Top 10

Photobooks of 2020

Selected by 1000 Words

An annual tribute to some of the exceptional photobook releases from the tumultuous year that was 2020 – selected by 1000 Words.

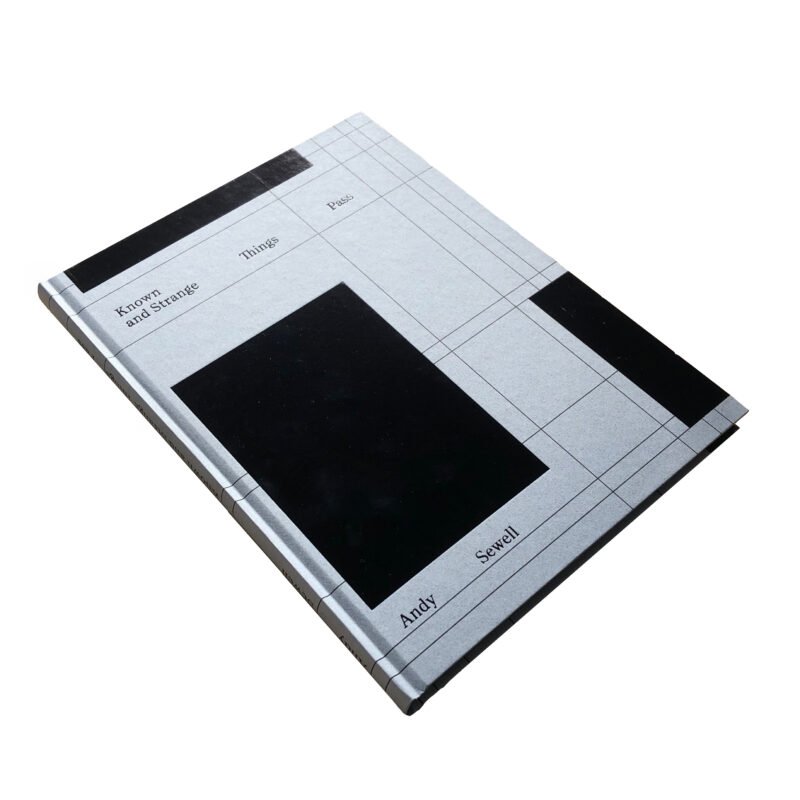

1. Andy Sewell, Known and Strange Things Pass

Skinnerboox

Readers of 1000 Words will recall last year’s feature on Known and Strange Things Pass. Now published in book form by Skinnerboox, Andy Sewell’s meditation on the complex entanglement between technology and contemporary life seems more apposite than ever given the socially-distanced times in which we exist – not to mention the illusory propinquity of screen-based connection. Within a kinetic, non-linear sequence of images that aptly push and pull, ebb and flow, cables – carries of immeasurable quantities of data – weave across the Atlantic Ocean’s bed, and resurface on either side in alien concrete facilities; so rarely seen, these are the material infrastructures that both literally and metaphorically underpin our hyper-connected world. Ambitious, understated and fleeting, Known and Strange Things Pass explores the ways in which the ocean and the Internet speak to each other and speak to us, whilst probing photography’s ability to render visible such unknowable entities, infinitely vaster than we are.

2. Poulomi Basu, Centralia

Dewi Lewis

It has been quite the year for Poulomi Basu, whose docu-fictional book Centralia has earnt the artist the Rencontres d’Arles Louis Roederer Discovery Award Jury Prize, and a place on the shortlist for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2021. Beneath its blood-red, sandpaper-rough cover, Basu takes us through the dense jungles of central India, where a brutal war between the Indian state and Maoist insurgents over land and resources has waged for fifty years, in turn casting light on the woefully-underreported horrors of environmental degradation, indigenous and female rights violations and the state’s suppression of voices of resistance. Embracing a disorientating amalgam of staged photography, crime scenes, police records and first-person testimonies – all punctuated by horizontally-cut pages and loose documents – Centralia traces the contours of a conflict in which half-truths reign over facts. Though not for the faint-hearted, this open-ended account of an ongoing war affords us space to reflect on what we have seen, and to choose what we believe.

3. Buck Ellison, Living Trust

Loose Joints

A worthy winner in the First PhotoBook category for the 2020 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation Awards, Buck Ellison’s Living Trust, published by Loose Joints, requires us to study the visual iconography of privilege as embodied by white, upper-middle class lives – or W.A.S.P. – in the United States. In these carefully constructed and performative photographs, insignia such as wooden cheeseboards, organic vegetables, acupuncture bruises, car stickers, lacrosse gear and even family Christmas card portraits examine how whiteness is exhibited and ultimately sustained through everyday structures, internalised logic and economic prowess. Deftly drawing on the language of advertising and commercial photography, Ellison conjures an uneasy world where the “whiteness project” manifests itself over and over again all the while perpetuating deadly inequality both in material and ideological terms.

4. Antoine d’Agata, VIRUS

Studio Vortex

As the title suggests, this book squares up to our present moment amidst the global health crisis with an unflinching intensity characteristic of the famed Magnum photographer. As soon as Paris entered a lock-down in March, Antoine d’Agata took to the emptied streets with his thermal camera. Here, civilians, medical workers and hospital patients are rendered as spectral, flame-tinged figures that flash across the pages. With temperature the only marker differentiating each pulsating body from the next, d’Agata proffers a haunting yet visceral mood piece laden with an existential dread that is befitting of our times. Beyond the limits of reportage, VIRUS is ultimately borne out of an impulse to get to the heart of things, to make sense of the incomprehensible and to visualise what the naked eye cannot: an invisible enemy, at once everywhere and nowhere. A dystopian masterpiece, these images refuse to be shaken off quickly.

5. Lina Iris Viktor, Some Are Born To Endless Night – Dark Matter

Autograph

Although there is no equivalent experience to witnessing the allure and intricacy of Lina Iris Viktor’s paintings up close, her debut monograph more than makes up for it through its fittingly-regal design. Published to accompany her solo show at Autograph in London earlier in 2020, it takes us into the British-Liberian artist’s singular world, embellished with luminescent golds, ultramarine blues and the deepest of blacks. Drawing from a plethora of representational tropes that range from classical mythology to European portraiture and beyond, Viktor’s practice playfully and provocatively employs her solitary body as a vehicle through which the politics of refusal are staged, and the multivalent notions of blackness – blackness as colour, as material, as socio-political awareness – come to the fore. Some Are Born To Endless Night – Dark Matter is a spelling-binding survey of an artist who is paving the way for new and unruly re-imaginings of black beauty and brilliance.

6. Antoinette de Jong and Robert Knoth, Tree and Soil

Hartmann Books

The intrinsic splendour of the natural world takes centre stage in Antoinette de Jong and Robert Knoth’s first book since their highly-acclaimed Poppy: Trails of Afghan Heroin (2012). Following the Fukushima nuclear disaster of 2011, the Dutch duo set out on a five-year-long project to examine the devastation wrought on the region’s biosphere. Expertly edited by curator Iris Sikking, Tree and Soil combines photographs depicting nature’s reclaiming of the deserted spaces with repurposed material from the archive of German explorer, Philipp Franz von Siebold, which includes a collection of botanical illustrations, animal specimens and woodblock prints amassed during his trips to Dejima, a Dutch trading post, in the early 19th century. The result is an enigmatic yet radical dialogue between two distinct histories – the post-colonial and the post-nuclear, respectively – which speaks of the hubris of humankind and the value of nature, in the process ruminating on the disturbed relationship between the two.

7. Amani Willett, A Parallel Road

Overlapse

Another book of first-rate investment in narrative forms of photography comes from artist Amani Willett. Chronicling the oft-overlooked history of black Americans road-tripping, A Parallel Road deconstructs the time-worn myth of the ‘American road’ as a site in which freedom, self-discovery and, ultimately, whiteness manifests. The book’s direct point of reference is Victor Green’s The Negro Motorist Green Book (1936), a guide which provided newly-roving black road-trippers tips on safe spots to eat, sleep and re-fuel at a time when Jim Crow laws subjected them to heightened oppression, hostility and fear of death. Whilst maintaining the original’s scrapbook details – from hand-held dimensions to sewn binding – Willett has adroitly juxtaposed archival material with photography, media reproductions and Internet screenshots from the present day to lay bare the ongoing realities of systemic racism in the United States. A harrowing yet urgent title in a year in which the dangers posed to black people when out-and-about have been undeniable.

8. Diana Markosian, Santa Barbara

Aperture

In yet another dazzling year for Aperture’s publishing arm, with Justine Kurland’s Girl Pictures and Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph amongst notable releases, perhaps the standout is Diana Markosian’s Santa Barbara. Here, the Armenian-American photographer reimagines her mother’s leap of faith as she abandoned her husband in post-Soviet Russia to start a new life in the United States with her children. Family snapshots, film stills and re-enactments by actors play out alongside a script written by the original screenwriter of the 1980s soap opera Santa Barbara, which, for a generation of regime-weary Russians tuning in through their television sets, embodied the promises of the American dream. For all its experimental edge – rigorously merging fact and fiction – this book retains its deeply intimate take on the themes of migration, memory and personal sacrifice. With the project slated to show at the SFMOMA in early 2021, Markosian’s work continues to enthral audiences.

9. Yukari Chikura, Zaido

Steidl

Also excavating personal histories is Yukari Chikura in this strong contribution to the year’s offerings. Shortly after his sudden passing, Chikura’s father appeared to her from the afterlife, imparting the words: “Go to the village hidden deep in the snow where I lived a long time ago.” Committed to honouring this wish, Chikura embarked on a voyage to the remote, winter-white terrains of north-eastern Japan. The resulting publication documents what she found: Zaido, a good fortune festival dating back to the 8th century. Printed across an exquisite array of papers under the direction of Gerhard Steidl, images imbued with magical realism reveal costumed villagers gathering before shrines and performing sacred dances. Whilst the accompanying ancient map and folkloric parables lend this book an ethnographic feel, there is something more incisive at work too. Intertwining the villagers’ spiritual quests with Chikura’s own journey through the darkness that pervades mourning, Zaido is a tale of collective soul-searching that seamlessly traverses cultures as well as centuries.

10. Raymond Meeks, ciprian honey cathedral

MACK

No annual ‘best of’ book list seems complete without a monograph from skilled book-maker, Raymond Meeks. Characteristically poetic and perceptive, his new release with MACK invites readers into the domestic world shared between he and his wife, Adrianna, during a period in which they were packing up their home. Opening with a flurry of photographs which depict Adrianna asleep, bathing in the soft, early morning light, both the tone of imagery and its rhythms sets forth an experience that is akin to a waking dream. What follows is an intercourse of image and verse that pairs the quiet, quotidian rituals that populate each passing day with topographical observations of a house laid bare: mounted stacks of dishes, cracked walls and overgrown tendrils. Herein lies the melancholic undercurrent which vibrates throughout ciprian honey cathedral, a bittersweet evocation of the things memories cling to, and the things we leave in our wake. ♦

—

Alessandro Merola is Assistant Editor at 1000 Words.

Tim Clark is Editor in Chief at 1000 Words, and a writer, curator and lecturer at The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University. He lives and works in London.