Lisa Oppenheim

Spolia

Exhibition review by Jilke Golbach

In her Spolia exhibition at Huis Marseille, Amsterdam, Lisa Oppenheim boldly addresses the absence left by artworks confiscated or forcibly taken from Jewish owners during the Nazi regime. Utilising innovative photographic techniques, the American multimedia artist conjures the missing items and meticulously details their history. As Jilke Golbach notes, Oppenheim’s profound connection to the archival is palpable, resulting in a visually stark yet conceptually rich body of work.

Jilke Golbach | Exhibition review | 23 May 2024

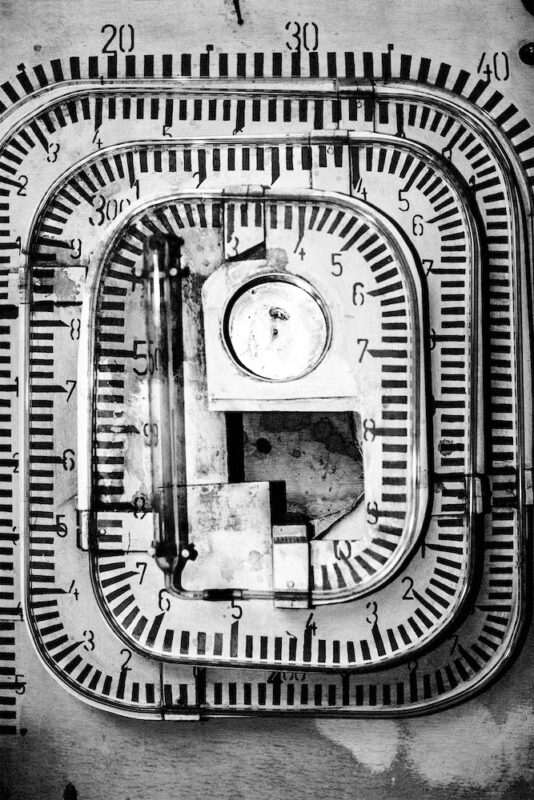

A small globe sits wonkily atop a table crowded with books, papers, and scrolls in one of Lisa Oppenheim’s photographs in Spolia, on display at Huis Marseille, Amsterdam. Its precarious tilt intimates that a fall is about to happen, as if this short moment of suspension might, at any second, be shattered by the orb, smashing into a thousand little pieces. In art history and iconography, globes can signify a number of different things: power, knowledge and vanity. But in this 17th century still life (or rather, its ghostly reproduction), it also appears to carry a more literal meaning. Seen up-close in the gallery, Oppenheim’s inverted image reveals just enough detail for us to see that the globe – a favourite cartographic object of old masters like Johannes Vermeer – is accompanied by other navigational instruments. A compass and a nautical measuring device tell us this picture is one of maritime expedition, a testimony to the period’s absolute obsession with global exploration, trade and imperial domination.

Nature Morte (1943/2022), the little-revealing title of the picture with the globe, could have opened the show, symbolic as it appears to be of a body of work that is, in different ways, all about mapping and navigating, the (re)discovery of things that have been obscured, concealed or dispersed, and the movement of objects across the globe in the aftermath of (neo-)imperialist greed. At a time when restitution debates are at the heart of museum discourses, Spolia – meaning ‘spoils’, or repurposed objects, a Latin term originally employed for the re-use of ancient materials and structures – engages with the very impossibility of restitution, with the loss and absence of objects that will likely never be regained.

In Spolia, Oppenheim ventures into the complex histories of artworks that were confiscated or forcibly removed from Jewish owners during the Nazi regime and have been missing ever since – not to try and retrieve them but to transform their absences into new spectres of being. Through extensive archival research, the American artist follows the trails of these looted objects and uses the inventories, catalogue entries and photographic documentation she finds as the raw material for an experimentation with various techniques of reproduction, among which: the solarisation of gelatin silver prints and the production of textile works, photograms and slide projections. Oppenheim has spoken about this regenerative practice as giving the missing artworks ‘afterlives’, mobilising photography as a method to narrate their stories, their unfinished provenances otherwise.

Oppenheim is at home with the archival. Throughout her practice, she has repurposed, rephotographed, reprocessed and revisited historic imagery to explore the capacities and limitations of the photographic medium, often challenging its (in)ability to function as document, witness or evidence. In Killed Negatives, After Walker Evans (2007), for example, she went in search of the missing pieces from the hole-punched (or ‘killed’) Farm Security Administration photographs of Depression-era rural America – remnants of a ruthless editorial practice that was to prevent the photographs’ further reproduction in the 1930s. In another series, Smoke (2013), she drew on the Imperial War Museum archive in London to create large-scale negatives from aerial photographs of the bombing of Caen, France during the Allied invasion in 1944 by exposing the prints to the light of an open flame. Some of the photographic techniques and questions that run through these bodies of work also resurface in Spolia, where Oppenheim plays with chemicals, light and fabric to spool a web of traces that visualise absence.

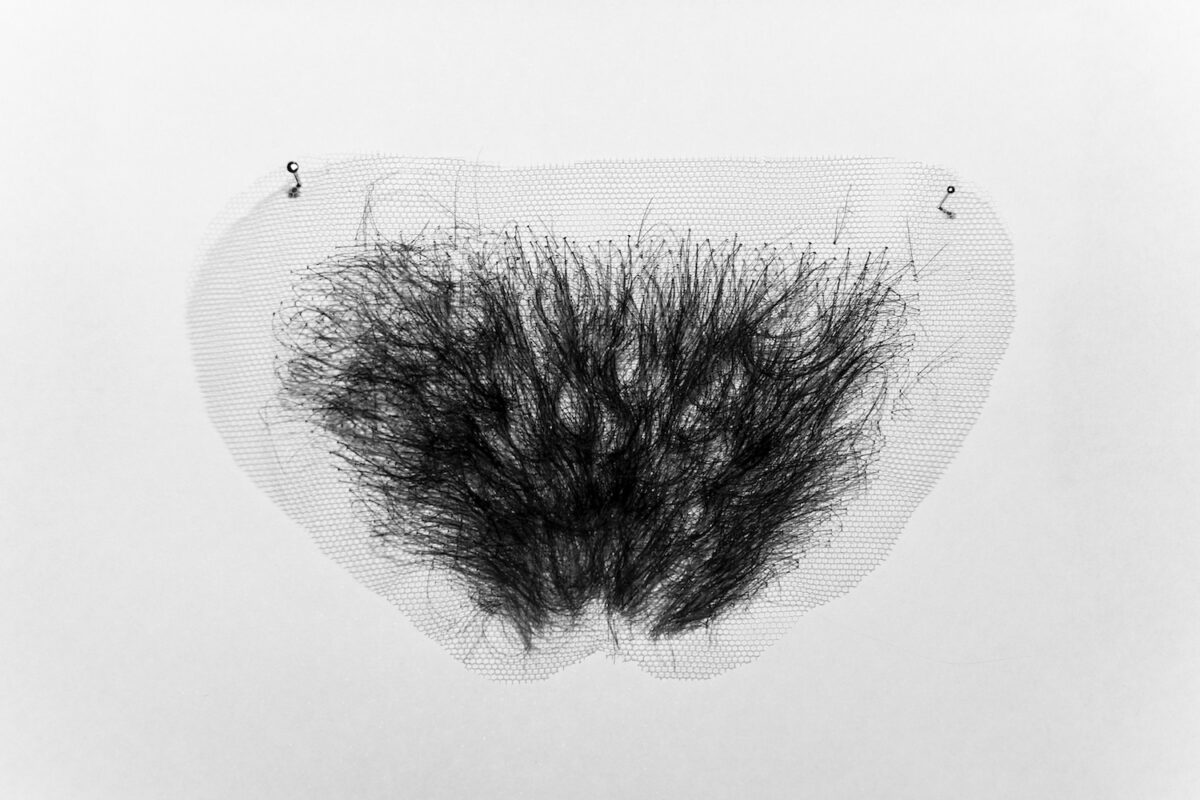

Spolia is a visually austere, conceptually potent body of work. The muted blacks, whites and greys that populate the gallery walls play with the positive and negative photographic image, deliberately absorbing or reflecting the gaze of the viewer. Oppenheim uses the process of solarisation to invert the tones of documentary images, many of which were created through the Nazis’ bureaucratic infrastructure, including at the Jeu de Paume in Paris. The result is unnervingly otherworldly. The individual works – hung alone or in pairs – possess a kind of preternatural beauty (the eye lingers on the exquisite bloom of an ostensibly stemless tulip, or the sharply cut curl of a lemon peel), but Spolia is perhaps at its most striking when the photographs appear in sequences. Beim Spitzenhändler (1943/2024), for example, repeats the woven image of a lacework that was likely destroyed in the last days of WWII in an increasingly opaque transition from light to dark. The act of refashioning the missing piece of framed lace on a Jacquard loom, in which white replaces black one thread at a time, is Oppenheim’s way of reviving an object of which nothing is left but a trace of gelatin and silver.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, Oppenheim overlays photographs of the Paris sky above 38 Avenue Henri Martin with fragments of the painting Miroir entouré d’oiseaux (1650/c.1700) by Jan Davidsz de Heem, one of 334 Dutch and Flemish masters taken from the Schloss family in the early years of the war. The smoke-like effect of the sky over the family’s former home hints at the way nearly half of that collection vanished without a trace. This arresting installation also underlines what a remarkable setting Huis Marseille is for the exhibition; the walls of the monumental canal house built by a French sea merchant in 1665 at the height of the Dutch ‘Golden Age’ of painting evoke a multidirectional homecoming of sorts for the disappeared Netherlandish masters.

Spolia might be read as a series of simultaneously sticky and slippery pictures. The curators at Huis Marseille effusively detail the histories and provenances of the missing artworks, the families they belonged to and the archives that hold their records. Some of these things cling to the images – names, places, dates, biographies, dimensions, associations. Yet, the haunted objects themselves remain almost infuriatingly elusive, just out of sight as much as they are out of reach. The harder one looks, the more any sense of specificity is relegated to fragmentation, an experience that is reinforced by Oppenheim’s gravitation towards the prevalent, visually repetitive genre of still lives and landscape paintings. Perhaps such a sense of disorientation is the point of this subtly profound body of work, in which Oppenheim does not serve up any answers but invites questions about history, memory and temporality, and about the nature of the photographic medium as a mode of (re)mediation. An engagement with these artworks beyond restitution requires navigating, and inhabiting, the positive/negative space of photography.♦

All images courtesy the artist and Huis Marseille, Amsterdam. © Lisa Oppenheim

Spolia runs at Huis Marseille, Amsterdam until 16 June 2024.

—

Jilke Golbach is an independent curator specialising in photography. She was previously Curator of Photographs at the Museum of London. Alongside her curatorial practice, she is completing a PhD project at University College London on the subject of heritage, neoliberal urbanism and the right to the city.

Images:

1-Lisa Oppenheim, Nature Morte, 1943/2022 (Version II), 2022. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles.

2-Lisa Oppenheim, Nature morte à la tulipe, 1637/2023 (Version II), 2023. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles.

3-Lisa Oppenheim, Pendant, 1943/2021, 2021. Courtesy THE EKARD COLLECTION.

4-Lisa Oppenheim, Landschap met Konijnen, n.d./2023 (Version I), 2023. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles.

5-Lisa Oppenheim, Stilleven met roemer, nautilusschelp en roos op een donker kleed, 1645-1655/2023 (Version I), 2023. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles.

6-Lisa Oppenheim, Stilleven met boeken en tekengerei, 1833/2023 (Version II), 2023. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles.