Mathieu Pernot

Les Gorgan 1995-2015

Essay by Natasha Christia

A highlight of this year’s Les Rencontres d’Arles, Mathieu Pernot’s Les Gorgan 1995-2015 welcomed visitors with respectful silence. Hosted under the high ceilings of la maison des peintres, a new venue located near the calm premises of the village cemetery, the exhibition is presented as a multi-layered narrative comprising ten murals each dedicated to members of the Gorgan, a small Roma family from Arles living along the shores of Rhône. Spanning over two decades, it told the story of their individual destinies, and through it, the journey of photographic imagery that has accompanied them.

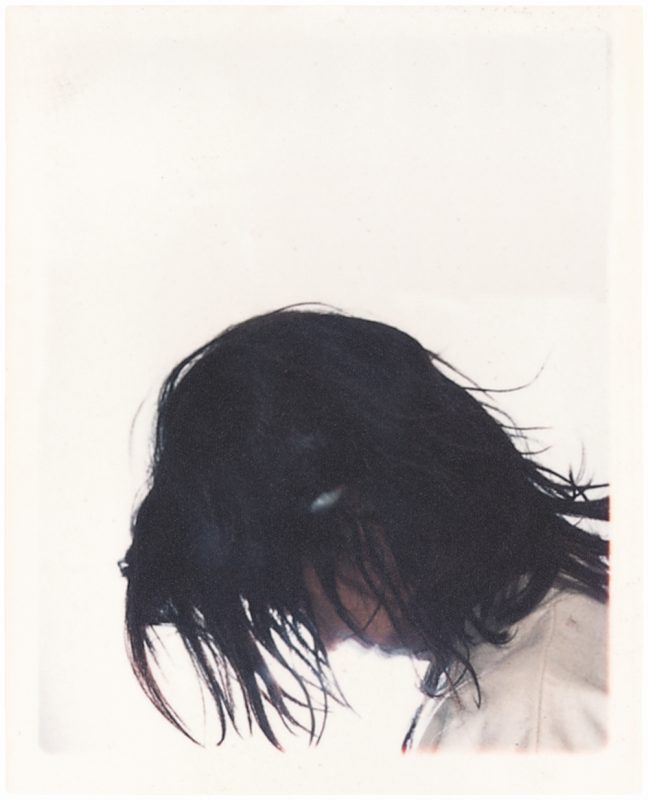

Importantly, Pernot’s gorgansiene universe created a precise and honest statement beyond visual and conceptual effects. In comparison to the noisy theatricality of Roger Bailen’s installation in the adjacent space wherein photography was unceasingly striving to find its place in the misty waters of contemporaneity, there was nothing redundant or unnecessary in it. Stretching exclusively across photography’s genres and practices – black and white portraiture, mug shots, Polaroids, iPhone and vernacular images – it was in many ways a slap in the face. A straightforward confrontation with photography and its evolution over the last twenty years, a prosaic testing of its normative modes, and, above all, an involuntary and yet consistently ruthless reminder of what straight images can do.

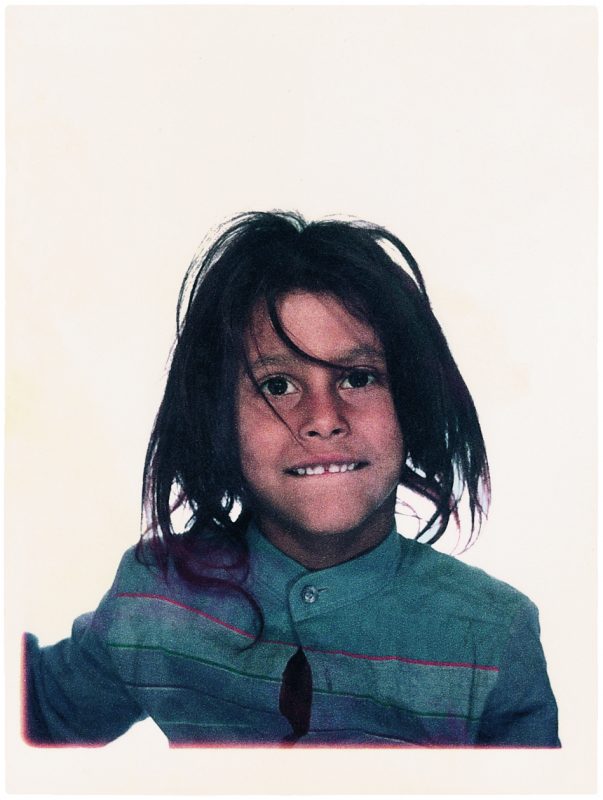

It was back in 1995, while still a student at L’École supérieure de la photographie d’Arles, when Mathieu Pernot first came across a group of gypsy kids in the area surrounding the village’s railway station. Pretty much everything has happened since his introduction to the whole family and the debut show of The Tsiganes (1995-1997) at Les Rencontres d’Arles in 1997. Seasons have alternated, kids have become teenagers, teenagers parents and former adults grandparents. Life has bestowed upon the Gorgan joys, farewells and irretrievable losses. Likewise, he ‘who once met those people as a photographer’ has found himself involved in a long-lasting relationship with them. By 2001, when Pernot left Arles for Paris, he had become godfather to their children, had inquired into the family history that extends over one century, and had funded Yuk, an association committed to the education and integration of gypsy children in the local community.

In the years that followed up until to the present, Les Gorgan has been continually revisited and naturally reflects how Pernot’s conceptual approach and strategies has evolved. The development of the project incorporated various chapters, distinct ideological and symbolic layers and diverse points of view. Over the course of two decades, the artist published different bodies of work in the form of seemingly disconnected series, yet all parts of the same puzzle. Unconsciously he was building a cartography, a universe, a whole.

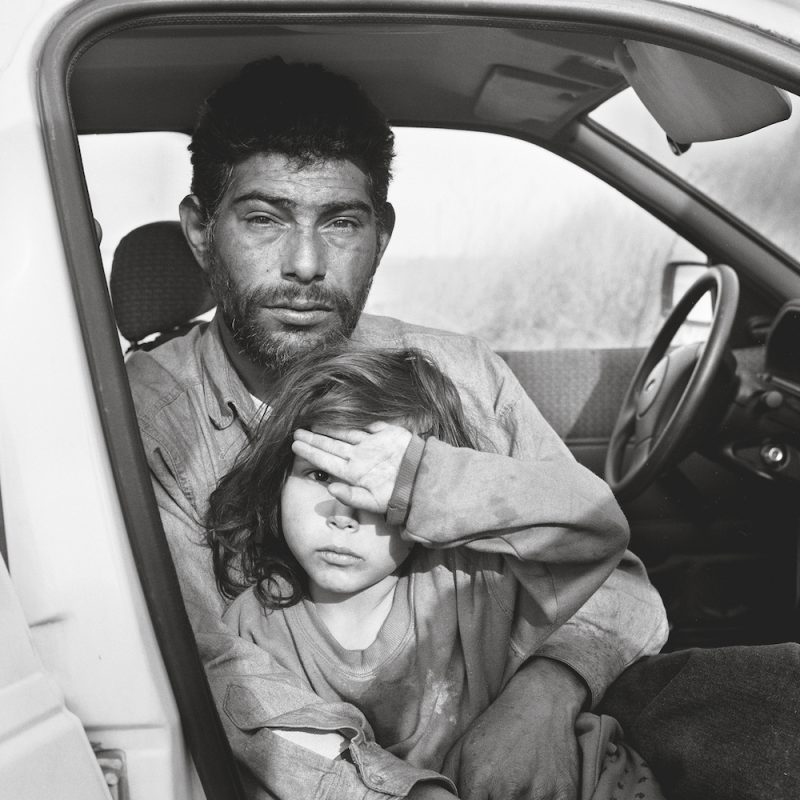

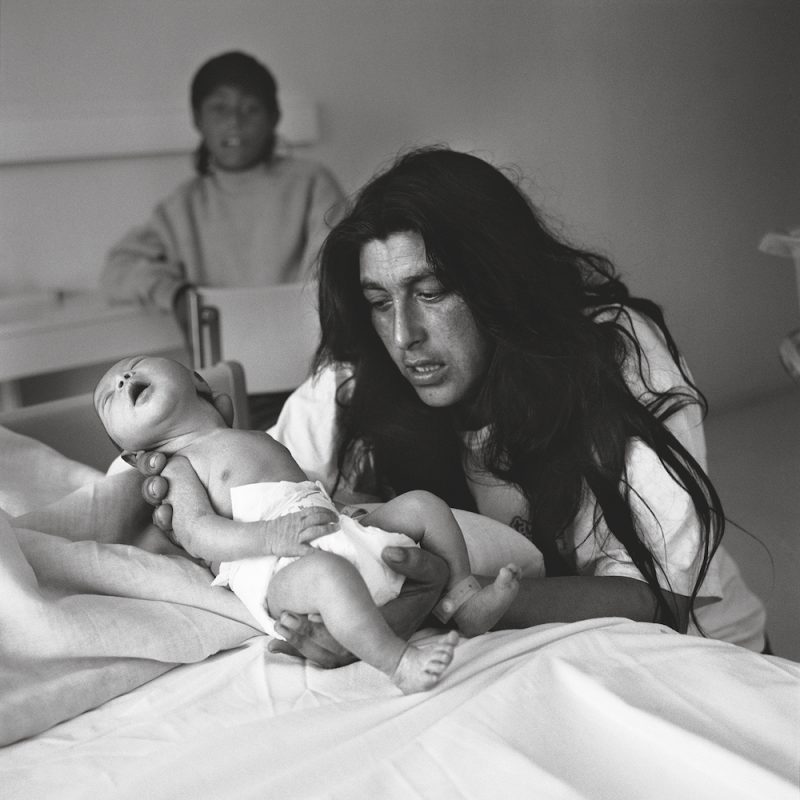

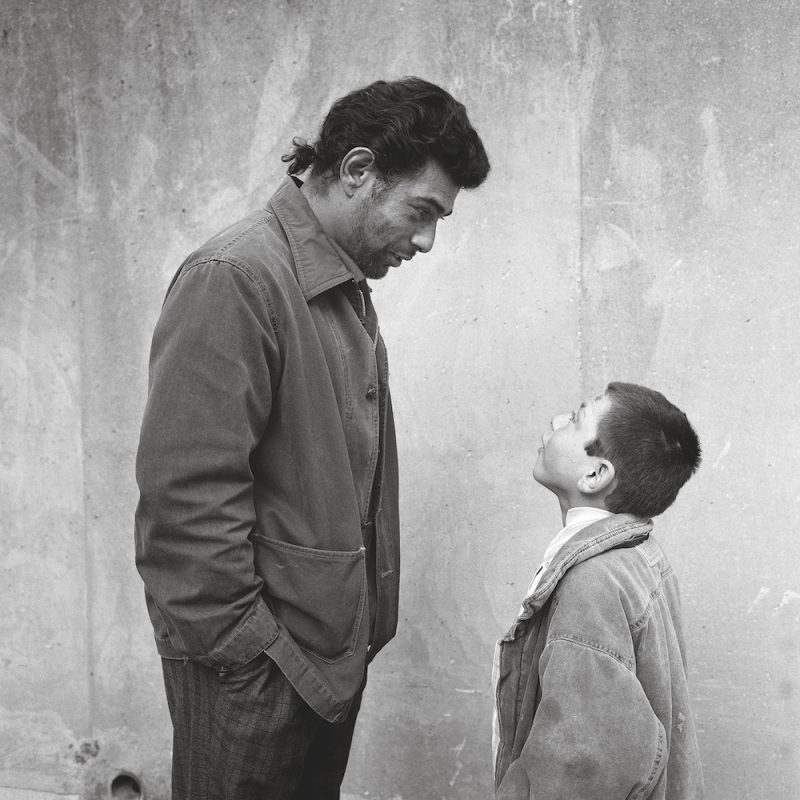

The current assemblage, as displayed in Arles, is a remixed version after Pernot’s reunion with the family in 2012, a programmatic dismantling of the preexistent bodies of work that have been reedited and shaped anew. Many different projects and years have been spliced together in a new formulation. From the early children portraits in Tsiganes (1995-1997) – fusing a documentary approach at the crossroads with humanist photography and the detached observational documentalism akin to Walker Evans – to correspondent mug shots in Photo booths (1995-1997) in the tradition of anthropometric portraits; from their penitentiary choir, as teenagers, outside the prison of Avignon in The Shouters (2001-2004), to the whole family watching the deceased Rocco’s caravan burning in Fire (2013), photography here appears closely attached to a changing liquid reality.

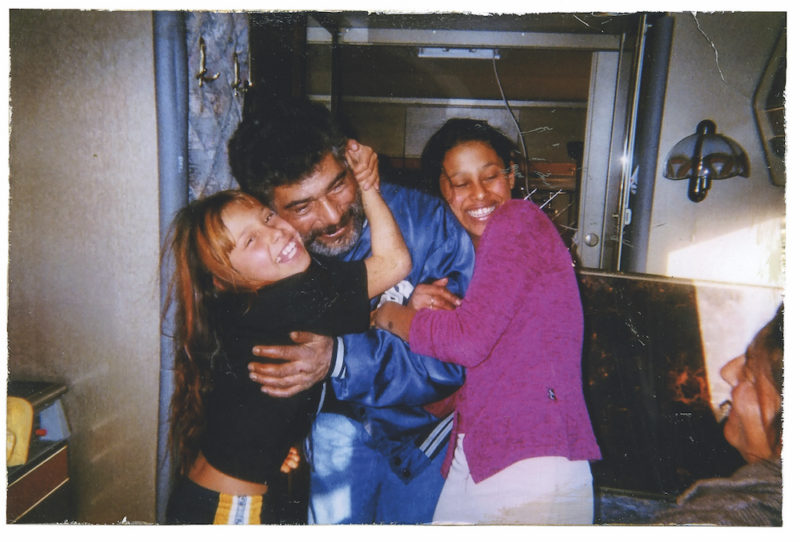

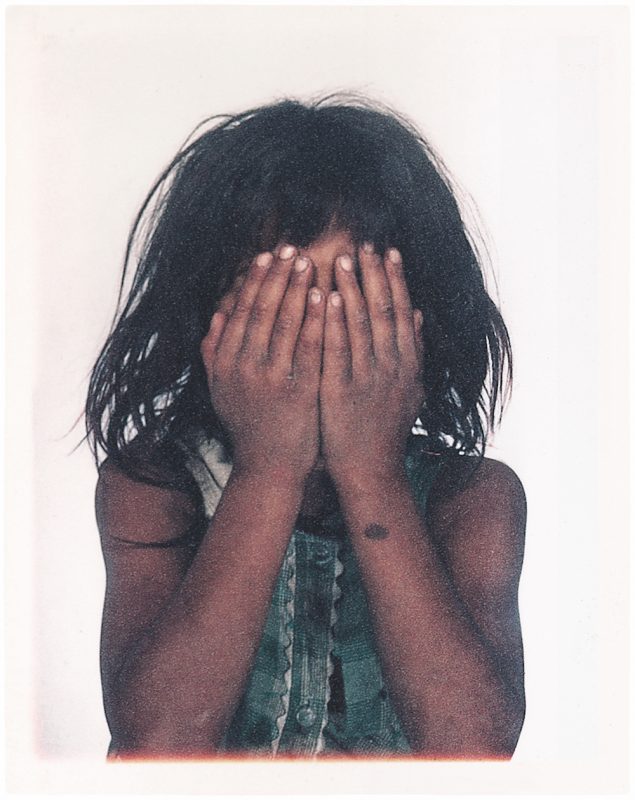

Similarly, from the early Gorgan posing timidly before the camera to determining their self-representation in snapshots photographs of births, family gatherings, lazy afternoons that have been extracted out of their own albums and mobile phones into the sacred realm of the gallery space to Pernot’s fine art photography being re-appropriated by the Gorgan and serving as post-mortems on their family graves, these images reveal an infinity of uses, practices and dynamic relations between the subject and the photographer.

This sustained demystification of the photographic image, which both recovers its status as an extinct amulet and quotidian object bestows on the work an unforeseen authenticity. It is a level of authenticity achieved not out of fascination nor by means of attempting to build a bridge with the ethnographic ‘other’, but naturally, in an unhindered way. Here photography is actually about and for something.

As noted by both Clément Chéroux and Johanne Lindskog in essays from the accompanying publication by Xavier Barral, Les Gorgan project transgresses with wit the boundaries of the ethnographic, the cultural and the anthropologic. For those who wish to detect in the project folkloric clichés and ethnographic archetypes, gypsy matriarchy and palm reading, it is indeed all there. And yet crucially and suddenly the Gorgan turn from characters to people. Expanding idly on the surface of the image, their bodies are humanised under the weight of time and human destiny. At the same time, they are infused with an awareness of the confined territory they occupy between the lens and the world.

Beyond the personal, the familiar and various trappings of the photo community or art world, Les Gorgan resonates with history. While accessing the Camargue local archives as a historian for an exhibition in 1998, by chance he came across hundreds of police identification files of former Saliers gypsy camp inmates under the Vichy regime. He also discovered that Bietschika Gorgan, the patriarch of the family, was deported to Buchenwald in 1944. In this knowledge, the formidable face and side portraits of the children in Photo booths can inevitably be seen under a novel, dark perspective. They involuntarily awake memories of seclusion, deportation and extermination of these minorities during World War II. Likewise, they speak eloquently of the implementation of photography as an authority and means of control. In fact, they still do given the recent evictions of Roma migrants from France in 2009, turning the whole work into a cumulus of embedded history, memory and trauma.

Silence in Les Gorgan is suggestive. For the story remains untold and is crude and partial. The gaze is distance, and the ‘other’ a fabricated construct to accommodate it. Visually exuberant at first glance, Pernot’s narrative gradually reveals itself as a complex object of relations among subjects, gazes and modes of representation. By abolishing hierarchies between the artistic, the quotidian and the banal, and by dissolving the status of narration and voices, ‘it recreates’, in Pernot’s words, ‘the circumstances of each member of the family, and recounts the story that he and the Gorgans wrote together; face to face, then side by side’. As such, it daringly takes a stance to reconstruct the dialogical structure of history from the viewpoint of the ones who have not written it, recovering and ultimately surpassing the proper experience of photography. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist and Xavier Barral. © Mathieu Pernot

—

Natasha Christia is a writer, curator and educator based in Barcelona.