Julian Stallabrass

Memory of Fire: Images of War and The War of Images

Special book review by James McArdle

“When it comes to understand our own nature as humans the tables are often turned, for a very similar rigid prejudice in favour of high-level (and only high-level) perception turns out to pervade and even define ‘the human condition’.” Douglas Hofstadter

Do we need another book full of images of war and mortal cruelty? Julian Stallabrass leaves the reader in no doubt of this quandary in his new title Memory of Fire: Images of War and the War of Images, published by Photoworks.

It begins with a caveat about how his task as curator of the 2008 Brighton Photo Biennial, from whence the material presented here originally came, was akin to that of the journalist, Vasily Grossman’s story of the Red Army’s jocular propping of frozen German soldiers’ corpses as the soldiers advanced south of Kharkov – insofar as arranging photographs of the dead into something coherent and meaningful. The book then proceeds with an extract from Eduardo Galeano’s Memory of Fire, itself a story of lost history, which serves to remind us of the vital preservative value of the archive, and its vulnerability to destruction or revision. Its inclusion begs the question: should we lose these records of conflict; will history repeat itself without our knowing?

What follows is spreads of provocative war images from professional photographers, military amateurs and artists, some now all-too-familiar, each vividly introducing a chapter of the book including The Power and Impotence of Images; Making an Ugly World Beautiful? Morality and Aesthetics in the Aftermath; and Embedded with Murderers: Balad, Iraq, 15 July, 2003. Images of war and their use as agents of warfare (the war of images) are the two sides of the same coin and, throughout, Stallabrass confronts their corporate and mercenary potential.

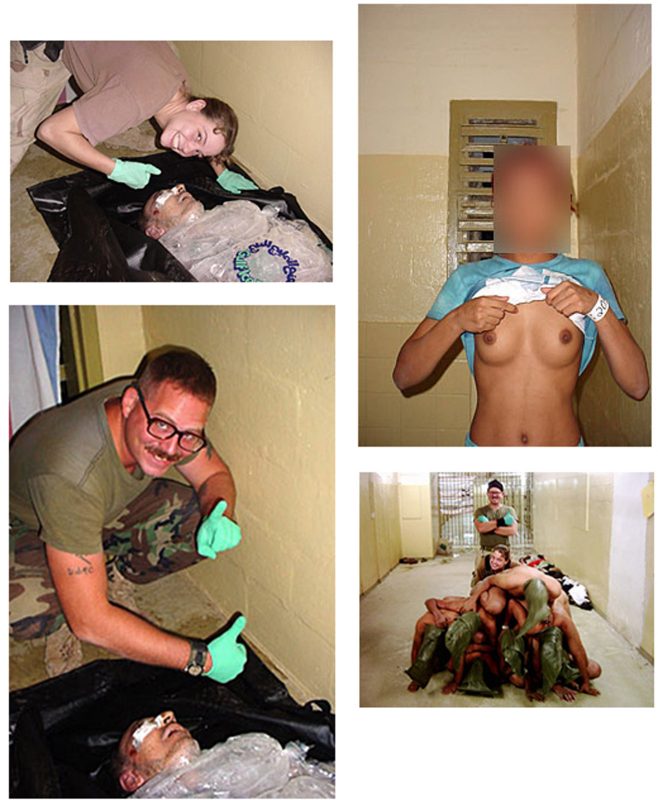

Clearly, the pornography of war is irresistible. There is a masochistic rush in exposing oneself to the images included here; how “gruesome/awesome” (to quote Evan Wright of Rolling Stone Magazine) it is to witness the perennial opening image Abu Ghraib 11.51 pm Nov 7 2003. Cpl Graner and PFC England posed for the picture, which was taken by SPC Harman to be made involuntarily complicit in an act like that described by Grossman? Stallabrass judiciously tackles complexities in the imaging of violence, revealing conflicts between their instrumentality and aesthetics, which he tirelessly wrestled with during the process of curating the Biennial. That same year regrettably saw the passing of Philip Jones Griffiths, whose Vietnam Inc. is one sure instance in which images changed the course of a war. With the aim of scrutinising art, document and ethics in extremis, Stallabrass, asks whether Jones Griffiths oriented Vietnam Inc. while taking the pictures or as prompted by anti-war sentiment, eliciting the arresting reply; “I distrusted them […] suspicious of those weekend, armchair communists!”

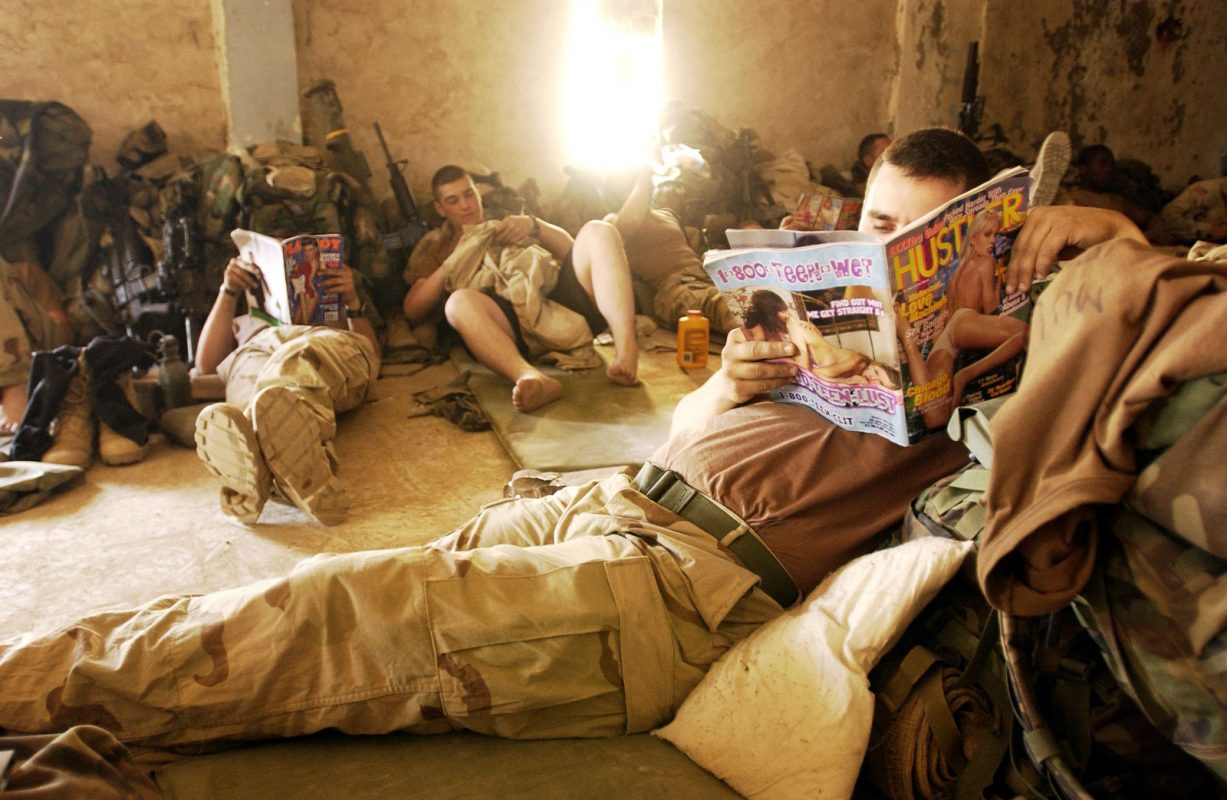

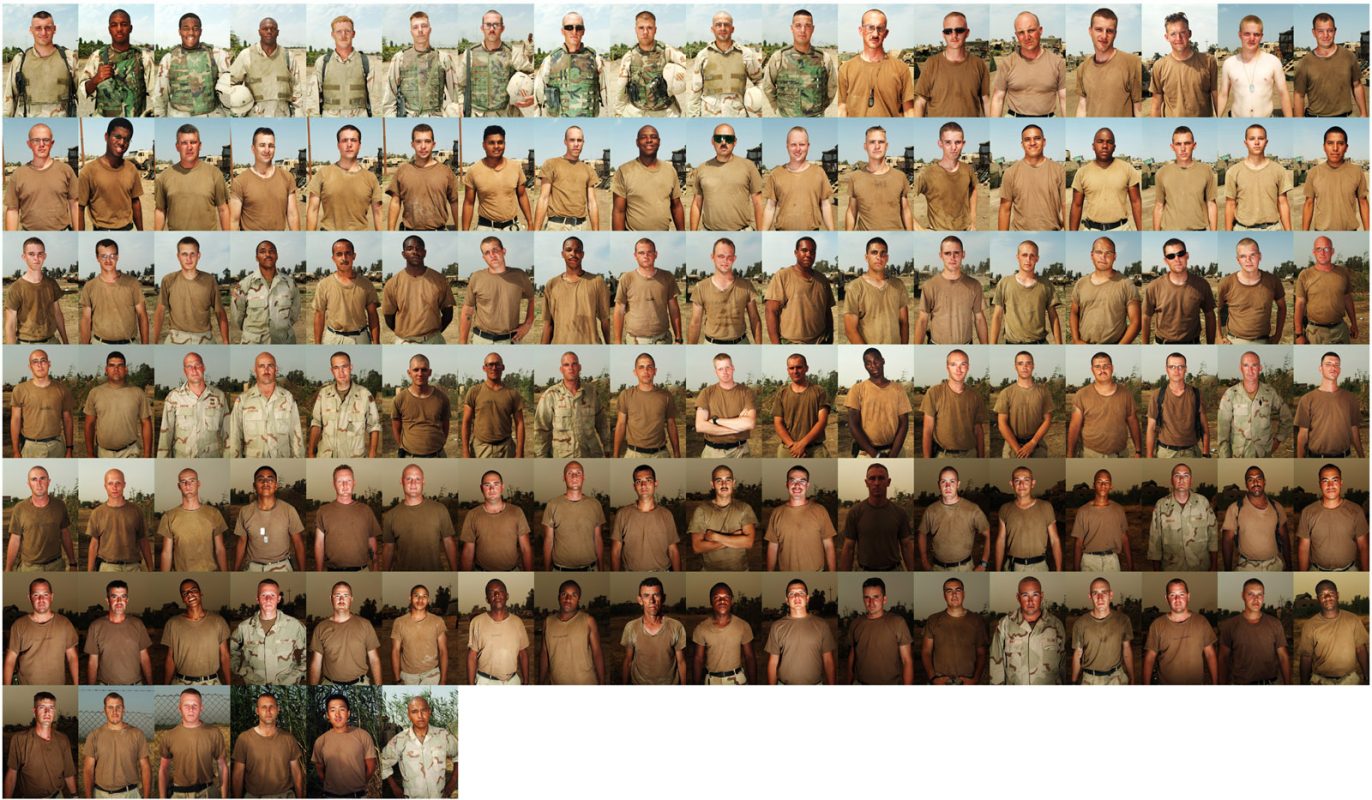

Equally principled or fiercely independent reactions come from Rita Leistner’s and Ashley Gibertson’s frank accounts of the embedded versus the ‘unilateral’ photojournalist bringing deep perplexity over the compromises in either means of accessing a war, alongside insights into the aesthetics of flash or of typological portraits. Most impressive are these photographers’ demonstrations of high-stake, political potentials of relations between soldier, civilian, photographer and audience, and their steadfast belief in honesty despite the changing status of embedded journalists to targets of local anger and the undervaluing, misrepresentation or ignoring of their images by their editors.

At the heart of the book is the consideration of art in representing, rather than documenting, war. Questioning whether “[social] documentary photography is [any] longer…capable of representing today’s technological warfare”, in her essay Sarah James considers the failure or success of a people-less aftermath photography practicing a romanticising aesthetic of the ruin, to summon Adorno’s political sublime. Less equivocal, though more sinister, are Trevor Paglen’s remote imaging of US military-industrial black sites and spy satellites is espionage in an intriguing evidential/aesthetic relationship with heat mirages. Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s acknowledgement of earlier failures to represent any of the traumas of soldiers’ injuries led to their eschewing conventional documentation. In their now notorious series The Day Nobody Died they adopt the conceptual, pragmatic strategy of exposing a roll of photographic paper directly to front line Afghan light and filming British troops, with whom they were embedded, carrying the heavy cardboard box containing it. Stallabrass queries why the resulting prints are portents of destruction, while the video is comic; their response reveals how taking performance and non-figurative art to the theatre of war might be legitimate.

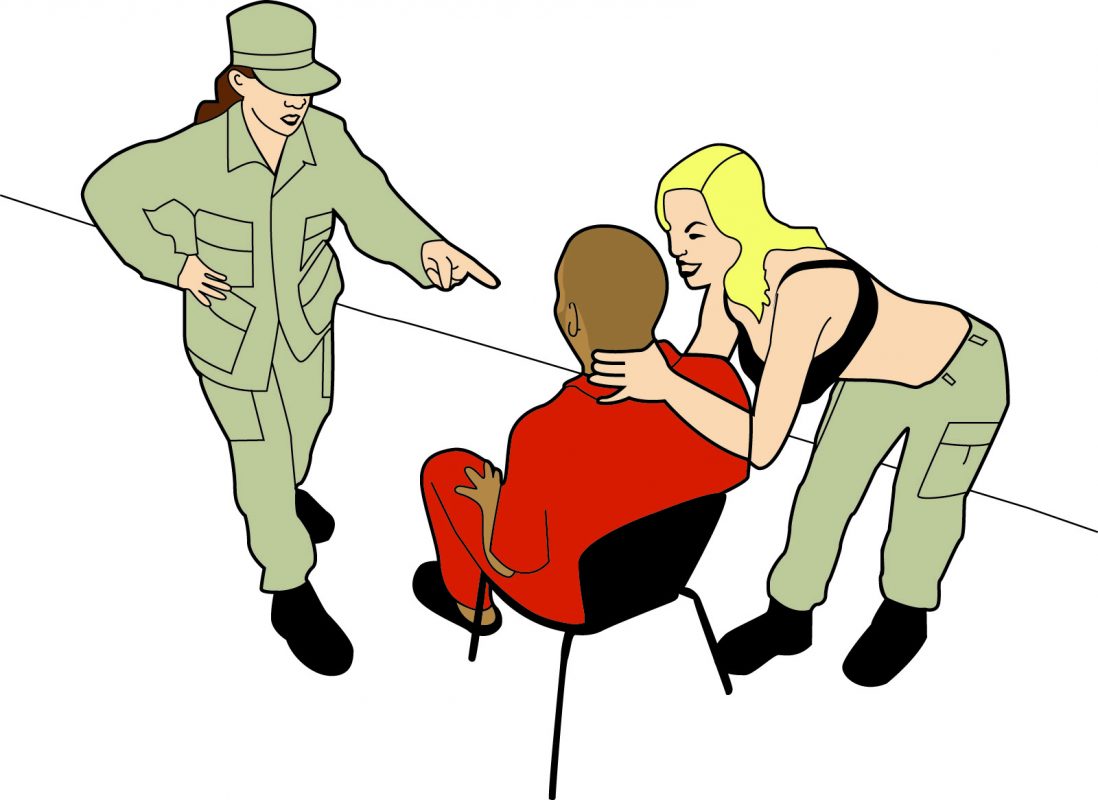

Elsewhere, Coco Fusco engenders other players. The interdisciplinary artist demands of us to consider how women, and photography, have come to be used as agents of torture particularly during interrogations of Muslim prisoners; with the Pentagon publicly confirming that sexual tactics are used on detainees. To discomforting effect, Fusco brings these notions to the infamous snapshots of naked detainees at Abu Ghraib, deploying the technical drawings of her alarmingly burlesque, A Field Guide for Female Interrogators.

Stefaan Decostere is not interviewed but instead contributes an essay in which Paul Virilio and other theorists are given credit for a somewhat confused concept. Responding to Sontag’s unstoppable images of war as hell, and invoking Elem Klimov’s 1985 film Come and See, he proposes ‘impactology’ as a science of the techniques of impact, the product his surround display of combat video, Warum 2.0. Theoretical ballast makes this the least satisfying of the contributions, and one is relieved when Decostere candidly reveals himself as both experimenter and specimen; “I see myself sneering at my own grotesqueness.”

Earlier this year Paul Hansen’s 20 November 2012 photograph for Dagens Nyheter won 2013 World Press Photo of the Year. His confronting pietà-esque depiction of lamenting uncles bearing corpses of two and three-year-old children killed in an Israeli missile strike attracted accusations from Neal Krawetz on the grounds that it was a Photoshopped montage. Multiplying its politics of Zionist/Hamas tensions, the notion was taken up by the neoconservative Front Page Magazine to declare Hansen’s image a pro-Hamas propaganda photo and a fraud. In fact, Hansen did no more than heighten his picture’s dynamic range, consistent with many World Press Photo entries where the documentary is given the aura of art. In such case, Stallabrass, his co-authors and interviewees, engaging comprehensively in the festival back in 2008 with conflict in images, and now re-evaluating and refining their analysis in this 2013 book, empower the reader to conjecture, providing a place to stand in the unending vortex of war and its representation. ♦

All images courtesy of Photoworks. Image 2 & 3 © Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales / Image 4 © Benjamin Lowry / Image 6 © Magnum Photos / Image 7 © Simon Norfolk / Image 8 © Geert van Kesteren / Image 9 © Coco Fusco / Image 10 © Bilal Hussein / Image 11 © Ghaith Abdul-Ahad & Getty Images / Image 13 © Geert van Kesteren / Image 14 © Ashley Gilbertson.

—

James McArdle is an artist and academic at Deakin University, Australia.