Curator Conversations #14

Holly Roussell

Holly Roussell is Swiss/American independent curator, museologist, and researcher with in-depth knowledge of contemporary art and photography from East Asia. She is a specialist in post-1976 Chinese contemporary art, avant-garde artist groups and exhibition histories. Roussell served as coordinator of the worldwide traveling exhibitions program and photography prize, the Prix Elysée, for the Musée de l’Elysée, Lausanne, from 2013-17. In 2017, she co-founded the Asia Photography Project, a non-profit curatorial collective and platform for photography from East Asia. As an independent curator, some recent projects include Stars星星1979 (co-curated with Dr. Wu Hung) for the Beijing OCAT Research Institute for Chinese contemporary art with accompanying publication; acting as curator for the 4th Shenzhen Independent Animation Biennale (2018) under the direction of Li Zhenhua; Pixy Liao Experimental Relationship at the Rencontres d’Arles (2019); Dai Jianyong: Judy Zhu at the Shanghai Centre of Photography (2019), Jimei x Arles Foto Festival (2018) and Lianzhou Foto Festival (2019) and the major publication and travelling exhibition project, Civilization: The Way We Live Now (co-curated with William A. Ewing) that toured the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, (2018), UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing (2019), NGV, Melbourne (2019), Auckland Art Gallery (2020), MUCEUM, Marseille (2021) and other venues. In 2020, Roussell joined the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul, South Korea as International Curatorial Researcher in residence. She lives and works in Suzhou, China.

What is it that attracts you to the exhibition form?

The exhibition form is a challenge. I am attracted to the process and the comprehensive nature of the exhibition. It often begins for me with an idea and an ideal: what is the purpose or direction of this project? What would this project look like if everything goes perfectly? Which artists or artworks should be part of it? Where could it be exhibited? As projects evolve, constraints begin to appear, and the ideal morphs into something new. It is about problem-solving, and that challenges not only your patience but also your idea – that original concept – along the way. This aspect is an unseen part of the exhibition for visitors, but they are the unknowing beneficiaries, because the challenges help you better formulate and understand your own concept. A curator creates rhythm in a space, to tell a story to the visitor.

Working primarily in contemporary photography, something else that attracts me to the exhibition form is that my role is often a technical and a creative one. It happens, perhaps more often than one would expect, that work on an exhibition will extend beyond the selection and disposition of artworks in space, but involve also the production methods of those artworks. An example of this sort of collaboration is my work with the Shanghai-based artist Coca Dai (戴建勇). He is an extraordinarily active photographer and a wonderful, eccentric book-maker. Most of his projects existed only as multiple versions of self-published photobooks or digital scans from his hundreds of thousands of negatives. I discovered these when we met in 2016. A few years later when I was invited to nominate artists for the Discovery Award at the Jimei x Arles festival, I seized the occasion to work with Coca. For that show, we worked together to translate a project conceived as a book using the exhibition form. We did so by designing an exhibition that combined both prints and “books” on the walls. Groupings of 10 to 30 images, printed on thick rice paper literally hung from the walls, becoming “mini-books” interspersed in a constellation of single prints distributed throughout the space. These “books” on the walls recalled his original project not only as a formal reference point, they also require a similar intimate engagement from the visitor. Once the visitor begins flipping the pages, they are drawn into the personal memories. The viewer must spend time interacting with the narrative one photograph at a time, which is as Coca intended – analogous to how these moments were lived.

What does it mean to be a curator in an age of image and information excess?

It means remaining focused. Nowadays there are limitless possibilities: exhibition ideas, artists to collaborate with, magazines, journals, conferences, etc. This greater access to information creates a sort of “weight” when you begin to build a project. There is pressure to know about everything going on everywhere in the world, to have an opinion about it, to go see every show, to read articles, to always be up to date. Sometimes I relate it to a treadmill that’s been turned up a bit too fast. You feel like you could fall off at any time.

Access is no longer the problem for a curator. What to do with that material, however, is challenging. It is our job to edit that information, to filter it, to be inclusive, to be discriminating (in a positive sense), to find artists that need support to share their vision and artworks that are meaningful.

I deal with this by creating frameworks for my projects. I think being a curator in an age of information excess means accepting you will not always have perfect balance in your exhibitions. You may not always reach the “ideal”. It means there will be more people with similar ideas to yours perhaps than ever before, because we all have greater access to information. It means reinventing yourself, homing in on your own specific focus as a curator to adapt to the needs of the current world.

What is the most invaluable skill required for a curator?

One skill? We have to be pretty polyvalent! I can’t speak for every curator, but for me it has been meticulous attention to detail, and cool-headed problem-solving. In recent years, I have begun travelling with my own laser level.

What was your route into curating?

My route into curating was first through a passion for art history and then, mentorship.

When I graduated from university, I knew I wanted to work in art, and specifically art from China. After two years of working various jobs (mostly unpaid, so we can call those “internships”) in Beijing I worked as an artist assistant, curatorial assistant for a photo-festival, and as a translator. I knew I wanted the experience of an institution and was very fortunate upon relocating to Europe in 2011 to join the Musée de l’Elysée as an intern in the External Affairs and Travelling Exhibitions Department. My work at the museum was not necessarily “curatorial”, but it related to everything surrounding exhibitions. When that internship finished, Pascal Hufschmid, my manager, and the department head at the time, was kind enough to connect me with someone he knew who was looking for an intern. Little did I know that person was going to be one of photography’s most distinguished curators, the former museum director, William A. Ewing.

William and I met for coffee one late morning in Switzerland in 2012. We had a mutual interest in representations of landscape (I had written my undergrad thesis on the role of the land in Chinese Revolutionary and Contemporary Art). We decided that day to begin working on our first project together, Landmark: The Fields of Landscape Photography. This was the first exhibition I ever worked on as a curator. Landmark was already well along in planning stages, William had the theme in mind for more than ten years, and he took me on as his assistant curator at the moment he had secured a venue. He was a fantastic mentor. He included me in every aspect moving forward from research, to contacting artists, to discussing which works would fit best in each section. He gave me a lot of responsibility and encouraged me to develop my own opinions about the artworks, the artists, and how it could all come together in the space. The timeline for the project was extremely short. We travelled to London only about six months later to install the show at the Somerset House.

It included work from more than 70 artists loaned directly from galleries, artists, and private collectors – it was all organised within that half year window. This was an incredibly formative experience in that it showed me how dynamic this profession could be with the right combination of powerful personal vision and logistical organisation.

After Landmark, I went on to complement my Art History degree with a Masters in Museology. That year I took a fixed position at the Musée de l’Elysée as coordinator of the photography prize and the travelling exhibitions programme. William and I continued to work together (mostly during weekends) and have produced – as co-curators – the exhibitions Works in Progress: Photography in China 2015 which was presented at the Folkwang Museum in Essen, and our ongoing travelling exhibition, Civilization: The Way We Live Now. In 2017, I officially left the Musée de l’Elysée to become an independent curator full time. Now, based in China, my time is entirely dedicated to research and exhibitions about contemporary photography and post-Mao Chinese art and the avant-garde.

What is the most memorable exhibition that you’ve visited?

I think it wouldn’t be honest to say one exhibition stands out transcendently for me. I try to visit as many exhibitions as I can, but there are also plenty I have wanted to see and been unable to make. Visiting shows is a professional activity – I look at how the space was used, the tone of the texts, the scope of the project, any new ways of interacting with the public, the use of vitrines, and so on. I also want to feel the discomfort of the details that impeded the effectiveness of a project. Every exhibition I visit teaches me something new about curating exhibitions. Recently, I saw an ambitious exhibition in Washington DC that was fantastic at the Hirshhorn curated by Stéphane Aquin, Manifesto: Art x Agency, and, a few years ago, Xu Bing’s retrospective at the UCCA curated by Phil Tinari as also standing out.

The visit, rather than a specific exhibition, that was the most memorable for me as a curator, however, was to an art district. In the summer of 2008, I travelled to Asia for the first time and visited the 798 Art District in Beijing. It was a sweltering day, and 798 is in the far north-east of the city (at that time not yet connected by metro) so we had to take a taxi. Without traffic, it’s at least 40 minutes from the second ring road (which includes many famous historical sites and the Forbidden City), but, with traffic, considerably longer. When we arrived, we found a mix of former East German-built Bauhaus style factory buildings and small boutiques stationed along narrow, dusty streets. Part of the zone was the art district, and other areas were abandoned lots, office buildings, or crumbling apartment blocks. We wandered around in the maze of buildings and tunnels, between the cavernous former factory spaces that serve as contemporary art galleries until we found a small brick building with glass windows covered in vines. It was a bit off the beaten track. At the time, this was one of ShanghART’s Beijing galleries – S Space. ShanghART was founded in 1996 in Shanghai by the Swiss expatriate Lorenz Helbling, and by 2008 it already had multiple spaces in Beijing and Shanghai. The gallery team took me through their stable of artists, presenting works by Geng Jianyi, Shi Yong, Birdhead, Zhao Bandi, Sun Xun, Zhang Ding, Zhou Tiehai etc. As a student of art history at the time, I couldn’t believe all this was going on and we knew nothing about it back at my university. I had never felt particularly drawn to contemporary art until that moment, and what I saw there literally changed everything. This was my introduction to contemporary art from China, and the catalyst to start learning Mandarin and relocate my life there a year later. I don’t think any visit to an exhibition has ever been so memorable.

What constitutes curatorial responsibility in the context within which you work?

I believe curatorial responsibility is about vision and respect.

First, it is necessary to understand the importance of your role within the art ecosystem. It isn’t enough to make exhibitions, meet artists and put up shows of their work. As a curator you have access to people, resources, and visibility – what will you do with it? That is our biggest responsibility. We should fight for artists whose work has substance and understand our responsibility to skillfully navigate a world rooted in churning trends and nepotism. We should aim to make statements with our projects, to help people to step back and reflect on the things we take for granted, and not simply produce shows that will increase our own individual visibility or fame.

Secondly, and, perhaps, less evident, I believe we also have a responsibility to respect other curators, researchers, and individuals with areas of expertise. We should be generous and collaborate rather than be competitive and exclusive.

Finally, as a foreign curator working in China with many Chinese artists, I feel there is a crucial responsibility to listen and not to allow my presuppositions to cloud my ability to understand a work. There are certain challenges working outside one’s own culture, and it can be tempting to want to classify an artist’s work as X or Y because those are ideas we recognise from our own cultural history and can comprehend, but, it is our responsibility to not allow cultural bias or reference systems to take over.

What is the one myth that you would like to dispel around being a curator?

One myth is that everyone who makes an exhibition is a curator. I don’t think making an exhibition is enough to claim to be a curator. Conversely, if we subscribe to an expanded notion of curating, making exhibitions is not necessarily a requisite. Making exhibitions necessitates some level of logistical, legal, relational, and financial fluency, but being a curator is a subjective profession; it is about the vision and the storytelling of one person, or a small group, guiding you along a path of ideas they have constructed for you. The curator is, in many ways, a creator of new content.

Often, the broader that person’s curiosity or interests are, potentially the more interesting the connections they can make to the art will be, and the better they will be at relating to their audience in new ways. As Anne d’Harnoncourt has said, “curators a(re) enablers, if you will, people who are crazy about art and they want to share their crazy with other people”.

What advice would you give to aspiring curators?

If you are working in photography, look all the time at everything you can. Look at books, look at exhibitions, look online at artists’ websites, look at magazines, look at advertisements, look at newspapers. Try to understand what the images are telling you. Which images move you? Have a vision. Why are you curating exhibitions? Why this artist? Why is it important? I think if you cannot answer these questions about an exhibition you are putting on, you should revisit your motives.♦

Further interviews in the Curator Conversations series can be read here.

Click here to order your copy of the book

—

Curator Conversations is part of a collaborative set of activities on photography curation and scholarship initiated by Tim Clark (1000 Words and The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University), Christopher Stewart (London College of Communication, University of the Arts London) and Esther Teichmann (Royal College of Art) that has included the symposium, Encounters: Photography and Curation, in 2018 and a ten week course, Photography and Curation, hosted by The Photographers’ Gallery, London in 2018-19.

Images:

1-Holly Roussell © Amber Tang

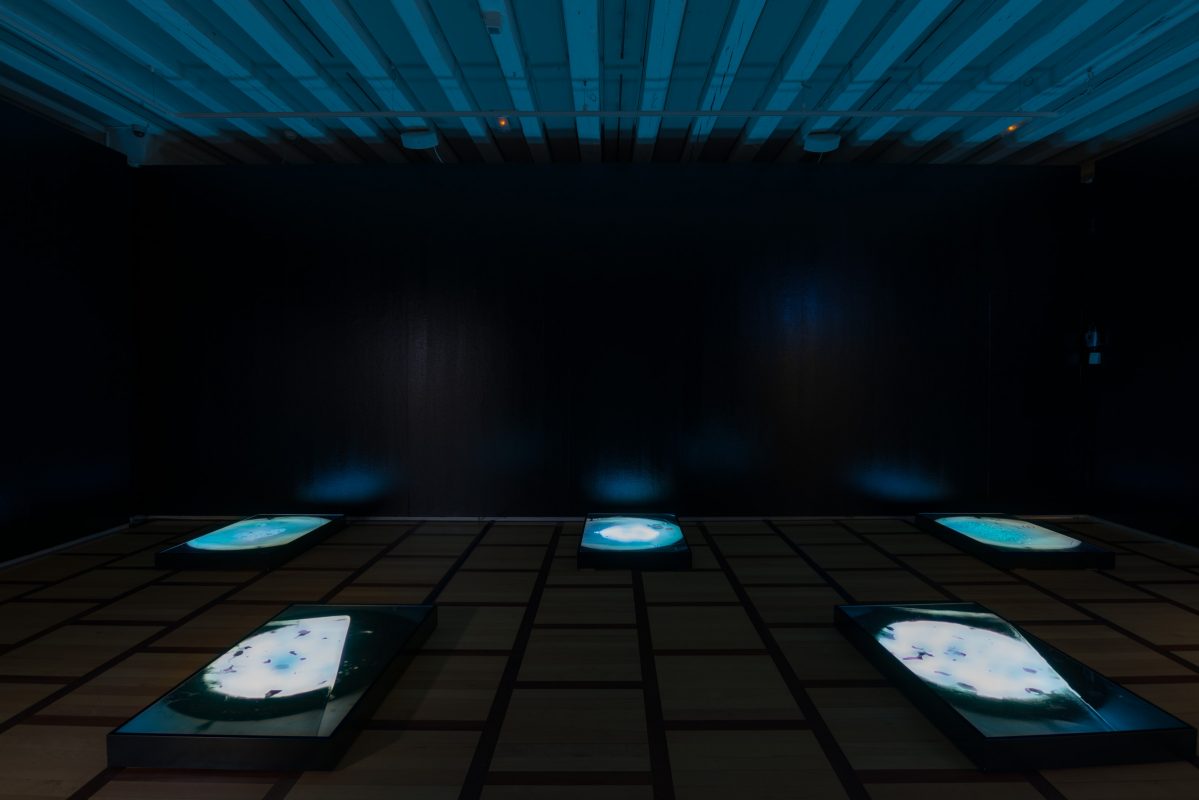

2-Installation view of Works in Progress: Photography in China at Folkwang Museum, Essen, 2015.

3-Installation view of Stars星星1979 at the Beijing OCAT Research Institute, Beijing, 2019.