Alexandra Lethbridge

Other Ways of Knowing

Essay by Lisa Stein

In his introduction to Downcast Eyes: The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-Century French Thought, Martin Jay observes that ‘we are often fooled by visual experience that turns out to be illusory, an inclination generated perhaps by our overwhelming, habitual belief in its apparent reliability’. Distinguishing between ‘the “natural” and the “cultural” component in what we call vision’, Jay maintains that it is not only our scientific understanding of the function of the eye – its superior capacity to process external data, and the rate at which this information is transferred to the brain via the optic nerve – that led to the privileging of vision over the other four senses. His opening paragraph testifies to what Jay refers to as the ‘ocular permeation of language’; containing numerous visual metaphors, it reveals that our ability to interpret, negotiate and make meaning from what we see is likely to have played an equally important role in locating vision at the top of the sensual hierarchy. However, Jay proceeds to demonstrate that the ‘permeability of the boundary between the “natural” and the “cultural”’ – take the word “image”, which can ‘signify graphic, optical, perceptual, mental, or verbal phenomena’ – would ultimately lead to the very premises of “ocularcentrism” being called into question. Still, it is not only the ambiguities inherent in any one language, but the ‘wealth of visually imbued cultural and social practices, which vary from culture to culture’ that Jay believes further complicate the idea that ‘knowledge is the state of having seen’.

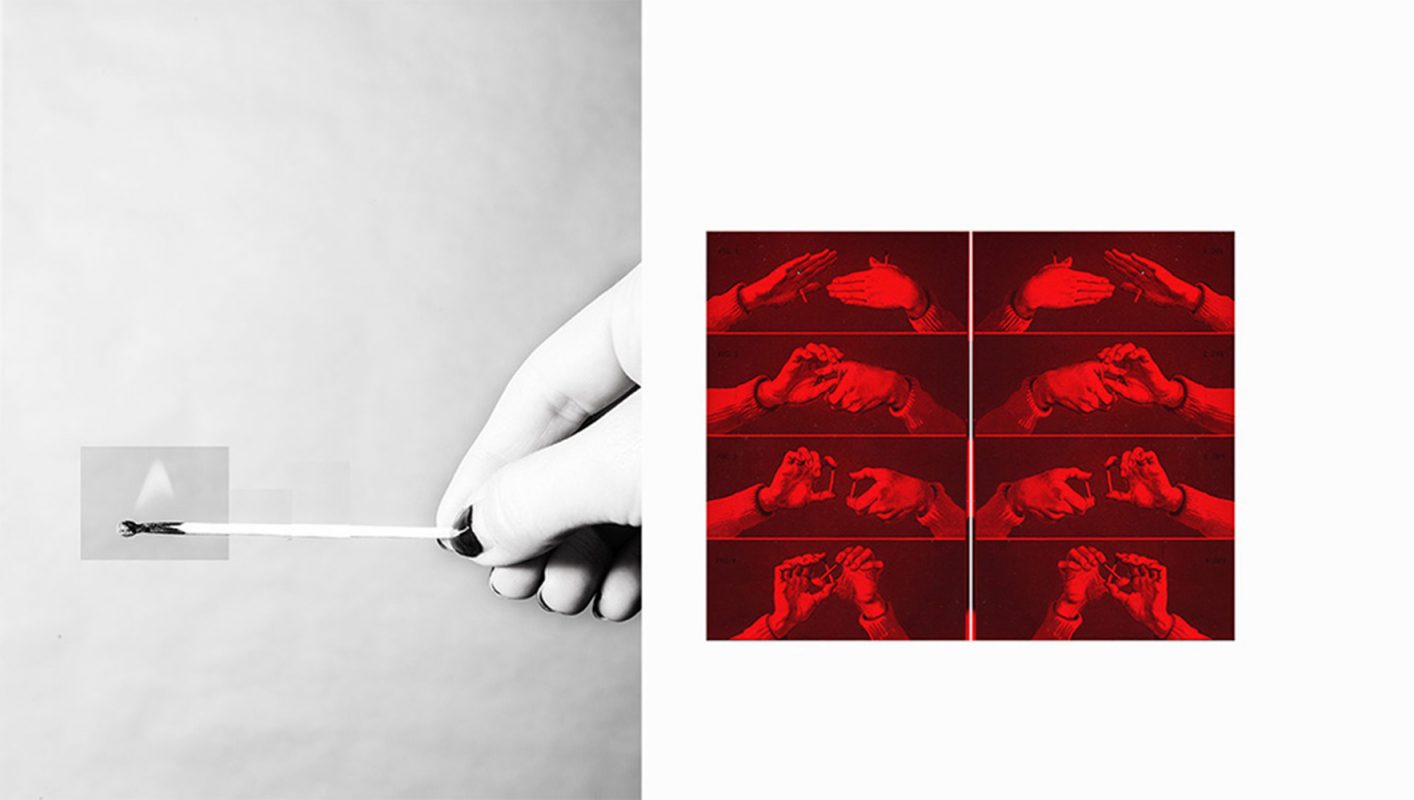

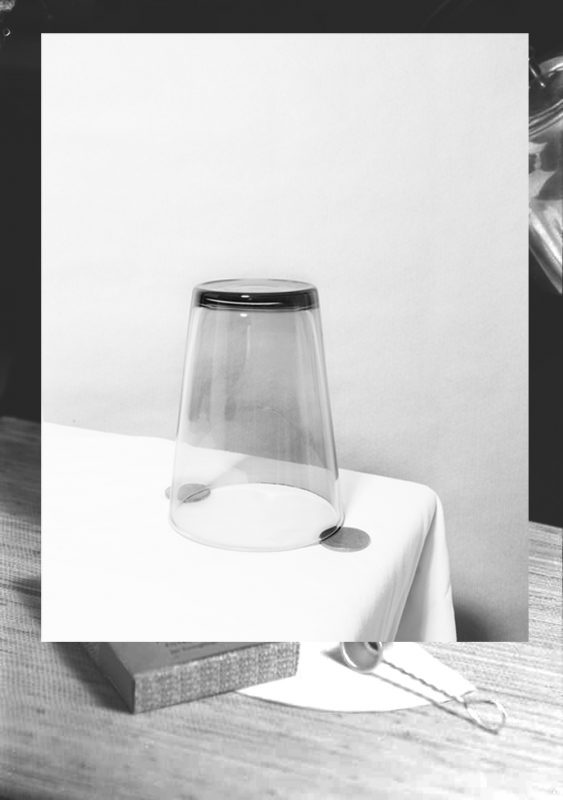

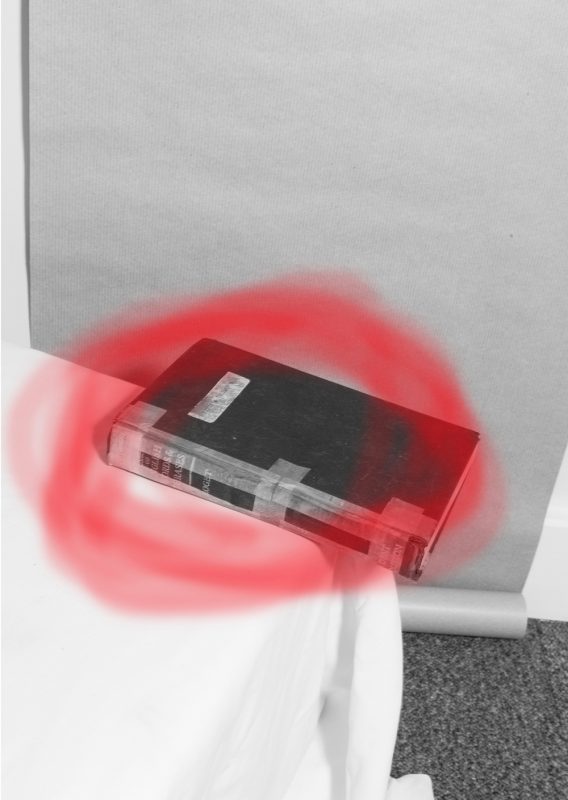

Other Ways of Knowing, Alexandra Lethbridge’s ‘exploration into the illusion of magic and misdirection in comparison to ideas of hoax, deceit and trickery’, draws on the discrepancy between visual and cognitive perception, and examines the role of photography within that binary. The type of magic represented in the series, which combines found photographs, archival imagery and the artist’s own, ‘constructed’ photographs, is often referred to as “stage” or “street” magic to distinguish it from the paranormal or ritual kind, which aims to control supernatural forces. Using items such as playing cards, coins, cups or balls, the stage or street magician entertains an audience by performing tricks, effects or illusions; everyday objects are made to disappear, to defy gravity or to pass through other, solid objects. The magic performance disrupts and alters the relationship between our sensory and cognitive processes; by exploiting our belief in the infallibility of vision, the magician is able to perform seemingly supernatural feats that challenge the way we think. For instance, while we cannot actually “see” a coin passing through the wall of a glass because we know it is an illusion, we think we see it happening because we expect to, or indeed, because we want to. In that moment, our desire to believe that what we are seeing is possible leads to a reversal of visual literacy; we are no longer decoding, but encoding. In other words, our pre-existing knowledge influences what we see and how we choose to interpret this information or, in the case of the magic trick, to disregard it. For a brief moment, we do not want to know.

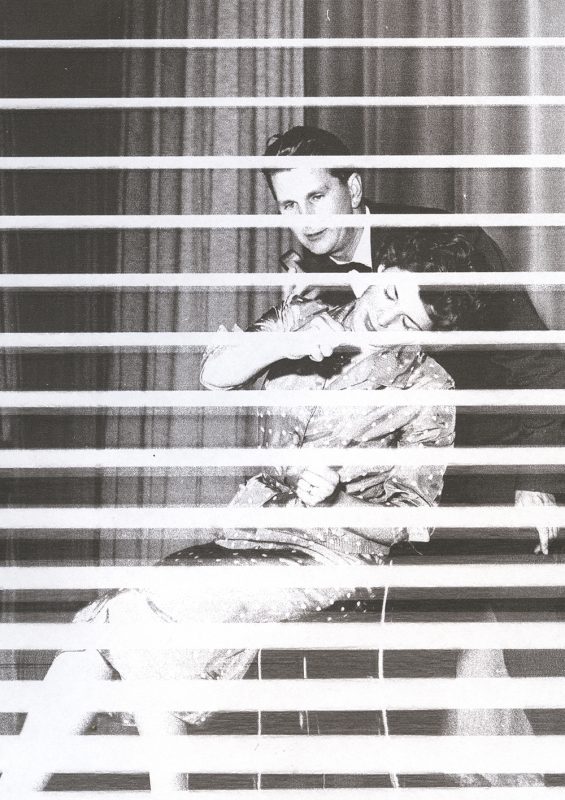

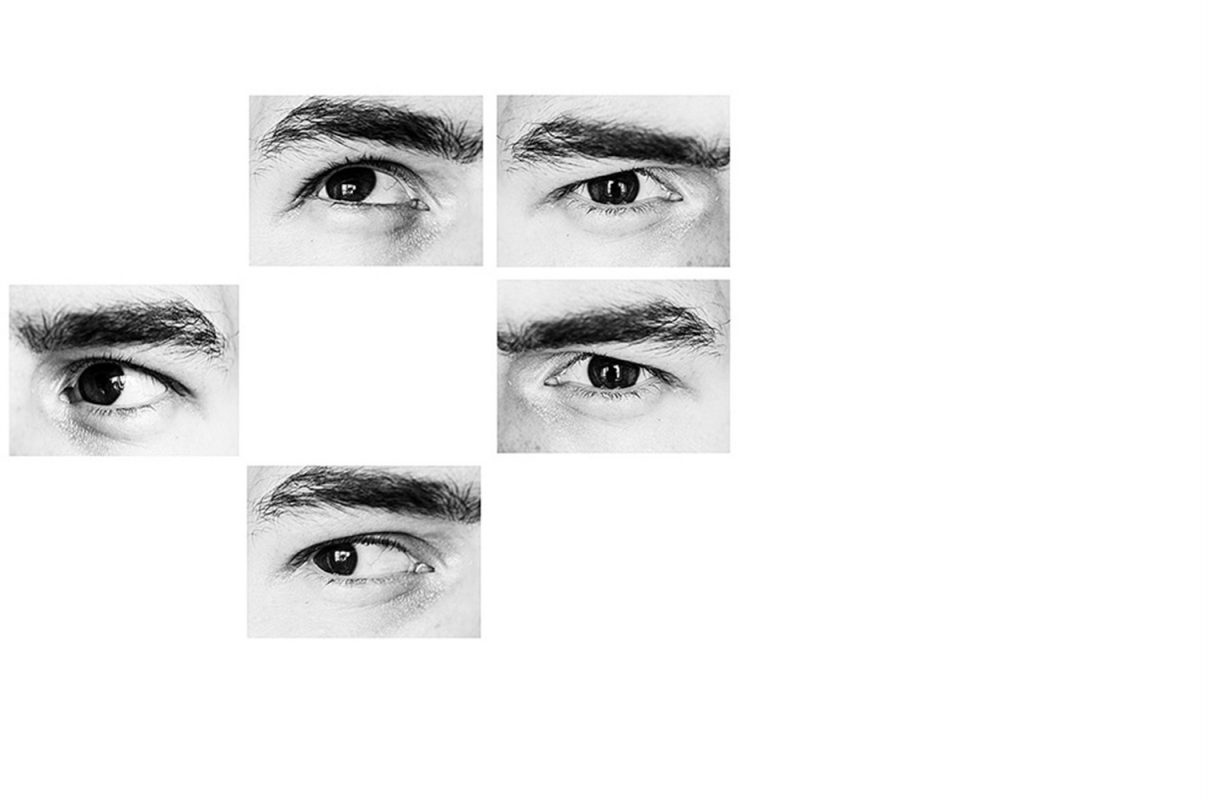

Like a magic performance, the photographs in Other Ways of Knowing ‘are designed to promote uncertainty in the viewer’s understanding in what they see’. Indeed, Lethbridge’s still-lifes, abstract compositions, portraits and sequenced photographs do not allow for a straightforward “reading”. By layering images, using multiple exposures and strategically placing graphic elements throughout her photographs, the artist controls our gaze; like the magician, Lethbridge instructs us where to look, what to see. Black arrows and bright colours direct our eyes and initially, consumed with wonder, we give into the performance. However, wonder at even the most thoroughly crafted magic trick soon gives way to scepticism, and as our eyes begin to move through her photographs more naturally we grow suspicious of Lethbridge’s visual interventions. Particularly upon revisiting a sequence of images depicting hands performing a magic trick, or a set of photographs revealing the construction of an impossible object, we ask ourselves whether these visual “clues” and “solutions” are being offered up too readily. Even Lethbridge’s censorship of elements one might consider fundamental to reading a photograph, like a face or a hand, seem like a deliberate distraction. However, if this is misdirection, which ‘deceives not only the eye of the spectator, but his mind as well’, it begs the question what exactly Lethbridge is trying to distract us from. What are we missing? Considering that the success of a magic trick lies in the extent to which it can challenge our cognitive processes, perhaps the question is not what we know about these photographs, but what we do not know.

Looking at the images in Other Ways of Knowing we might ask ourselves whether what is “true” about a magic trick resides in the performance of the magician or in the mind of the audience. We might ask ourselves where the “magic” happens. One could argue that what makes a trick “real”, what defines it as magic, is our wonder at what we (think we) can see, not what we know about how it is executed. By focusing on ‘aesthetic judgment rather than abstract reasoning’, Lethbridge forces us to reconsider our understanding of “truth” in relation to the photograph, which registers numerous ways of “seeing”. Indeed, while Jay’s notion that vision is informed by culture might not mean that a photograph cannot depict reality, it suggests that what is considered “real” might differ in the mind of the photographer versus that of (a) viewer(s), say. This leaves the question of what we can gain from what we do not know about a photograph. In Photography is Magic, a survey of artists that engage ‘with experimental approaches to photographic ideas’, Charlotte Cotton observes that a magic trick, like all performative art forms played well, creates the conditions for us to explore imaginative possibilities’. In other words it is the experience of not knowing that forces us to reflect upon ourselves and how we “see” the world. If a photograph that we do not understand is more likely to make us reconsider our (visual) culture, there is more truth to the manipulated images in Other Ways of Knowing than the most visually accurate of photographs. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Alexandra Lethbridge

—

Lisa Stein is a London-based writer and researcher specialising in photography. Managing Editor of the photo-literary platform Photocaptionist and Editorial Assistant at The Burlington Magazine, her writing has also appeared in The Philosophy of Photography.