Mariela Sancari

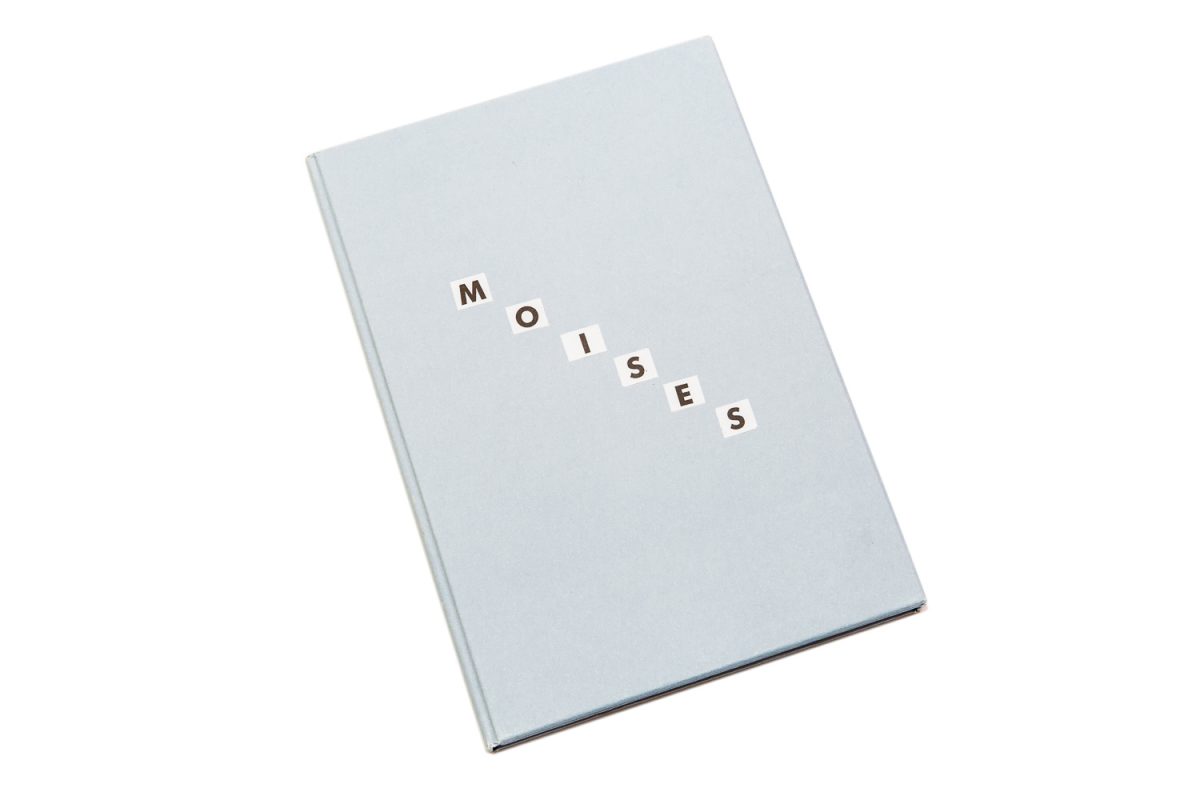

Moises

La Fabrica

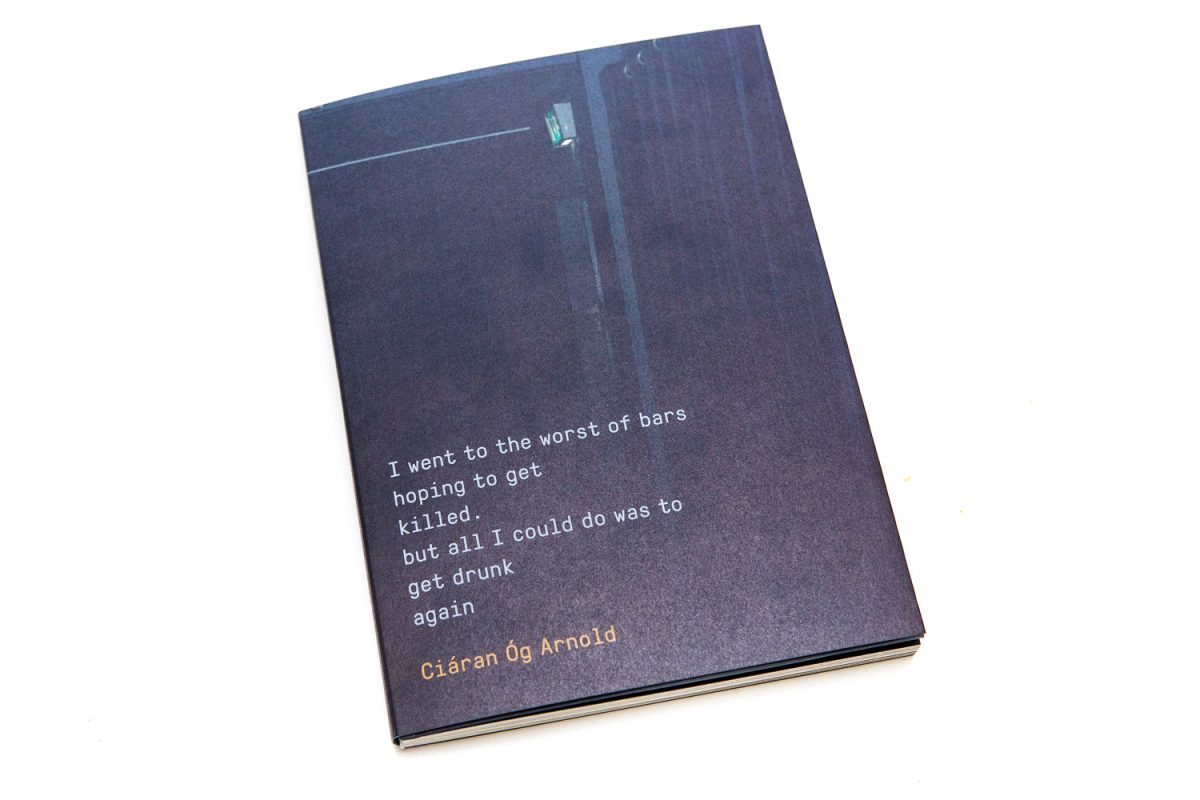

There is no shortage of photobooks dealing with the loss or absence of a loved one but Mariela Sancari’s Moises must be one of the more touching testimonies to the void a person can leave in the lives of others. Growing up in Buenos Aires, at the age of fourteen Sancari’s father, Moises killed himself. Years later the photographer placed adverts in various newspapers from her home city seeking men of the age her father would have been had he still been alive.

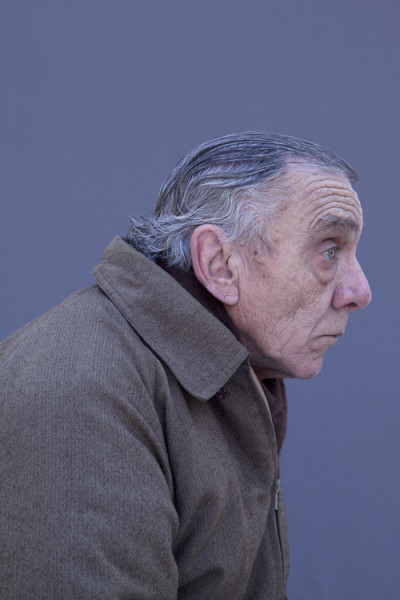

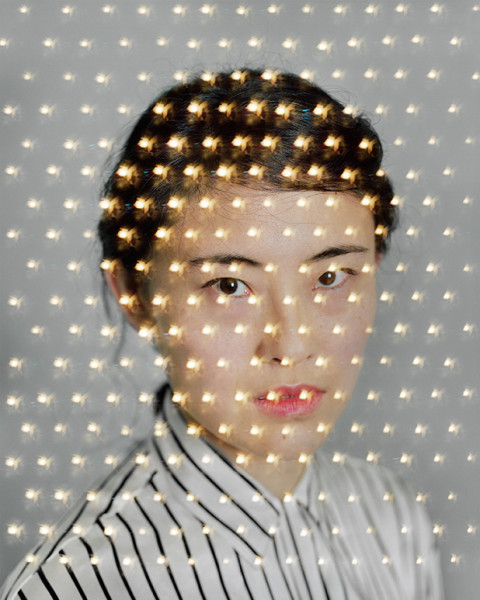

Moises consists of portraits of those men that responded, pictured from a variety of angles, against neutral backdrops and often wearing the same knitted sweater that had once belonged to her father. Such a simple concept belies a book of surprising depth. Opening the double cover the viewer is confronted with two interlocking sets of pages, which interlace with one another as each page is ‘turned’. As a metaphor for the fragmentary and unpredictable nature of memory it’s a perfect device.

Despite their simplicity and typological feel, the photographs also manage to prove very moving. Partly, it’s because they work as powerful reminder of the way that many of us use photography to search for, or create, the things we lack in life. It’s also touching in that the men themselves seem so vulnerable and out on a limb. Greying hair and the spots and marks of age are all on show. These photographs won’t just be resonant for anyone who has lost someone, but for anyone who watched a parent grow old, or for anyone who has thought for a moment that they recognised their mother or a father in the face or gait of an elderly stranger on the street.

Unlike many photobooks that drag out their point, Moises ends before you feel that what little narrative there is has resolved itself. There is no happy ending or comfortable resolution, nor any afterword to offer a viewer closure. In a lesser book this would awkward and strange, but given the tragic history underneath it all this lack of a clear ending is fittingly poignant.

—Lewis Bush

All images courtesy of the artist. © Mariela Sancari