Writer Conversations #6

Daniel C. Blight

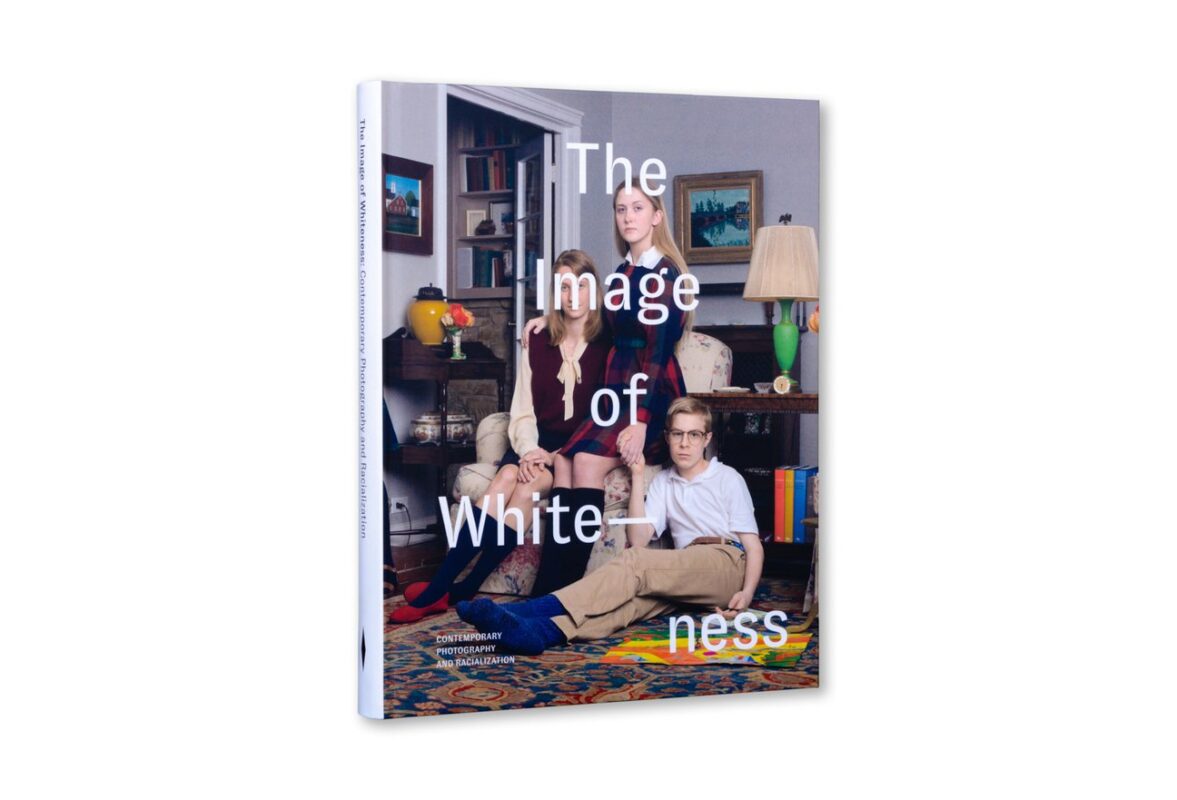

Daniel C. Blight is a writer based in London and Lecturer in Photography (Historical & Critical Studies) at University of Brighton. Recent work includes “Ways of Seeing Whiteness” in George Yancy: A Critical Introduction, eds. Kimberley Ducey, Joe R. Feagin and Clevis Headley (Rowman & Littlefield, 2021) and The Image of Whiteness: Contemporary Photography and Racialization (SPBH Editions/Art on the Underground 2019). He is currently working on a monograph, Photography’s White Racial Frame (Bloomsbury 2024), and slowly completing a PhD in the faculty of Social Science and Public Policy at King’s College London. In April 2022, he will be Visiting Scholar, Department of Art and Art History, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

At what point did you start to write about photographs?

I developed an interest in photography via post-rock and “electronica” album covers. The cityscape on the front of Fugazi’s End Hits (1998), the obliquely angled road sign on Hoover’s The Lurid Traversal of Route 7 (1994), or the pixelated “terrain” on the cover of Autechre’s Incunabula (1993) LP, which I took to be extra-terrestrial Swindon as I walked its streets, mashed at night, strangely under-stimulated. 20 years ago in that place, I made digital photographs and electronic music as part of a photography foundation course at Swindon College because, having quit my A Levels to become a pizza chef, it was the only route to university, an overdraft and a student loan.

My work then involved software editing digital photographs into CD artwork for the glitchy music I was making. I recorded the mechanical sounds of analogue camera shutters, cutting them up and sequencing them into drumbeats, and then manipulating tonally-inverted photographs of lightning to visually represent the glitches. It was as bad as it sounds. One of the compositions I completed then was titled Just take the fucking photo. This was the first time I wrote about photographs – or should that be “photography”? – eventually repeating the phrase into a microphone and layering the recorded voice track over camera shutter rhythms constructed in Fruity Loops, an audio sequencer of sorts.

My first experience of writing about photography is a species of repetitive song lyric: “Just take the fucking photo”, I wrote aggressively, over and over, on a piece of note paper in my teenage bedroom. In a sense, all my writing about photography since then has been born from the frustration captured in that phrase. Although I like to think I’m able to work with more “complex” forms of writing nowadays, there is a large part of me that appreciates teenage quotidian writing, an adolescent poetic writing, a writing apart from the perceived maturity of scholarly aptitude and normative citation practices.

On reflection, I feel there is something to learn from my frustration. What if my writing is frustration? What if I was supposed to be a writer not because I had anything interesting to say, but so that I could enjoy all the other things I do because my frustrations were absorbed by and confined to my writing? I count myself lucky that I have figured out how to confine frustration. I’ve sealed it into a sort of literary defeat.

What is your writing process?

‘Process’ sounds like such a clinical and serious word to describe how I write, although I like the sound of one of the word’s synonyms — ‘unfolding’. A procrastinatory unfolding. I enjoy reducing myself to a state of under-stimulation over a period of two or three days. Eventually, boredom compels me to write. At that point the smallest thing feels new, wakes me up and gets me excited again. Often cooking, or fixating on a particular image in a book.

I spend most of my time not writing. I find this a necessary part of the process leading up to the act itself (which is both a struggle and a performance to myself – can I do it? Should I do it? Will it work?). Things don’t unfold this way deliberately. Most of the time, I just can’t write. It seems too hard, too difficult. I think coming to terms with this is the most important part of my writing in a philosophical sense. I like the idea, more and more, of slow writing, and of selective writing.

The rest is practical: reading, mostly on a screen, apart from poetry which I tend to read on paper. Looking at pictures in printed books. Making mental notes. Forgetting things. Then eventually I write something when I feel I can. I collect quotations when I’m reading. When I’m writing essays, I often use these to structure text. I write before them, after them, in the middle of them to disrupt them, and to see what happens. I largely write in incoherent, broken fragments which I call paragraphs. I can’t always be clear because I don’t really know what I mean. I call this writerly honesty. I’m trying to describe a feeling using words that are always wrong.

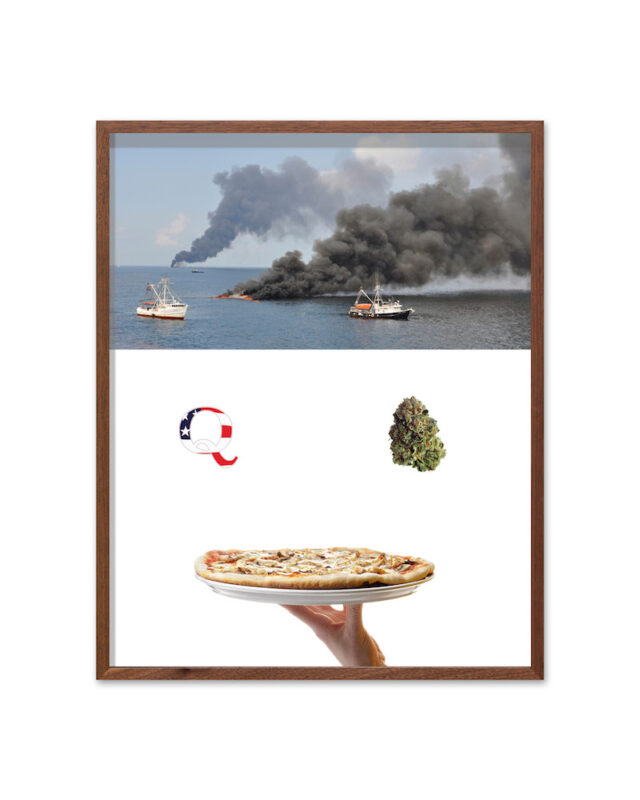

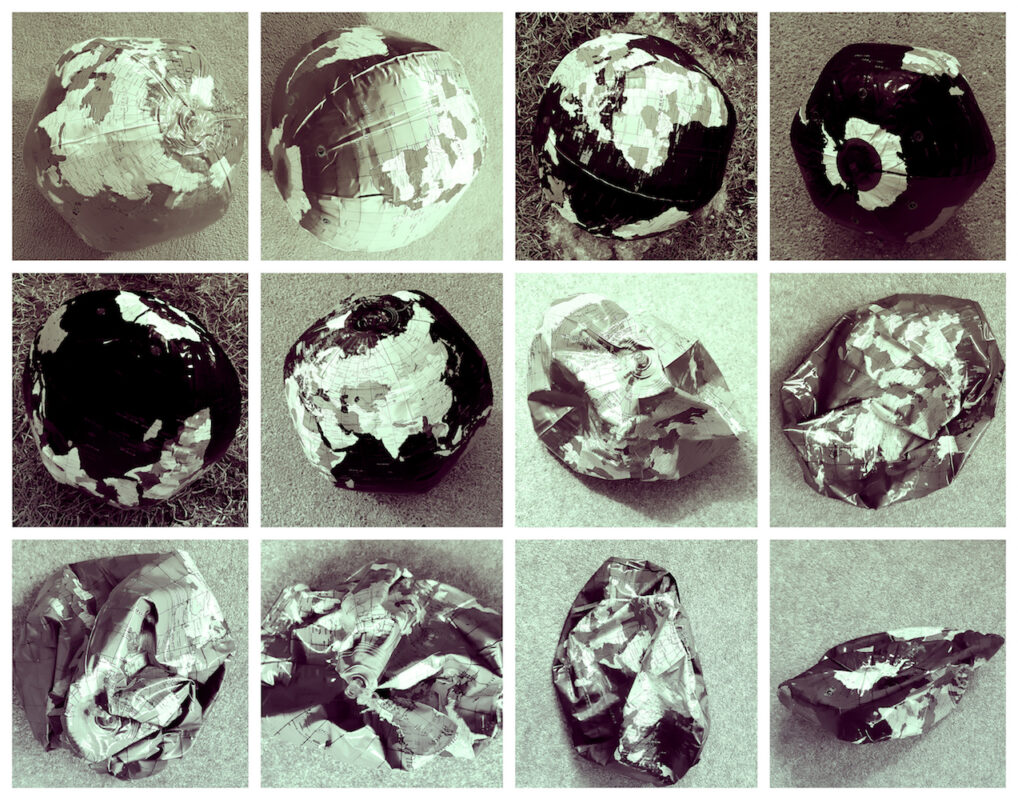

Since 2013, I’ve been making visual cues to aid my writing. I call these Image Reconstructions and they are collages comprised of visual symbols that summarise the subjects of texts I am working on. I collect images in folders as I research and read: the QAnon “logo”, a photograph of some weed, a Creative Commons image of oil burning on the surface of the sea, a .png of a pizza held up by a white hand. I then group them together into meaningful compositions (see the image nug, 2021). The rest is a weird form of visualisation in which images come to life through speculation, appropriation, trying things out to visually represent meaning. Sometimes I can’t finish the essay, or the poem, and it instead becomes an image reconstructed from the practice of writing. Sometimes I can’t finish the image. Most of the time nothing is finished, and nothing gets made, and that’s OK too.

It sounds a cliché – and I hate the empty verbosity of the conceptual framing – but I prefer to write with photographs rather than about or, in the oft-repeated phrase, on them. I produce an essay plan using images and quotations in close and strange juxtapositions. I look for resonances, contradictions, parallels. My habits have been reformed by The Virus and by family life, particularly children. I no longer feel a need to write all the time. Most of the time I just don’t want to. I’d rather read or listen. I write towards happiness and in the direction of freedom. I’m much more comfortable with that cliché.

Can you expand on what draws you to slow writing? Is there an act of refusal, a determination to take time, in this? You’ve begun to focus much more on longer form writing over the short form.

In a sense, this isn’t true because I write many more short poems than I do long essays. Perhaps a poem a month, and two or three essays a year? I politely decline most invitations to write short form for magazines and newspapers nowadays. There are other people much better placed to comment on new projects and exhibitions than I am. There are certain spaces I don’t wish to occupy any longer. I am also disillusioned with the way badly paid short form essay writing for magazines and newspapers forces me to focus on some specious idea of right now, responding to “current practice”. Slow writing is something that the world of photography magazines can’t contend with, but they need it badly. Slow writing is a needed practice in academia too, in which scholars are forced to produce at pace to satisfy the various “excellence frameworks” they are compelled to adhere to. How many journal articles do I need to get a promotion? Are we talking 10 mediocre articles, or one bad boy one? Who gets to decide whether I’m any good or not?

If “right now” is both a fashionable position culturally speaking, and a global catastrophe unfolding in strikingly visual terms (images of the sea on fire, shamanic QAnon fascists storming the Capitol, Boris Johnson talking shit on the BBC), I’m looking to respond more slowly certainly. Part of what capitalism’s recently rejuvenated intersection with fascism requires of us is that we keep up. Move fast and stay relevant! I’m not the first person to say we should refuse that. I want to go back to a time when I could walk the streets stoned at night slowly with nowhere to be. I want to make pizzas for minimum wage again. But this time they’re texts, and I get to bake them for longer than four minutes. Unfortunately weed makes me puke now, so I can’t smoke, and I earned more money working as a waiter at Pizza Express than I do as an academic.

Slow writing is a form of epistemic protest. It says to me: stop producing knowledge habitually until you understand your own epistemic standpoint. Or: work to produce a kind of counter-knowledge that supports other people. Slowing down is me trying to be less selfish. Perhaps the “knowledge” I possess is a form of what Charles W. Mills called ‘white ignorance’ before he recently passed. I have thought about this in more detail in a chapter for a new book on the philosopher George Yancy. In that essay, I consider his work, his excellence, and myself, as I am.

What are the questions or problems that motivate your writing?

I write to edge away from the disappointment of my social self. To be white, and to be a man, is in two interlinked ways to be a problem. Therefore, the superficial problem of my work is me, and by extension the fundamental problems are white supremacy and the elite white male dominance system. I write in the hope that I can become someone else, someone better. I am in my own way, tripping over my own feet. This is a process of discovery in which my social self is cracked open; breached to form a sort of aperture. I want to write despite myself. I have come to understand this more recently as a willingness on my part to become vulnerable, to fail publicly, to not care about the consequences of doing so. It’s only through a kind of risk that anything meaningful can come of my writing. The trouble is risk is predominantly about failure. My process is just that, then: attempt to escape myself; fail. A strangely productive failure.

Isn’t it true that writers can’t name themselves? My writing began with frustration, and its continuation now involves wondering whether what I write next will result in another “race traitor!” death threat via email. Yet, with this violence in mind, how can I not name myself? I am a white writer coming to terms with what it’s like to unravel in words. I think all white writers should try this. This is not a melancholy unfolding though, and it is not one that requires any emotional sympathy, nor undue attention. I am deeply happy. I am filled with love for other people’s writing, other people’s poetry, other people – for the first time in a long time.

What kind of reader are you?

I read long essays quickly and short poems slowly. Then I read the same essays slowly and have no time left to read poems. I read with admiration, curiosity, frustration. I read searching for something I never find.

What do you go looking for in your reading?

I look for a mix of deep exegesis and personal reflection. Often one leads to the other. It’s sort of like asking what I go looking for in food. How much time do I have? Am I in the mood to cook? Do I have a Tesco lasagne I can put in the microwave, squirt extra ketchup on top of, and dip chunks of garlic bread into? Or am I in a Michelin Star pub for my birthday rinsing it hard on my credit card? When I read, I gorge uncertainly, and its often done in such a way that makes me feel I’m avoiding rather than looking for things. I’m avoiding writers like me. I do think “What do I want to read?” before I read sometimes, but it’s not like I always have much choice when one article takes me via a hyperlink to another, over and over again. I’ve read so much, partially. I keep trying to read in print again, and then I start missing all the hyperlinks, the distractions on Wikipedia, the stopping and searching for things I don’t understand in journal articles on the University of Brighton’s online library.

I enjoy reading my student’s essays. They teach me how to read and they teach me how to write. It’s a wonderful thing, teaching. I used to conceptualise it as something I did to feed myself so I could concentrate on my writing, but now it’s a thing I do to actively learn. I read with pleasure in a community of student-scholars. This year, I will work with students to encounter racial whiteness in reading photographs. This is a process in which we “let go” of the white logic and white racist visual foundations that underpin the western colonial history of photography and instead turn our attention to forms of white uncertainty. Irrespective of our individual racial identifications, we all work together in a white university. In a white space. In white complicity pedagogy, this involves de-centring forms of “knowing” and instead centres notions of white humility (“I do not know”/”I am not sure”) and white listening – learning to listen while giving up on needing to feel like a “good” white scholar. I take my lead here from educators such as Barbara Applebaum, Stephen Brookefield and Zeus Leonardo.

Reading should always be paired with writing. This doesn’t necessarily mean essay writing, but perhaps a simpler form of writing notes, questions or incomplete fragments. I encourage students to read in such a way that excites them to produce fragments of text, as roughly as they like. We then work through those texts together and make sense of them in critical relation to scholarly conventions. What results is a form of photo-textual essay practice; a manner of writing with photographs in order to produce literary essays that respond both to a history of the essay form in photographic cultures, and importantly, embodied, reflexive and phenomenological approaches to images derived from methods in visual sociology. It sounds technical, but it’s exciting, in practice, in the classroom.

How significant are theories and histories of photography now that curation is so prominent?

The sort of canonical history of photography taught in British Higher Education is undergirded by the white logic of European settler colonialism. This isn’t discussed nearly enough, and it has a huge impact on what is often falsely named the history of photography and how we theorise its structures and meanings (in this way history and theory go hand in hand). We desperately need new historical and theoretical frameworks because the European invention of photography from the 1830s – which is not the first invention of photography, but rather the most convenient white inauguration – is founded upon the same intellectual traditions that justify the genocide of Indigenous, Black and Brown people the world over. After Gerald Horne, let’s call this tradition the apocalypse of settler colonialism, and, after Charles W. Mills, let’s call it the white ignorance of epistemological individualism in the historical project of racial liberalism. In short, white supremacy continues to govern the world at large, and all cultural phenomena including photography falls within its scope and power.

More precisely, the European invention of photography, which is to say the “fixing” of images by such figures as William Henry Fox Talbot in the middle of the 19th century (some 200 years after the invention of racial whiteness), is a visual project that inherits the social dynamics of what Joe R. Feagin calls the white racial frame and extends this into particular types of “image-schema”. This image-schema, which I am theorising in a new book, Photography’s White Racial Frame, can be described in several ways. It is first and foremost a mental frame, or what has been described differently as the colonial gaze by Frantz Fanon and Edward Said. More precisely, this mental frame is named white scopophilia by George Yancy, and a regime of seeing by Kalpana Seshadri-Crooks. These concepts share a common truth: that with the invention of racial whiteness came what might be called a psychology of colonial picturing. This is a form of white imaginary, which is of course etymologically to say white imagery. We white people look at the world through what Stuart Hall called a white eye, and we do so full of an often-unconscious desire for power, wealth and knowledge. Photography is the great inheritor of this perceptual frame, this image-schema and its false narrative of white violence then and white innocence now. Thus, I theorise the European history of photography as a white racist visual dynamic full of emancipatory potential in the hands of those artists that choose to work against it. Like racial whiteness, photography can be abolished.

Understanding the significant violence of this visual framework should result in nothing less than seeing the world in an entirely new way, and as I have contended, seeing one’s white self in an entirely new way. If curation is the care and organisation of cultural phenomena, then in a white supremacist world it either stands within or without the white racial frame. The practice of curating is an historical and theoretical positioning which takes place in relation to the history of the western museum defined as (what Dan Hicks calls) ‘white infrastructure’. So, the question becomes, why is curating now so prominent? And for me, the answer has to do with the false choices racial whiteness continues to offer curators (remember, everyone is a curator, but it is most often white people that declare themselves so or who are awarded the title institutionally). To curate is first to possess knowledge, and then to make choices based on that knowledge resulting in some objects getting attention and others not. Possession is privilege. Knowledge is racialised, gendered, made bodily. Which curatorial bodies are most prominent? Ones like mine. Like racial whiteness, white curators can be abolished too.

Your book The Image of Whiteness, examining photography’s construction and perpetuation of racialised hierarchy, felt like it could have been an exhibition, but existed in book form. Was that a choice you made, or does it reveal something about the spaces of writing and display?

The Image of Whiteness is visually intrusive and conceptually shocking for lots of white people – certainly if encountered as an exhibition, in a public museum space (white infrastructure). I owe this to the artists featured. They have done the work and I have brought it together. I think it would be interesting if there was an accompanying events programme in which people could thrash out some of the ideas in the project. George Yancy might deliver the keynote on the question of symbolic white death – he’s an excellent public speaker – and I could be available as white visitors feel more and more uncomfortable, just like I do every day as I try to learn about my white self. I would be there to care for them (the curator’s role), not to make them feel good but to make them understand that it’s OK to feel uncomfortable and confused by something we are only just coming to understand: that being white is to embody a violent lie; that the exhibition is teaching us that we have been lied to, and that we are upholding that lie and that what we need do is look, and then see differently, and listen attentively. That’s what I hope The Image of Whiteness is about: rendering white people uncomfortable so that we can be challenged and then learn. We white people need to learn to feel – to racially empathise – and then to self-disclose. I’m not interested in books or exhibitions that revive whiteness or make it “good”. That is an impossibility. A paradoxical space of both white projection and display.

White self-disclosure starts from the position that there is ‘no contradiction in whites working as anti-racists and their being racist,’ as Stephen Brookefield writes. So, I start from that position in my own work, and when I encounter white denialists – those individuals socialised white that have unfortunately still not realised their racial whiteness has very little to do with their skin colour – I seek to help them through a form of creative care. Imagine if that could be communicated to an exhibition audience? This is not to say white viewers should be told they are racist upon entry to the museum, but that they will surely come to realise to be white is to be racist by the time they leave. The exhibition becomes a form of white abolitionist narrative disclosure in which white people are prompted to learn through a process of looking and seeing differently.

Whatever The Image of Whiteness is, I hope it is not a mere anti-racist declaration. I am interested in avoiding spaces of epistemic comfort for myself and other white people. I want to create thankful spaces in which abolitionist practice is uncomfortable and ongoing. An anti-white social ontology requires a complex theory of practice that understands the space between white agency and white social structure as a fissure in which a series of epistemic possibilities might be revealed. My writing, and any exhibition making that follows it, is about revealing in this way. I reject error avoidance as I will make errors as I go. In a sense to be white is to be a human error, so what would it be like to accept that glitch in the social matrix from the get-go? What if instead of conceptualising my work as “good” I call it an error – which is different from a mistake – and brings me all the way back to where I started: frustration, erratum, not writing until I have something to say, or rather, something to do.

What qualities do you admire in other writers?

I admire anyone who has the courage to write against themselves.

What texts have influenced you the most?

Here’s what is influencing me this week: Simple Men (2019) by Rachael Allen; To Revive a Person is No Slight Thing (2016) by Diane Williams; White Self-Criticality Beyond Anti-Racism: How Does it Feel to Be a White Problem? (2014), edited by George Yancy; Weird Fucks (1980) by Lynne Tillman; Black Bodies, White Gold (2021) by Anna Arabindan-Kesson.

What is the place of criticality in photography writing now?

Criticism gets me in trouble. Always with white people in positions of power, which is reason enough to keep getting in trouble.♦

Further interviews in the Writer Conversations series can be read here.

Click here to order your copy of the book

—

Writer Conversations is edited by Lucy Soutter (University of Westminster) and Duncan Wooldridge (Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London), upon the invitation of Tim Clark (1000 Words and The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University).

Images:

1-Portrait of Daniel C. Blight. © Idris Khan OBE

2-Book cover of Daniel C. Blight, The Image of Whiteness (SPBH Editions and Art on the Underground, 2019)

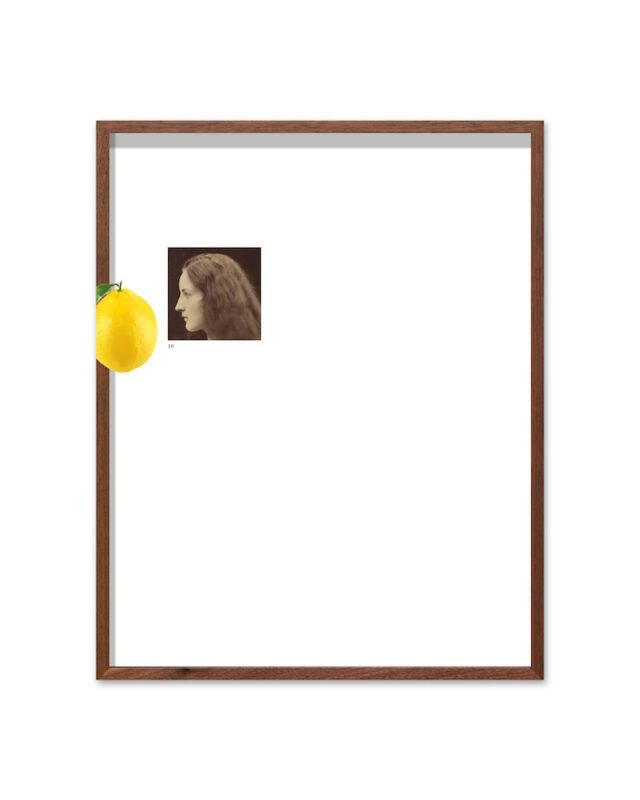

3-Daniel C. Blight, 010 (After Julia Margaret Cameron, The Echo, 1868 (2021), from A selection of white people’s expressions from the great period of realism organised into a grid and positioned in such a way that they can smell a lemon. Photographs on archival paper, walnut frame © Daniel C. Blight

4-Daniel C. Blight, nug (2021), from Image Reconstructions. Photographs on archival paper, walnut frame © Daniel C. Blight

5-LP cover of Autechre, Incunabula (1993) © Warp Records