Monika Orpik

Stepping Out Into This Almost Empty Road

Essay by Natasha Christia

Stepping Out Into This Almost Empty Road is the new body of work by photographer Monika Orpik set in the Białowieża Forest, a UNESCO World Heritage site at the frontier of Poland with Belarus. Transcending the dramatic twists of the ongoing political actuality in Eastern Europe, it is a stark political statement that calls attention to the ethical double standards currently applied to asylum seekers, depending on political agendas and a refugee’s place of origin, writes Natasha Christia.

Natasha Christia | Essay | 10 Aug 2023

Imprisoned by four walls

(to the North, the crystal of non-knowledge

a landscape to be invented

to the South, reflective memory

to the East, the mirror

to the West, stone and the song of silence)

I wrote messages but received no reply.

Octavio Paz, ‘Envoi’

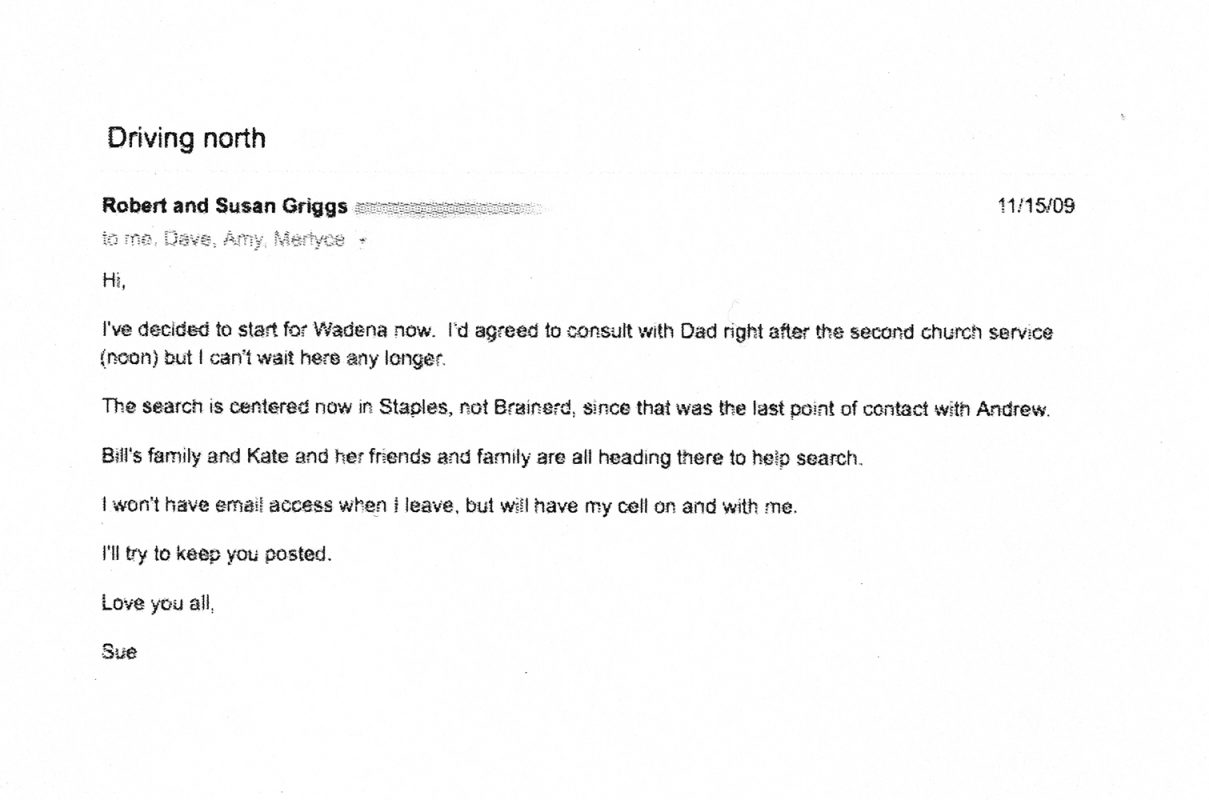

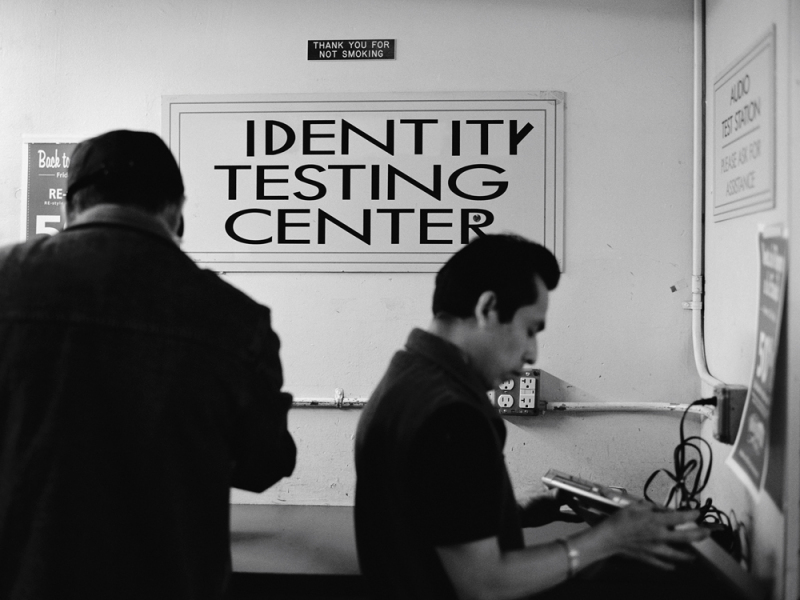

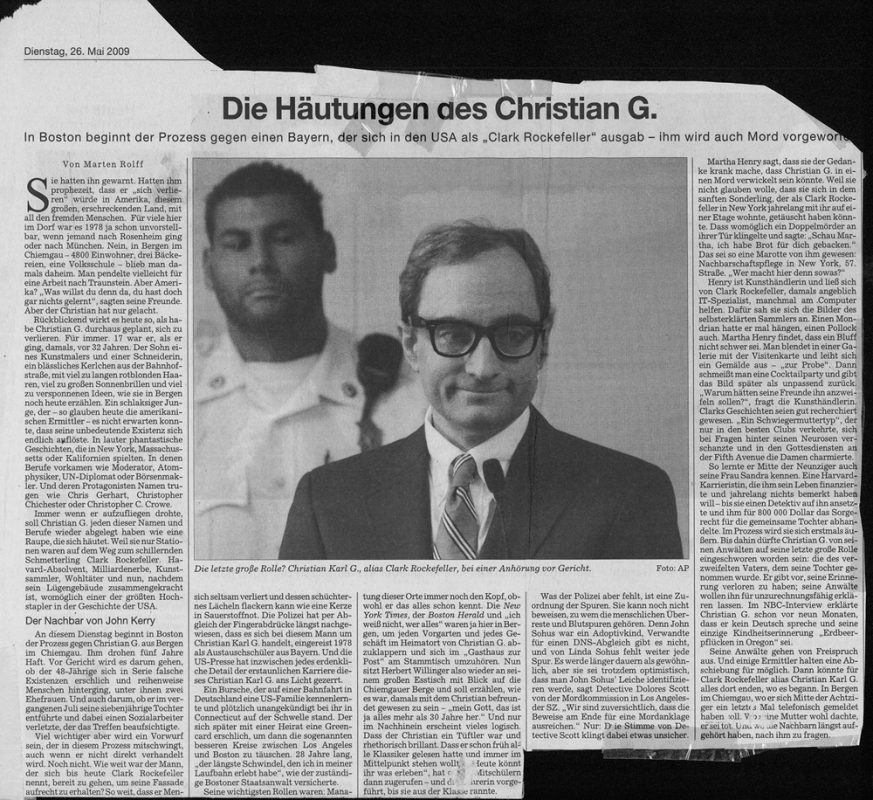

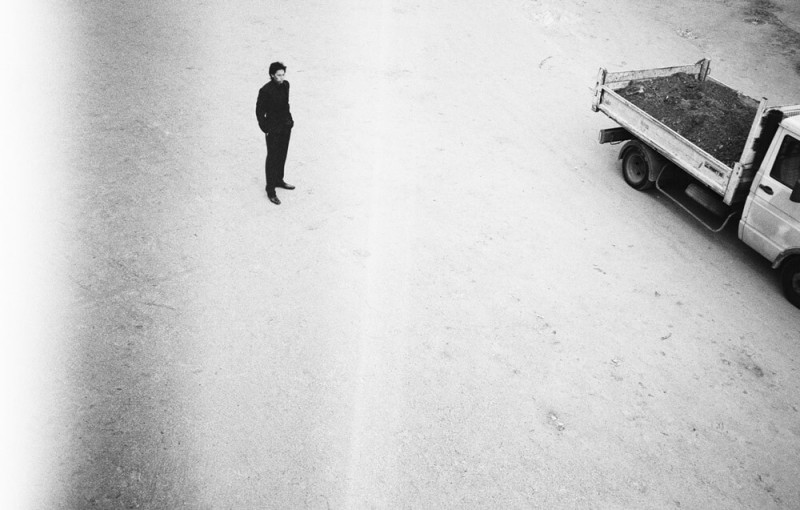

The borderland as an enclave of limbo, uncertainty, freedom and political oppression is the subject of Stepping Out Into This Almost Empty Road, the new photobook that Polish photographer Monika Orpik has edited with Łukasz Rusznica. Based on Orpik’s own photographs and a series of recollected testimonies, Stepping Out Into This Almost Empty Road takes the reader through the frontier of Poland with Belarus, where Orpik found herself in 2020 on a volunteer assignment for an NGO. In the course of three and a half months, she travelled through the Białowieża Forest, which straddles the border as an interterritorial natural boundary that separates and, at the same time, merges the two countries into one.

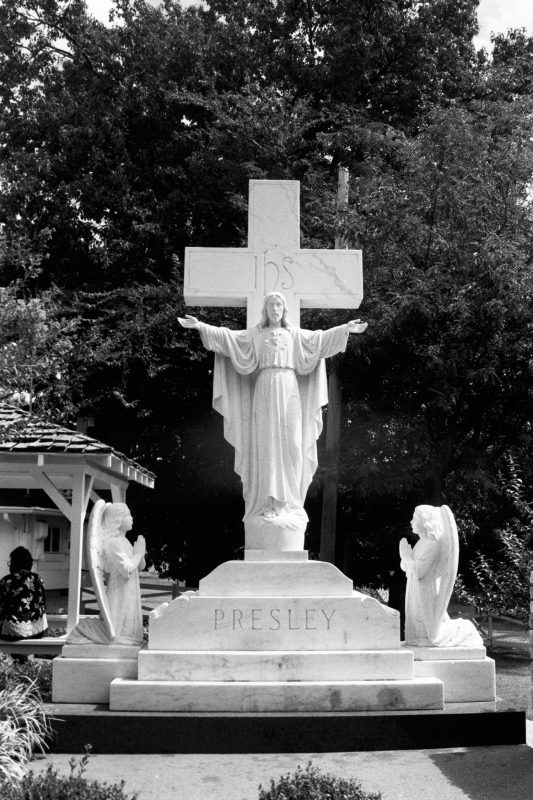

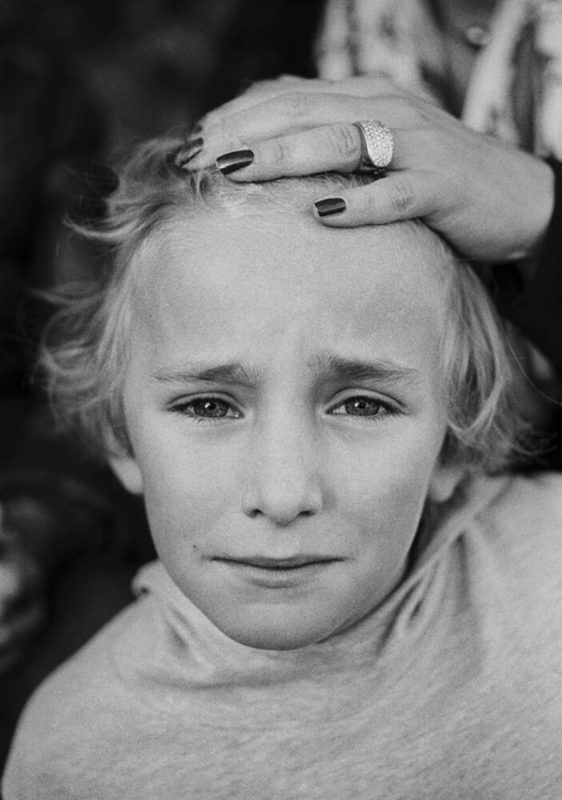

The Białowieża Forest, a UNESCO World Heritage site described as Europe’s last remnant of primeval woodland, was by no means unfamiliar to Orpik. For her, as for the generations born and raised after the fall of the Iron Curtain, it has been associated with long, carefree childhood summers. However, nowadays, few of these nostalgic memories remain intact.

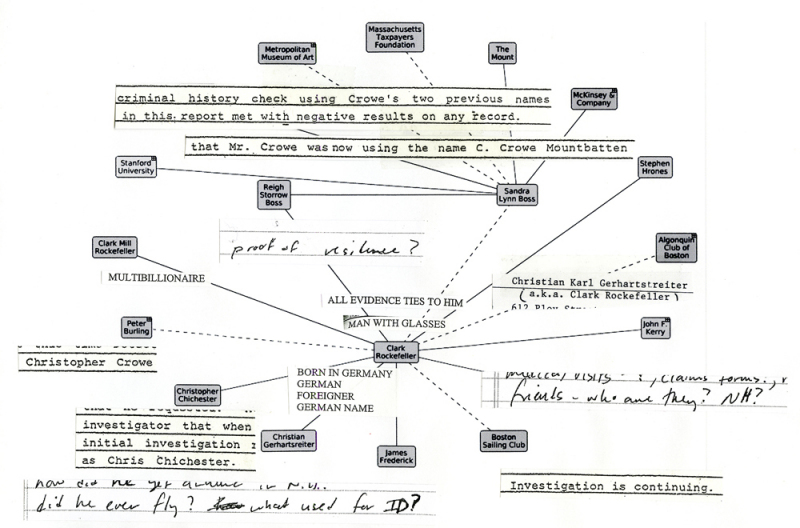

As luck would have it, a chain of tumultuous events started to unfold upon her arrival to the area, with the situation deteriorating further ever since. On 9 August 2020, the fraudulent presidential election in Belarus sparked a wave of civic protest against the Belarusian government and President Alexander Lukashenko. The brutal suppression of the demonstrations led to an exodus of members of the opposition. Belarusian dissidents found themselves stranded at border crossings between Belarus and Poland, alongside thousands of refugees from the Middle East. The Belarus–European Union humanitarian crisis in 2021 resulted in severe ill treatment and unlawful “pushbacks” of asylum seekers by border guards on both sides. The Polish government declared a state of emergency, establishing a militarised no-go zone along the border with Belarus. In January 2022, it initiated the construction of a €353 million wall aimed at deterring refugee crossings. The wall was completed in July 2022, five months after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, purportedly as an element of the “country’s fight against Russia”, in the words of Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki.

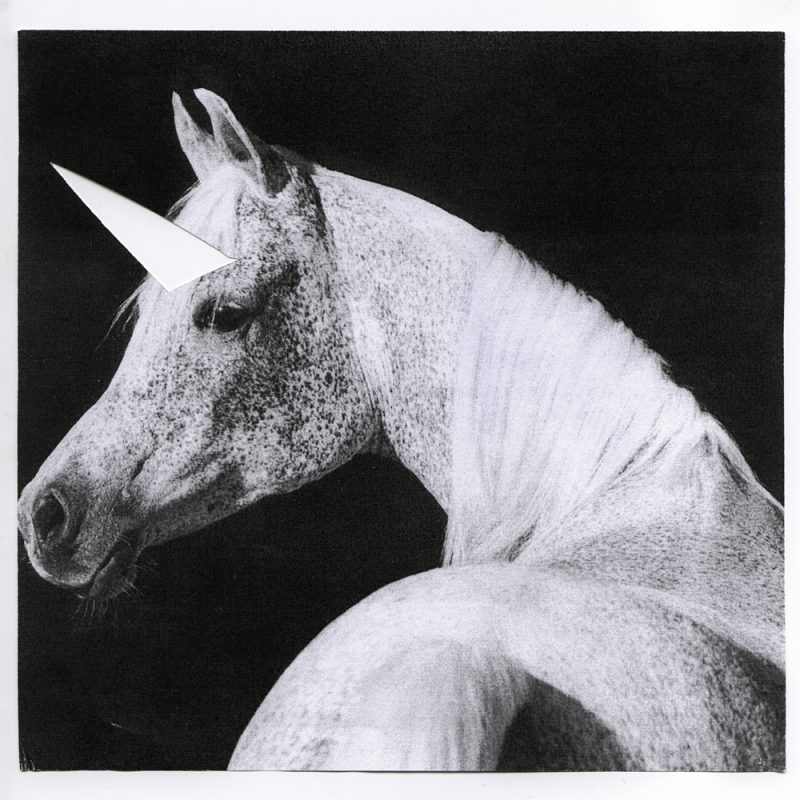

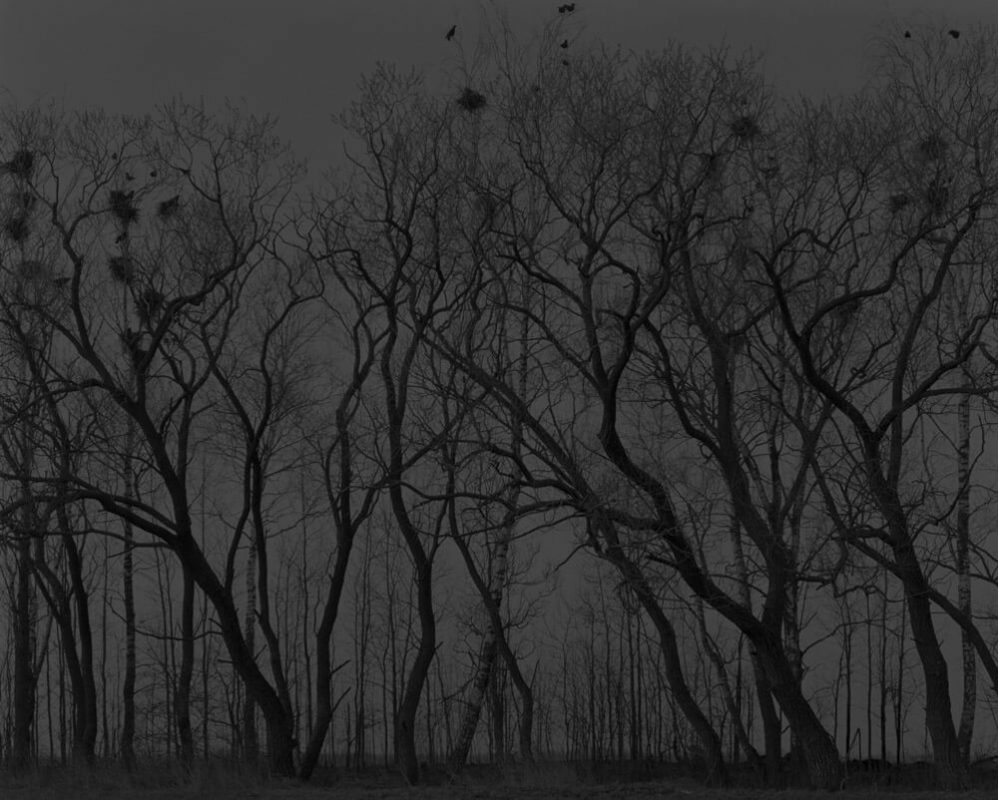

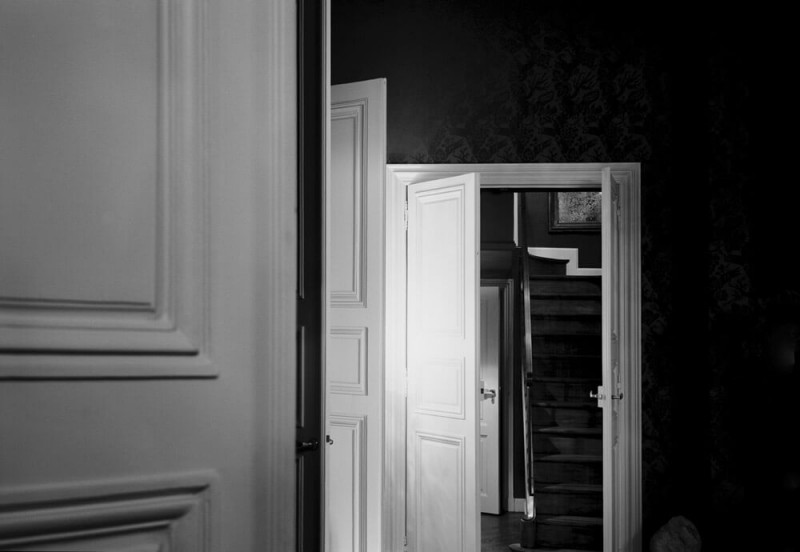

‘Place is latitudinal and longitudinal within the map of a person’s life. It is temporal and spatial, personal and political. A layered location replete with human histories and memories, place has width as well as depth’, writes Lucy Lippard in The Lure of the Local (1997). Orpik’s narrative impetus seems to acknowledge this intersubjective width and length, that is, the way in which the territory she explores is directly lived in by its inhabitants and temporal users. To start with, it articulates how a supposedly nourishing and untouched natural reserve is relegated by jurisdiction to a national boundary, and an in-between no man’s land. It bluntly exposes how the millenary trees, the brushwood and the fallen leaves of a forest become the living tissue of a ghastly past of deportations, ethnic cleansing and Cold War dystopia – a past which, up until seemingly yesterday, Europeans considered consigned to a bygone era. What once stood as a cradle of hospitality, harvest scents and folk tales is now, in the best-case scenario, a temporary shelter to those who are waiting to move forward or recover their homeland, and, in the worst, a literal graveyard for those who are left to perish.

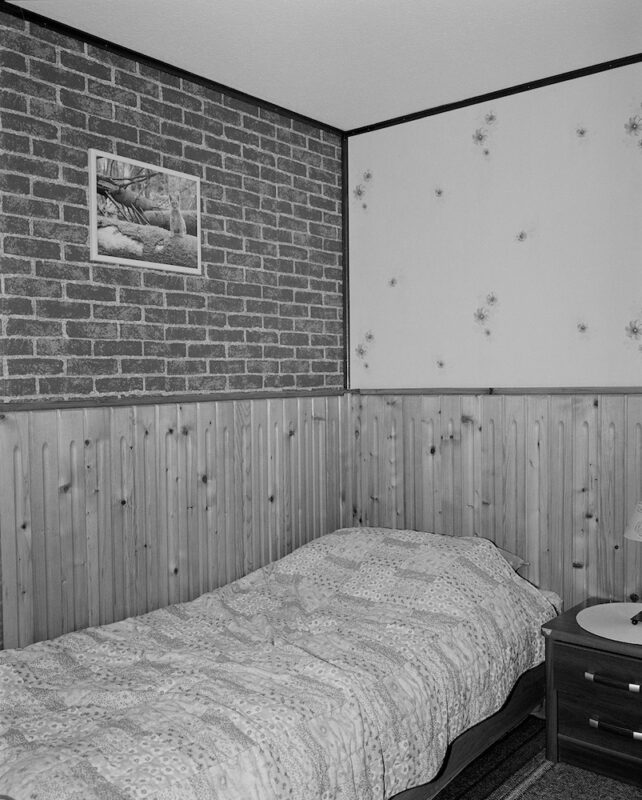

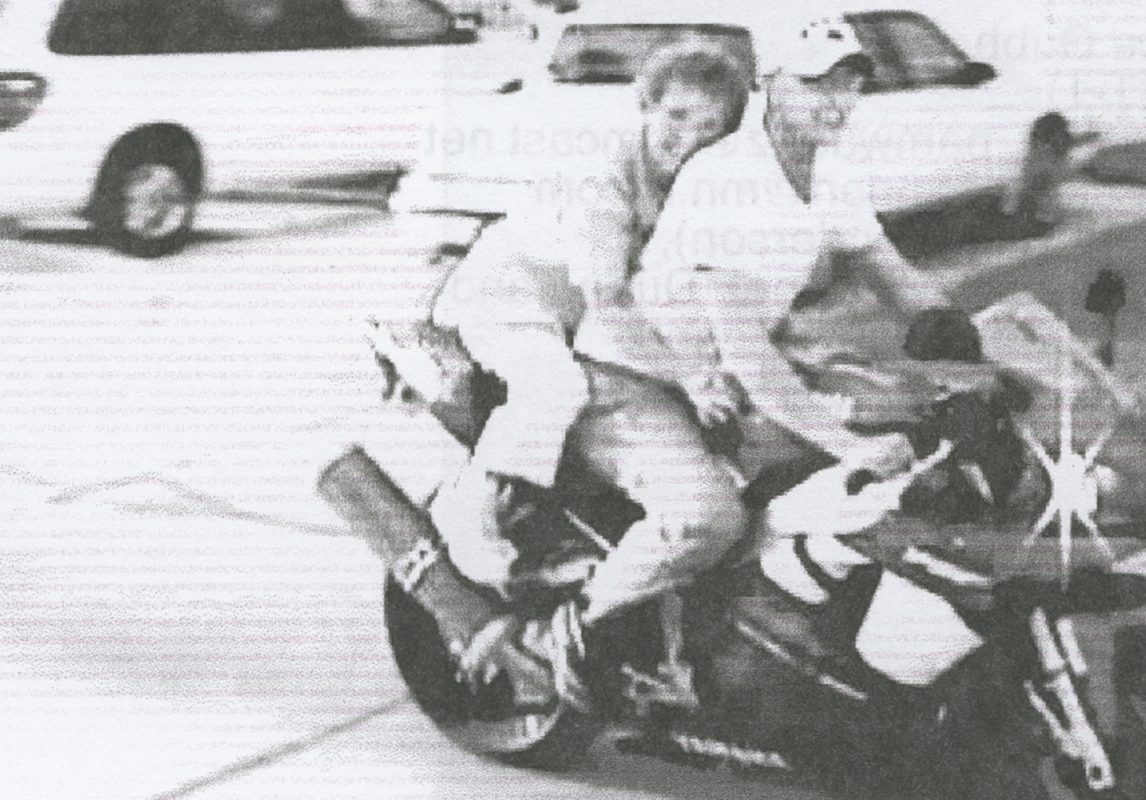

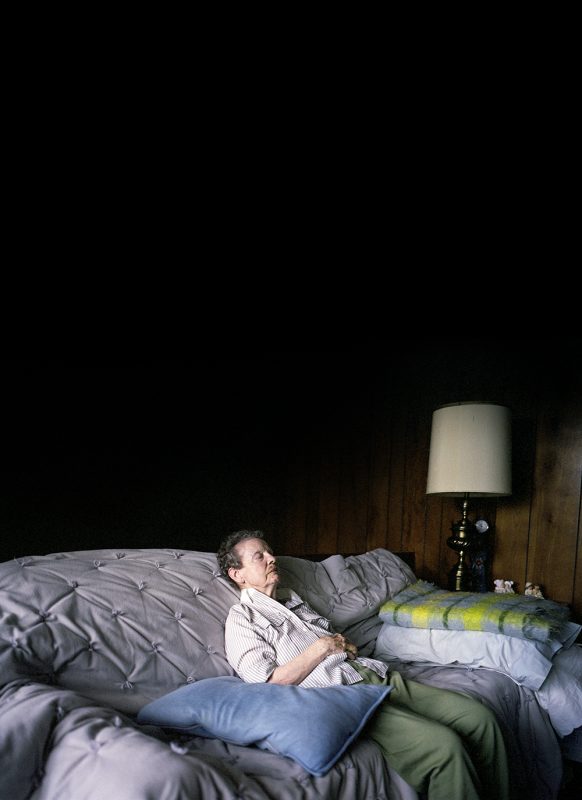

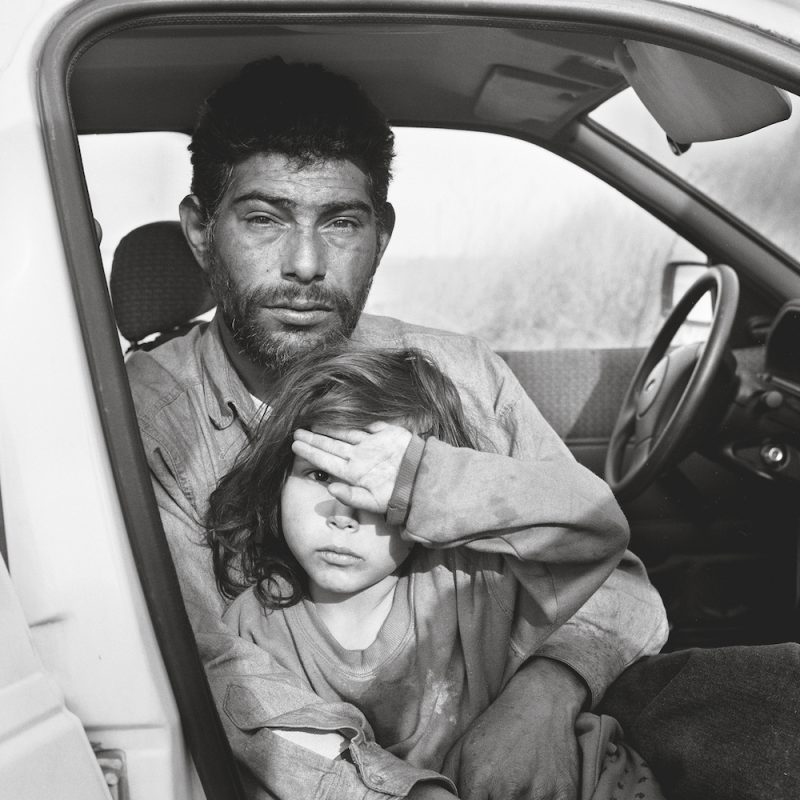

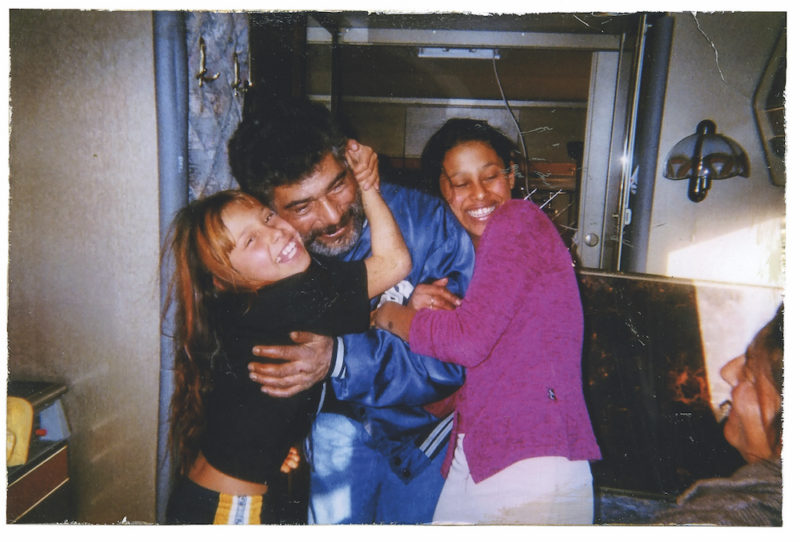

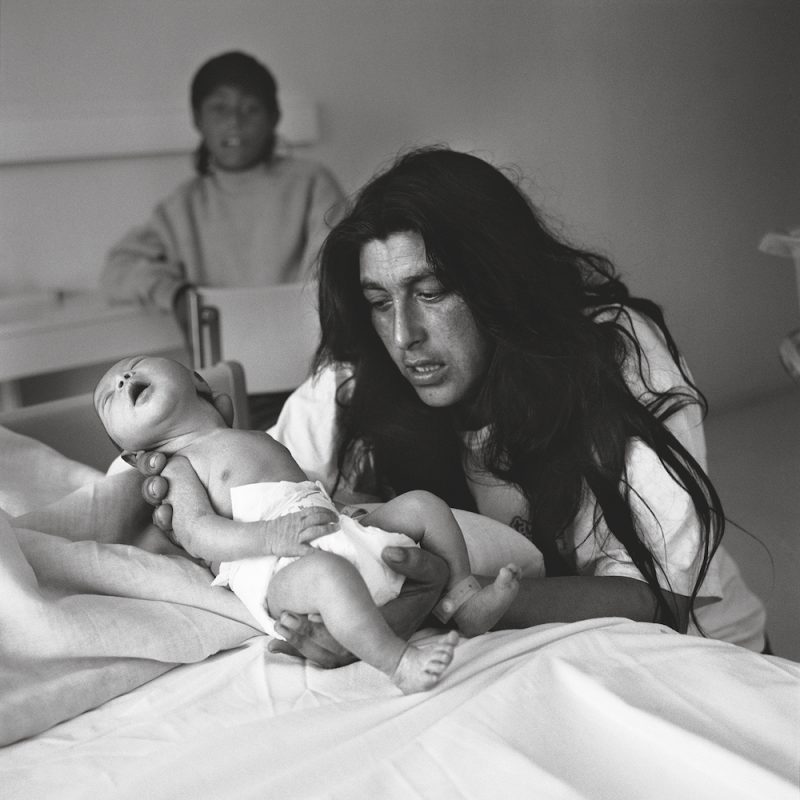

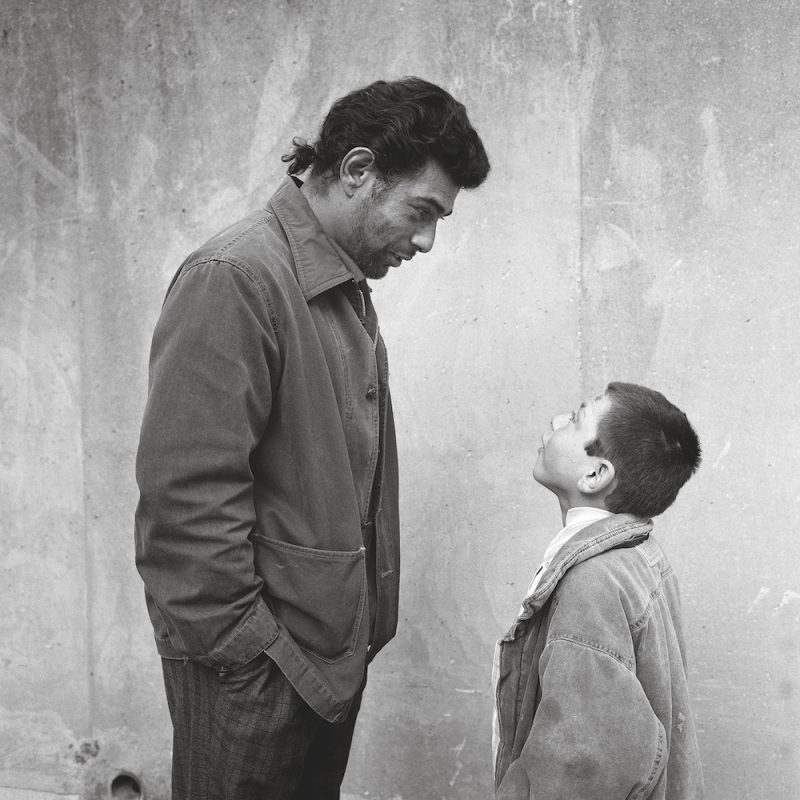

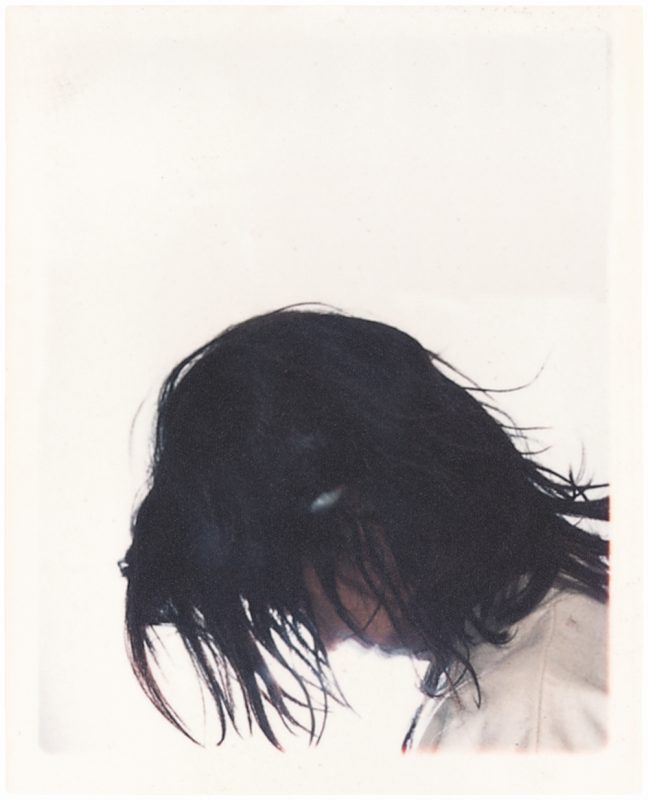

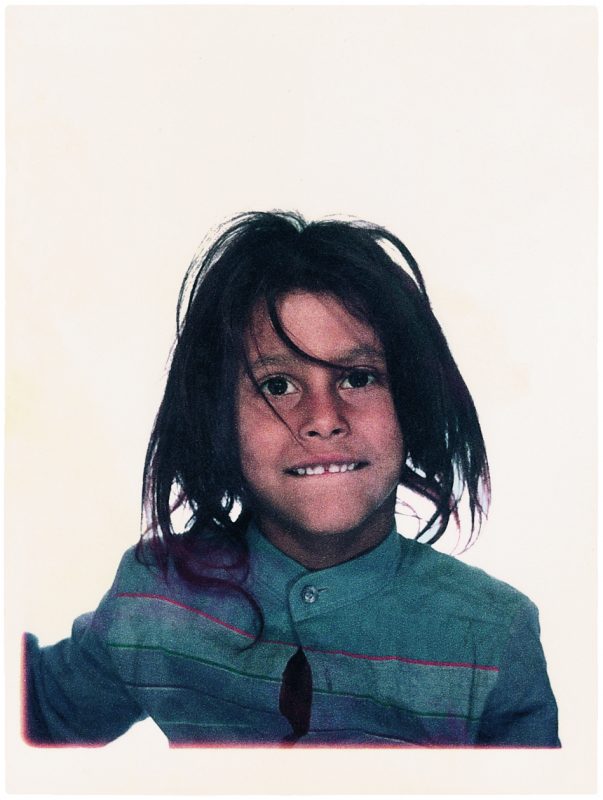

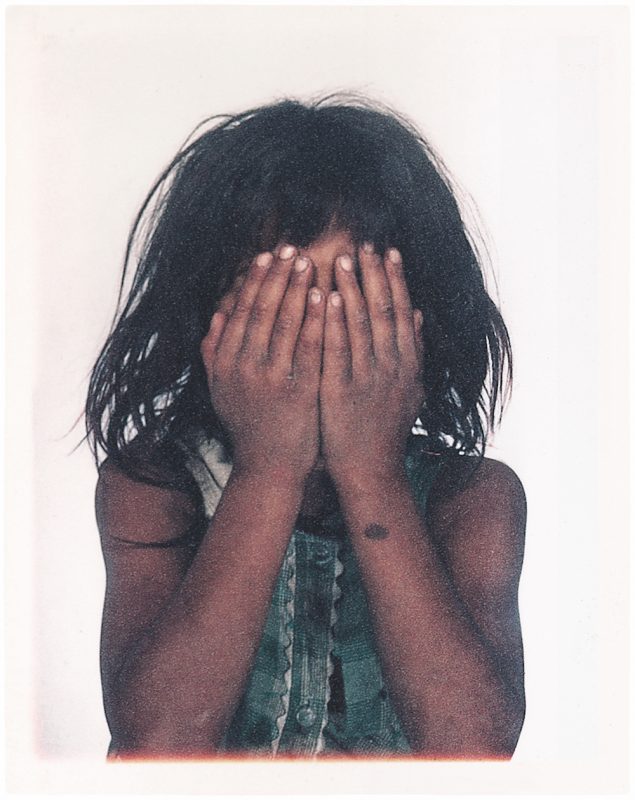

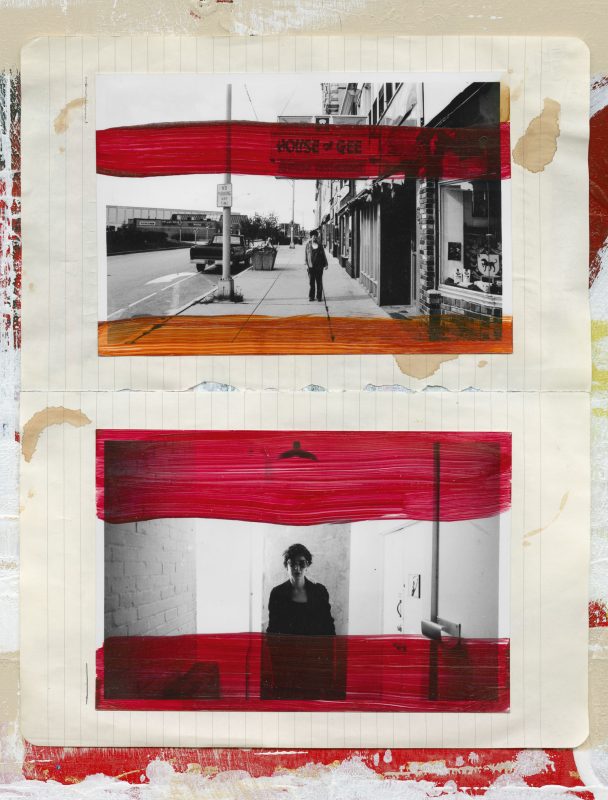

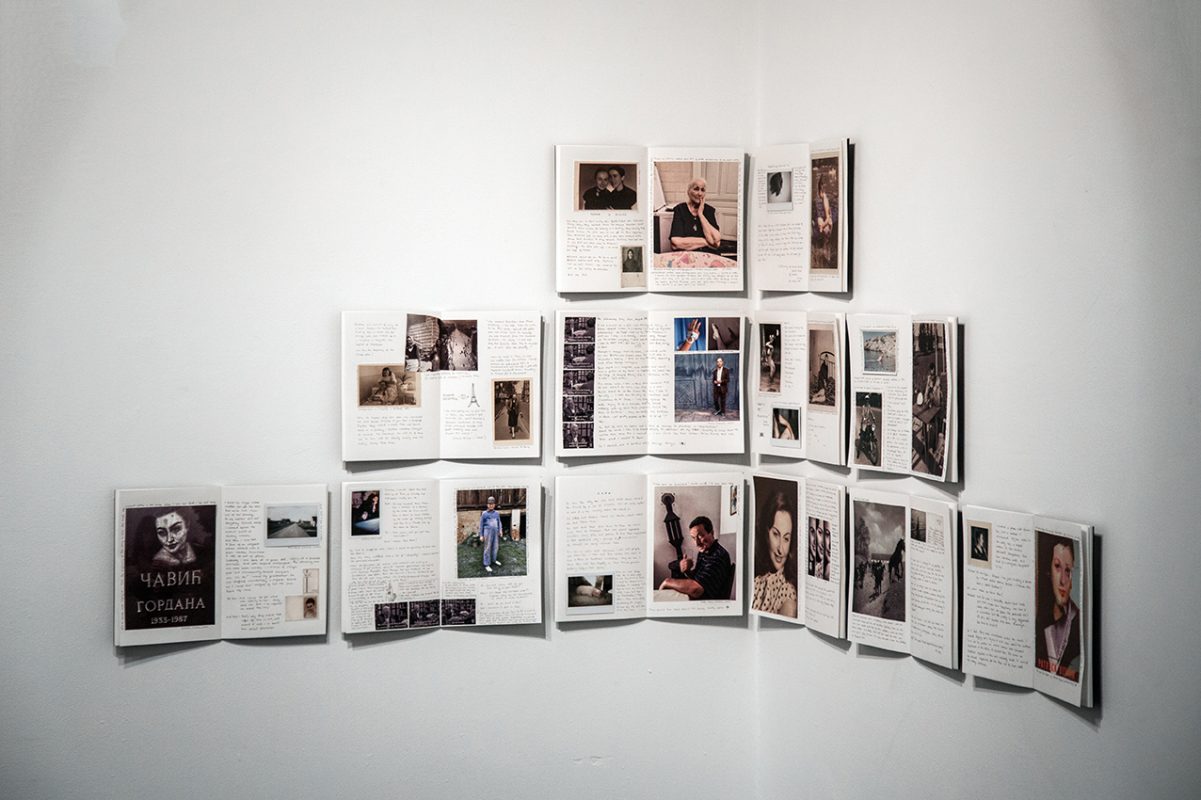

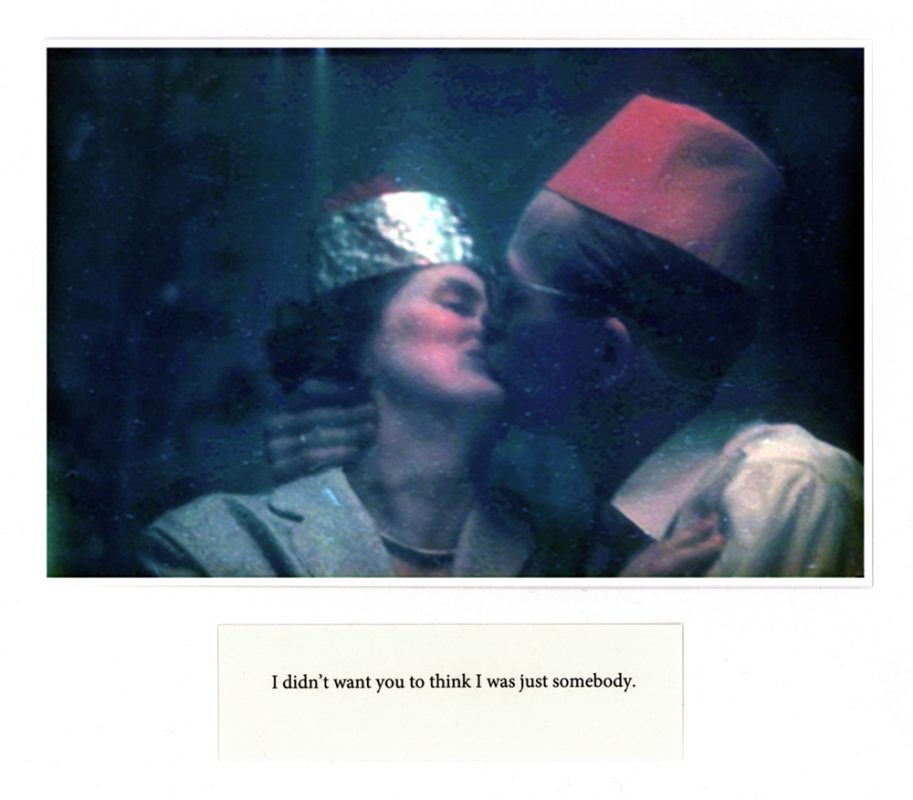

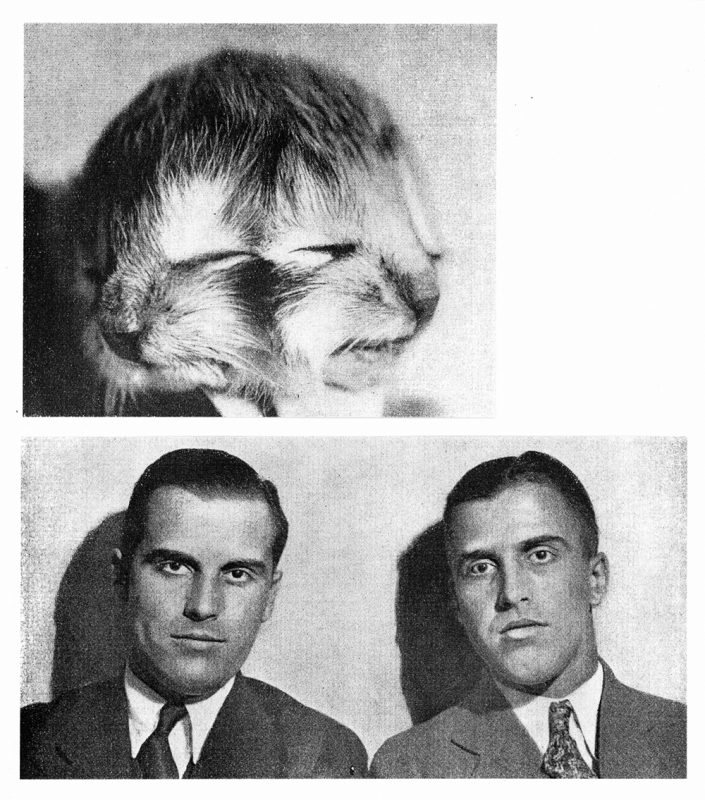

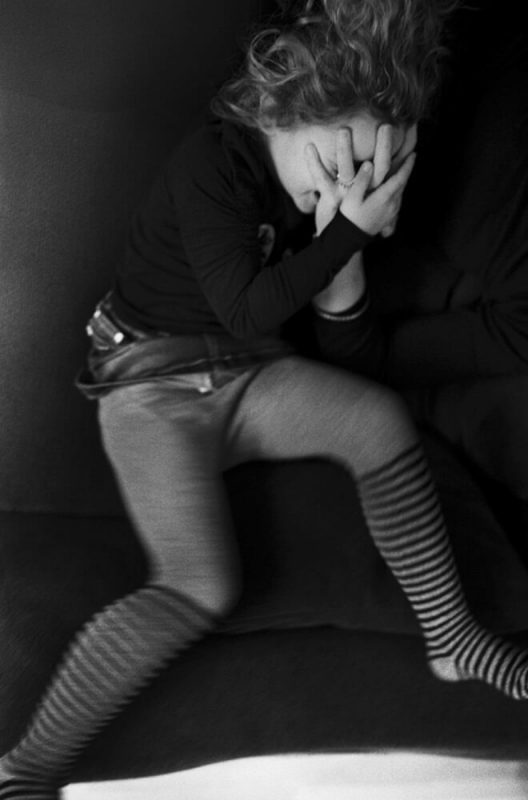

To decipher the unspoken histories of the Białowieża Forest and its neighbouring region, Orpik turns to the specific and vivid life experiences of two of the communities that currently inhabit it: asylum seekers fleeing from Belarus, and the remaining local Belarusian minority, whose ancestors endured, after the Second World War, oppression and linguistic discrimination by the Communist regimes of Poland and the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. These are the protagonists of her narrative. Their stories are told in the first person, and together with hers, they orchestrate how they wish to be represented in front of the camera: with the exception of a few isolated scenes of gatherings or people engaging with the environment around them, primarily via the landscapes, domestic spaces and objects that surround them on a daily basis, and all of this in place of straightforward portraits that could potentially expose them to the Belarusian regime.

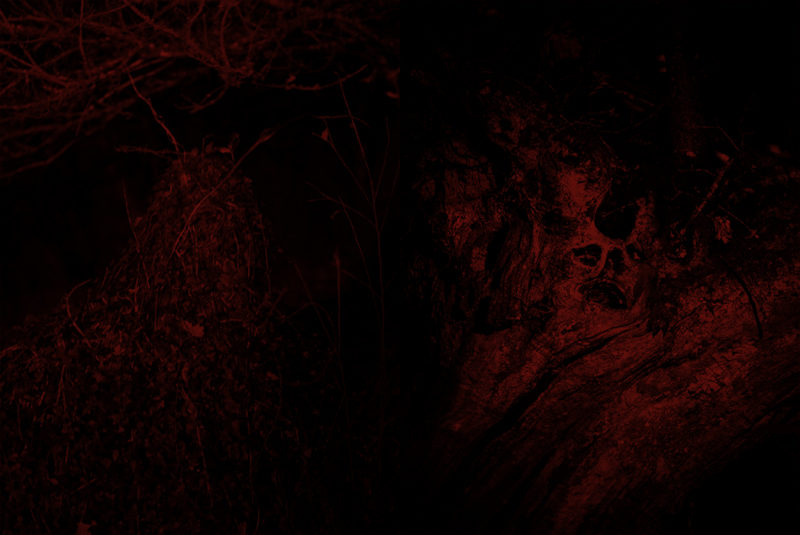

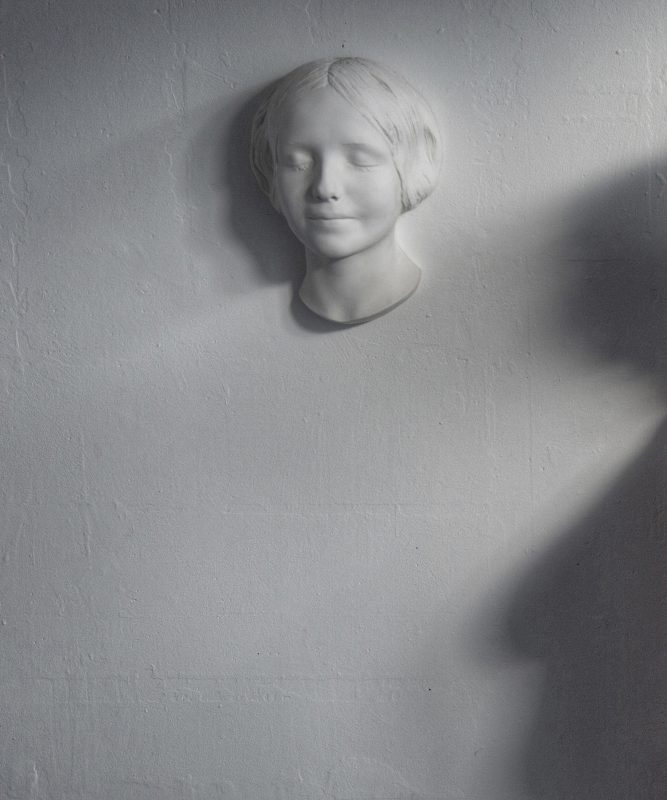

The forest as literal passage (to freedom or to exile) is the leitmotif of Stepping Out Into This Almost Empty Road. What was meant as a sentimental journey to the land of ripe apples turns into a murky psychological hinterland. The passage is invested with an encroaching greyish veil that seems to eclipse nature’s exuberant wealth and taint the soul with disorientation. There is no wanderer’s song; the wanderer does not know on which side of the border they stand.

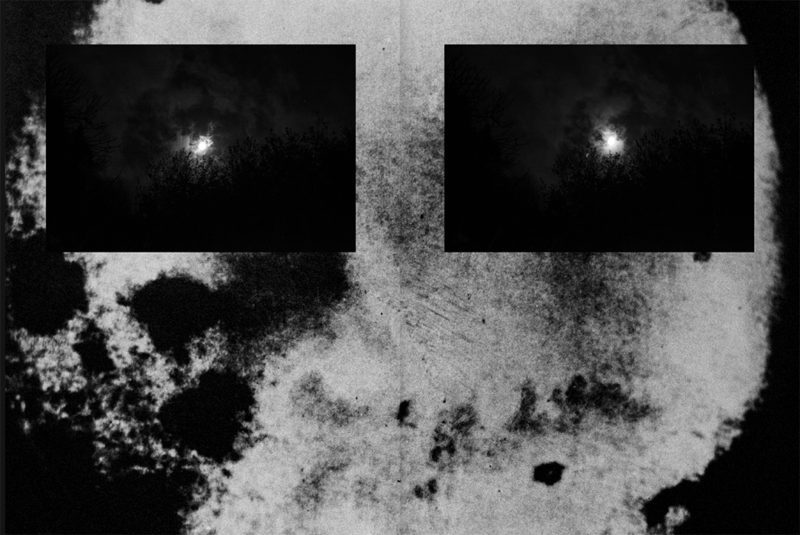

It is difficult to conceive how violent the encounter with nature can become when one is forced to undertake a clandestine route on foot that may last for days, or even weeks, through dense vegetation, in the hope of eventually making it to the other side. In her visual recreation of such an experience, Orpik takes into account her condition as an outsider, and avoids making a spectacle of it. She instead chooses to insert in her narration a series of jump-cut spreads that feature sequences of horizon shots, taken mostly from the window of her car. As if suddenly reaching a clearing, or hinting at a path or a road, these intervals condense and accentuate a gaze unfamiliar with its environment, and its frantic quest for the correct coordinates – a way through and out of this prison.

As Orpik drives around and engages in conversations with locals, her lens obsessively attends to the minutiae of interiors and exteriors where time feels stagnant and inescapable. Once more, we are given only occasional points of reference. Half-built structures, decayed surfaces and industrial ambiences appear abandoned in a precipitate manner; others seem to overcome this palpable sense of weariness and confinement, welcoming anew a domestic warmth. Wood resurfaces persistently, in tree branches, architecture, library interiors, book pages and rolls of typewriter paper. It comprehends, as a living rhizomatic organism, past uprooting next to a legacy that can sustain the promise of a solidary and peaceful coexistence in a new homeland. For the ‘universal story of migration is not only about leaving a space’, maintains Orpik. ‘It is about entering one too.’

Text is a substantial component of the book. Reminiscent of the ‘wall of language’ intersecting Michael Schmidt’s Waffenruhe (1987), it contributes to the intensification of the overarching narrative experience. Extracts from recorded conversations with 15 people – devoid, to a great extent, of specific geolocations and ethnicity terms – are edited into a collective voice. The voice in question speaks in two languages: whereas English is clearly employed for reaching out to a wider international audience, Belarusian takes on symbolic and political connotations. Its insertion is equivalent to the restitution of a language that has been consistently suppressed over decades on both sides of the border, and is currently vulnerable to extinction.

It was pivotal for Orpik and Rusznica to produce a timeless body of testimonies, beyond the dramatic twists of the ongoing political actuality in Eastern Europe. Their stark political statement calls attention to the fact that this is only the beginning – forced migration will remain on the frontlines in the face of political unrest and climate change – whilst acknowledging the ethical double standard currently applied to asylum seekers, depending on political agendas and a refugee’s place of origin.

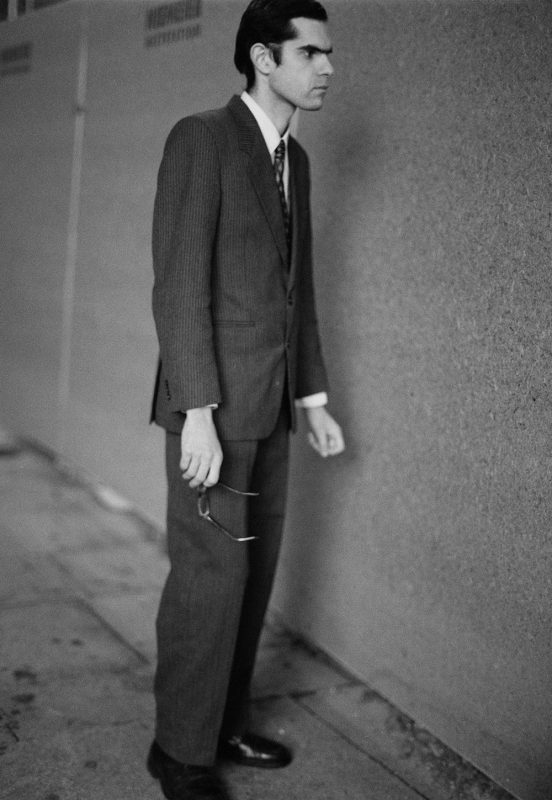

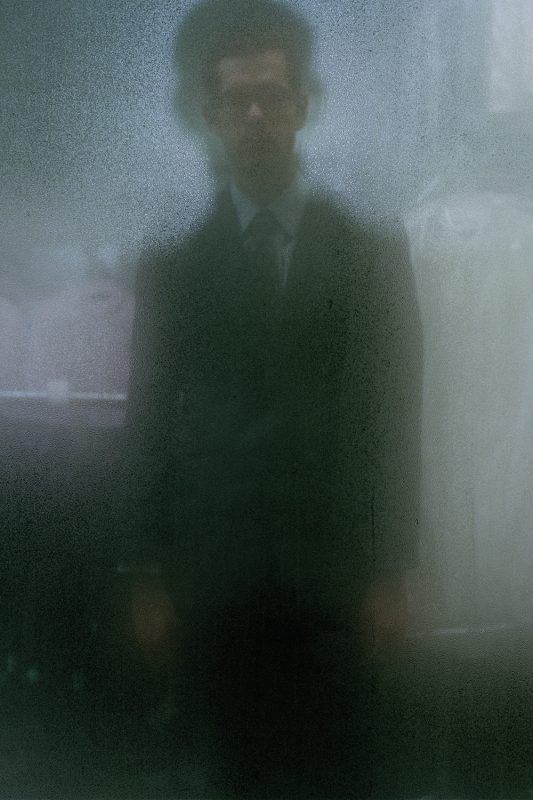

Dense and misty, the forest denies a reply to the wanderer. The forest is made to obey the law of the border and its spectral tentacles. In Stepping Out Into This Almost Empty Road, these tentacles are personified by the sequence of the orchestra conductor’s hands. The hands cut the book into two halves and establish a tempo of ambivalent gestures. And yet, in light of resurfacing division on European soil, the dim veil that enfolds them seems to slide towards the darkness of totalitarianism. The tentacles are infused with isolation and fear. Fear, above all – for even when the border and the regime eventually dissolve, the fear will not. From the Evros River in Greece to Spain’s Melilla border fence in North Africa to the militarised Polish border zone, the natural landscape – now tamed as a claustrophobic confined territory, a no man’s “zone”, or what Giorgio Agamben calls the biopolitical paradigm of the ‘camp’ – seems to offer no way through. ♦

All images courtesy the artist © Monika Orpik

Stepping Out Into This Almost Empty Road is published by Ośrodek Postaw Twórczych (OPT).

—

Natasha Christia is an unaffiliated curator, writer and educator based in Barcelona. She holds a BA in archaeology and art history from the National Kapodistrian University of Athens, an MA in modern art and film from the University of Essex and a postgraduate diploma in publishing from the University of Barcelona. Ηer curatorial research and writings focus on the way photography, archive, film and the photobook interact with the 21st century artistic avant-garde.