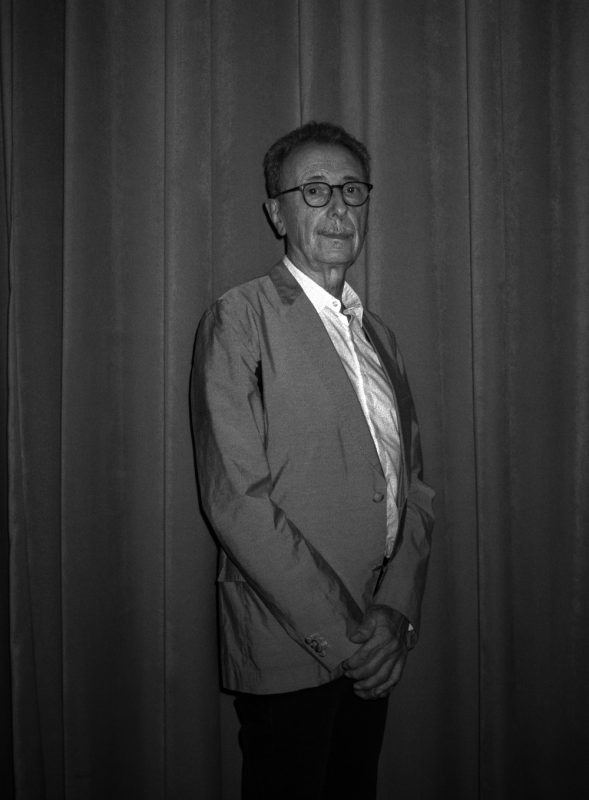

Victor Burgin

Author of The Camera: Essence and Apparatus

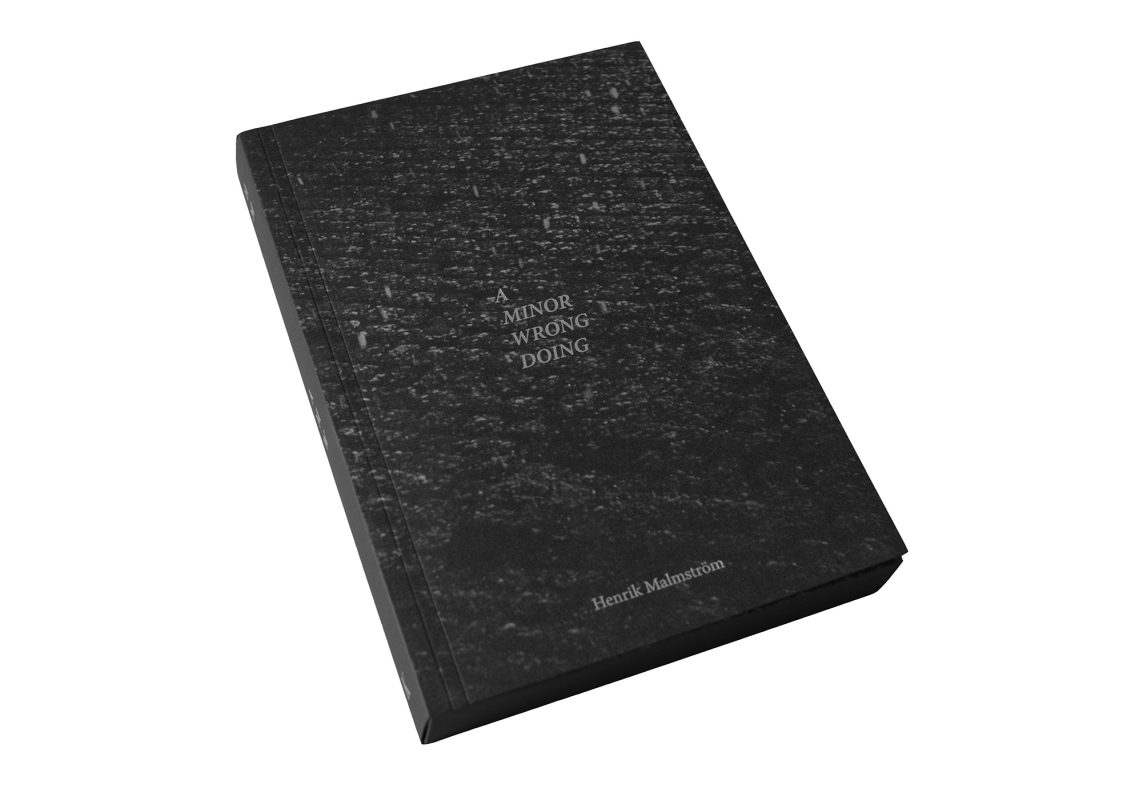

Published by MACK

Continuing our Interviews series, photographer, writer and Director of Art Foto Mode, Michael Grieve speaks with Victor Burgin, one of the most influential artists and writers working today, having first rose to prominence as a conceptual artist at the end of the 1960s. His theoretical essays on both the still and moving image encompass semiotics, psychoanalysis, and feminism and were recently brought together for the first time as a collection in The Camera: Essence and Apparatus, published by MACK in 2018.

Here Burgin discusses how over the past five decades his work has never stopped being political. What has changed, he says, is his understanding of the forms of politics specific to art. He also reflects on the way the conditions of spectatorship of moving image works made for the gallery are closer to those traditionally associated with painting than to those associated with cinema. And while he once argued that the specificity of photography lay not in its medium but in its apparatus – the still camera – and most especially in the speed of this apparatus in registering the fleeting appearances of the world, today the photographic apparatus is no longer specific to photography, the specificity of photography now is in its apparatus, whether that be discourses that take photography as their object – technical, historical, sociological, philosophical, curatorial, critical, journalistic and so on; institutions such as certain museums, societies, photography departments in universities, prizes and other instruments of legitimisation; or forms that include the various types of structures within which photographs are presented, such as billboards and plasma screens, art museums and galleries, magazines and newspapers, and the Internet.

Michael Grieve: Your interest in photography began in the late 1960s when you began to think critically about commonly held assumptions ingrained in the art world. Perhaps the seed of your thinking was sown as a student at the Royal College of Art, London. Thus you began to work conceptually fusing text, photography and film together. At this early point in your ‘artistic’ process how did you arrive at the conclusion to work in this way, and were you clear of your convictions as to the trajectory you wanted to move towards?

Victor Burgin: In the introduction to my essay collection The Camera:Essence and Apparatus (2018) I write: “I came to ‘photography’ from a background in ‘art’ at a time, the late 1960s, when the art world considered the expression ‘art photography’ to be an oxymoron. What interested me about photography was the place it occupied in everyday life. In newspapers, magazines, advertising, family photographs, and so on, it played – as it still plays – a fundamental role in the formation of the ideas, beliefs and values according to which people live. To use photography in my works for art galleries and museums therefore allowed me to bring my visual art practice into dialogue with a significant aspect of the sociopolitical process. It moreover required that my critical thinking about my practice take account of a world beyond the ‘art world’.” A detail to add to this was my growing disenchantment with the hermeticism of Conceptual Art. My decision to work with photography and text represented my turning away from concerns inherited from ‘art’ and towards everyday life and its languages, which are invariably composed of image/text relations. Of course such an orientation, unusual at the time, has since become unexceptional.

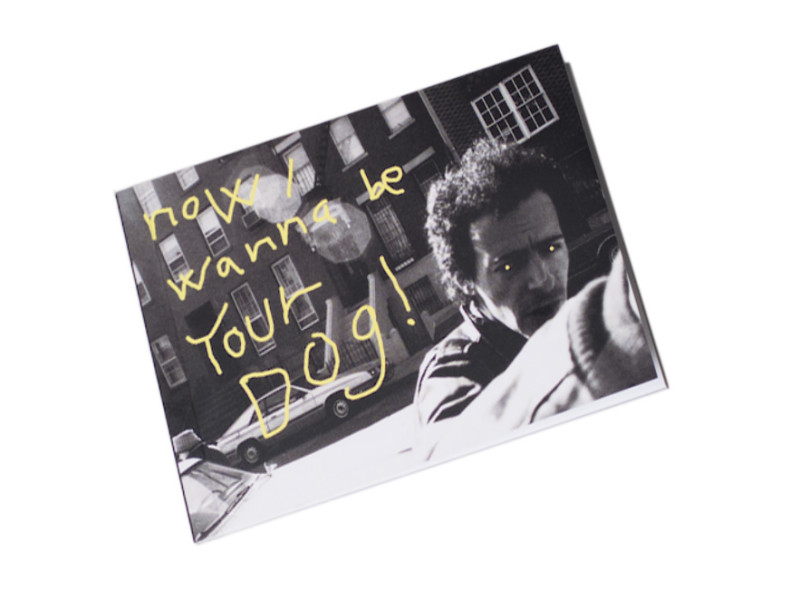

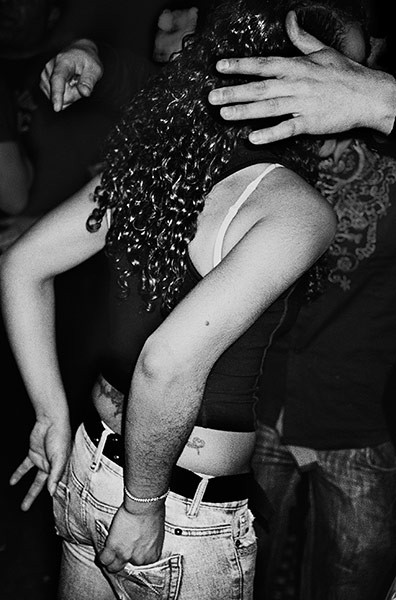

MG: The first work I encountered of yours was in my hometown of Newcastle upon Tyne. In 1976 you produced a singular work called Possession, appropriating the style of advertising, with the text reading, “What does possession mean to you?” and, “7% of our population own 84% of our wealth”. Juxtaposed in between is a photograph of an attractive man and woman in an intimate embrace, the man’s face partially obscured by the woman’s profile as she kisses him on the cheek and holds the back of his head. 500 reproductions of this image were printed and specifically situated on the streets of Newcastle upon Tyne. This is a rhetorical work yet fused with multiple meanings oscillating between image and text. I want to use this particular work as a prime and early example of your conceptual approach. Can you explain your thinking at this time and how your practice today follows the red line of image/text relations?

VB: What comes to mind is a review of two shows of my work held simultaneously in New York in 2016. One show was of UK76, the other was of two recent digital projection works. The critic approves of the “agonistic relationship to the gallery” in my earlier work, and especially in works like What does possession mean to you? On the other hand he finds that my recent works, unlike my work of 40 years ago, “give off the strange air of an academic exercise”. He would more accurately have claimed the contrary. Works such as UK76 and What does possession mean to you? were the closest I have ever come to making art as an “academic exercise”, a putting into practice of theory. Both works are intimately related to my essay Photographic Practice and Art Theory which was published in 1975 at the time I was putting together those works. This essay, in turn, was derived from my lecture notes for the class I was teaching in the Film and Photography department of the Polytechnic of Central London. The class was devoted to the application of linguistic theory in the analysis of text-image relations in photography in general, and advertising and documentary in particular. The reviewer assumes it to be unquestionably self-evident that the “academic exercise” is a bad thing. To the contrary, it is often the only way to break the iron grip of established habits of thought, and to open the way to non-consensual forms of representation. I’ve become accustomed to being told that my work “used to be political”. To which I reply that my work has never stopped being political; what has changed is my understanding of the forms of politics specific to art, rather than, for example, to campaigning journalism or agit-prop. Moreover the political environment has greatly changed. My forays into the street in the 1970s made sense in the political context of the UK at that time – with a genuinely socialist Labour Party and significant party and extra-party pressure groups further to the left. To make work today as if I were still in that context would be ridiculous. I summed up the shift in my thinking in a chiasmus I coined back in the early 1980s, when I said that for me the issue was no longer one of the representation of politics but of the politics of representation.

MG: During the early 1990s I was a student at the Polytechnic of Central London [now the University of Westminster], where you were a lecturer between 1973-88. Even in absence, your educational legacy was very much present. Thinking Photography (1982), a book of seminal texts which you edited was at the top of the curricular reading list. I am curious to know how much input you had in changing the content and structure of the course towards a way of rethinking photography and its place in culture and society; utilising and integrating theories such as psychoanalysis, semiotics, post-structuralism and feminism, theories that had previously been regarded as mutually exclusive to critically understanding visual representation. And in which ways was your previous lecturing experience at Trent Polytechnic precursory to PCL?

VB: I was hired at what was then the Polytechnic of Central London in 1973 precisely because PCL was in the process of applying for BA (Hons) degree accreditation, which meant it had to provide academic content in what had previously been a vocational course. Such content at PCL up to 1973 had been confined to classes in optics and chemistry. I had begun rethinking my intellectual assumptions as a student in the 1950s, while doing summer work as a labourer in a Sheffield steelworks. One of the young men working alongside me was studying philosophy at Oxford. When he heard I was attending the local art school he told me about A. J. Ayer’s book Language, Truth, and Logic (1936). In this book Ayer argues that a sentence can be meaningful only if it is ‘analytic’ (tautological, like mathematics), or empirically verifiable. If a sentence is neither, it is literally nonsensical. Ayer applies this ‘verification principle’ to ethical, theological and aesthetic propositions. All fail the test and are condemned as meaningless. This chance introduction to Ayer’s book came at the right moment for me. I was having difficulty making much sense of what painting tutors and art critics were saying. It came as a relief to learn they were talking nonsense. This was the beginning of my search for an appropriate critical language for thinking through my art practice. When I subsequently went to the Royal College of Art painting school I was lucky enough to take classes with Iris Murdoch. She introduced me to British empiricism, Hume in particular. I had already read Sartre’s novels at art school in Sheffield, so I read her work on Sartre ‘on the side’ and became interested in phenomenology, an interest I subsequently pursued at Yale, where I read Husserl. The next major moment in my intellectual history came sometime after I returned to the UK. It would have been somewhere around 1971. I was in my first teaching job, at Nottingham School of Art, and had become friendly with a colleague with a background in anthropology. I believe we had bonded over Georges Charbonnier’s Conversations with Claude Levi-Strauss (1961), which I had read in English translation in this small Jonathan Cape edition. I would guess it was this that led my colleague to recommend that I read Elements of Semiology (1964), which had also been translated for Cape. It was a ‘Saul on the road to Damascus’ moment in my intellectual history. After that first reading – of course it’s a book I continued to re-read – I went looking for other books by Barthes and found only Writing Degree Zero (1953), in the same Cape series. There were no other English translations of Barthes available at that time. So I went to Paris and came back with a bag full of assorted texts, not only by Barthes but also by the writers he draws on in Elements. I bought myself a large French-English dictionary and sat down to work my way through them. An irony lost on me at the time was that S/Z had just appeared in France, signalling Barthes’ post-structuralist turn. Barthes later spoke of the way his investment in intellectual projects was a desiring one; they would endure for whatever periods of time they endured, like amorous investments, and then be overtaken by other passions. The affair with linguistic theory that gave birth to Elements, however, was arguably the longest and most intense. My encounter with Ayer, and with logical positivism in general, was almost as important to me as my encounter with Barthes some fifteen years later. One can hardly think of two more different thinkers, but they nevertheless performed complementary functions for me. Ayer allowed me to clear the ground of the kind of impressionistic and opinionated writing that was rife in so-called ‘art criticism’. Barthes allowed me to construct an alternative critical apparatus once that ground was cleared. At that time, in the 1970s, I didn’t know anyone else who was reading Barthes. The conceptualists I tended to be associated with then, mainly the Art Language group, trod the British ‘natural language’ philosophy line of hostility to what they called the ‘French disease’. The people who were reading Barthes were the film theorists around Screen magazine. I later became friendly with some of them, mainly with Peter Wollen and Laura Mulvey, but in the early 1970s I was pretty much intellectually isolated.

MG: Moving forward in time to Paris Photo 2019, when you were in conversation with David Campany and presented the project A Place to Read/Bir okuma yeri, a work made in Istanbul as an artist in residence in 2010. You constructed a digital text-image projection that was looped every 10 minutes of the Taslik Kahve coffee house; a building that actually no longer exists, loss being a consistent theme in your oeuvre. I was immediately struck how the digital reconstruction of the coffee house is viewed and surveyed from an aerial, all seeing perspective, as if from a drone. Can you explain this work, particularly in terms of time and narrative, and also expand on the meaning behind this panoptical point of view?

VB: For many years prior to 2010 most of my work had originated in invitations to respond to a city, or a building. When I was invited to Istanbul, in the context of Istanbul 2010: Cultural Capital of Europe, I found that the building I had chosen to work with could no longer be photographed. The Taşlik coffee house and garden, constructed between 1947-48, had been dismantled in 1988 to make way for a large luxury hotel. The architect of the coffee house, Sedad Hakki Eldem, had designed a modestly elegant building, on a splendid site overlooking the Bosphorus, which synthesised a seventeenth century Ottoman architectural vocabulary with that of twentieth century modernism. I chose this building as a basis for my work for two reasons: first, it succinctly articulated the Atatürk Republican ideal of the modern and democratic expression of a historically rooted Turkish national identity; secondly, the destruction of Istanbul’s heritage of fine public architecture in the interests of private profit seemed to me to be an urgent political issue. (In May 2013 a no less brutal ‘development’ plan for Gezi Park, by Taksim Square, sparked massive anti-government protests.) When the Swissôtel was built in 1988 the Taşlik coffee house was dismantled and part of it re-erected in a different position to be used as an orientalist tourist restaurant. The former garden was turned into a car park and where there was once a view of the Bosphorus there is now the view of a rooftop tennis court, replete with advertisements for mobile phones. Rather than give up the idea of working with the building I decided to abandon the physical camera in favour of the virtual. My project became one of reconstructing the coffee house in the virtual space of a computer model to disinter the utopian imaginary of the Taşlik Khave as it was at the time it was built. As befits a project of excavation the completed work was shown in the Istanbul Archeological Museum. Strictly speaking, I had already used a virtual camera in some prior works, where I describe a space by means of a panoramic movement created by stitching together a number of still photographs and animating them in software. This resulted in an incorporeal vision, in at least two senses. A real person, operating an actual movie camera, can never make a perfectly regular panoramic movement, whereas the movement of the virtual camera can be perfectly constant. More fundamentally, the image produced by the real camera will contain parallax effects – for example, an object in the background may appear first to the left of a foreground object and then move to the right as the camera continues its movement – but this can’t be allowed to happen when stitching stills together; otherwise a seamless match of images will be impossible. The only way to avoid parallax is to have the ‘nodal point’ of the lens, the virtual point where the light rays intersect, exactly coincide with the point around which the camera rotates: a mathematical point of zero dimensions which cannot be an embodied human point-of-view. In works prior to A Place to Read I had made such panoramas in order to describe a space as simply as possible, making only the most minimal aesthetic decisions. For example, another technical requirement when stitching images into a panorama is that the camera should remain perfectly horizontal. My ‘artistic’ intervention in the shot was limited to choosing the position of the camera and its height from the ground. The three moving image sequences that are interspersed with the intertitles in A Place to Read are similarly intended to describe the situation as simply as possible – to answer the question, “What is the least I need to show the viewer in order for them to understand what this place is?” I think of the sequences as equivalent to the three familiar front/top/side orthographic views that accompany the perspectival view in architectural drawings and 3D modelling programmes. In A Place to Read you first circle the coffee house from a high viewpoint, so you understand the form of the building and its relation to the garden and the water; you next descend to ground level and advance towards the coffee house down the path through the garden; and in the final sequence you have entered the building and the camera gives a static shot of the light moving across the interior. Your ‘drone’ association, incidentally, would not have been made in 2010 as drones had not yet hit the consumer market. In fact one of the other artists invited to make work for Istanbul 2010 got the organisers to spend a fortune shooting helicopter video footage of the city of a kind that today is routinely knocked off cheaply with a camera-equipped drone.

MG: At the talk you mentioned how images can now be made from cameras projecting light, scanning the surface of objects, as with Google mapping of the city, in order to render a 3D photographic image. This is opposed to light entering the camera. In scanning the surface of things and producing an illusion of depth, the camera apparatus is no longer letting reflected light in. This technological shift has profound consequences to our phenomenological and psychological perception, between our interior and exterior registering of reality. In your opinion what is happening here, how are we to understand this?

VB: We should understand it as a radical mutation in the history of the camera that nevertheless remains firmly attached to this history – precisely as a mutation, not a break. In the nineteenth century, photography replaced perspective drawing as the principle mode of pictorial representation of reality. Photography was consistent with the fundamental impulse of the Industrial Revolution: the delegation of previously time-consuming and skilled manual tasks to the automatic operation of machines. Where photography represents a shift from manual to mechanical execution, computer imaging affects a shift from mechanical to electronic execution. Manual perspective drawing with optical aids gives way to the mechanical operation of a machine, which then cedes place to electronic computation. The computer modelling programmes I use today still render space in terms of a representational system that originated in Italy around 1420, when Filippo Brunelleschi applied principals of optics and geometry to painting. To consider the camera in terms of the history of perspective therefore suggests a periodisation in which we may speak of pre-modern, industrial and digital photography. The shift across this history is both quantitative and qualitative – an increased amount of information is deployed in the interests of a higher degree of mimetic realism. However, where photography represents an aspect of the object in front of the camera, the computer may simulate the object in its entirety. This adds a particularly significant dimension to my periodisation of photography in terms of the history of perspective – a subversion of the imperialism of the single point-of-view. When we pass from capturing an object in a 2D image to capturing it as a 3D model there is no longer a single privileged viewpoint on that object. The basis of the 3D scanning techniques you mention, ‘photogrammetry’, is a principle that for most of the twentieth century was considered only as a passing amusement in the prehistory of photography: the stereoscope. An extraordinarily prescient account of the potential of stereoscopic photography was published in the mid-nineteenth century by the American physician Oliver Wendell Holmes. In his 1859 essay The Stereoscope and the Stereograph Holmes writes:

Form is henceforth divorced from matter. In fact, matter as a visible object is of no great use any longer, except as the mould on which form is shaped. Give us a few negatives of a thing worth seeing, taken from different points of view, and that is all we want of it. … Men will [soon] hunt all … objects, as they hunt the cattle in South America, for their skins, and leave the carcasses as of little worth.

MG: You also mentioned during the talk that in a gallery situation you produce the sequence of the work in a non-linear narrative form, such as with A Place to Read and Hôtel Berlin. Hence, at any point the viewer can enter into the work, and every framed image, every word can be the first. There is a certain democratic process to an autonomous experience of images; text and sound that are simultaneously significant at any given time. Consciously and unconsciously how do you think this experience is registered and absorbed by the audience?

VB: Although it is possible to enter a movie theatre after the film has begun, and leave before it ends, it is normally assumed that the duration of the film will coincide with the duration of the spectator’s viewing of it. In the gallery it is normally assumed that these two times will not coincide, as visitors to galleries usually enter and leave at unpredictable intervals. My moving image works are therefore designed to loop, with a seamless transition between first and last frames. As any element in the loop – image, text, sound – may be the ‘first’ to be experienced by the visitor then the elements that comprise the work should ideally be independently significant. In this, the experience of a moving image work designed specifically for a gallery setting is closer to that of a psychoanalytic session than to a narrative film: no detail of the material produced in an analysis is considered a priori more significant than any other, all elements equally are potential points of departure for chains of associations. The psychoanalysts Jean Laplanche and Serge Leclaire describe the reiterative fractional chains that form daydreams and unconscious fantasies as “short sequences, most often fragmentary, circular and repetitive”, and characterise the fantasy as a “scenario with multiple entry points”. This is exactly how I think of my works. In all, the conditions of spectatorship of moving image works made for the gallery are closer to those traditionally associated with painting than to those associated with cinema. The ideal viewer is one who accumulates her or his knowledge of the work, as it were, in ‘layers’ – much as a painting may be created. Barthes remarked that at the cinema “you are not allowed to close your eyes”. Gaps and silences are integral to my own works as spaces in which the associative processes of the viewer may be actively solicited, albeit I myself have no way of knowing what these may be. Duchamp said, “paintings are made by those who look at them”. In this sense there are as many paintings as there are viewers – as the meaning of an artwork, unlike that of a traffic sign, is necessarily incomplete. Its meaning is not specified in advance but depends on the active participation of the individual reader, who of course is free to withhold that participation.

MG: You produced a work in Berlin at Tempelhof Airport entitled Hôtel Berlin in 2009. The airport, developed by the Nazis, is a rhetorical, monumental construction and represents just one building in Hitler’s dream city of Germania. The airport is loaded with meaning and fascinating by virtue of our moral dilemma towards the question; can we take pleasure in looking at a building built by the Nazis? Hôtel Berlin brings together associations of history, memory and desire in an exhibition that interplays again with film, text and still images. Can you elaborate on this particular project and what you discovered during the process of bringing the work together?

VB: In most of my works the objective appearance and history of a place is refracted through a prism of subjective associations. Invited to make a work in Berlin I turned to the former Tempelhof Airport as an allegory of the condition of the city that contains it – on the cusp between a devastating past and an uncertain future. The architect of the Tempelhof building complex was Ernst Sagebiel, who joined the Nazi party in 1933 and received the Tempelhof commission from Albert Speer in 1934. From 1929-32 Sagebiel had been project leader in the Berlin office of Eric Mendelsohn, who in 1914 had sketched an ‘aerodrome’ – a huge building with a curving plan and a tall central hall for airships – and explicit echoes of Mendelsohn’s visual vocabulary may be found in Sagebiel’s design for Tempelhof. In the course of my research I came across this passage from one of Mendelsohn’s letters: “I am completely absorbed. I scarcely breathe, eat little, sleep among visions of towering buildings and am wholly preoccupied.” The passage led me to think of ‘Mister X’, the eponymous architect hero of a 1980s comic book who believes that the psychical ills of large cities are architectural in origin, and who devises a system of architectural geometry – ‘psychetecture’ – that will induce universal social harmony. Mister X embodies his psychetectural principles in the plans of a new city, ‘Radiant City’, but his profiteering partner hires cheap contractors to literally ‘cut corners’. With its geometry perverted Radiant City breeds psychosis in its inhabitants and violent chaos ensues. In his unceasing efforts to undo the damage Mister X invents a drug, ‘insomnalin’, that will allow him to go without sleep, and is found perpetually muttering: ‘So much to do, so little time to do it’. In my fantasy the violent chaos of Radiant City merges with the real history of Tempelhof. When Soviet troops arrived there, in April 1945, they used explosive charges to blast open heavy steel doors in the basement levels – unwittingly igniting the vast film archive that the Wehrmacht had stored there. As Spiegel Online reports: “The valuable celluloid burned for days, and the walls have remained blackened to this day.” Spiegel’s account of Tempelhof also tells of the comings and goings in the 1960s of such luminaries as Marlene Dietrich, Billy Wilder, Gary Cooper, Marilyn Monroe and Romy Schneider. The Tempelhof complex contains a hotel. In my associative fantasy the entirety of Tempelhof becomes a vast ‘airportel’ and an archive of memories of film scenes set in hotel rooms. As the obsessively driven figure of Mendelsohn/Mister X stalks the deserted corridors of ‘Hôtel Berlin’ I imagined such scenes repeating themselves endlessly behind its many doors: Last Year in Marienbad, Vertigo, The Passenger, Alphaville …

MG: What are the conceptual factors involved when you make decisions about the use of colour or monochrome with your works?

VB: I could find intellectual reasons for such decisions, but in practice they’re largely intuitive. Having said this, I should add that – as I said in relation to the image sequences in A Place to Read – my aesthetic preferences are largely governed by criteria of economy. Does colour add more than purely anecdotal information? If not then I prefer to leave it out. To stay with the Istanbul example: what you characterised as the ‘drone’ shot circling the coffee house is there to show you the structure of the building – so I took the colour out of it as an irrelevant distraction from what I was trying to get the viewer to understand. On the other hand, the sequence of the movement down the path through the garden absolutely had to be in colour, to invoke a somewhat Disneyesque idealisation of the setting.

MG: There is an apparent yet interesting paradox in your thinking. You have written and talked about the importance of ‘considerations of specificity’ at a time since postmodernism appeared to erode and break down the relevance of specificity and instead replace and merge hybridity and pastiche in a melting pot of culture. Your own practice appears to embrace this disappearance of distinctions with your use of various media. And yet you argue that specificity is unavoidable in any art practice, and that you take this into account with your own work. What exactly do you mean by this?

VB: I’ve written at some length about considerations of specificity and it’s difficult to give a short answer as there are several different aspects to specificity. One of these emerges in 1746 when the expression ‘Fine Arts’ first enters language in the title of an aesthetic treatise by the French philosopher Charles Batteux. In Les beaux-arts réduits à un même principe (‘the fine arts reduced to a single principle’) Batteux argued that music, painting, poetry, sculpture and dance share a common aim – the imitation of what is beautiful in nature – which differentiates them from other arts. Two decades later, in his book of 1766 Laocoön the German philosopher and dramatist Gotthold Ephraim Lessing traced a line of demarcation within these practices. Rejecting a literary approach to painting, inherited from classical antiquity and institutionalised in the art academies of his day, Lessing drew a fundamental distinction between poetry and painting: the former art is extended in time, while the latter is extended in space. The specificity of the practice of a ‘fine art’ was now to be defined not only in terms of its ‘external’ relations to the society that contained it but also in terms of its inherent formal conditions. In the twentieth-century the idea that an art practice is to be specified primarily by what formally differentiates it from the practices around it became paramount in Modernist aesthetics. For example, in his influential essay of 1961 Modernist Painting, the American art critic Clement Greenberg wrote: “Because flatness was the only condition painting shared with no other art, Modernist painting oriented itself to flatness as it did to nothing else”; consequently, he concluded, “content is to be avoided like a plague”. By the end of the twentieth-century however, as you say, what might once have been considered defining differences between the various art forms, and between art practices and other practices, became routinely ignored in a ‘postmodern’ celebration of pastiche and hybridity. The arrival of digital technologies further eroded formerly categorical distinctions between art practices – most conspicuously photography, film and video – by placing their material means of production on the same technological basis. Today, questions of specificity, what it is that distinguishes art in general from other practices in society, and what it is that distinguishes one art practice from another – questions foundational to the Western concept of ‘fine arts’ – have become largely elided from consciousness.

To keep things in the context of our exchange let’s turn from the general field of art to the ‘specific’ case of photographic specificity. In the only article Greenberg wrote about photography he said that the specificity of photography resides in its ability to tell a story. As other arts also fulfill this function we may assume he was speaking of what differentiates a photographic image from the purportedly ‘content free’ Modernist painting he championed. The critical hegemony of Greenbergian Modernism was broken in the mid-1960s with the advent of Minimalism. The fiercest opponent of Minimalism was Clement Greenberg’s follower, the art critic and historian Michael Fried. Fried more recently revived the arguments he used to defend Modernism against Minimalism to champion contemporary forms of photographic Pictorialism. Not the least of the historical ironies here is that the acceptance of photography in the art world today is due almost entirely to the radical attention given to photography in the ‘Conceptual Art’ that evolved out of Minimalism in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In extensively borrowing from painting – from conventions of ‘genre’, through compositional schemas, to large physical size – neo-Pictorialist photography is by definition indifferent to considerations of specificity. Certainly the specificity of photography cannot be defined in the terms in which Greenberg first defined the specificity of painting – ‘medium-specificity’. If, according to Greenberg, the medium of painting is paint, applied to a flat support (canvas or board), then it might most strictly follow that the medium of photography is photosensitive emulsion, applied to a flat support (glass or acetate). But such a definition would evict the camera itself from the scene, reducing photography to, literally, photo-graphy: drawing with light (as in, for example, the ‘photogram’). As a consequence I once argued that the specificity of photography lay not in its medium but in its apparatus – the still camera – and most especially in the speed of this apparatus in registering the fleeting appearances of the world. It seemed to me at that time that the genre of ‘street photography’ best exploited the specificity of photography, in that it produced results that no other art form could replicate. Today, an air of anachronism and nostalgia hangs about the expression ‘still camera’. Because the distinction between still and moving images is no longer definitive, because cameras are nodes in the Internet, because the distinction between camera and projector is no longer definitive, because the camera has dematerialised, for these and no doubt other reasons we can no longer claim that the specificity of photography is in its apparatus. Today, the photographic apparatus is no longer specific to photography, the specificity of photography now is in its apparatus. If this sounds confused, blame the English language. French has different words – appareil and dispositif – for the two meanings of the English word ‘apparatus’ used here. In questions put to him in 1977, following the publication of the first volume of his History of Sexuality, Michel Foucault was asked to explain what he meant by the word ‘apparatus’ (dispositif) when speaking of the ‘apparatus of sexuality’. He replies:

… firstly, a thoroughly heterogeneous ensemble consisting of discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions … the said as much as the unsaid. Such are the elements of the apparatus. The apparatus itself is the system of relations that can be established between these elements.

Foucault goes on to say that the apparatus is articulated within systems of power and the ‘epistemic’ – the shifting grounds of what counts as legitimate knowledge in a particular society at a particular time. If we were to identify the components of the photographic ‘apparatus’ in Foucauldian terms we might begin by making lists under the headings that Foucault himself provides. For example, under ‘discourses’ we would enumerate the various bodies of speech and writing that take ‘photography’ as their object: technical, historical, sociological, philosophical, curatorial, critical, journalistic and so on. Under ‘institutions’ we would list not only such entities as The Royal Photographic Society, The Photographers’ Gallery, and Photography Departments in art schools and universities, but also such things as the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize and other instruments of legitimation. The category ‘architectural forms’ would include the various types of structures within which photographs are presented: such as billboards and plasma screens, art museums and galleries, magazines and newspapers, and the Internet. It is obvious to commonsense that photographic discourses, institutions, and so on, all converge upon a singular common object that has given rise to them all: ‘photography’. But this putative singularity is in fact a mutating techno-socio-phenomenological jigsaw incapable of forming coherent pictures without discursive framing. It is the apparatus alone that now produces ‘photography’ in its various specifications, including of course the category ‘art photography’. I have remarked that Foucault first used the term ‘apparatus’ in relation to his discussion of the production of the category ‘sexuality’ – that is to say, the production of ‘knowledge’ of sexuality. For Foucault, the production of knowledge is inseparable from the production of power – but a power that is always diffuse, a matter of what he calls ‘capilliary action’, rather than something held and exercised from a central position. Economic power is part of the apparatus he specifies but is not determinant. A more deterministic idea of the ‘apparatus’ in the production of culture was earlier provided by Bertold Brecht. By ‘apparatus’ Brecht means every aspect of the means of cultural production – from technologies, through publicity and promotion, to the financial and political elites that bankroll and control the various cultural institutions. Brecht speaks of what he characterises as the ‘muddled thinking’ of artists and critics alike in respect of the apparatus. I shall cite him at length; he writes:

… by imagining that they have got hold of an apparatus which in fact has got hold of them they are supporting an apparatus which is out of their control, which is no longer (as they believe) a means of furthering output but has become an obstacle to output, and specifically to their own output as soon as it follows a new and original course which the apparatus finds awkward or opposed to its own aims. Their output then becomes a matter of delivering the goods. Values evolve which are based on the fodder principle. And this leads to a general habit of judging works of art by their suitability for the apparatus without ever judging the apparatus by its suitability for the work. People say, this or that is a good work; and they mean (but do not say) good for the apparatus. Yet this apparatus is conditioned by the society of the day and only accepts what can keep it going in that society. … Society absorbs via the apparatus whatever it needs in order to reproduce itself. This means that an innovation will pass if it is calculated to rejuvenate existing society, but not if it is going to change it …

MG: What project are you working on now? What can we look forward to seeing and reading next?

VB: In 2016 I was invited by an Italian publisher to contribute to a series of artists’ books on the common theme of ‘the afterlife’. I accepted on condition that my book not be in a ‘limited edition’ but published and distributed conventionally. With the passage of time the outcome has now been a limited edition work – mandarin – for the Italian series, and a larger conventionally produced book – Afterlife – published by Thomas Zander / Walther König. Both books emerge from the same ‘conceit’ (as one might have said in the eighteenth century) of a parallel world much like our own but with the exception that technology allows a digital copy of the mind. Once the copy is made there are two individuals – one organic, the other numeric. Each will evolve separately, but only one will die. I hope that, as a science fiction scenario, the idea is sufficiently familiar to serve as ‘pre-text’ (as we liked to say in the ’70s) for its allegorical dimensions. For me, ‘Afterlife’ is simply our fractured everyday existence in algorithmic society, with its various digital doublings of ourselves and its recastings of the operations of memory. With this latest work I finally got around to dealing with a ‘contradiction’ that had been bothering me for some time. My texts and images are all produced in computer space, so in principle may be distributed in that same space, made freely available to anyone with Internet access. I worked with a web programmer (rather than a web designer) to clear a quiet space in the cacophony of the Internet where Afterlife may now be accessed in a web-based form. At the same time, I was working with the specificity of the book in mind. The book has heft when held in the hand and the work is experienced in the act of turning the pages. Having first decided on the physical dimensions, I considered the overall rhythm of the reading experience. Essential to this are the spaces between elements, which I think of in terms of the Japanese concept of ma. The ma is the interval, both spatial and temporal, between two successive events – an interval charged with the meaning produced in this succession. I work with the ma between two psychological events: the image formed while reading the text, and the image formed while looking at the picture. This is true of all my work. I’m now thinking about another ‘chapter’ of the project for an exhibition in New York next year – this time conceived for the specificity of the gallery. Concurrently with this ongoing project my most recent critical essay was commissioned for an Amsterdam University series on ‘Key Debates in Cinema Studies’. The editors have entitled the forthcoming volume Post-cinema. Cinema in the post-art era. I took the title at face value as a symptom of changes taking place under the impact of computerisation not only in the general environment of representations but in cultural institutions, which I see as fragmenting and coalescing into new formations. At the end of the essay I suggest that, faced with the diversity of image practices consequent upon digitalisation, we might perform a quasi-phenomenological epoché – a putting aside of what one ‘knows’ – in which such categories as ‘cinema’ and ‘art’ are ‘bracketed out’ in order to better understand what new cultural categories may be forming. I would recommend a similar ‘putting on the shelf’ of what we know of ‘photography’, of what we endlessly repeat as photography, to allow a clearer view of what camera practices may now be emerging – regardless of what we may think of them. In this I agree with Brecht’s observation that there are times when we must begin “not with the good old things, but with the bad new ones”. ♦

Image © Michael Grieve