Peter J. Cohen

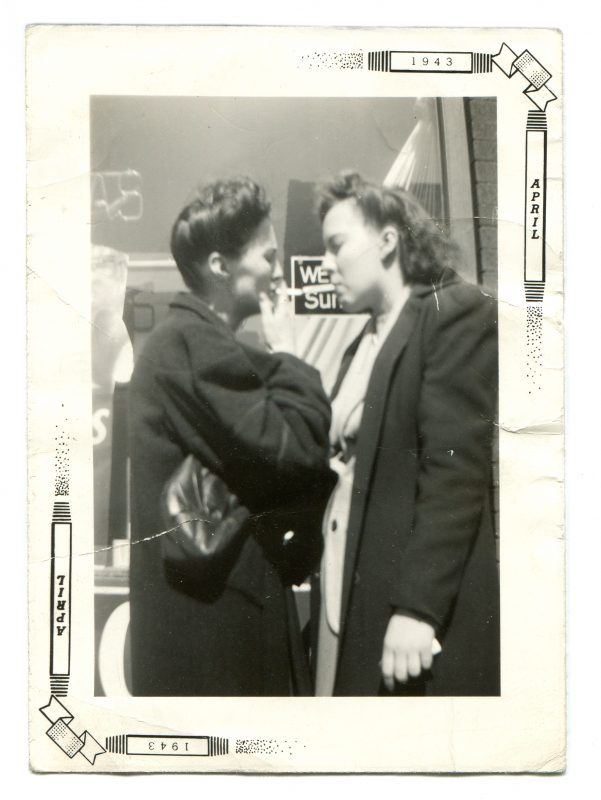

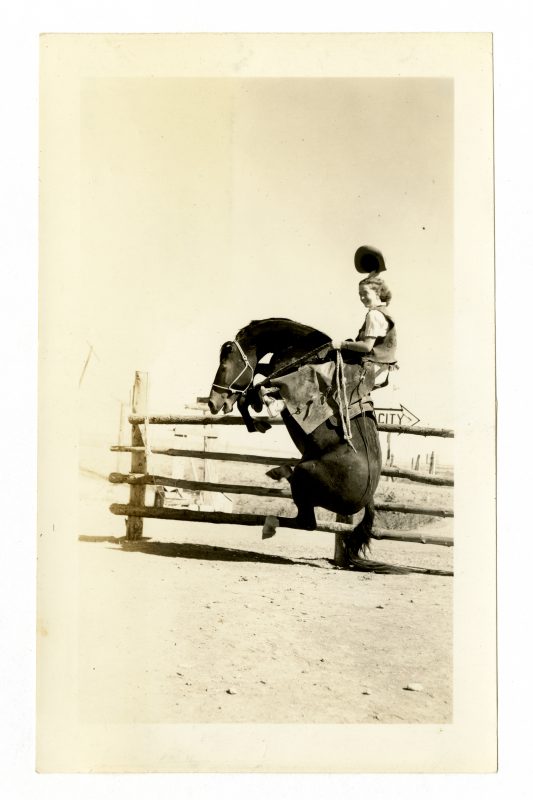

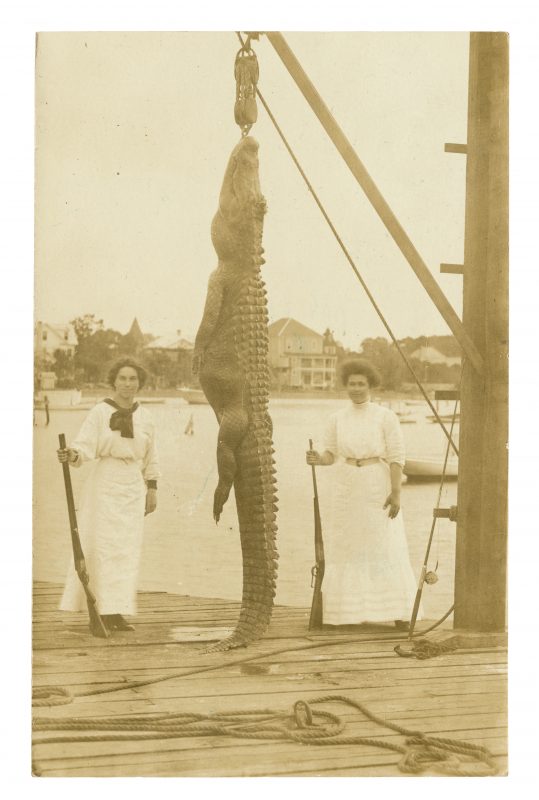

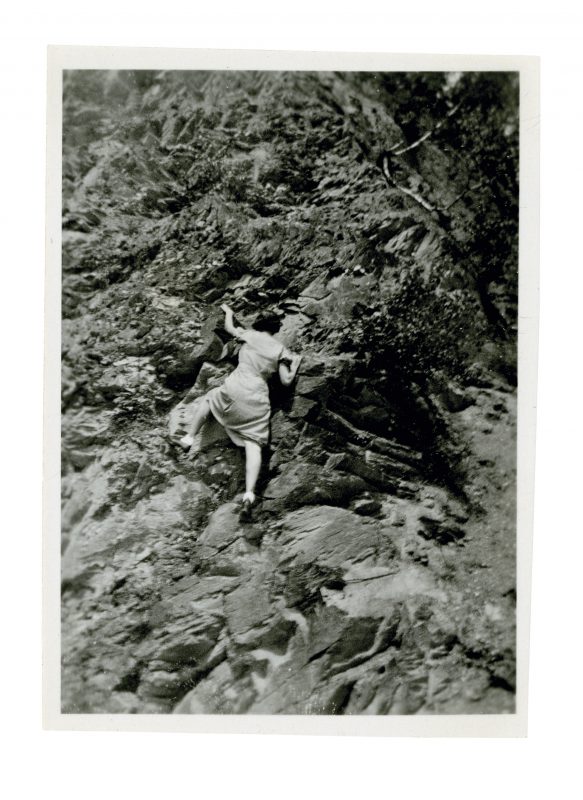

Snapshots of Dangerous Women

Book review by Susan Bright

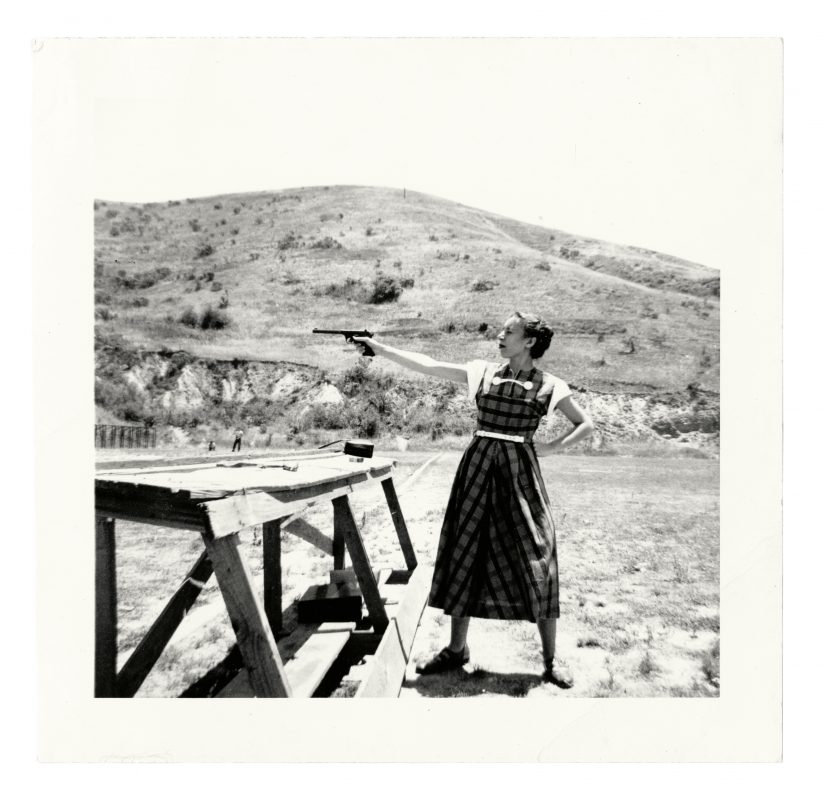

I am writing this review in the wake of yet another public shooting in America. Flicking through Snapshots of Dangerous Women I am struck by the amount of photographs of women with guns. This, of course, is a symbol of a particular sexual fantasy, but these photographs are different from the ‘women with gun’ trope that may spring to mind. These are not objectified women in unlikely scenarios posing in order to validate fantasies – they are candid snapshots. They don’t feel dangerous in the way guns really are. Instead, the women here feel rather fierce and altogether comfortable with their weapons. Often, the pictures of them come across as elicit.

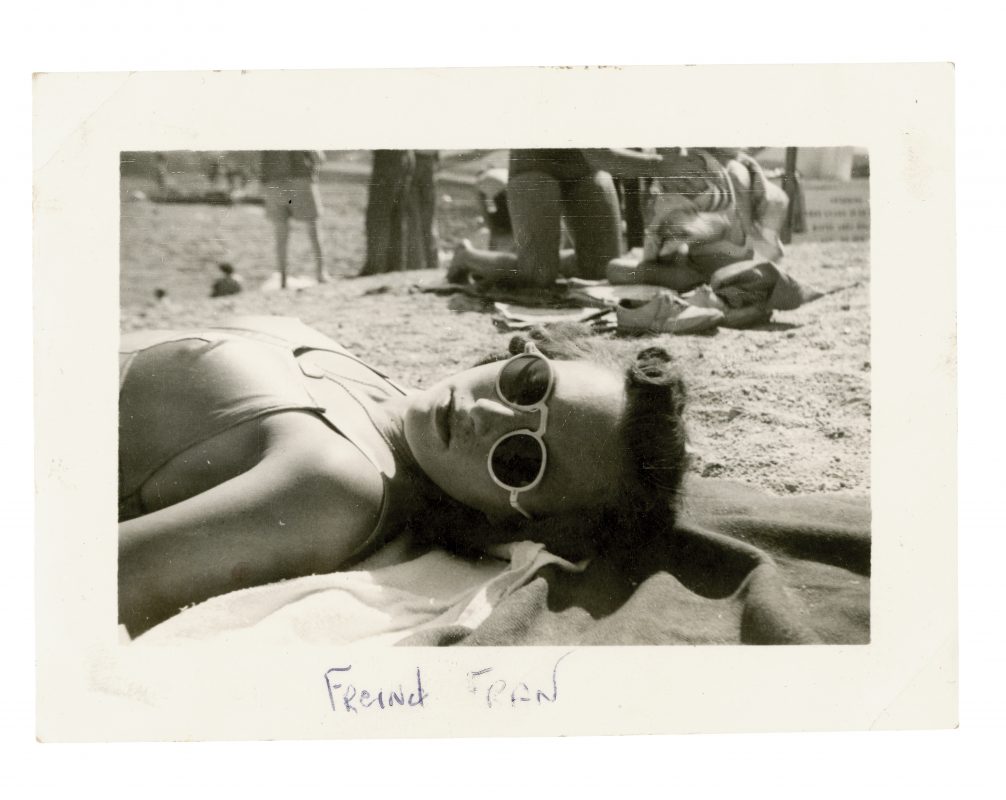

So the title Snapshots of Dangerous Women rankles. These women are not dangerous (and if they are then I would ask dangerous to whom? The answer, of course, is obvious – I don’t have to spell it out). Instead, these women are happy, free, strong, often goofy, and rather glorious. They are young Americans and the photographs of them range from the early twentieth century to the 1950s. They are women enjoying themselves heartily: drinking, smoking, dancing, driving fast cars, fighting, fishing or just posing with a free abandonment and glorious self-confidence. Or, to put it another way, it shows women behaving just like men.

I read that the collector, Peter J. Cohen – from whose vast collection of vernacular photographs these snapshots are sourced – wanted the title to be deliberately provocative. But it doesn’t feel that way; it feels more like a marketing ploy for sales. And this is a great shame as it is really a terrific selection of snapshots that say a great deal about the social and familial conditions of the time they were taken.

The scholar Geoffrey Batchen claims that “snapshots show the struggles of particular individuals to conform to the social expectations, and visual tropes, of their sex and class […] everyone simultaneously wants to look like themselves and like everyone else […] Before all else, snapshots are odes to conformist individualism”¹. Not so for these women. They have no desire to look like anyone but themselves and do the complete opposite of what is expected of their sex and class.

Batchen’s writing on snapshots, from only seven years ago, shows how much the culture of the photography has changed in this time. He states that snapshots have relatively little market or museum value. This has has shifted dramatically recently as museums reconsider their relationship with vernacular photography, both in terms of acquisitions and display. Auctions now regularly include more vernacular photography of the early-to-middle twentieth century, and flea market prices for albums and collections can be somewhat astonishing. The way we express ourselves in our own life narratives online has become an increasingly prolific part of photographic culture, too, and, as result, vintage snapshots have become all the more valuable. The very fact that books like this are made goes someway to illustrating this.

The book itself is perfect: it’s not too big. Snapshots need to be kept to near their original size in publications. To blow them up too big makes a mockery of their purpose and charm. To make them too small turns them into treasured jewels – which, by their very nature, they are not. The uncut pages take any preciousness away and the mix of full bleed and reproductions of the full photograph means the book has a good fast rhythm that doesn’t feel at all repetitive. The mix between the reproduction of image and object is beautifully balanced.

The introduction is formed by a series of quotes and facts about various women and events covering the period under examination. They are structured in short pithy sentences. This is just right for the book. Mia Fineman (Curator of Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) has curated and written about vernacular photography and the range of quotes she has sourced shows she has spent time with the collection, and really understands the social conditions for women of the times, whilst simultaneously rooting for their more unconventional lifestyles.

The most beguiling images are those of groups of women together or two friends. My favourite is what looks like a sleepover. It shows four women lounging drunkenly together. They are bunched up to get in the frame at what feels like the end of the evening. They are all smoking; one holds a near-empty bottle up in a drunken yet triumphant gesture. The woman on the far left is dressed in dashing striped pyjamas and you have to look twice to see that she is a woman as her short cropped hair is at odds with her beautifully manicured nails. The room is a mess and it’s only too easy to imagine the awful hangovers that will haunt them all the following day. I imagine them smooching around together eating vast amounts, empty-headed, laughing, and napping whenever they get a chance.

But although the collection is joyous, it also left me feeling a little melancholic. How awful that women had to hide this side of their character away only to be revealed in the privacy of their own environment and to somebody they trusted behind the camera. In the photographic culture today, where vernacular photography can be understood in terms of the selfie and other online versions of self, the judgement of how women should and should not act in front of the camera continues, as evidenced by the vast amount of writing on the supposed narcissism and shallowness of (mainly younger) women. Wouldn’t photographic representations be all the more richer if women felt they could behave how they damn well pleased and not be shamed, judged, fetishised, or, indeed, labelled as ‘dangerous’ for having done so? ♦

¹Batchen, G. (2008). “Snapshots.” Photographies 1(2): 121-142.

All images courtesy of Rizzoli. © Peter J. Cohen

—

Susan Bright is a curator and writer. Her published books include Art Photography Now (2005), Face of Fashion (2007), How We Are: Photographing Britain (2007: co-authored with Val Williams) Auto Focus (2010) and Home Truths: Photography and Motherhood (2013). The exhibition How We Are: Photographing Britain was the first major photographic exhibition of British photography at Tate. The exhibition of Home Truths (Photographers’ Gallery and the Foundling Museum and traveling to MoCP, Chicago and Belfast Exposed) was named one of the top exhibitions of 2013/2014 by The Guardian and The Chicago Tribune. Bright was visiting scholar at the Art Institute Boston in 2014. She currently lives in Paris and is completing her PhD in Curatorial Studies at Goldsmiths College, University of London.