Marton Perlaki

Bird, Bald, Book, Bubble, Brick, Potato

Interview by Tim Clark

“A picture has the ability to mislead the mind, opening a door to alternative narratives that exist within the viewer’s subconscious. I wish to access these moments of subjectivity and navigate the viewer towards a game of associations.” So says Marton Perlaki, a Hungarian artist whose ongoing series Bird, Bald, Book, Bubble, Brick, Potato has now made the journey into book form entitled Elemer, published by Loose Joints.

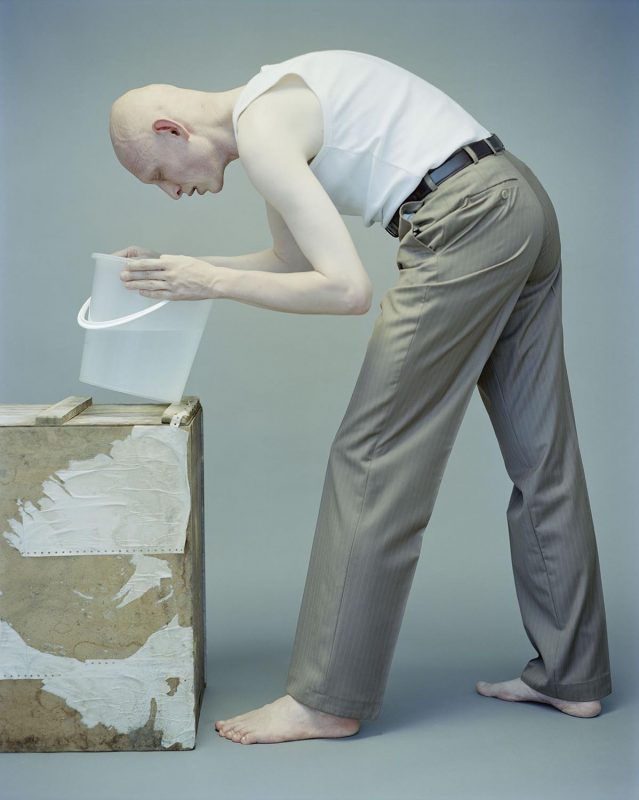

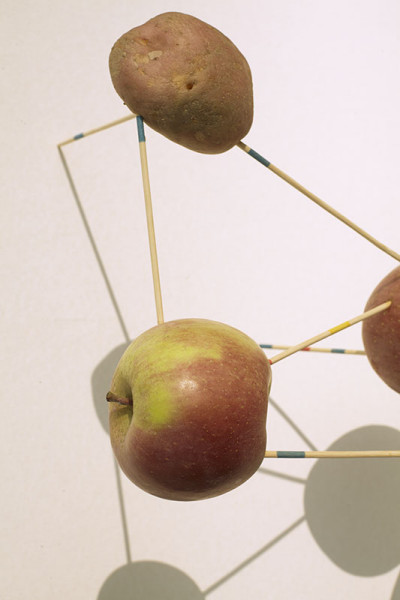

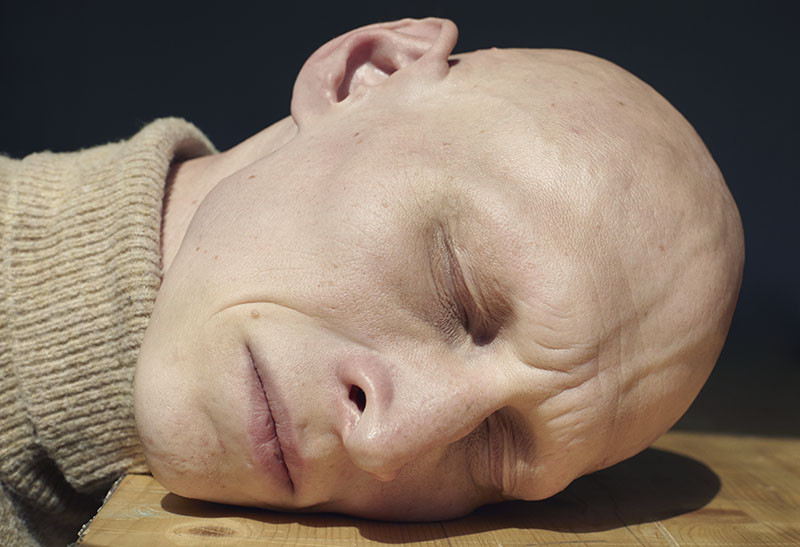

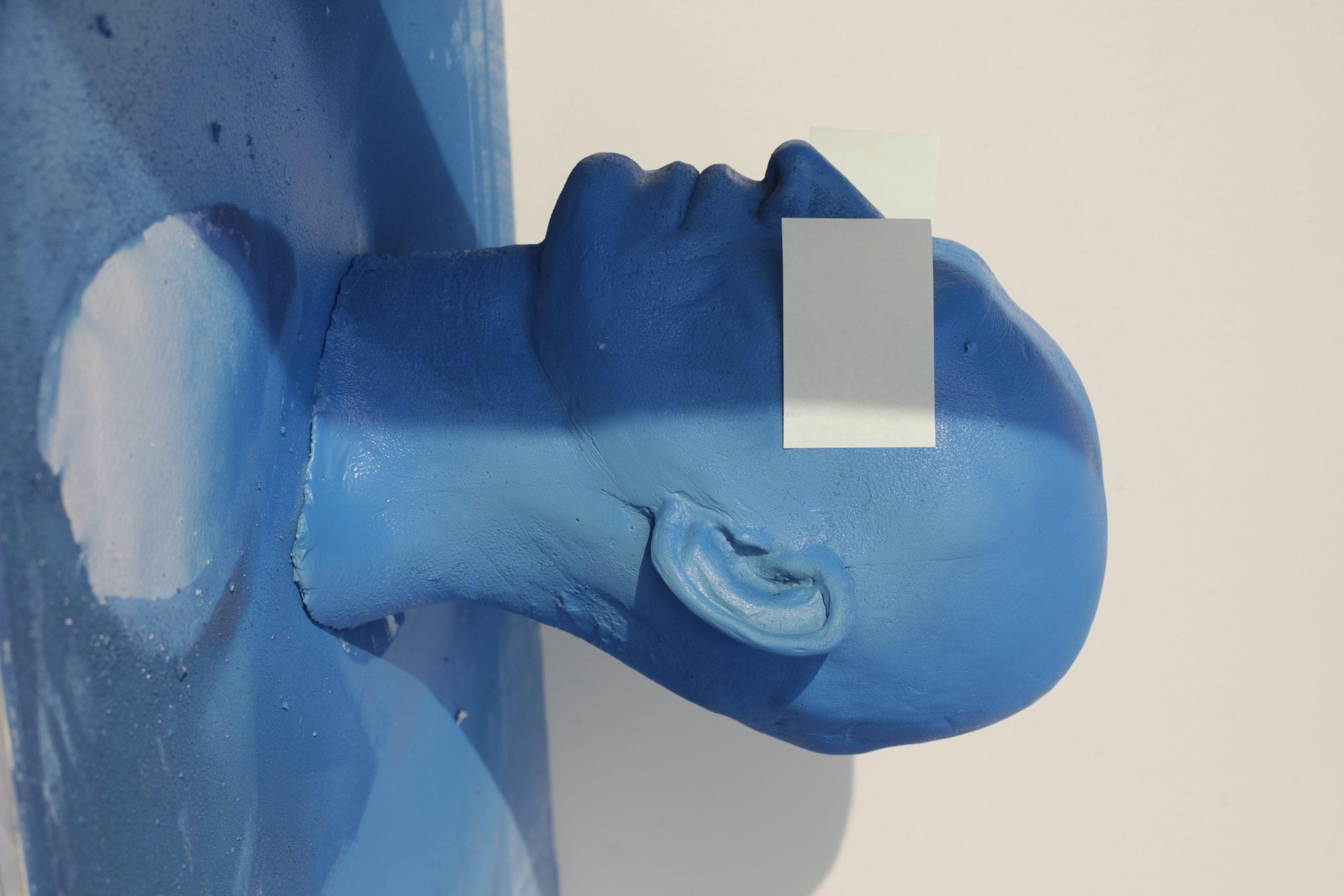

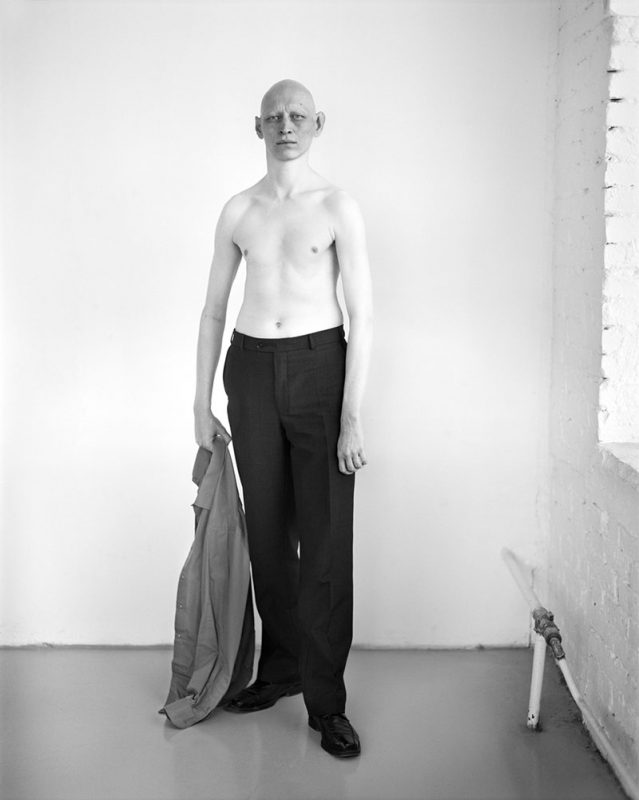

His intriguing publication presents a rich array of seductive and sardonic imagery, drawing principally on two main photographic genres – still life and portraiture. Perlaki’s process involves carefully planning and creating unique arrangements, wherein he makes everyday objects and scenarios undergo an absurdist upheaval. Some images show a pale, macabre-looking man – Elemer – as he strikes equally unusual poses or exhibits various states of uneasiness. Some show stuffed birds wrapped in string, their eyes pierced with needles while others reveal constellations of bubbles delicately emerging from laboratory apparatus – these are but a few examples of the jarring mix of views and subjects that chafe on our mind. His work summons the idea that discontinuity and dislocation can be powerful strategies to defy viewer expectations and thus force a reflection on photography’s randomness and incessancy, as well as its ability to control the disorder of the natural world through repetition, juxtaposition and artifice.

“I was always drawn towards variety in a series and never really interested in linear story telling,” Perlaki says. “I find it important to make the viewer participate and invite him/her to make connections between seemingly unrelated images. Everyone can create their own personal narrative which seems like a fun process to me.”

Interspersed with his own photographs are a handful of pictograms of mundane items, both natural and man-made, including a balloon, a lock and key, a vice, a bucket, a garden hose, a potato, a worm and a brush. Deadpan yet also playful in tone, these functional illustrations serve as visual and symbolic equivalents to his imagery, often precipitating the appearance of certain motifs and manifold shapes that give rise to meaning – or at least short-lived thematic runs.

“The whole project started as a stream of ideas,” Perlaki explains. “The trigger was a series of cards that companies used to include in packs of cigarettes. They were actually called ‘cigarette cards’, in the first half of the century. The cards would display useful household tips. On first glance the images look silly and nonsensical but when you flip them over and read the corresponding text the pictograms suddenly make sense.”

Providing both senseless and factual situations, Perlaki conjures up visual poems or private performances, yet records only one remote moment, such is the nature of photographic capture. On the surface of things, his photographs are relatively simple and innocent – childish even. Perhaps photography, given that it is relatively naïve and young compared to the other visual arts, is really a childish medium after all. At least this is what Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa posits in his afterword to the book. The writer goes on to encourage us to consider photography as childish in its dogged determination to record nothing more than the instant on which its attentions are focused. Childish in its disgust and delight, clarity and uncertainty, or for swaying from the fleeting to the ineffable. He surmises: “Photography’s capacity to register anything to which it can be exposed is similar to a child’s capacity to treat dog shit and diamonds with an equal measure of fascination.”

Indeed, Perlaki’s results are equal parts capricious and witty, menacing and hallucinatory. But, above all, it is the human element that finds its way into the imagery via the portraits that is key to both heightening and further complicating the sense of disquiet. This obviously relates to Perlaki’s specific choice of model, who, despite his outward impression, is in fact a happy family man and a teacher living and working in Szolnok, Hungary. What is evinced here is the notion that the reflection of reality reveals nothing about reality. The photograph is at once a portrait of Elemer and not Elemer. It does not disclose anything about the individual. He is a person with an entire life, with dreams, desires, worries and fears – complexities that we will never know from the photograph.

If, as Bertolt Brecht famously remarked, “photography is the possibility of a reproduction that masks the context……So something must be built up, something artificial, something posed,” then Perlaki’s work shares a kinship with this sense of photography setting out to experiment and instruct, exemplified by his photographic constructions and flagrant theatricality. “My idea was to use one character throughout the series and I was struggling to find the right fit when I accidentally came across a photograph of him while I was browsing on Facebook,” he explains. “Elemer’s peculiar appearance in these staged moments adds a mystical quality to the series. He is simultaneously sculptural and enigmatic, which for me was a perfect combination for the series.”

As he moves and appears before the camera, Elemer’s gestures reveal nothing of his essence, but reveal to us the charm of a gesture – the type Milan Kundera obsessed over in his seven-part novel from 1968, Immortality. Establishing his characters, the writer states that a gesture cannot be regarded as the expression of an individual, as his creation (because no individual is capable of creating a fully original gesture, belonging to nobody else), nor can it be considered as that person’s instrument. On the contrary, it is “gestures that use us as their instruments, as their bearers and incarnations.”

Ultimately, Elemer and his gestures become just another one of the photographer’s props. He is part of Perlaki’s inventory of objects, collected and composed through photographic form – their particular sequencing and repetition across the series offering a focus that is restless and multiple. In accumulative effect, arrays of images either contradict or compliment one another in a critical or reflexive way – similar to Brecht’s insistence on the built up – all the while embodying a nominal relationship to the world. After all, a bird is to bald, as book is to bubble, as brick is to potato, is what Perlaki’s art suggests and provokes. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist and Webber Represents. © Marton Perlaki

Excerpts of this interview were originally published in the FOAM Talent issue 2015 and have been reproduced with kind permission.

—

1000 Words Julia Margaret Cameron: Influence and IntimacyGathered Leaves: Photographs by Alec SothPeter Watkins: The UnforgettingRebecoming: The Other European TravellersFOAMTIME LightboxThe TelegraphThe Sunday TimesPhotoworksThe British Journal of Photography