Writer Conversations #3

Joanna Zylinska

Joanna Zylinska is an artist, writer, curator and Professor of Media Philosophy + Critical Digital Practice at King’s College London. She is an author of a number of books, including AI Art: Machine Visions and Warped Dreams (Open Humanities Press, 2020) and Nonhuman Photography (MIT Press, 2017). She also co-edited open-access works, Photomediations: An Open Book and Photomediations: A Reader, as part of the Europeana Space project funded by the European Commission. Her art practice involves experimenting with different kinds of image-based media. In 2013, she was Artistic Director of Transitio_MX05 Biomediations, the biggest Latin American new media festival, which took place in Mexico City. She is currently researching perception and cognition as boundary zones between human and machine intelligence, whilst trying to answer the question: ‘Does photography have a future?’.

At what point did you start to write about photographs?

I came to writing about photography (rather than just photographs) relatively late in my career. I had been working as a media academic at Goldsmiths, University of London, teaching the philosophical and cultural aspects of digital media for many years. I had also had an active research interest in art, particularly new media art. But photography had been my secret love, something I had practiced “on the side”, so to speak, but that I hadn’t brought into any of my more “proper” academic work. It all changed in 2007, when, still working at Goldsmiths, I decided to enrol on a practice-based MA in photography at the University of Westminster. I did that a little bit in secret too! Doing that MA changed everything. It encouraged me to start incorporating practice into my written work, to change the way I write and to address photography more comprehensively as a key medium of our times. It also led me to develop a new philosophy of photography, culminating in my book, Nonhuman Photography (2017). (Analysing photographs that were not of, by or for the human, that book looked at the photographic medium across the scale of so-called ‘deep time’. It positioned various ‘impressioning’ practices, from fossils through to tanning, as forms of photographic practice, alongside its more conventional forms such as photograms, analogue film frames or digital snapshots.)

What is your writing process?

Because I try to maintain that dual track of having an image-based practice as well as working on photography philosophically, I am very mindful that writing about photography shouldn’t use photographs just as illustrations. Rather, in recognition of photography’s agency, I would say that I write with photographs. Often these will be projects by other people (artworks, social media practices) or social and technical networks in which photographs play an active role (Internet search engines, image databases for training AI algorithms). But I also try to develop some aspects of my theoretical argument from photographic practice. So I often start with an idea and a project – like with Active Perceptual Systems, where I wore a necklace-like Autographer camera for two years whilst writing about nonhuman vision, or when I hired workers from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk labour platform to take a photo from the window of the room they were in with a view to creating a collective portrait of invisible ‘undigital’ global workforce, as part of my work on AI and art. So, in my work, I try to get writing and image-based practice to speak to each other, to push each other and then also, inevitably, to converge.

What are the questions or problems that motivate your writing?

The primary concern of my work over the years has been the constitution of the human as both a species and a historical subject. Adopting this geological probe of ‘deep time’ mentioned earlier, I have looked at the emergence of the human in conjunction with the surrounding technologies, such as tools and other artefacts but also communication in its various modes – be it everyday language, storytelling, ethics, art and, last but not least, photography. In an attempt to challenge human exceptionalism without giving up on my own curiosity about my phylogenetic kin (i.e., other people), in my writing, I zoom in on the signal points of the human such as intelligence, consciousness and perception. With this, I aim to explore the entanglements of human and nonhuman forms of intelligence, including the promises and threats offered by AI and machine vision. Currently, I am working on perception as arguably the key mode of engagement with the world in different species. This project involves looking at the reconfiguration of ‘the eye’ in the digital age and at the humanist blind spot in machine vision. As part of this work, I am investigating the role played by images, especially mechanically-produced images such as photographs, in human becoming. Looking at the transformation of photography by computation – and the transformation of human perception by algorithmically-driven images, from CGI to AI – I am also trying to figure out what it means to live surrounded by image flows and machine eyes. This radical transformation of the photographic medium is currently leading me to explore a question which is also a provocation: ‘Does photography have a future?’

Does your concern for writing about positions beyond anthropocentrism impact on how you write? Is there a way to write beyond our human positionality?

My work is produced from within the theoretical standpoint recognised as critical posthumanism, a position that does not mean any straightforward overcoming of the human (were such a thing even possible), but that rather involves a rewriting or re-enactment of the human under the conditions of the planetary crisis resulting from the nexus of colonialism, globalisation, technoscience, late capitalism and climate change. You could say that I’m trying to write myself out of the conceptual and political strictures of humanism, with its constitutive forms of violence. I’m trying to accomplish this both in the content of my writings and in its style – which is often hesitant, minimal as well as ironic. This attempt also involves mixing different genres, different modes of enquiry and different media. At the same time, I’m aware that, even though many animals are known to leave traces – i.e. surface marks which could be seen as forms of inscription – grammatological writing is a specifically human practice; a practice that both makes sense to and is valued by humans. So, I’m also writing in full recognition of writing being a species-specific behaviour to which we humans have assigned a particular cultural value (a value which I of course also hold dear).

What is the role of writing in relation to what you have described as photography’s proximity to extinction, to climate transformation? Is this, in part, a recognition that photography’s industrial conditions feed into extinction whilst representing it?

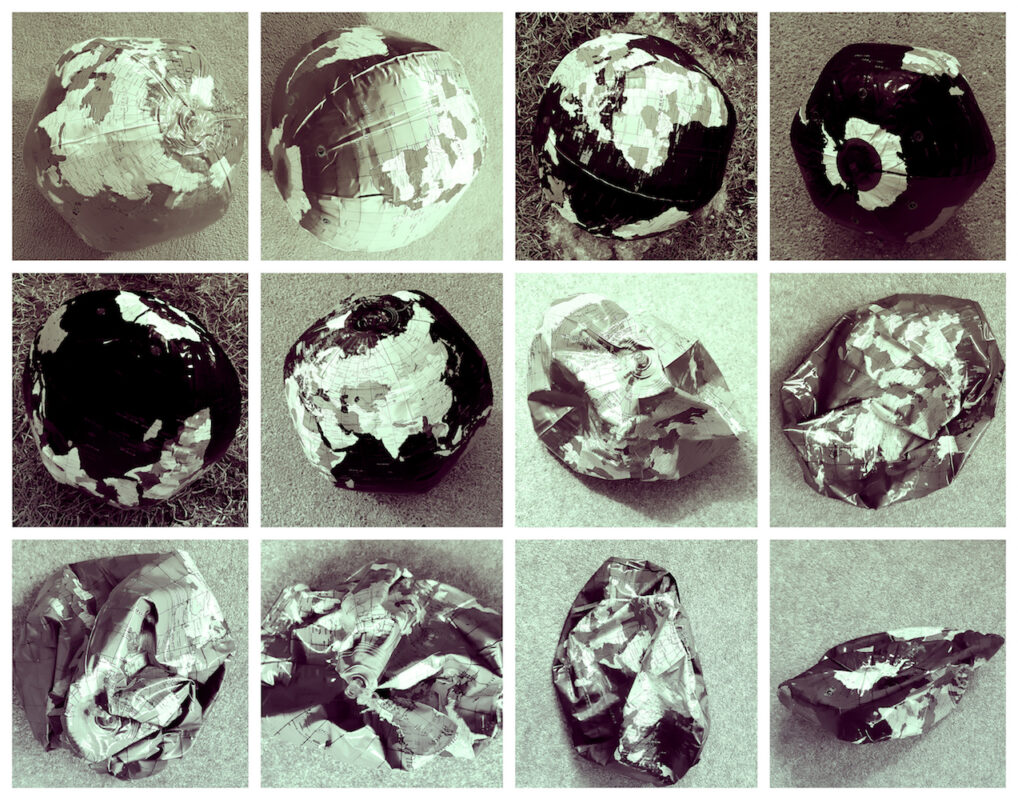

My work, both written and image-based, is indeed produced within the horizon of extinction, which represents the awareness of the eventual expiration of the human species and other species alongside us, and of our planet as a whole. But it’s also driven by a sense of urgency prompted by the foreshortening of this horizon as a result of the destructive human impact on planet Earth. Photography has of course been part of this impact – from the extraction of minerals needed to produce cameras and the use of harmful photochemical materials through to photography’s participation in the extractive data economy which is extremely resource-heavy (even if it’s sold to us through images of immaterial flows and clouds). Yet photography, as you point out, has also been used to represent, record and challenge practices leading to this accelerated extinction. Last but not least, there’s an existential dimension to photography for me. Photography, a par excellence practice of imaging and imagination (i.e. a practice of copying, making likenesses, mapping, making mental pictures and ideating), can serve as a conduit for asking bigger questions about our own ‘thrownness’ in the world – of which we are only temporary inhabitants – and of imagining different futures for ourselves and our planet. This future-oriented horizon of extinction, beyond the death of singular humans (be it that of Roland Barthes’ mother or our own), makes photography into what Swedish philosopher Amanda Lagerkvist has called ‘an existential medium’.

What kind of reader are you?

Committed, engaged, playful – but also forgetful. You could say that I read for an experience of an idea rather than for the purpose of constructing world systems out of the previously existing ideas.

How significant are theories and histories of photography now that curation is so prominent?

My previous answer might signify that I don’t care much about historical unfoldings and coherent linear trajectories. But this couldn’t be further from the truth. I recognise that meaningful photographic curation requires expertise, which needs to involve familiarity with theories and histories of photography. We also have to remember that these theories and histories are already forms of curation – and that they can be rewritten, restaged, rearranged.

What qualities do you admire in other writers?

A mixture of rigour and vitality and a desire to say something interesting and new about the world. I appreciate writers who have an awareness of their own writerly task – and who take this task (but not necessarily themselves, under the guise of ‘Here I Am as a Great Writer Speaking to You My Dear Reader’) seriously. My ideal writerly voice would be Roland Barthes from A Lover’s Discourse (1977) – but not, for the love of God, Camera Lucida (1980) – hybridised with Donna Haraway and Rebecca Solnit, and then remixed through some postcolonial epistemologies and affects, such as those coming from Eduardo Viveiros de Castro.

What texts have influenced you the most?

There are so many – from texts on photography by writers such as Vilém Flusser, Geoffrey Batchen and Tina M. Campt, through to those whose authors have shown me the way with words and concepts: Jacques Derrida, Hélène Cixous, Tim Ingold, Juhani Pallasmaa, Stanisław Lem. The book I wish I had written myself is Pandora’s Camera: Photogr@phy After Photography (2014) by Joan Fontcuberta.

What is the place of criticality in photography writing now?

We now live in image flows – we are surrounded by photographs on screens large and small, and are mediating our relationships with others through images. Photographs and other images form a transparent layer through which we see the world. I am increasingly concerned about the fact that this layer remains largely unseen. So, for me, the function of criticality in photography writing would consist in drawing attention to that seemingly transparent photographic layer, to see it for what it is, for what it’s made of and for how it’s made. This would need to involve going beyond semiotic readings of individual images – although I believe there is still need for developing an image literacy of an interpretative kind. But it would also need to involve developing an understanding of image infrastructures and of the way those infrastructures are involved in shaping our socio-political reality today. With this, we could perhaps go so far as to argue not only that photography writing needs to include criticality but also that any form of critical theory and critical writing today needs to engage, seriously and profoundly, with photography.♦

Further interviews in the Writer Conversations series can be read here.

Click here to order your copy of the book

—

Writer Conversations is edited by Lucy Soutter (University of Westminster) and Duncan Wooldridge (Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London), upon the invitation of Tim Clark (1000 Words and The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University).

Images:

1-Joanna Zylinska

2-Book cover of Joanna Zylinska, Nonhuman Photography (MIT Press, 2017)

3-Book cover of Joanna Zylinska, Minimal Ethics for the Anthropocene (Open Humanities Press, 2014)

4-Joanna Zylinska, Planetary Exhalation, 2021