Rahim Fortune

Hardtack

Book review by Taous R. Dahmani

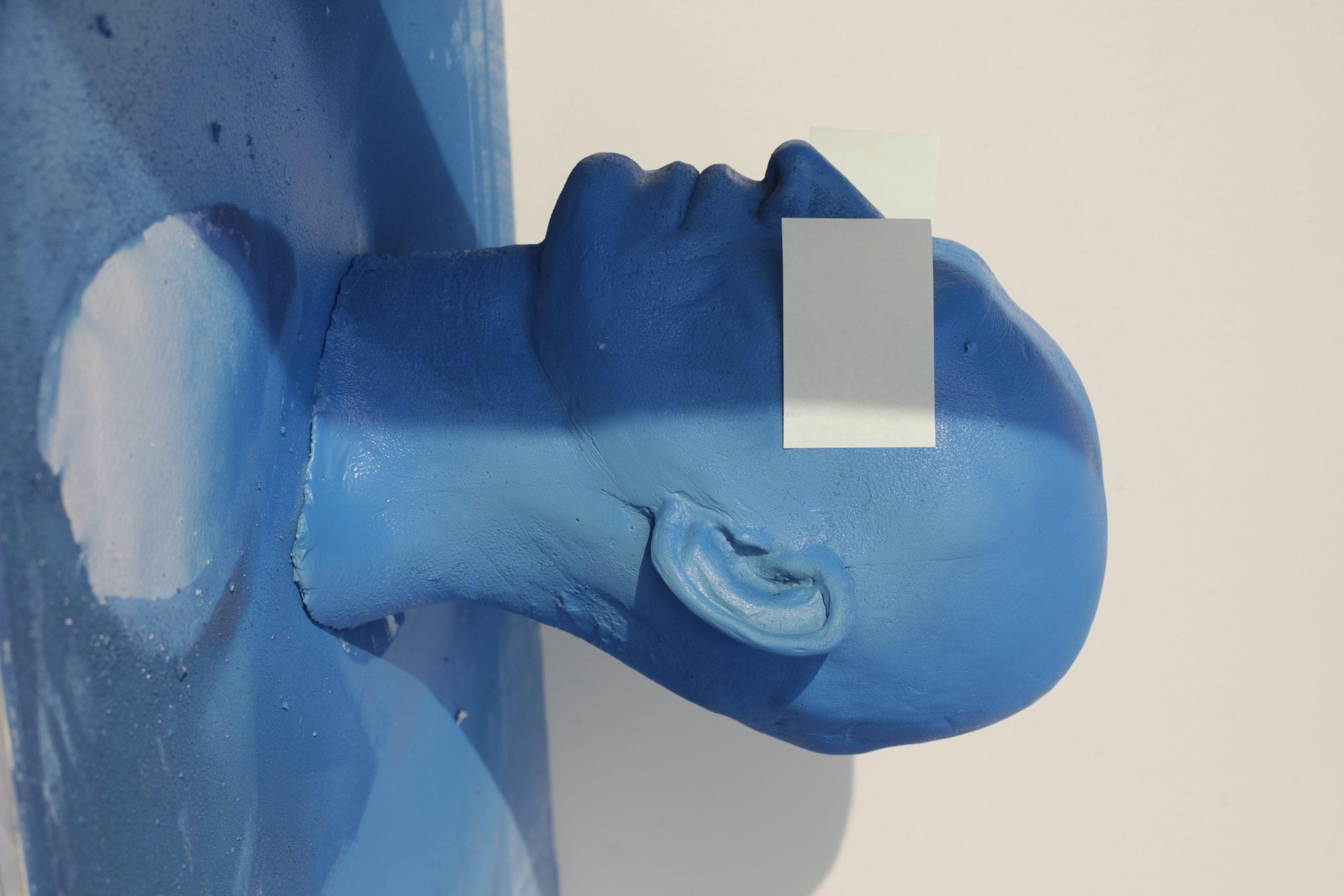

In his new book, Hardtack, Rahim Fortune compiles nearly a decade of work, blending documentary with personal history within the context of post-emancipation America. Through coming-of-age portraits that traverse survivalism and land migration, Fortune illustrates African American and Chickasaw Nation communities. As Taous R. Dahmani observes, the iconography of the American South is drawn between Fortune’s Hardtack and Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter, released only a few days after — both of which raise questions that serve to redefine ‘Americana’.

Taous R. Dahmani | Book review | 17 Apr 2024

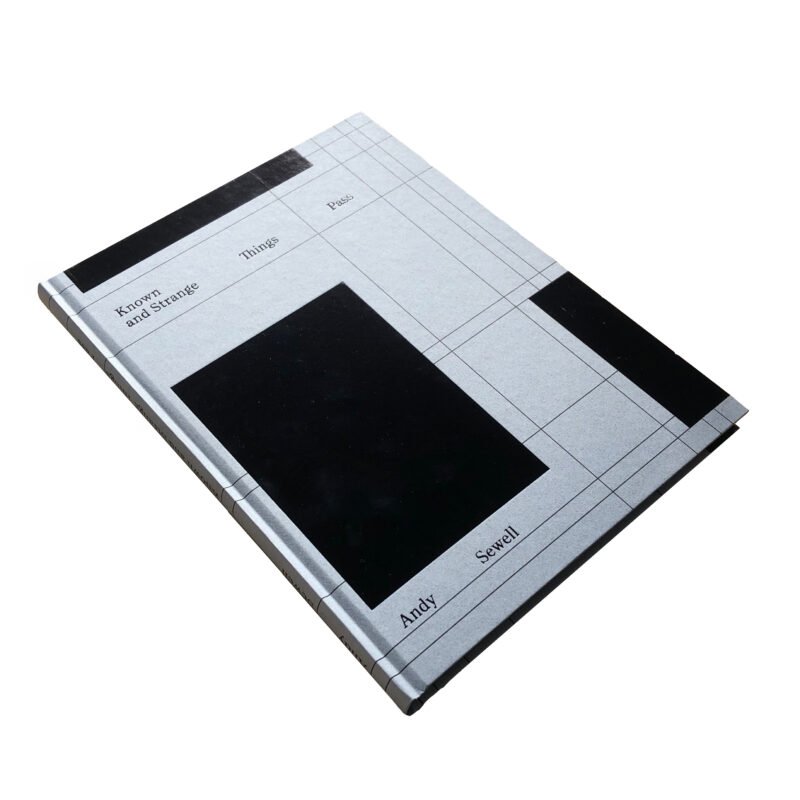

At the end of March, something very odd happened: Loose Joints dropped Rahim Fortune’s second photobook Hardtack, and, a few days later, Beyoncé released her eighth album Cowboy Carter. I can almost hear you – yes, you, reader – wondering, what’s the connection? Well, there are several. Firstly, it serves as the perfect soundtrack to look at Fortune’s photographs. As if sound was taking form. Beyoncé’s extensive 27-track list echoes Fortune’s 72 photographs; her lyrics resonating with his visual language. Both artists delve into the iconography and sound of cowboys, churches, southern mothers and daughters, rodeo, sashes and Fortune even closes his book with a “Queen Coronation”. Besides this serendipitous overlap, both artists also actively reclaim, redefine and adjust the notion of “Americana”. Wrapped in a denim-like cover, Hardtack speaks of a specific geography and moment: Texas today, the USA in the 2020s.

Beyond the anecdote of their shared Texas origins, both explore the history of the American South – one through music, the other through photography – connecting its past with its present. 2024 is a pivotal election year, with the southern states bearing a significant responsibility in shaping the country’s future (and, arguably, the world’s). Therefore, there is an urgent need to disseminate an alternative understanding or narrative of what the US might be. After all, the title of Fortune’s book, Hardtack, refers to an emergency survival food, made from flour, water and salt, signalling that we are in the midst of a critical juncture. At a time when states are banning books to erase chapters of US history, Hardtack feels like a welcomed defiance.

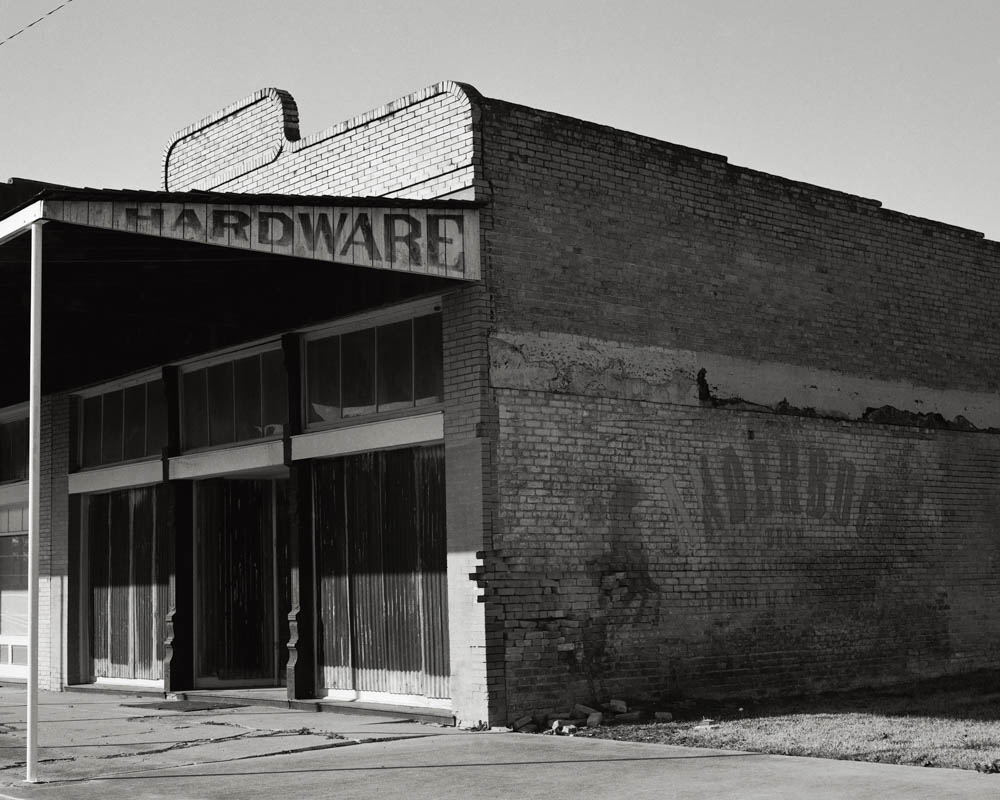

In her proudly made-in-America “country” album, Beyoncé embraces the soundscape of the southern states and her Black musical heritage, blending blues, soul, rock ‘n’ roll and gospel. Similarly, an incredible living encyclopaedia of American photography, Fortune quotes – or samples – his ancestors, from Walker Evans’s depictions of southern architecture to Roy DeCarava’s intimate portraits of Black life. Just as Beyoncé pays homage to Linda Martell, the first commercially successful Black female artist in country music, Fortune channels the social documentary style of Milton Rogovin, his portrayal of African-American communities akin to Earlie Hudnall Jr, and mirrors the political consciousness embodied by Consuelo Kanaga. Furthermore, Fortune examines Arthur Rothstein’s documentation of African-American families in Gee’s Bend, Alabama, originally captured for the Farm Security Administration and later featured in Richard Wright’s 12 Million Black Voices (1941). With Hardtack, Fortune engages in a self-conscious dialogue with photography’s history.

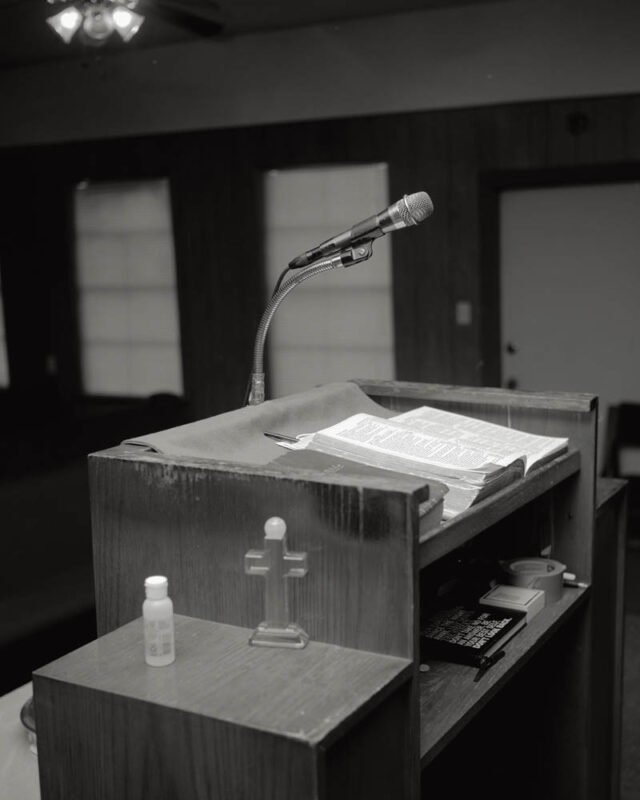

The parallel between music and photography transcends mere coincidence; its potency lies in their shared democratic practice and dissemination, but it also resonates with what Tina M. Campt described in A Black Gaze (2021) as a ‘broader commitment to understanding visual culture through its entanglement with sound, and highlighting the centrality of sonic and visual frequency to the work of Black contemporary artists.’ Already, in 2017, Campt beckoned us to listen to images, and more recently, she revisited the idea employing the concept of frequency to challenge ‘how we see’, adding that ‘the physical and emotional labour required to see these images gives us profound insights into the everyday experiences of Black folks as racialised subjects.’ Listening to Fortune’s Hardtack is to pick up on various stories and histories such as the legacy of Gee’s Bend quilts, crafted by descendants of enslaved individuals who toiled on cotton plantations. These local women united to establish the Freedom Quilting Bee, a worker’s cooperative that enabled crucial economic opportunities and offered political empowerment. As Imani Perry eloquently states in the book’s concluding essay: ‘What we know as Black Texas was birthed through captivity. This land has been a bounty; and also a burden.’ Fortune captures the architecture of past power and oppression – the grand plantation houses alongside the slaves’ huts –and the remnants of this legacy, showcasing what barely survives in the wake of US history. Beyoncé’ sings in “YA YA” (2024): “My family lived and died in America, hm / Whole lotta red in that white and blue, huh / History can’t be erased, oh-oh / Are you lookin’ for a new America? (America).” In “Night Ride Tracks, Archer, Florida” (2020), Fortune kneels down to capture the sunlight beaming on the old train tracks, which bear witness to the 1928 Rosewood massacre during the era of Jim Crow laws. In “AMEN” (2024), Beyoncé’s reminds her listener: “This house was built with blood and bone / And it crumbled, yes, it crumbled.”

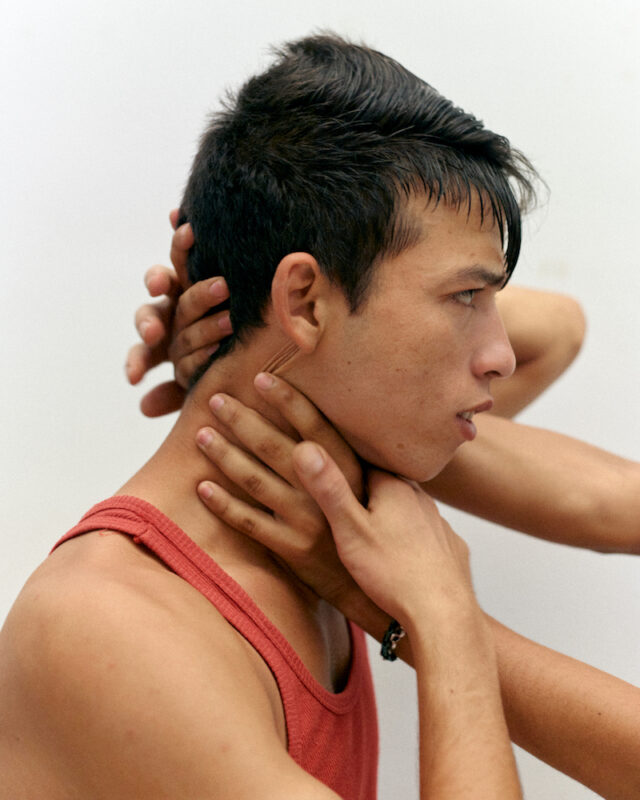

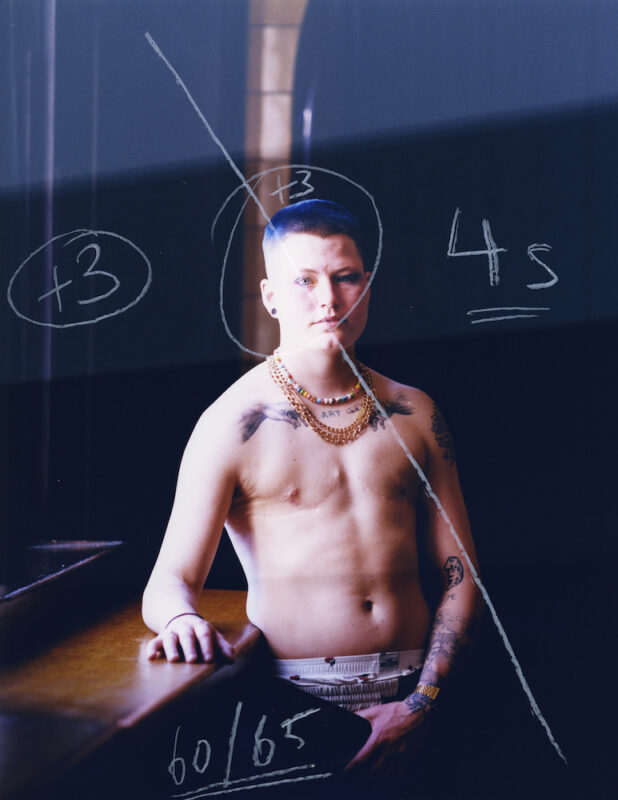

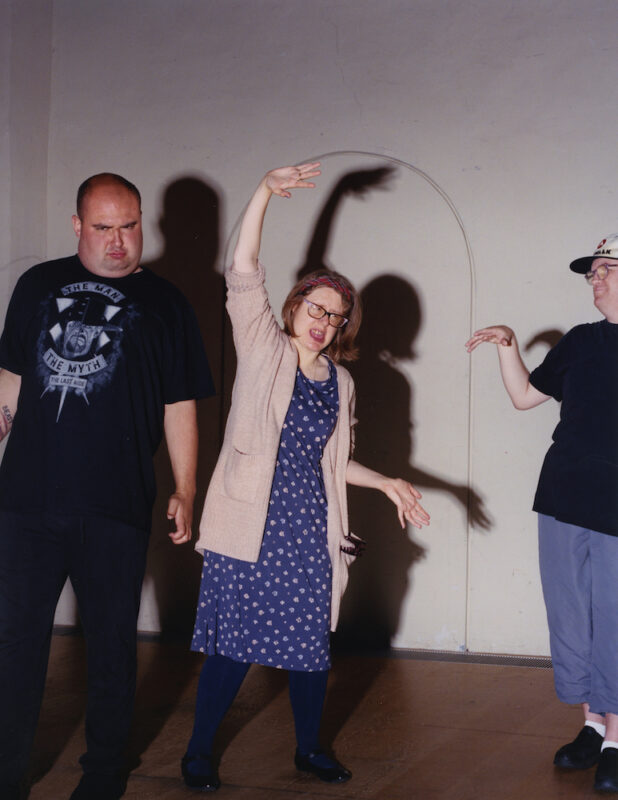

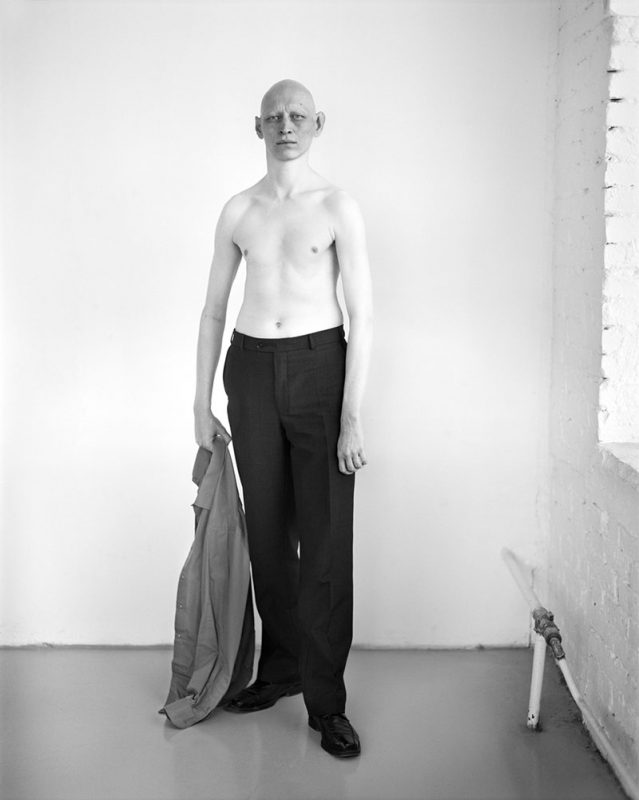

On the following page, Fortune presents a captivating portrait of his partner, Miranda, underscoring that his documentation of the American South is as personal as it is political. With roots in both the African-American and Chickasaw Nation communities, Fortune traverses rural towns that are close to his heart, pausing to engage in conversations with friends. Fortune embraces the formal conventions of documentary traditions whilst ushering us into novel sensations and uncharted emotional territories. Opening the book, we can almost grasp the wind, and, as we delve deeper, we feel the humidity of the Mississippi enveloping us, the scorching sun on the road casting its light upon each image. His photographs record what stands proud, what is forced to break, what disappeared but can still be traced. In Fortune’s photographs, people are praying, watching, playing, waiting, celebrating, caring and driving; leading an unremarkable life because ‘attending to the infraordinary and the quotidian reveals why the trivial, the mundane, or the banal are in fact essential to the lives of the dispossessed and the possibility of black futurity.”’ Texas also serves as the backdrop for Fortune’s personal grief – as depicted in his first book I can’t stand to see you Cry (2021) – and serves as a place where remembrance holds paramount importance, as evidenced by the tattooed dates of key life moments on his friend’s skin. Fortune’s Hardtack is a poignant tribute, both a requiem for those lost and a homage to those whose actions altered the course of history. Yet, it is also a celebration, capturing the essence of joy found in everyday moments and special occasions alike. It is this unique and delicate coexistence of remembrance and revelry that imbues Hardtack with its profound resonance, showcasing the depth of Fortune’s artistic maturity.♦

All images courtesy the artist and Loose Joints. © Rahim Fortune

Hardtack is published by Loose Joints.

—

Taous R. Dahmani is a London-based French, British and Algerian art historian, writer and curator. Her expertise centres around the intricate relationship between photography and politics, a theme that permeates her various projects. Since 2019, she has been the editorial director of The Eyes, an annual publication that explores the links between photography and societal issues. She is an Associate Lecturer at London College of Communication, University of the Arts London. Dahmani’s curatorial work was showcased at Les Rencontres d’Arles, France, where she curated the Louis Roederer Discovery Award (2022). Dahmani is set to curate two exhibitions at Jaou Tunis, Tunisia (2024).

Images:

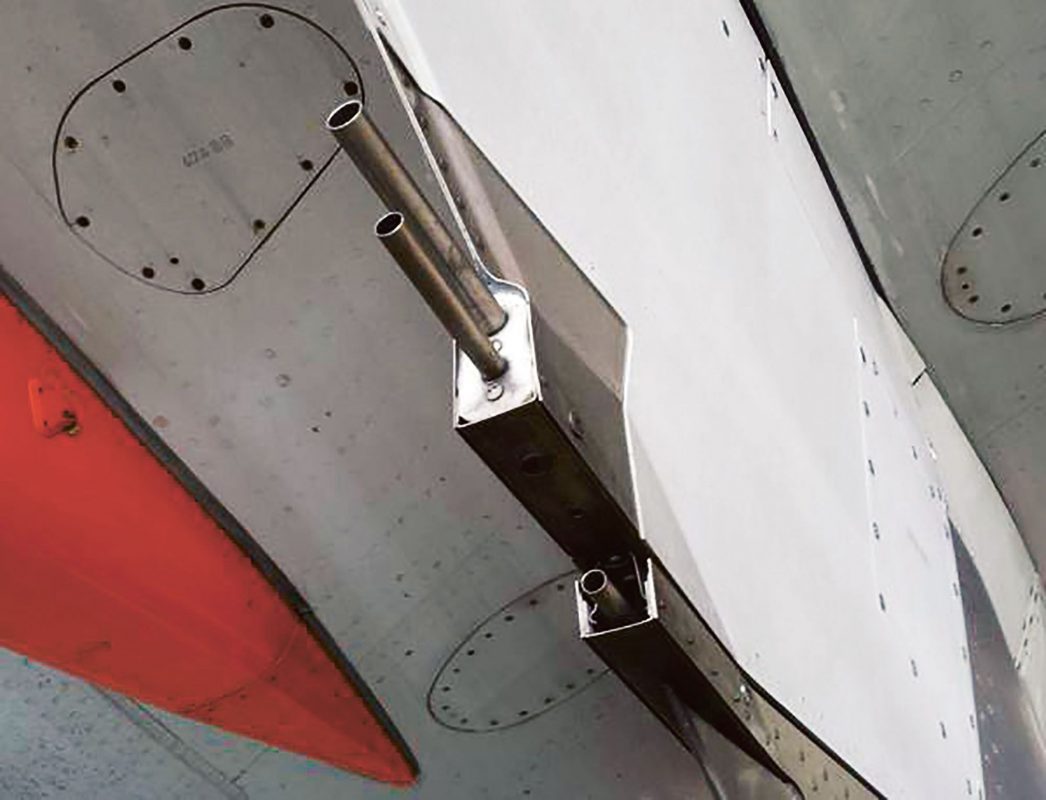

1-Rahim Fortune, Windmill House, Hutto, Texas, 2022.

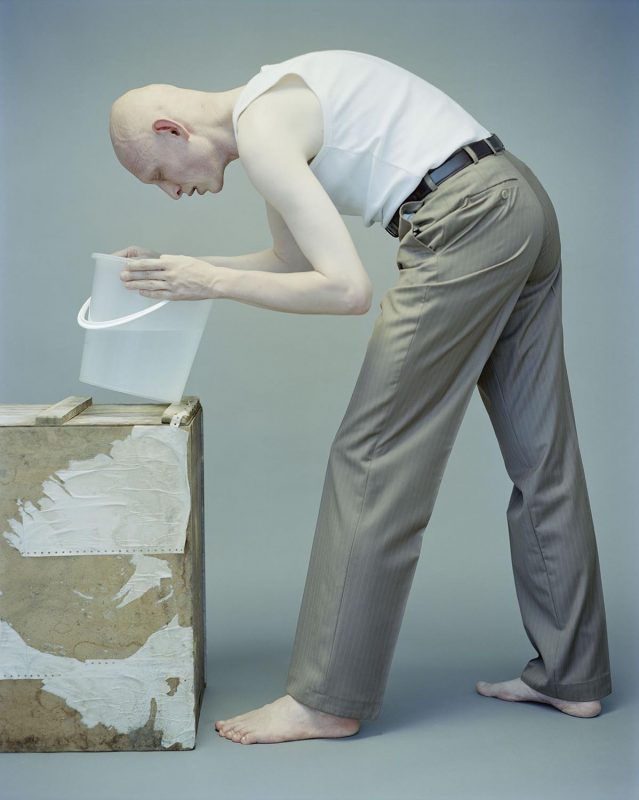

2-Rahim Fortune, Praise Dancers, Edna, Texas, 2022.

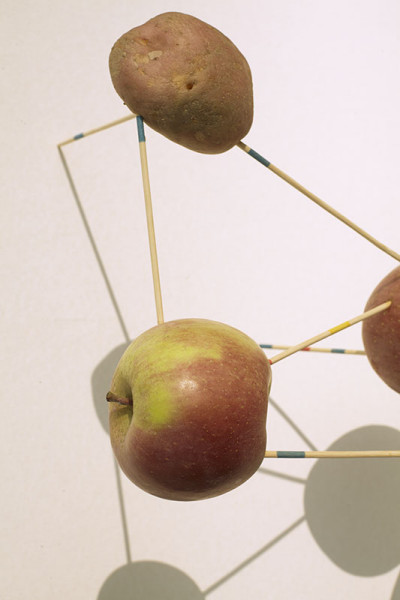

3-Rahim Fortune, Willies Chapel, Austin, Texas, 2021.

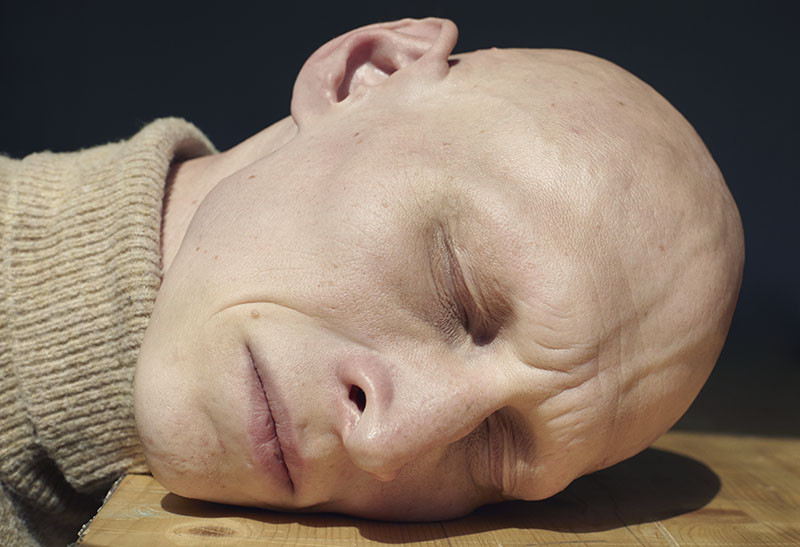

4-Rahim Fortune, Hardware, Granger, Texas, 2018.

5-Rahim Fortune, Highway I-244 (Greenwood), Tulsa, Oklahoma, 2021.

6-Rahim Fortune, Gas Pump, Selma, Alabama, 2023.

7-Rahim Fortune, Deonte, New Sweden, Texas, 2022.

8-Rahim Fortune, Ace (Miss Juneteenth), Galveston, Texas, 2022.

9-Rahim Fortune, Night Ride Tracks, Archer, Florida, 2020.

10-Rahim Fortune, Tinnie Pettway, Gee’s Bend, Alabama, 2023.

11-Rahim Fortune, VHS Television, Dallas, Texas, 2021.

12-Rahim Fortune, Abandoned Church, Otter Creek, Florida, 2020.