Max Ferguson

Whistling for Owls

Book review by Anneka French

Max Ferguson’s debut publication, a contemplative study on paper, nature and the passage of time, transcends the physical limitations of its form to connect readers to their senses and memories, writes Anneka French.

Glassine, a smooth, distinctively rustling, semi-translucent paper, is a material I remember from childhood. My father, a teacher with a weekend philatelic side-hustle, displayed stamps in albums on pages separated by glassine leaves, stamps tweezed into tiny glassine envelopes when he made a sale. I remember scrambling on my knees under tables collecting sequins shed from the hall’s ballroom competitions the night before. Multiple memories surface as I open Whistling for Owls, the debut photobook by Max Ferguson and the first from his Oval Press imprint. Memory and the passing of time are two of the subjects at the heart of the publication, which contains within it a hand-folded triangle of glassine bound into its spine. The triangle is sandwiched between a photograph of three dead butterflies with their own glassine slips on the left-hand page and two transparent glass vases of dried flowers on the right, fitting because glassine is also used in entomological field specimen storage. Here, then, you might insert your own moth or marvel.

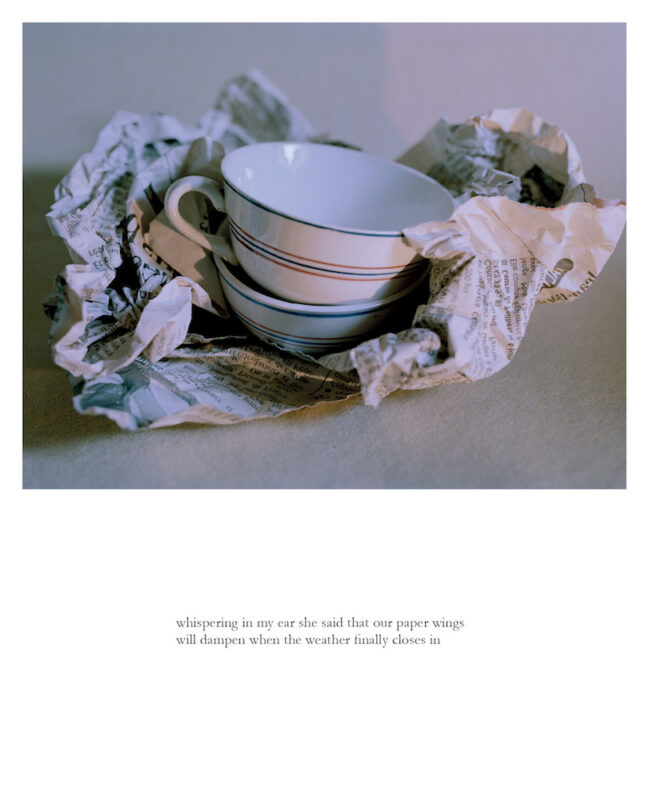

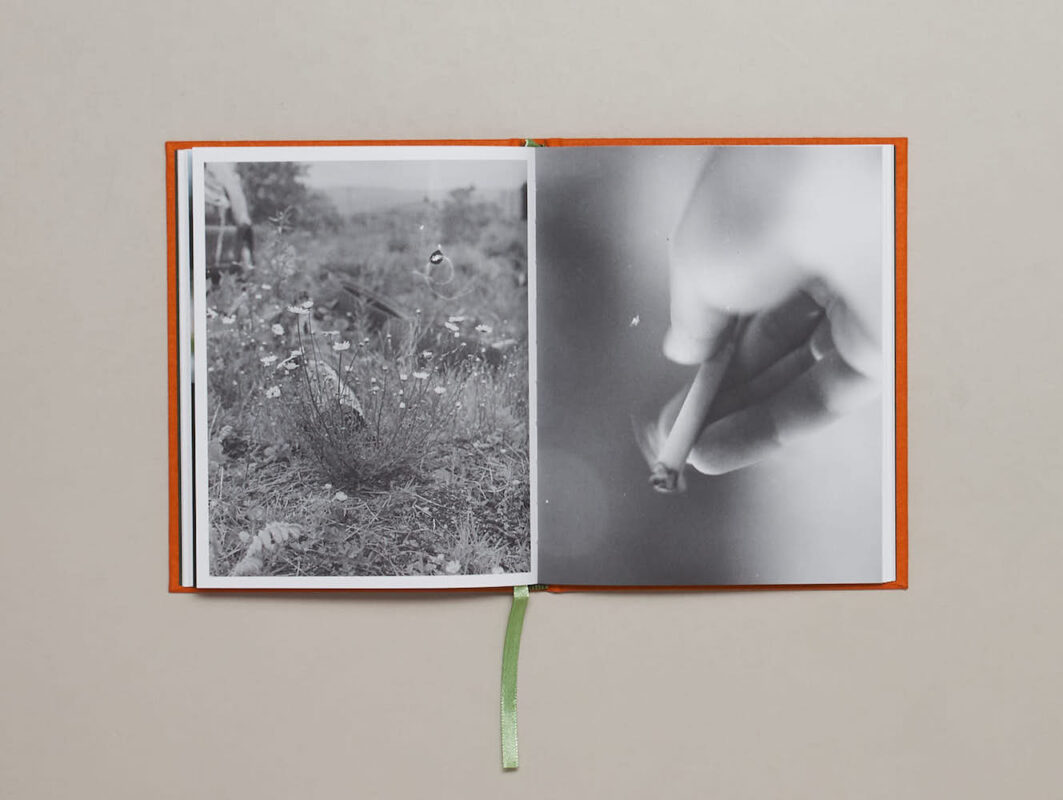

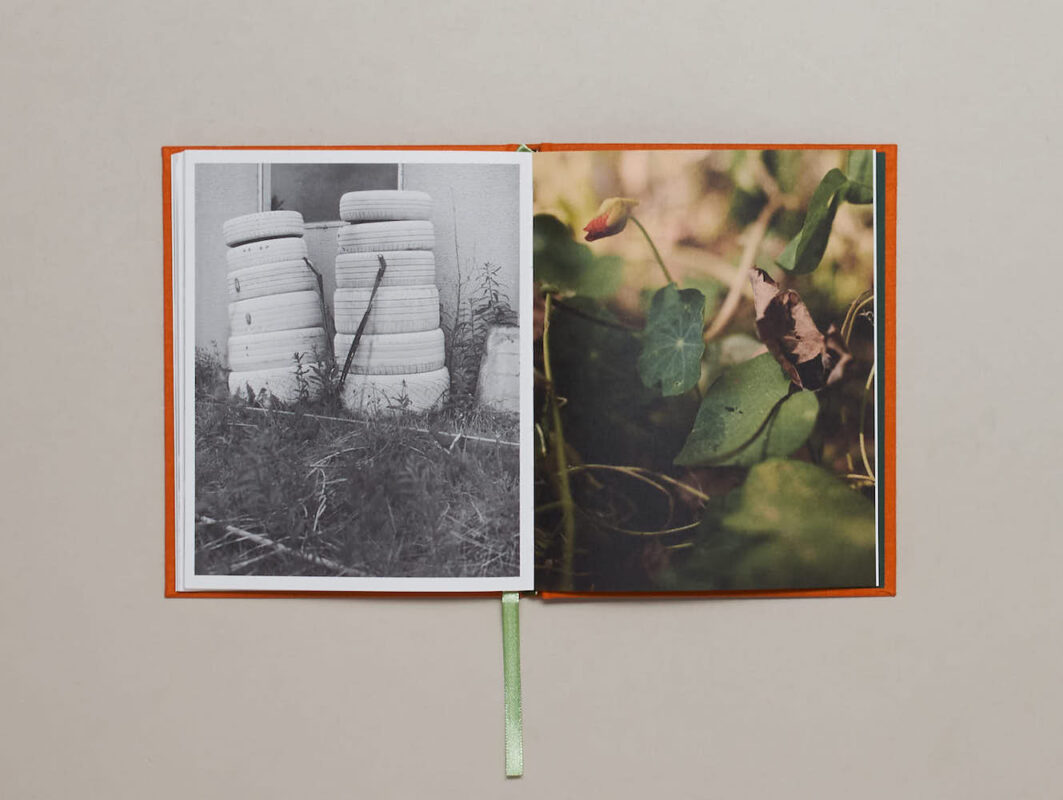

Whistling for Owls is filled with small, daily records, although to describe them as simply quotidian would be reductive. Photographs of objects ranging from the domestic to the industrial feature in a mixture of colour and black-and-white. They are undeniably romantic and many objects are gently decaying or have stalled. We find photographs of daisies, foxgloves and tangled weeds; concrete slabs and chunks of stone; a cutlery drawer; rusty oil drums; a broken intercom and an assortment of portraits. There are pairs of objects – two towers of stacked tyres repeated twice in subtle variation; two tomatoes balanced on a checked cloth; two teacups cradled in newspaper as if they have just been unpacked – all rendered symbolic, even if their precise meaning is unclear. Pairings are noteworthy since Ferguson himself places emphasis on the book being formed from two parts. He describes it as “image and text; France and London; memoir and fiction; truth and lies,” telling us everything and nothing. Indeed, much of the book’s impact is derived from its ambiguity, as well as its striking beauty.

Some of the strongest and most curious photographs are the portraits and other depictions of the human body that pepper the book, elevating the quieter still-life studies and cutting through some of the romanticism. These include an older man with grey hair caught out of focus in a hunched, turning movement; a sculptural-looking hand holding a cigarette; the lit underside of two inviting thighs; feet in plastic sliders. Again, we find photographs that echo one another in the close-up of a woman turned towards the right with eyes closed to the sun, followed a few pages later by another turned towards the left reclining on a sun lounger with her eyes closed too. Nearing the end of the book are more doubled images of bodies in repose, this time a woman in striped shirt with soft curls and bare legs preceded by a lumpy body in baggy clothing and boots with a dismembered hand – probably a scarecrow – though clever cropping initially disguises this. There is bliss, intimacy, violence.

A loose, non-linear narrative unfolds through eighty-four pages, revealing photographs in ones, twos and threes which are at times accompanied by fragments of text. Ferguson controls the viewing experience by giving images space to breathe, slowing the reading of the work and enabling connections to be traced through its entirety. Photographs are printed full bleed or on differing parts of the page and the effect is as though the images within Whistling for Owls flicker in and out as beats with a sinuous rhythm. In one photograph, worn render on a wall exposes stones like teeth in a grimace; in others we find a verdant green cricket and a discarded apple core. We are presented with the flavour of fresh, plump tomatoes, placed pleasingly amid pages of hot, dry grass, stone, plastic and skin. The photographs operate on frequencies that overlap with tangible experiences of small pleasures while attention is drawn to the heavy weight of emotion in Ferguson’s pages.

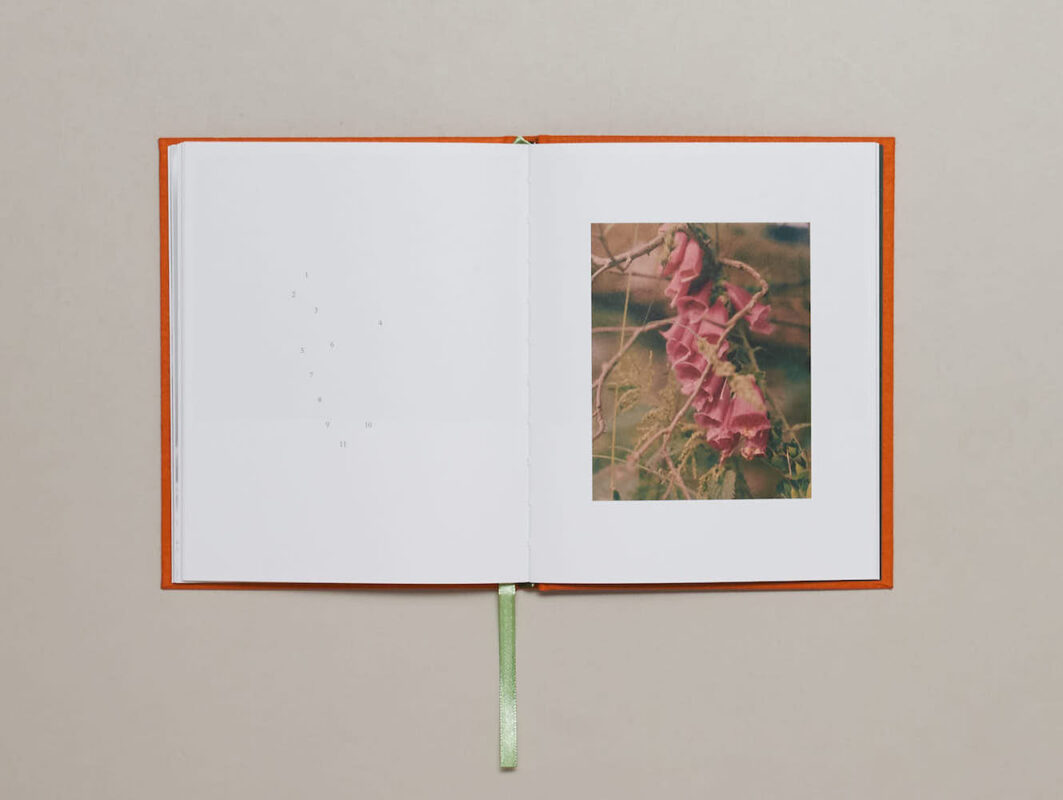

The text within Whistling for Owls is largely similar to the content of the photographs: paper, the weather, the passage of time. There are texts that introduce characters into the mix by way of the printer, the birdwatcher and the poet, giving rise to speculation about which portrait we might attach each of these labels too. The text is, in many instances, abstract and seemingly personal, with one page showing a sequence of apparently randomly spaced numbers, though pages are also given over to occasional descriptive lists. Narrative fragments are brief and yet full of possibility, as is the book’s title. The text is overtly poetic, dealing with feelings of desire and yearning. ‘The proximity of what you love makes you so lonely,’ reads the last line of a short passage set on the deck of a ferry. The feeling of loneliness connects with an earlier section describing coping with long months through therapeutic, repeated morning rituals. While most likely symptomatic of enforced periods of lockdown during the past two years, this sentiment remains implicit.

Whistling for Owls is bound in bright orange cloth with dark green endpapers and a lime green ribbon. These choices serve to highlight Ferguson’s precise and minimal use of colour within the photographs, particularly in leaves, grasses, berries and warm, glowing light. A reader can follow their own path here, from the front to the back of the book or leaf through pages more casually, and all these journeys into the book are fruitful. Images and lines of text touch one another physically and metaphorically, lying stacked on top of each other when the book’s pages are closed or pulling apart as the book is opened. The photographs of Whistling for Owls are lifted by the insertion of the audible and textural, glassine fragment folded into three-dimensions, but the photographs are evocative and emotive in and of themselves. In the end, what is significant is the way that Ferguson offers images that frequently move beyond their own physical limitations as flat images by extending out to our senses and our memories. ♦

All images courtesy the artist and Oval Press © Max Ferguson

—

Anneka French is a writer, artist and independent curator currently working with Coventry Biennial. She regularly contributes to Art Quarterly and Photomonitor, and has had writing and editorial commissions for Turner Prize 2021; Fire Station Artists’ Studios; TACO!; Photoworks+ and Grain Projects. She previously worked as Co-ordinator and then Director at New Art West Midlands, as Editorial Manager of this is tomorrow and has worked at Tate Modern, London; Ikon Gallery, Birmingham; The New Art Gallery Walsall, and Wolverhampton Art Gallery.