Les Rencontres d’Arles 2022

Top three festival highlights

Selected by Tim Clark

1000 Words Editor in Chief, Tim Clark, reports back from the opening of Les Rencontres d’Arles 2022, the 53rd edition of the bright, bushy-tailed festival set across the evocative Roman town in the south of France. Among the many exhibitions to salute are Norwegian-Nigerian artist Frida Orapabo’s How Fast Shall We Sing at Mécanique Générale in the dazzling new Parc des Ateliers at LUMA Arles, Rahim Fortune’s I can’t stand to see you cry as part of the Louis Roederer Discovery Award curated by Taous R. Dahmani and Sathish Kumar’s Town Boy, resulting from the first Serendipity Arles Grant in 2020. However, three particularly ambitious thematic exhibitions stand out for their complex visual dialogues and multiple vantage points onto the world and world of images.

1. But Still, It Turns

Musée départemental Arles antique

The wall text that introduces But Still, It Turns, the exhibition Paul Graham has curated at Musée départemental Arles antique – which, among many notable bodies of work, features Emanuele Brutti and Piergiorgio Casotti’s Index-G, Vanessa Winship’s she dances on Jackson and Curran Hatleberg’s Lost Coast – states, brazenly: ‘there is no didactic story here, no theme or artifice. None is asked, none is given.’ Isn’t no story, like when artists claim their work as ‘apolitical’, a story in itself? In this case, the ‘story’ – or rather, quasi-framework or exhibitionary complex – is that of a statement of positions on a mode of photography identified as so-called ‘post-documentary’. Its meta-narrative draws from a shared approach, or attitude, propagated by this judiciously selected group of photographers who, in one way or another, turn their lens on intimacies and small episodes of contemporary social realities in the US. Specifically, working in the observational mode, they opt to summon quiet or unremarkable moments as a means of possessing the weight of the world: a town and its inhabitants gripped by industrial decline, sounds and situations at the fault lines of race, environment and economy and so on. Yet there are no easy narratives – all is posed as fleeting and messy but also empathetic and genuine; what Graham refers to as ‘a consciousness of life, and its song’.

Originally staged at ICP, New York, But Still, It Turns in the context of Les Rencontres d’Arles is ultimately a hymn to traditional yet enduring forms of photography, its serious artistic application allowing ‘a kind of pathway through the cacophony – a way to see and embrace the storm.’ Graham writes: ‘It could guide you through the randomness and grant the simple mercy of recognising life in all its prismatic wonder’. That such complex dialogues emerge across these meaningful articulations from life, demonstrates the artists’ deep levels of understanding of the bonds between looking and caring, perceiving and visualising. And, unsurprisingly, there are echoes of Graham’s own work at every turn, redolent of a mountain towering over a landscape, whose image can only be glimpsed through its reflection in a lake below.

2. Songs of the Sky. Photography & The Cloud

Monoprix

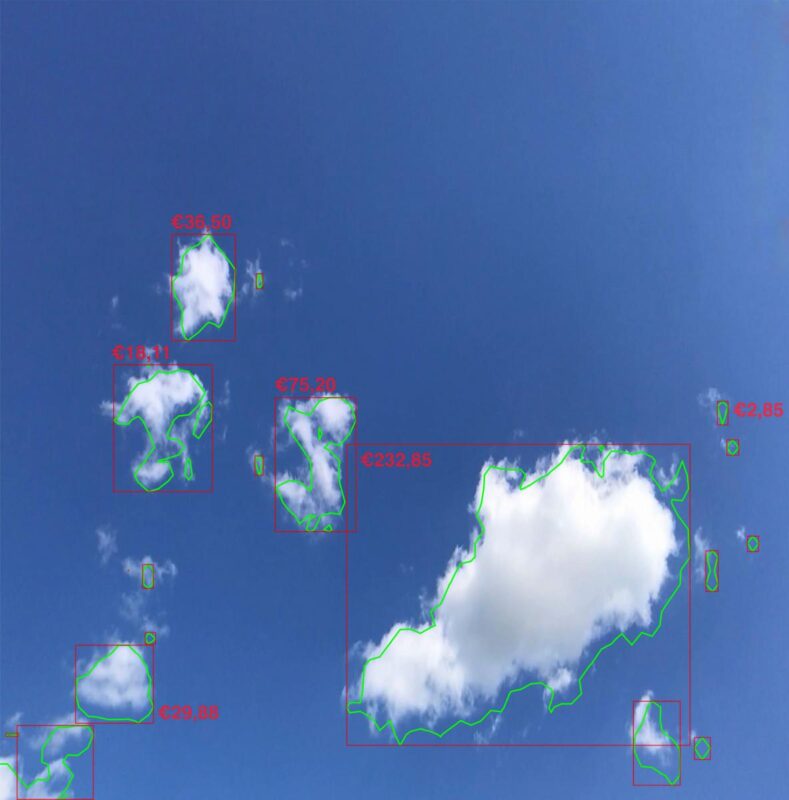

More curatorial (in the sense of thematising a group exhibition around a singular subject) is Songs of the Sky. Photography & The Cloud at Monoprix, the vast and industrial first-floor area above the French supermarket of the same name. As its title suggests, the show takes the motif of the cloud in photography as a starting point as well as the metaphor of ‘the cloud’ as a technological network that enables remote data storage and computing power commonly associated with the Internet. Of course, the empirical mass of photographs, i.e. those that exist on our smartphones and laptops – baby and cat photographs, holiday snaps, selfies, sunsets and pictures of food – or, by a similar token, those which have been generated by surveillance cameras and satellites, exist ‘up there’ in the cloud, finding in cables, screens and hard drives material form as part of the techno-capitalist system. Artists, on the other hand, have attempted to subvert and critique its principles, infrastructure and structures, ergo this exhibition.

Upon entering, one’s eyes don’t know where exactly to look; there are multiple sightlines onto numerous works from different artists but that’s certainly not a bad thing. As such, striking juxtapositions between historical material from the 19th century, such as Charles Nègre or Louis Vignes’ photographs, and contemporary works by Lisa Oppenheim, Trevor Paglen, Andy Sewell and Simon Roberts come to bear. What emerges is a tension between the sky as something sublime, as something which, for centuries, represented a way of ‘divining the future’ as James Bridle has put it, versus the far-from-romantic means we conceive of it today: a digital phenomenon that transfers and commodifies our data, with dramatic consequences for climate emergency and geo-politics. ‘Will the immense carbon footprint of the technical cloud accelerate global warming to such an extent that in the future it will be rare to see many faced cloud creatures floating by in the sky?’, is just one of the powerful research questions driving the exhibition. Organised with skill and clear focus, Songs of the Sky. Photography & The Cloud has been curated by Kathrin Schönegg of C/O Berlin, who was also the recipient of the 2019 Rencontres d’Arles Curatorial Research Fellowship.

3. Ritual Inhabitual, Geometric Forests: Struggles on Mapuche Land

Chapelle Saint-martin Du Méjan

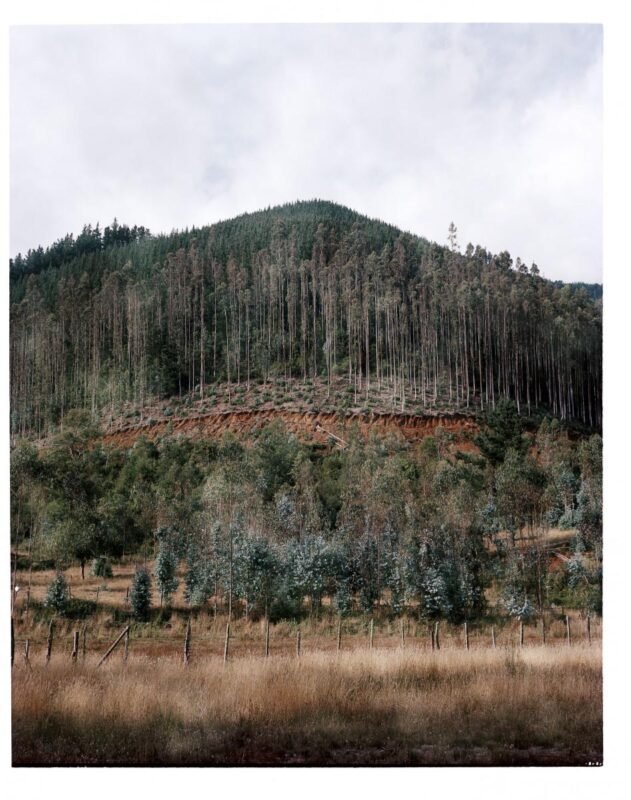

Native to the temperate rainforests in southern Chile are medicinal plants and a rich biodiversity that have bore witness to endless cycles of construction and destruction. Monocultures of pine and eucalyptus have now come to dominate in service to the hugely lucrative paper pulp industry in the region, Chile being the world’s fourth largest producer from its 2.87 million hectares of plantations after all. The Mapuche (“people of the earth”), meanwhile, have lived on this land long before the country was founded and now find themselves at the heart of an ongoing battle: their spiritual relationship with the environment is at odds with an aggressive, global economy based on the exploitation of natural resources, leading to violence between nationalist organisations, industrialists’ private militia and the army’s specialist anti-terror squad. In response to this conflict, Chilean collective Ritual Inhabitual, created by Florencia Grisanti and Tito Gonzalez García, embarked on a five year photographic and ethnobotanical investigation that encompasses delectable Wet Collodian plates as well as large and medium format colour photographs of members of the Mapuche community, plants, trees and cloning laboratories of a forestry company. That this project encompasses a broad range of cohorts is one of its strongest features, for it offers a multi-vantage point perspective onto the subject at hand. Deftly translated by the exhibition’s curator, Sergio Valenzuela-Escobedo, whose careful choreography of the space highlights these competing factions, Geometric Forests: Struggles on Mapuche Land mediates the political desire to open up a debate on the nature of consumption at large.

While aesthetics may write the script in other environmentally-concerned exhibitions, here a form of infrastructural activism that reflects on the actual conditions and implications of its own making is evident. The exhibition is therefore highly commendable for harnessing the possibility of thinking and talking otherwise about making art in a less extractive fashion, allied with the admission that an entirely eco-friendly exhibition of images is an impossibility. One obvious example of mitigating impact has been to reuse existing frames from previous exhibitions. Similarly, printing directly onto material surfaces bypassing the need for paper or gluing the print onto an archival cardboard as opposed to an aluminium substrate in the event the former cannot be achieved. Even some of the temporary exhibition structures are stripped back to show the bare bones utilisation of wood, itself dismountable and reusable. There is also a kind of in-built critique present in the blurb of the accompanying book, published with Actes Sud, with a particularly striking section revealing a consciousness and self-awareness. It reads: ‘3029 kilos of Munken Kristall paper and 814 kilos of Soposeet paper were used for the book, as well as 220 kilos of Munken Kristall paper for the cover. Based on 24 trees for one tonne of paper, 96 trees were needed to transform those 4,063 kg of paper into 2,200 copies of this book.’ Clearly, in Geometric Forests, its participants take up the responsibility to call for new socio-environmental-political forms of collaboration. Maybe, via the propositions and practices contained in this exhibition, there is a way forward together, a sustainable means of co-existence.♦

Les Rencontres d’Arles 2022 runs until 25 September 2022.

—

Tim Clark is Editor in Chief of 1000 Words and Artistic Director for Fotografia Europea in Reggio Emilia, Italy, together with Walter Guadagnini and Luce Lebart. He also currently serves as a curatorial advisor for Photo London Discovery and teaches at The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University.

Images:

1-Vanessa Winship, from the series She dances on Jackson, 2013, part of But Still, It Turns. Courtesy the artist and MACK.

2-Curran Hatleberg, from the series Lost Coast, 2016, part of But Still, It Turns. Courtesy the artist and MACK.

3-Kristine Potter, Drying Out, from the series Manifest, 2018, part of But Still, it Turns. Courtesy the artist and MACK.

4-Trevor Paglen, CLOUD #865 Hough Circle Transform, 2019, part of Songs of the Sky. Photography & The Cloud. Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery

5-Andy Sewell, Known and Strange Things Pass, 2020, part of Songs of the Sky. Photography & The Cloud. Courtesy the artist and Robert Morat Gallery.

6-Noa Jansma, Buycloud, 2020-21, part of Songs of the Sky. Photography & The Cloud. Courtesy the artist.

7-Ritual Inhabitual, Paul Filutraru, Rapper in the group Wechekeche ñi Trawün, Santiago de Chile, 2016, part of Geometric Forests: Struggles on Mapuche Land. Courtesy the artists.

8-Ritual Inhabitual, Biotechnology series, Chile, 2019, part of Geometric Forests: Struggles on Mapuche Land. Courtesy the artists.

9-Ritual Inhabitual, Geometric Forests series, Chile, 2018, part of Geometric Forests: Struggles on Mapuche Land. Courtesy the artists.