Matthew Connors

Fire in Cairo

Book review by Max Houghton

The end is where we start from. This oft-quoted line from T.S. Eliot’s Little Giddings was an expression of philosophical, spiritual and, perhaps, aesthetic renewal after the horrors of the two world wars. It is also a deliberate conceptual strategy in the making of Fire in Cairo by Matthew Connors, a book which reads back-to-front. When many of us encounter a photo-book, this is how we flip through it, anyway. It’s a curious but pervasive quirk. Books in Arabic are ‘read backwards’ or, more accurately, they are read in the reverse direction to books in, for example, Germanic or Romance scripts. It is important, however, to note that language itself doesn’t have a direction.

Among Connors’ achievements with this work is that he has harnessed the energy of fire and revolution and used it as a charge for his own creativity, with this vivid green, cloth-covered book. It opens, at the ‘back’, with a short story which oscillates between sexual intimacy, the history of torture and the impossibility of knowledge, only to end in silence. This is our territory. He lands the reader in Midan Simon Bolivar, Cairo, a location which, like its eponymous hero, symbolises the people’s struggle and the possibility for change and freedom. During the heady days of 2011, when nearby Tahrir Square was the epicentre of the uprising to oust Mubarak, a bandage was placed over the eye of the Bolivar statue, after police had employed tear gas. As Pablo Neruda writes of Bolivar, “I wake every hundred years when the people are awake.” The story closes with its narrator detained, while the “bureaucracy of retribution” is adjudicated. As a description of what follows the fever and ferment of revolution, this chilling phrase conjures tedium, injustice and quiet threat of violence still to come.

We turn the page to a different kind of not-knowing: a portrait in black and white of an older man, in what I will lazily call traditional Arab dress. I cannot say if there is further significance to his attire – it may be clerical. Like the narrator, I am reminded constantly of my lack of knowledge. An extensive series of paired portraits follow this single image and, with a couple of disruptions, we are still seeing in black and white. Connors took two images of each person, seconds apart, and the editing process led to this effective juxtaposition, in which we can perceive subtle changes in light or expression. One pairing is of two different men – police not protestors – and is the exception that proves the rule. With this series, Connors invites the reader to question the nature of a photographic portrait, shown here to be always in flux. His doublings create a kind of binocular vision, without the illusion of depth.

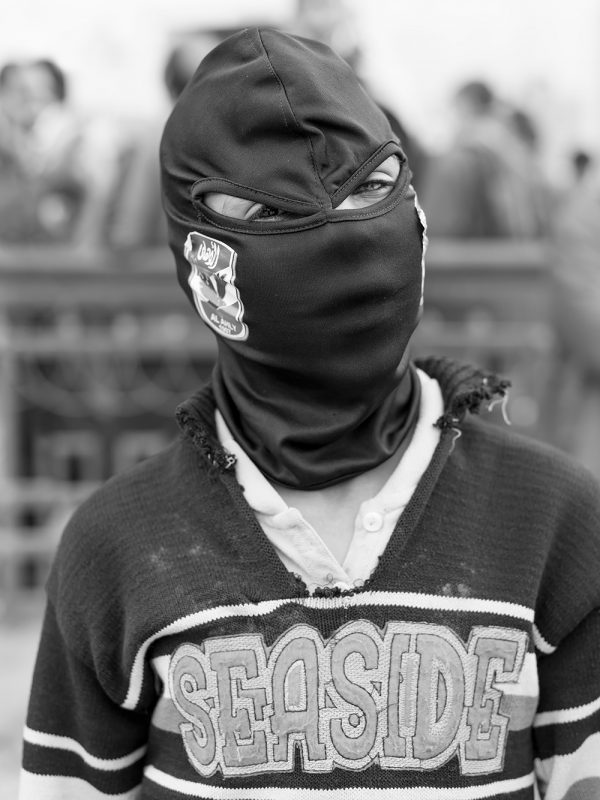

These portraits begin a sustained meditation on sight and sightlessness, and speech and silence that courses through the work. The right eye of the first young man pictured is occluded. A few pages on, another young man sports a plaster on the delicate tissue just below his eye. Another man wears a scarf, creeping up to obscure his sight. A veiled woman has only a narrow aperture through which to see, curtailing her peripheral vision, as do the hoods of sportswear worn by others. A masked man’s eyes are open to the elements, his mouth a covered orifice. Then, on subsequent pages, fire ablaze in orange. Fire that seems to hang like a mushroom cloud in the sky, though the flames flare from tyres burning on the ground.

Next, another pairing is of a boy with an oversized sweatband concealing most of his eyes, as well as his nose and mouth. This seems to be the last doubling, as overleaf a vivid image of bright green laser lines engulfs the reader’s vision. This is the image on which the work turns. Now: riot police and tear gas trails. Then one final portrait pair (for now); this time in a full skull mask with upturned eye-socket slits, rendering the face underneath bug-like. Metamorphosis can indeed be a reasonable response to oppression. Questions of freedom of speech; the right to say what has been seen (another impossible task); the right to remain silent, hover over these faces, wary, vulnerable, fearless, hidden, exposed, altered.

During the uprisings – and since – thousands of people used laser pointers as an act of protest, shining their light at military helicopters in an attempt to knock them off course. In Fire in Cairo, the images they created in the night sky becomes a leitmotif, the most important in the book. They are images of protest, a union of technology and direct action, even, if we take the etymological light-writing definition, a new and potent photography.

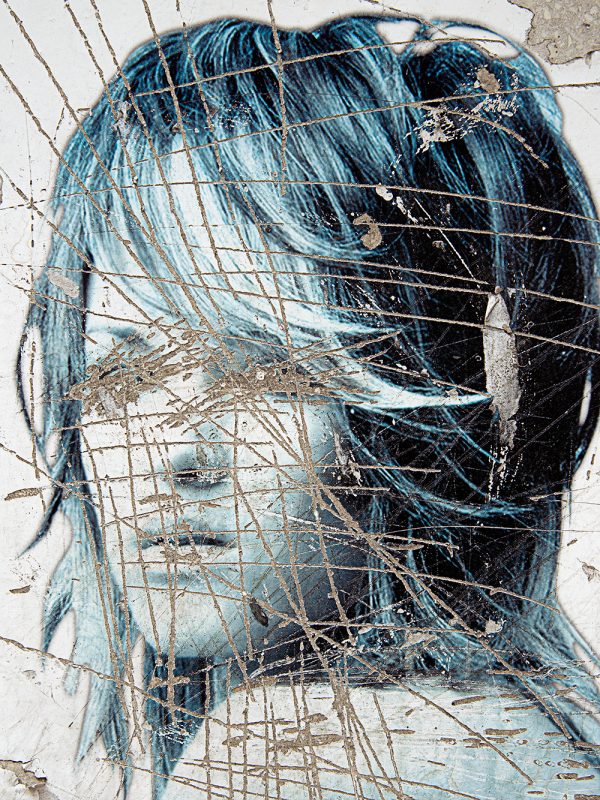

Other images depict a city heading towards ruin — torn down posters, remnants of things destroyed by fire, shadows through trees, a young man clutching something that might detonate if thrown, a man bent double in apparent despair, military helicopters, birds in flight or fright. On seeing a found photograph of a bride, I am struck by the thought that it is in fact a lost photograph, unsutured from its family album. A graphic poster of a teenage girl has her face, especially her eyes, repeatedly and violently struck out. As the book draws to a close, a sinister portrait pairing reminds us of our compulsion to repeat. The figure is fully covered by a black garment, with a mirrored mask over the face, reflecting back a view of the contested landscape of the street. The revolution through masked and unseeing eyes. It is a mannequin, but such distinctions between real and unreal no longer make sense. The view thereafter is upwards. A sky redesigned by smoke and fire. Is that encroaching blood? Gathering darkness? New constellations have been created with green light, though we cannot be sure how long their luminescence will endure. They have, like pinned butterflies, been captured here. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist and Self Publish, Be Happy. © Matthew Connors

—

Max Houghton writes about photographs for the international arts press, including FOAM, Photoworks and The Telegraph. She edited the photography biannual 8 Magazine for six years and is also Senior Lecturer in Photography at London College of Communication – University of the Arts, London.