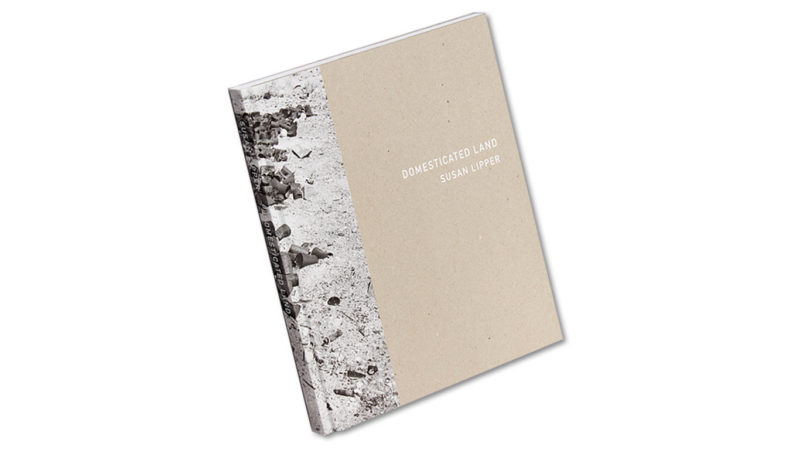

Susan Lipper

Domesticated Land

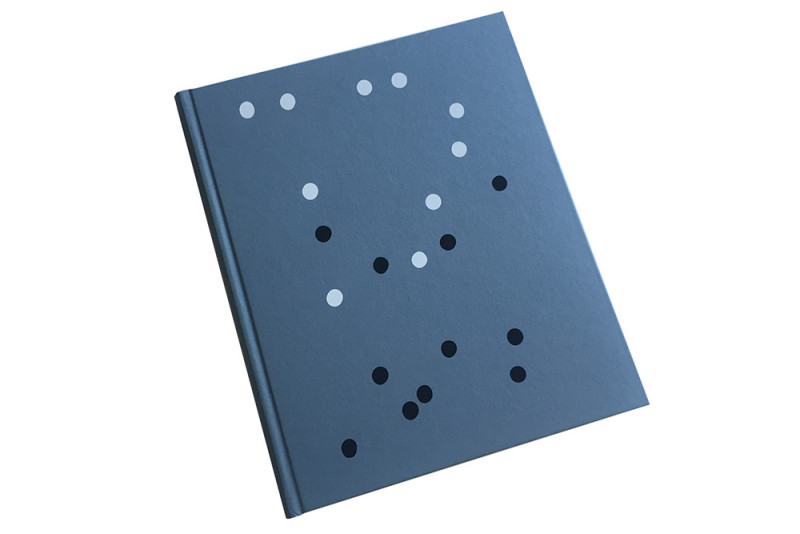

MACK

The female body has always been conflated with visions and narratives of the land. There are all of the same old tropes, of course; that women are intrinsically linked to nature – even governed by it – in a way that men aren’t, and that the mounds and sweeping curves of the landscape mirror those of the female form. Indeed, Susan Lipper’s Domesticated Land opens with an image of sand dunes in the Californian desert that look more than vaguely reminiscent of the female body, but something entirely different is going on here too.

The notion of gendered landscapes is upturned in Lipper’s Land pictures. On the one hand, she shows us images such as one in which a woman lies face down with her head in the dust in front of a black hole that’s opened up in the ground before her, and another where we see the detritus of kitchen goods strewn across the sand (which may be somewhat symbolic of the author’s thoughts on the notion of woman as homemaker). On the other hand, we have the backdrop of the American West – cracked, fractured, historically male-driven terrain in which military bases and operations are nestled, and where countless male writers have famously journeyed in search of themselves. In some of Lipper’s pictures we see army men and tanks and brutalist concrete structures cutting through the landscape. Though personal and artistic journeys through this place are not new, Lipper navigates this land from a personal, female slant, making images that oscillate between document and fiction, and “putting female subjectivity into relief.” The desert as a land of mysticism, self-enlightenment and spiritual opportunity, roamed by healers and medicine men across decades, is probed too and homes appear abandoned, in one image a single serpent writhes in the ground, in others barbed wire snakes through the frame.

Domesticated Land is the third instalment in a trilogy of books for which Lipper spent nearly thirty years travelling the USA from East to West in search of ‘true’ America. Sun-bleached and washed out, Lipper’s black and white vision of the desert transforms it into a sort of stasis, unnervingly quiet, as if everything that was supposed to happen has happened, and now all we can do is wait. People are tiny in most of the photographs, swallowed up by the landscape and often looking outwards, to the sky or the horizon, watching for the arrival of something unknown. From time to time, the words of women punctuate the images. At the very end of the book, an excerpt from Catherine Haun’s 1849 diary A Woman’s Trip Across the Plains talks of an evening spent singing patriotic songs and celebrating the Declaration of Independence with the firing of a gun or two. ‘…three cheers for the United States and California territory in particular!’ it reads. Most potently, Domesticated Land seems to offer a timely sense of foreboding about the current state of America and its politics, and a possible harbinger of things to come. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist and MACK. © Susan Lipper