Mimi Mollica

Terra Nostra

Book review by Gerry Badger

In what might be one of the most heartfelt moments on British television, in the middle of a feelgood programme about art and food in Sicily, star Italian chef Giorgio Locatelli took art-critic Andrew Graham-Dixon to a hillside outside Palermo, overlooking a motorway. He proceeded to talk about how the Cosa Nostra, the Sicilian mafia, murdered the anti-mafia judge, Giovanni Falcone, in 1992. This is “the hole in the heart of Italy,” he said with great feeling.

This is the subject of Mimi Mollica’s book Terra Nostra, published by Dewi Lewis. The hidden subject, because although the mafia is everywhere, its impact is felt rather then seen. It is woven into Italian society. In September 1987, the then Prime Minister, Giulio Andreotti, head of the Christian Democrat party that ruled Italy for decades, was alleged to have had a secret meeting with the ‘capo dei capi’ of the Cosa Nostra, Salvatore Riina. The fact that Andreotti was later absolved of any mafia association does not alter the fact that, as Peter Robb has written, the mafia was (or is) a state within a state, a “state that maintained relations with professional, political and judicial representatives of that other state, the Italian republic.”

The most notable body of work about the Sicilian mafia previously has been the photojournalism of Letizia Battaglia, who worked for the anti-fascist newspaper L’Ora, and photographed the results of the high years of mafia violence from the 1970s to the 90s. Firstly, she photographed the bloodied corpses on the streets, and then the mafiosi themselves, kicking and spitting at the photographer as they were taken to trial. A photograph in her files of the aforementioned Andreotti meeting mafia boss Antonio Nino Salvo, helped frame the indictment though it did not secure the conviction. And of course, though it is not Sicily, but most definitely related, Milanese photographer Valerio Spada photographed the Camorra, the Neapolitan mafia, making portraits of young mafiosi in the notorious suburb of Scampia.

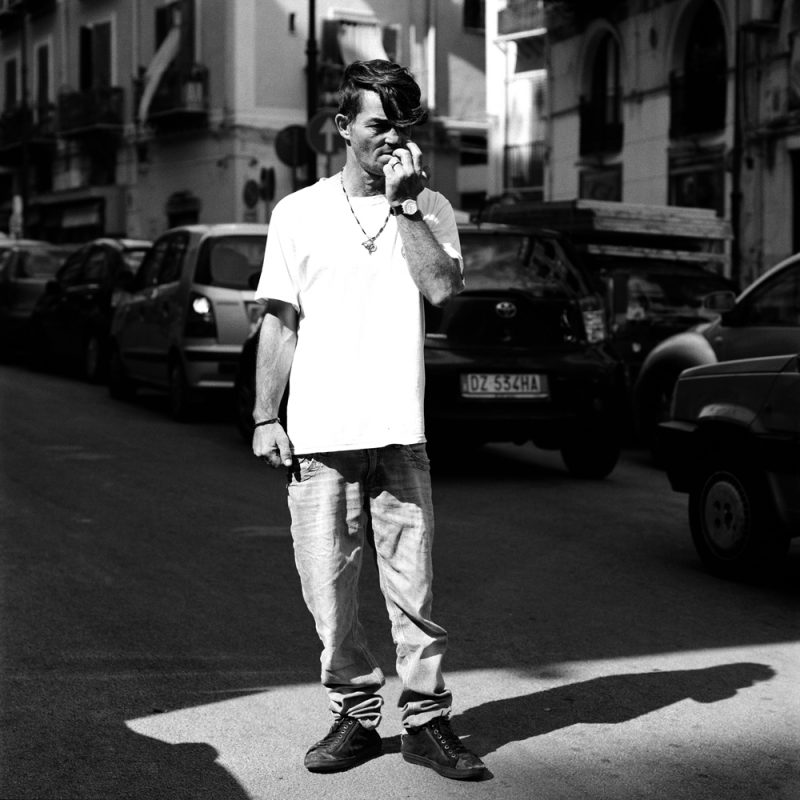

But that is not Mimi Mollica’s way. Terra Nostra is much more indirect. There is not a young thug or a bloodied corpse to be seen. In a series of landscapes and street portraits, we see Sicily as one might see it as a visitor – an attentive and knowing visitor at least – or as a resident sees it every day. In short, Mollica is photographing the surface, that which you can see, which is all any photographer can do, but like any good photographer, is suggesting this recent history with metaphor and symbol. So there are images that suggest violence, others that suggest suspicion and secrecy, some that suggest great beauty, some that suggest ugliness and environmental degradation.

This book tells its tale in an oblique way. But one thing is clear. Sicily is an island apart from Italy, part of the country and yet not part of it. And there are different parts of Sicily. Mollica is dealing with the western part, from Palermo in the north, round the west coast to Agrigento in the south. The eastern part of the island, and cities like Catania and Syracuse, are somewhat different.

In a way the book begins at the end. Two signs on a wall read ‘uscita’ (exit) though the way out is not clear. The first metaphor. Then the final image is a barred gate, as if to say once Sicily takes hold of you it will not let go. Or is this a circular narrative? Are both images asking whether there is a way out for Sicily. As Mollica says, Sicily seems caught between “paradise and hell.”

The book’s portraits are also very strong. As Sean O’Hagan remarks in his text, they have this insidious sideways glance quality. And far from displaying Mediterranean exuberance, which is something of a myth anyway, many exude an air of self-containment that amounts to suspicion – and this in photographs that were taken more or less on the fly. The cover picture, of a scarred, gaunt old man standing at a vandalised bus-stop, clutching his briefcase like grim death, says it all. John Szarkowski once said of a Brassai portrait that it was “full of wormwood.” Of course he never saw this one. ‘If looks could kill’ was never more appropriate.

There is something terrible implied in this image. Elsewhere, the symbols of violence and machiavellian plotting are more overt. A wreath lies in a road. A group of politicians huddle together in a conspiratorial group. A price tag skewers the eye of a tuna on a market stall. And a man who seems to taking a picture on a mobile phone is crouched in the position they teach at gun school.

But the most obvious damage is perpetrated upon the landscape. The legacy of the mafia in the 1970s and 80s was a rampant boom in unbridled real estate development, much of it unchecked and yet funded by development grants. Little was finished, so Sicily, especially in the west of the island, is littered with abandoned, half-built construction sites. One particularly memorable image in Terra Nostra, of unfinished villas littering a hillside, looks like an aerial shot of the ruins of Hiroshima. And the jewel in Sicily’s tourist crown, the Valley of the Temples at Agrigento, is not quite what it seems in tourist posters as a result of encroaching development.

This construction, so wasteful and unsightly, scars the landscape, the last invader to make its mark upon this much conquered island. It is so unnecessary, as so much Sicilian real estate has the ‘vendisi’ (for sale) attached. For instance, last year I saw three beautiful Baroque palazzi side by side, requiring attention on a grand scale, awaiting offers in the beautiful historic city of Noto, as well as many other time-worn properties both large and small.

There is a lot of explanatory text in Terra Nostra, essays by Roberto Scarpinato and Sean O’Hagan as well as captions to the pictures. This is necessary to fill in a complex political and social background. Nevertheless, Mimi Mollica’s photographs certainly stand by themselves. They are eloquent and poetic, and in an era where so much photography is trite and shallow, dense enough to feed both mind and eye. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Mimi Mollica

—

Gerry Badger is a photographer, architect and photography critic of more than 30 years. His published books include Collecting Photography (2003) and monographs on John Gossage and Stephen Shore, as well as Phaidon’s 55s on Chris Killip (2001) and Eugene Atget (2001). In 2007 he published The Genius of Photography, the book of the BBC television series of the same name, and in 2010 The Pleasures of Good Photographs, an anthology of essays that was awarded the 2011 Infinity Writers’ Award from the International Center of Photography, New York. He also co-authored The Photobook: A History, Vol I, II and III with Martin Parr.