currently exhibited at Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York. Comprised of images culled from Photo Sphere’s reconstructions of the American West, Vistas stages a geology of ghosts; of shadows sheared from their real bodies. The latter have been erased by Google in a concession to privacy, but the silhouettes – often truncated, splintered and smashed in uneasy syncs – remain, with the algorithm not recognising them as humans. Indicative of her adventitious practice, Souders has shaped these artefacts through an arduous process, circumventing the algorithm’s asperities by painting over screenshots with watercolours. It’s an exercise rooted in late 19th century traditions of colouring, by hand or through printing, souvenir postcards presenting national parks in the West. They allowed Americans to see the utopias they could not visit; ‘aesthetic entrance[s]’ through the picture frame, as geographer Denis Cosgrove has noted,[i] which have only intensified in the intervening years.

The renaissance of image-manipulation – as well as collecting, reproducing and distributing online – has often turned images into degenerate imitations, orbiting miles away from their origins. Hito Steyerl posited: ‘The poor image is a copy in motion. […] As it accelerates, it deteriorates. It is a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed.’[ii] Such disassociations are especially manifest in our encounters with images of the earth, considering that as our assimilation into virtual space becomes more entrenched, our relationship to physical space becomes more estranged. Swooping down on oil fields and feedlots (2012–13) via Google Earth, Mishka Henner conveyed this most saliently. His beautifully abstract composites, enhanced and blown-up, belied the atrocities they depicted, consequently exposing the ways we are increasingly conditioned to witness the world at a surveillance camera’s remove.

Yet, can image-manipulation – digital or analogue – also be a means to bridge the gulf between the viewer, photographic original and place portrayed? Souders’ devoted brushworking of each nook and cranny transmits a venting of nostalgia and homesickness so fiercely felt that these locales – some of which have been reconfigured by fires and mudslides since their uploads – become either impossibly intimate or devastatingly remote. There are instances when Souders moves from pale, pastel hues to produce more retinally-dazzling displays akin to a sun-stroked trance, thereby subverting her predecessors’ primary logic for painting postcards: to make black-and-white more real. Stones swirl luminous yellow; shrubs glow neon green; and mountains ache with a melancholy blue, the same shade Rebecca Solnit called ‘the farthest reaches of the places where you see for miles, the blue of distance.’[iii] Souders seeks to kindle a tactility with these faraway fragments; to commune with the longed-for original. After all, what is desire if not endless distances?

The spectacular mysticism of Souders’ visions invokes an inalienable subjectivity, yet one which is not only steeped in the drama of the self, but bound by a larger awareness of its passage through certain photographic traditions. For, virtually mediating, and appropriating images of, terrains initially imaged by men – Carleton Watkins, Timothy O’Sullivan et al – the artist activates an agency historically withheld from women. Vistas thus becomes all the more disruptive by way of the fact many of its scenes relay female viewpoints; those of women trekking, documenting, mapping and populating. Their imprints recall those of Ana Mendieta’s Silhueta (1973–78), which saw her burn, carve and mould her form into the landscape to ‘return to the maternal source’.[iv] Whilst Mendieta’s interventions were inherently fleeting – the frames of her figure were filled with flowers, blood and candles, all unguarded against a gust of wind or incoming tide – the very act of their documentation ensured the performative pieces endured within an arc of photographic history. Similarly, what Souders has excavated on Photo Sphere are evasions of the ephemeral; traces of traces of the body, ‘stenciled off the real, like a footprint or a death mask’.[v] But what if the Internet itself is not immune from decomposition? In weaving pixels and pigments, Souders secures the survival of each shadow self within imaginary, symbolic and ultimately material registers. Her literal layering of experiences – encounters with and yearnings for the sublime – amounts to an intricate yet epic articulation of the multivalent meanings we can ascribe to the land.

Overcoming loss by ‘fixing a shadow’, the ‘most transitory of things’, is tied up with the advent of photography.[vi] In The Pencil of Nature (1844), William Henry Fox Talbot of course recounted that it was through his fruitless attempts to trace Lake Como’s refracted image in the camera obscura with a pencil that the idea of the photogram occurred. Given human proclivities to orient the self within the world (the oldest known paintings comprise outlines of hands splayed across cave walls in northern Spain), it was only inevitable that the creator’s shadow would enter the frame via the “shadow selfie”. Lewis Hine’s ‘John Howell, an Indianapolis newsboy’ (1908) pictured as much of his figure and tripod as its “subject”, whilst Alfred Stieglitz’s ‘Shadows in Lake’ (1916) echoed Narcissus’ projective stare. With Vistas, however, it is impossible to discern, in the source images themselves, the strategic shadows from the inadvertent ones. Indeed, these photographers were not responsible for an imperfect algorithm that only partially-excised them, nor were they ever able to escape the West’s radiant rays. A less ambiguous consideration is perhaps of that which moved them to pull out their phones in the first place; the mantra of the Instagram era, “pics or it didn’t happen”, looming large.

There are several occasions when Photo Sphere’s algorithm comes, via chance, perilously close to eliminating the human trace in its totality, leaving behind only the shadows of dismembered hands holding onto phones. Maintained in monochrome, four are arranged in a grid layout, constituting the series’ cynosure. They are the eeriest of the images, but equally evocative. For herein lies the alleged democratic virtue essential to photography, as discovered by Talbot at Lacock Abbey: all is illustrated by reversible patches of light and dark. What, then, is the difference between bodies and shadows? I was here, imparts each vista. Gazing into the iridescent blacks of these silhouettes, it is possible to meet ourselves – wanderers, cowboys, pioneers, goddesses, custodians – stood on a cliff-edge somewhere with a wildness in our bones, the sun soaring above and phones pointed ahead, ready to make history and impart back: We were there, too.♦

All images courtesy the artist and Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York © Brea Souders

Installation views of Vistas at Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York until 20 August 2021. Photographs by Olympia Shannon

—

Alessandro Merola is Assistant Editor at 1000 Words.

References:

[i] Denis Cosgrove, “Prospect, Perspective and the Evolution of the Landscape Idea” in Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 10, no. 1 (1985), p. 55.

[ii] Hito Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image” in e-flux #10 (2009), available at e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image, accessed 22 July 2021.

[iii] Rebecca Solnit, “The Blue of Distance” in A Field Guide to Getting Lost (New York: Viking, 2005), p. 29.

[iv] Ana Mendieta, quoted in Ana Mendieta: A Retrospective, eds. Petra Barreras del Rio and John Perreault (New York: New Museum, 1988), p. 10.

[v] Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Doubleday, 1990), p. 154.

[vi] William Henry Fox Talbot, “Some Account of the Art of Photogenic Drawing, or the Process by which Natural Objects may be Made to Delineate Themselves without the Aid of the Artist’s Pencil” (1839), p. 6, available at blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/foxtalbot/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/02/somecccount-booklet.pdf, accessed 22 July 2021.