Exteriors – Annie Ernaux and Photography

Lou Stoppard (ed.)

Book review by Peter Watkins

Curator and writer Lou Stoppard adds visual repertoire to Annie Ernaux’s iconic Exteriors, originally published in 1993, through a new publication and exhibition titled Exteriors: Annie Ernaux and Photography — co-published by MACK and Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP), Paris. Recognising Ernaux’s iconic literary style – unapologetic, brave, and tender, inherently political and dedicated to amplifying marginalised voices – Stoppard sifted through 24,000 photographs, resulting in a photo-book that captures the rituals of everyday life, in a way not so mundane, as Peter Watkins writes.

Peter Watkins | Book review | 21 Mar 2024

Annie Ernaux’s intimately autobiographical writing is much like the dull ache of an old injury, reminding the body, through its persistence, of its entanglement in the world over time. She writes for the sake of memory and forgetting, and has been prolific in her output since the mid-1970s, earning a Nobel Prize for Literature along the way. Her writing is unapologetic, unembarrassed and tender in its bravery. She has spoken of her work as being inherently political, driven by a genuine desire to give voice to the underrepresented, namely the working class, in acutely observed reflections from her everyday encounters. Her work is paired back, unadorned, with no room for hyperbole. A pioneer of autofiction, she doesn’t seem to suffer from the indulgences and excesses that sometimes accompany the genre.

Ernaux has spoken of photography as acting as a catalyst for her writing, but it’s ordinary, as opposed to extraordinary, photographs of people that are meaningful to her. She uses photographs as an aide de memoire, and has suggested that: ‘The photograph is nothing other than stopped time. But the photograph does not save. Because it is mute. I believe on the contrary that photography increases the pain of passing time. Writing saves, and cinema.’ In her book The Years (2008), the opening passages come to us like abrupt flashes of memory; fragmentary, and incomplete, but bright and image-like. These lines reveal perhaps most clearly, both her directness and the umbilical bond between photography, memory and language, as well as the existential fear of forgetting and being forgotten: ‘All the images will disappear. […] Everything will be erased in a second. […] We will be nothing but a first name, increasingly faceless, until we vanish into the vast anonymity of a distant generation.’

Upon reading Exteriors (1996), Lou Stoppard contacted Simon Baker, Director of the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) in Paris, surprised that there hadn’t previously been a major institutional collaboration between Ernaux’s writing and photography, particularly given the building attention around her life’s work, not to mention the photographic claims her writing has made, as so explicit in Exteriors. Stoppard was promptly invited to spend a month going through some 24,000 photographs and 36,000 photobooks that make up the MEP’s collection. Her selections represent some of major names in documentary photography such as William Klein, Luighi Ghirri, Ursula Schulz-Dornberg, Claude Dityvon and Daido Moriyama. The photographs were made in the mid-20th century onwards and depict almost always people, built-up environments and ephemeral encounters in the city.

Post-war photography of this kind moved us away from a prescribed reading of the image to a multi-layered, subjective and ultimately equivocal vision of the world – uncertain images for uncertain times – and, in that sense, the pairings seem apt, if sometimes a little on the nose. Stoppard herself concedes these ‘moments of visual coincidence’ of course occur, a near-impossibility to avoid perhaps, given the familiarity of the imagery evoked in Ernaux’s writing. She also didn’t want to focus on the grand boulevards of Paris, on Eugène Atget, or the traditional idea of the flâneur, but, rather, on a more universal vision of the everyday, the language of advertising and the rituals of life. Indeed, to do otherwise wouldn’t have made sense, given Ernaux’s politics and focus. As Stoppard points out: ‘To compare Ernaux’s writing to photography is a project that is impossible to divorce from questions of class. Seeing is a privilege. Photographing is even more of a privilege.’

The inference of pairing Ernaux’s originally slim 74-page Exteriors with this curated selection of photographs from the MEP’s collection is to cement some of the photographic associations we already hold dear to her work, but perhaps also to examine this lesser-known publication in photographic terms – extending readings, teasing out connections and re-examining the question of how literature and photography can coexist, and to what end. Stoppard makes headway in this regard in her accompanying essay “Writing Images”, found at the end of Exteriors – Annie Ernaux and Photography, jointly published by MACK. Here, she attempts to contextualise Ernaux’s photographic intentions not only by examining Exteriors, but also by reaching back within the wider context of her work.

Over the decades, Ernaux’s writing has fearlessly examined, amongst others, themes such as the interior life, identity, women and the body, shame, nascent sexuality, illegal abortion, female sexuality, relationships, grief and the perception of time. Unwavering in her pursuit, these themes have played out somewhere between Ernaux’s subjective personal experiences, read within the wider societal and political movements of the times.

If Ernaux’s work often leans towards the exploration of interiority, a pursuit nearing claustrophobia in its intensity, then Exteriors, in some respects, represents a literal break, turning itself outwards to the surface of things. The book, in its original form, is made up of journal entries written over the course of seven years, between 1985 and 1992, and mostly in-and-around Cergy-Pontoise, one of five suburban “new towns” surrounding Paris built up in the 1960s, a place she has vehemently rejected as being simply categorised as a non-lieux or non-place. This is where she has written much of her work, a place that is integral to her writing, a place she calls home: ‘A place suddenly sprung up from nowhere, a place bereft of memories […] A place with undefined boundaries.’

These are observations from Ernaux’s adopted home, the neighbourhoods she moves through, from the dentist’s waiting room to the RER suburban train or visits to the Hypermarket. These are the banal spaces of the everyday, observed matter-of-factly, sharply. This is a real, visceral vision of the periphery, away from the charm and clichés of Paris. For Ernaux, these everyday spaces are imbued with sociological and psychological substance, with ‘as much meaning and human truth as the concert hall.’

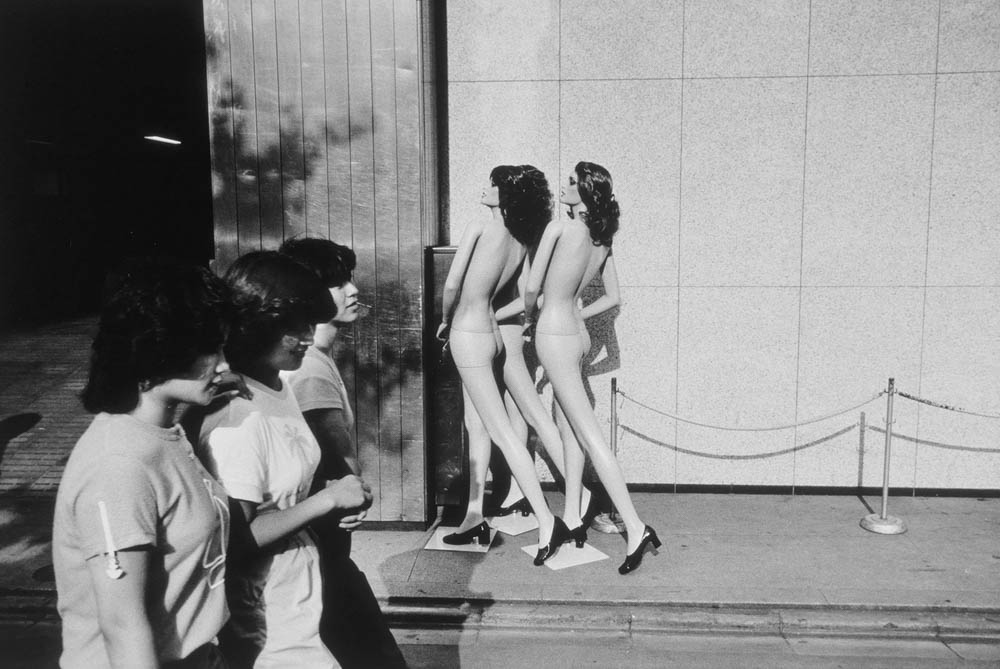

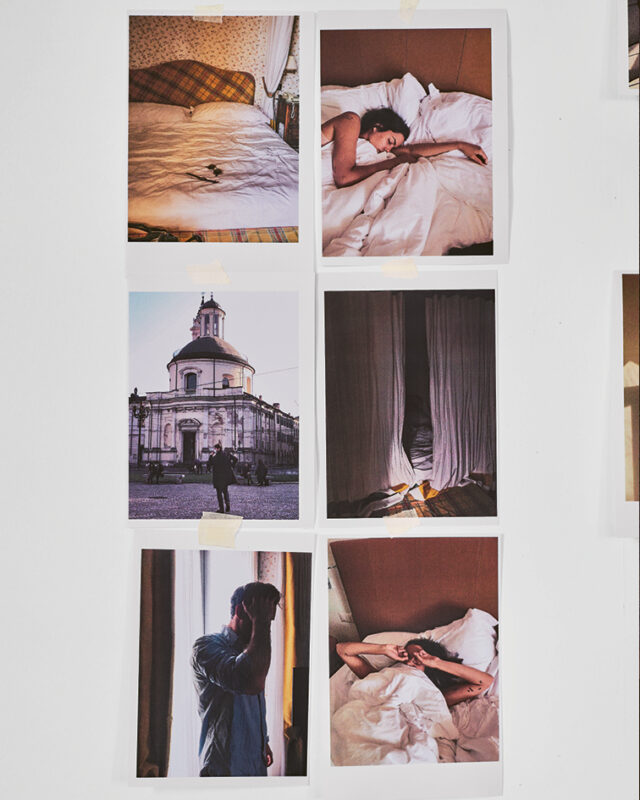

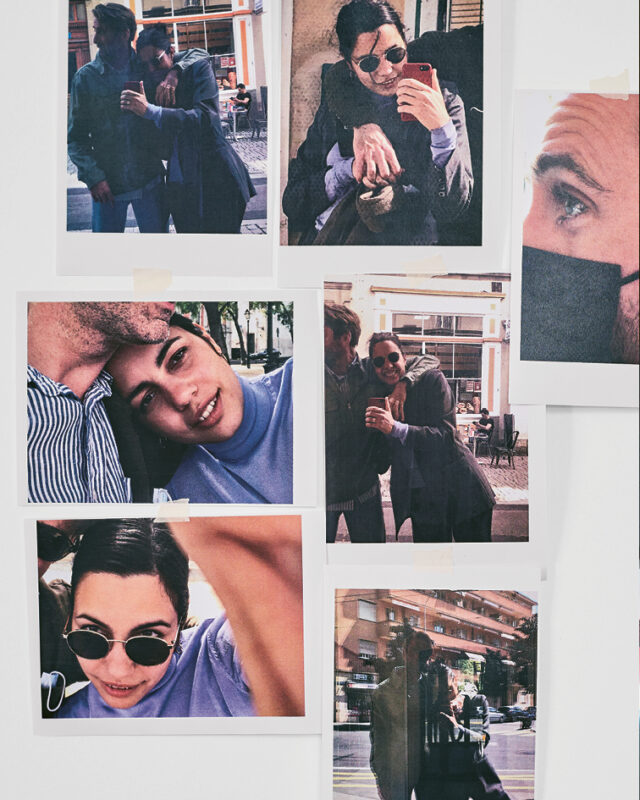

The images serve to punctuate what is about a third of Ernaux’s book, which is broken up chronologically, and slipped formally between the photographs, inevitably encouraging associations through juxtaposition. The text and images evoke one another, but are not intended as captions or illustrations. Rather, they are offered equal weighting on the page. The images weave between eras and geographies, almost all depicting people, or signs of humanity, pointing towards the universal experience of the city, where, for the first time in history, more than half of the world’s population currently dwells. The photographs, as well as the text, attest to the observational faculties of their authors, captivating and complicating our attention, without ever really being too prescriptive or dogmatic in their associations.

In her interview with the Louisiana Channel, Ernaux describes her work as factual, and restrained of feeling. She writes in Exteriors: ‘I have sought to describe reality as though through the eyes of a photographer… To preserve the mystery and opacity of the lives I encountered.’ But with that comes a tireless curiosity, presented to us by an omnipresent Ernaux, who has the imagination to transform these all too familiar encounters from daily life into something of real vibrancy and fortitude, and, of course, there’s plenty of feeling built into that act. The same could be said of many of the photographers whose work make up the pages of this book. The people encountered come to us as protagonists of their own stories which we glimpse, move through and then beyond, perhaps inviting us to consider the increasingly unequal social hierarchies pronounced and laid bare in the shared urban environments that we presently occupy, in turn allowing us to reflect on how they might be reimagined. ♦

All images courtesy the artists, MACK and MEP.

Exteriors – Annie Ernaux and Photography runs at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, France, until 26 May 2024. The accompanying book is published by MACK.

—

Peter Watkins is an artist and educator based in Prague, Czech Republic. Watkins received his MA in Photography at the Royal College of Art in 2014, and has since exhibited his work internationally, receiving several awards for his ongoing practice. His work is held in the collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, and Fotomuseum Winterthur, Switzerland. His book The Unforgetting was published by Skinnerboox in 2020. He is currently Associate Lecturer at Prague City University.

Images:

1-Claude Dityvon, 18 hears, Post de Bercy, Paris (18 hours, Bridge of Bercy, Paris), 1979. Gelatin silver print, MEP Collection, Paris. Acquired in 1979. From Exteriors: Annie Ernaux and Photography (MACK and MEP, 2024). Courtesy the artist, MACK and MEP.

2-Dolorès Marat, La femme aux Gants (Woman with gloves), 1987. Fresson four-colour pigment print, MEP Collection, Paris. Acquired in 2006. From Exteriors: Annie Ernaux and Photography (MACK and MEP, 2024). Courtesy the artist, MACK and MEP.

3-Dolorès Marat, Neige à Paris (Snow in Paris), 1997. Fresson four-colour pigment print, MEP Collection, Paris. Acquired in 2001. From Exteriors: Annie Ernaux and Photography (MACK and MEP, 2024). Courtesy of the artist, MACK and MEP.

4-Hiro, Shinjuku Station, Tokyo, 1962. Gelatin silverprints, MEP Collection, Paris. Gift of the Elsa Peretti Foundation in 2008. From Exteriors: Annie Ernaux and Photography (MACK and MEP, 2024). Courtesy The Estate of Y. Hiro Wakabayashi, MACK and MEP.

5-Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, Ploshchad Vosstaniya – Uprising Square, 2005. Photogravure, MEP Collection, Paris. Gift of the artist in 2020. From Exteriors: Annie Ernaux and Photography (MACK and MEP, 2024). Courtesy the artist, MACK and MEP.

6-Janine Niepce, H.L.M. à Vitry. Une mère et son enfant (Council estate in Vitry. A mother and her child), 1965. Gelatin silver prints. MEP Collection, Paris. Acquired in 1983. From Exteriors: Annie Ernaux and Photography (MACK and MEP, 2024). Courtesy the artist, MACK and MEP.

7-Marie-Paule Nègre, Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris (Luxembourg Garden, Paris), 1979. Pigment inkjet print, MEP Collection, Paris. Gift of the artist in 2014. From Exteriors: Annie Ernaux and Photography (MACK and MEP, 2024). Courtesy the artist, MACK and MEP.

8-William Klein, Finale de l’élection de Miss France, entourée de Jean-Pierre Foucault et Mme de Fontenay (Final of Miss France contest, surrounded by Jean-Pierre Foucault and Mrs de Fontenay), 2001, from the series PARIS + KLEIN. C-type prints, MEP Collection, Paris. Acquired in 2002. From Exteriors: Annie Ernaux and Photography (MACK and MEP, 2024). Courtesy William Klein Estate, MACK and MEP.

9-Bernard Pierre Wolff, Shinjuku, Tokyo, 1981. Gelatin silver print, MEP Collection, Paris. Bequest from the artist in 1985. From Exteriors: Annie Ernaux and Photography (MACK and MEP, 2024). Courtesy the artist, MACK and MEP.

10-Daido Moriyama, Untitled, 1969. Gelatin silver print, MEP Collection, Paris. Gift of Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd. in 1995. From Exteriors: Annie Ernaux and Photography (MACK and MEP, 2024). Courtesy Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation, Akio Nagasawa Gallery, MACK and MEP.