Photo London 2023

Top five fair highlights

Selected by Alessandro Merola

With 125 galleries from over 50 cities, the eighth edition of Photo London proves that amidst the emergence of ‘disruptive’ new technologies, the miracle of the darkroom is as alive today as it has ever been. Here are five standout displays from the UK’s largest photography fair – selected by 1000 Words Assistant Editor, Alessandro Merola.

Prince Gyasi steals the show at the booth of Paris-based Maât Gallery, which has newly-established a small but exciting roster of artists with close ties to west Africa. A bold and fresh talent who shot to fame with his inspiring iPhone shots offering alternative visions of daily life in an around Accra, Gyasi is staging brilliant new works here which will bounce your senses like a pinball machine. Enlivened by an Afropop-dubbed palette – packed with colours as vibrant as if squeezed directly out of a paint tube – these exuberant, dreamlike utopias channel Gyasi’s synaesthetic sensibility, in turn prizing perception over objectivity. Making a memorable appearance is a paper plane-hurling fisherman whose image appears unburdened by stereotypical Western visual scripts of “Africa”. As for the other protagonists, they are equipped with cardboard wings, fish and giant eggs. Gyasi utilises everyday symbols that border on the mundane, and edits them into the sublime.

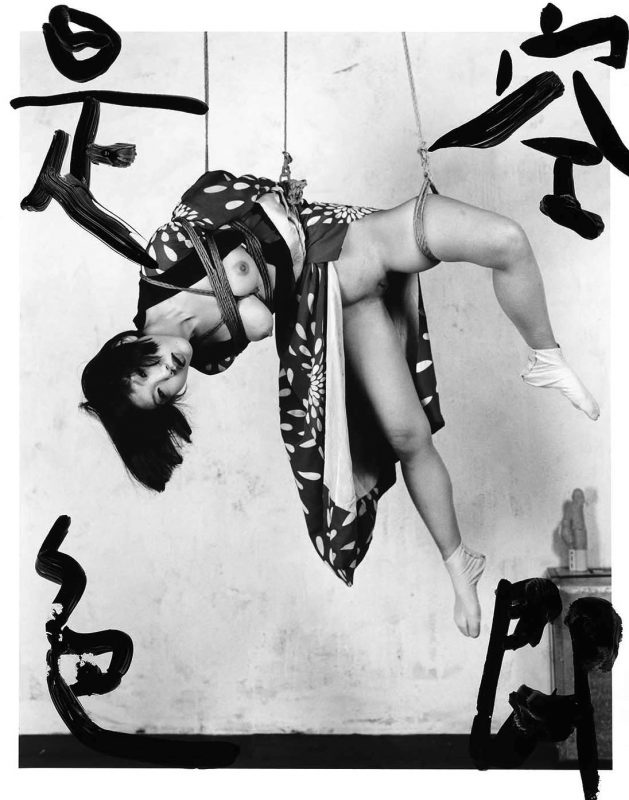

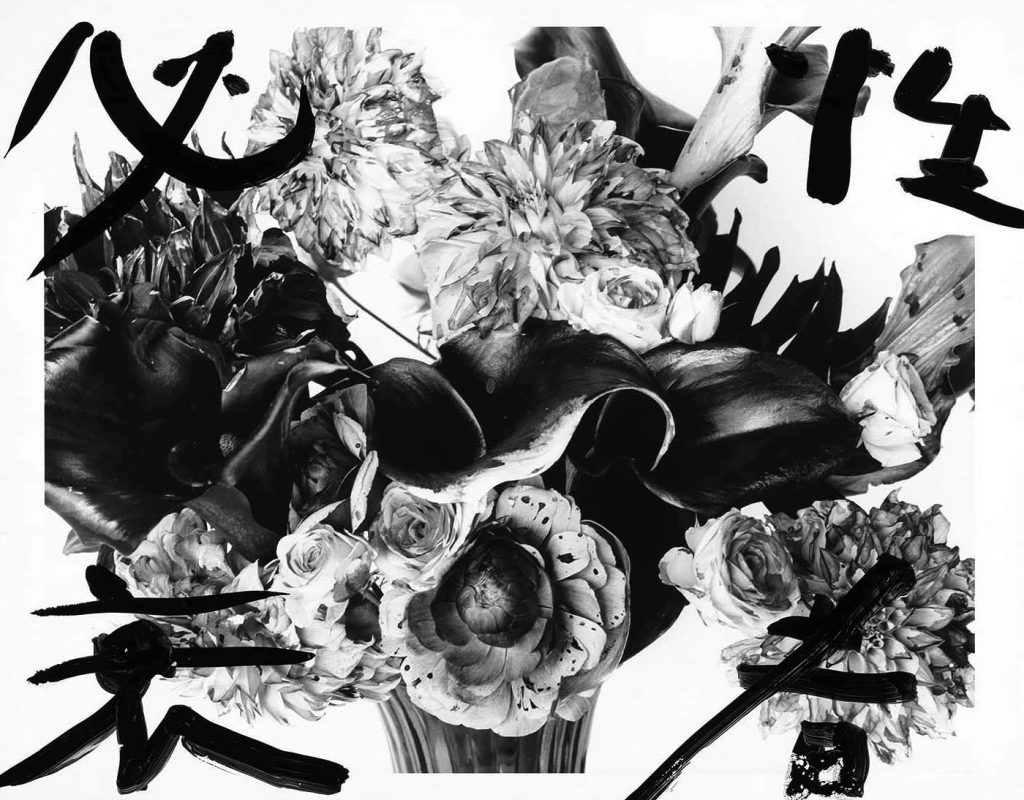

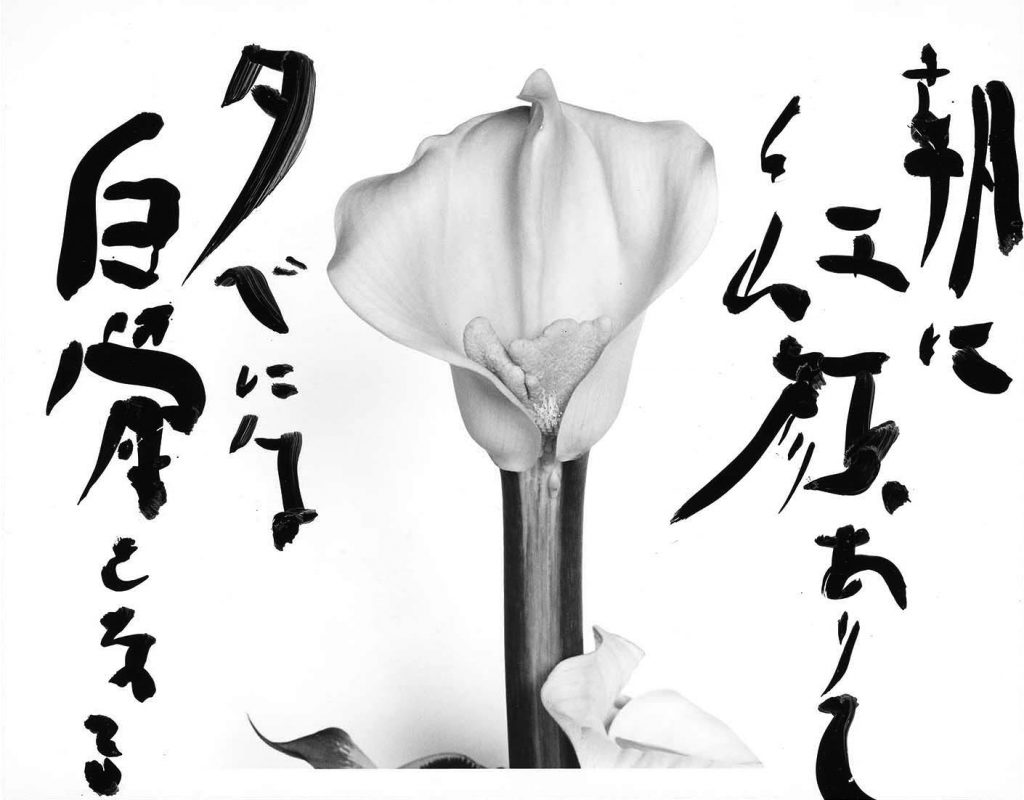

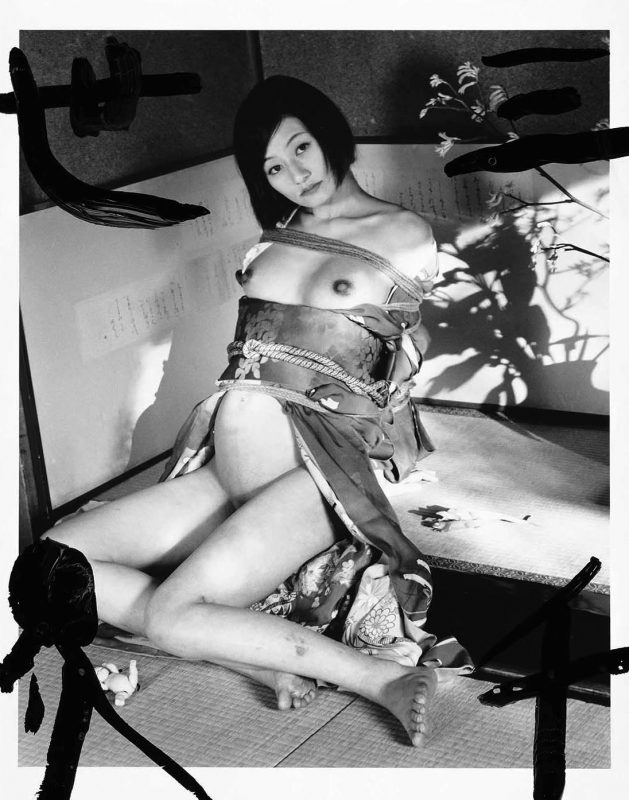

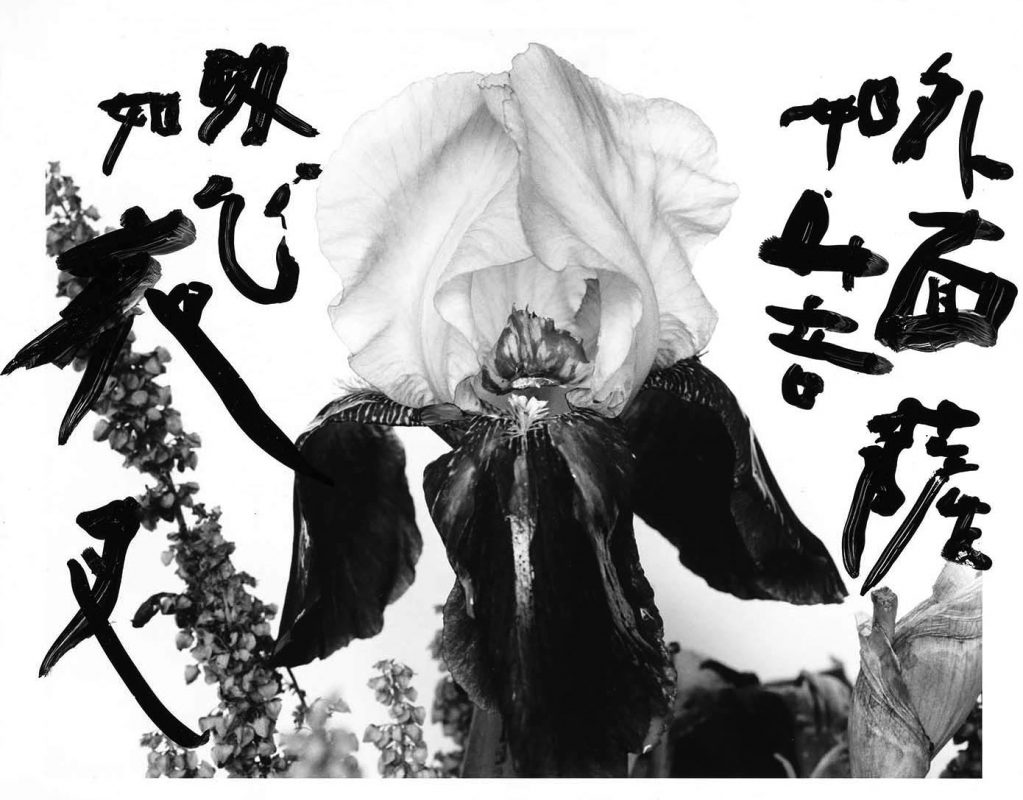

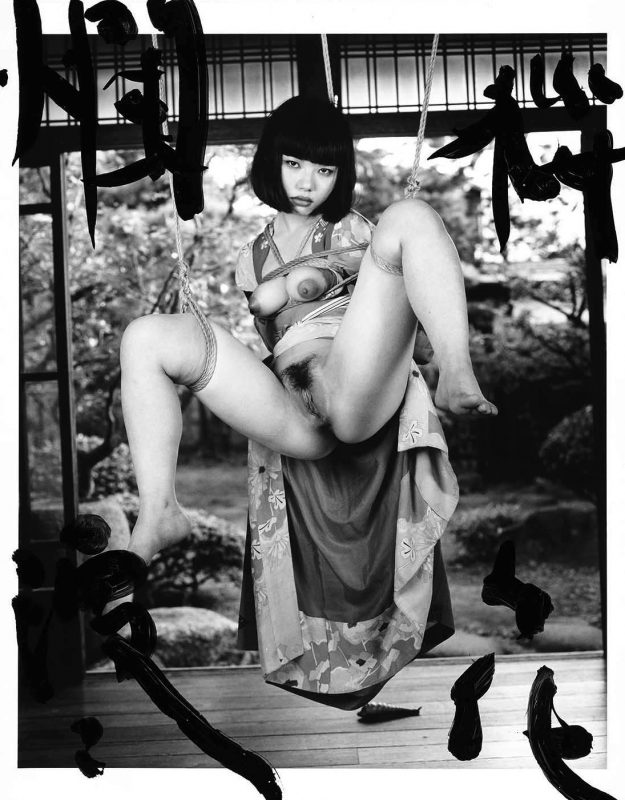

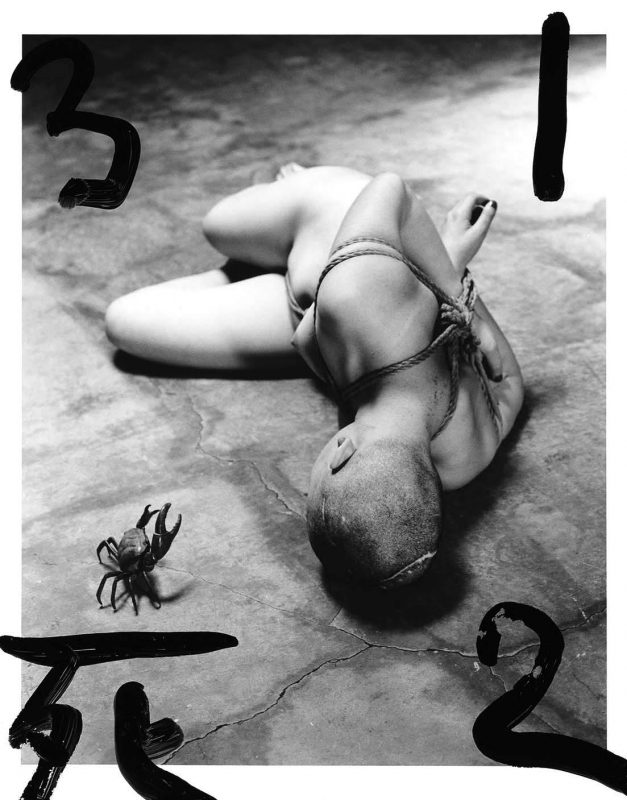

2. Sakiko Nomura and Chieko Shiraishi

Galerie Écho 119

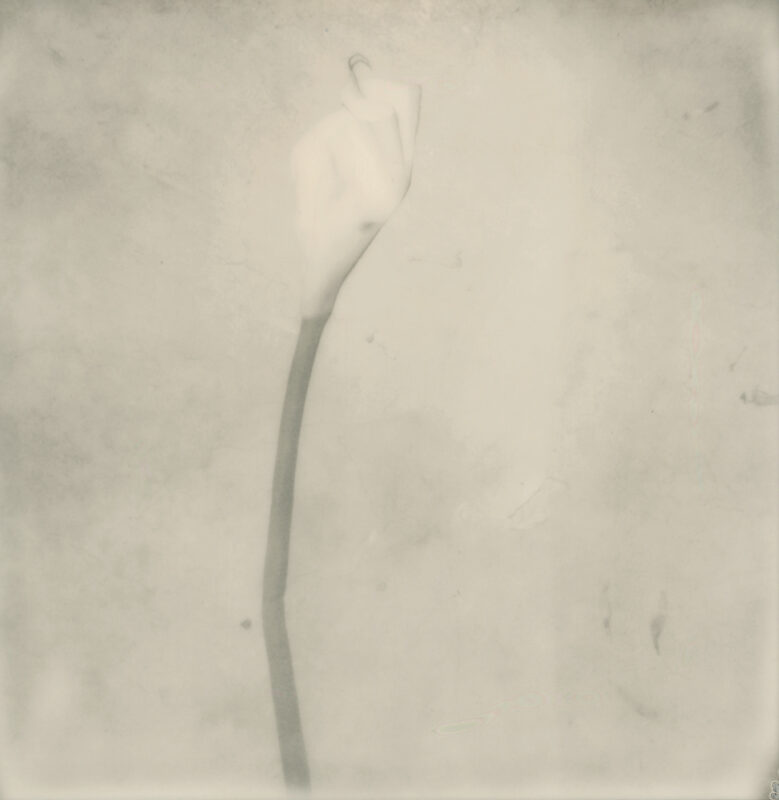

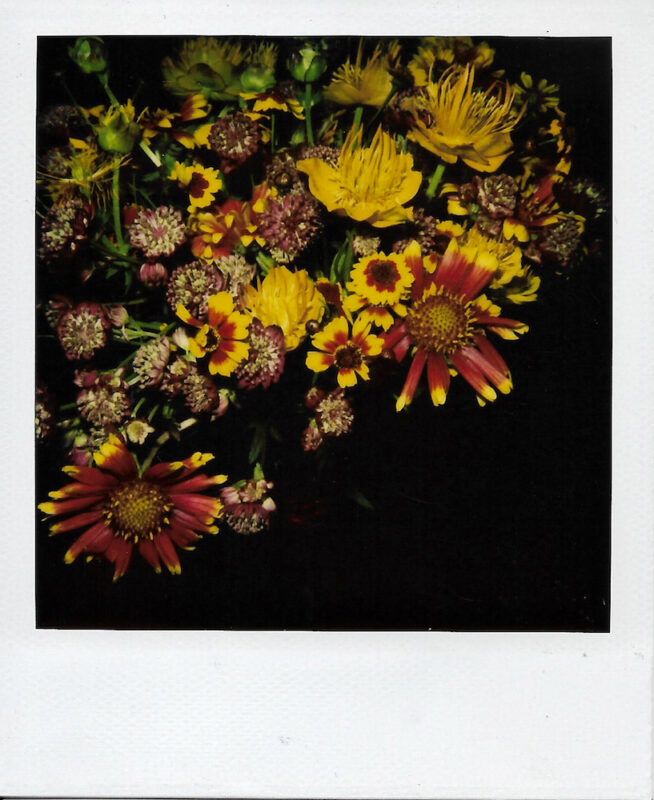

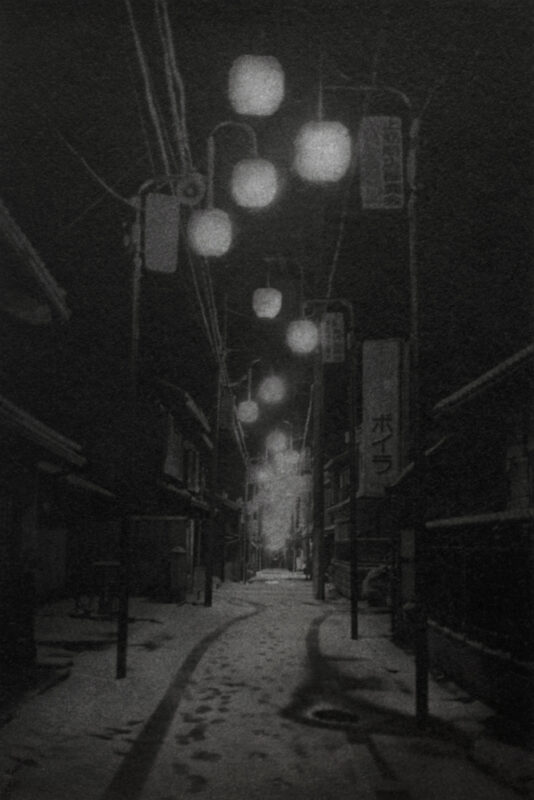

Never failing to disappoint is the Discovery section, where Galerie Écho 119 is amongst the many young galleries making a strong first impression. Unmissable are the Polaroid triptychs of Sakiko Nomura, which are characterised by a soft, female gaze. Curiously, in the early 1990s, she served as the (only ever) assistant of Nobuyoshi Araki, who is also represented with a selection of Polaroids. But it is Chieko Shiraishi’s spine-chillingly beautiful, moonlit prints which make this booth a standout. Splayed across the wall in a way that makes one wonder where each begins and ends, they are products of zokin-gake, an old Japanese retouching technique involving the wiping of a rag. By way of Shiraishi’s conjuration of an intricate web of gradual transformations – one which evokes the twin figures of experience and emptiness with nuanced sensitivity – subject becomes subservient to content. The subject may be a mass of fog that swallows a spiralling staircase, or the footprints that creep up a desolate, snow-clad alley. The content is Shiraishi’s response to what she saw; shorthand notes from her spirit.

3. Jack Davison, Photographic Etchings

Cob Gallery

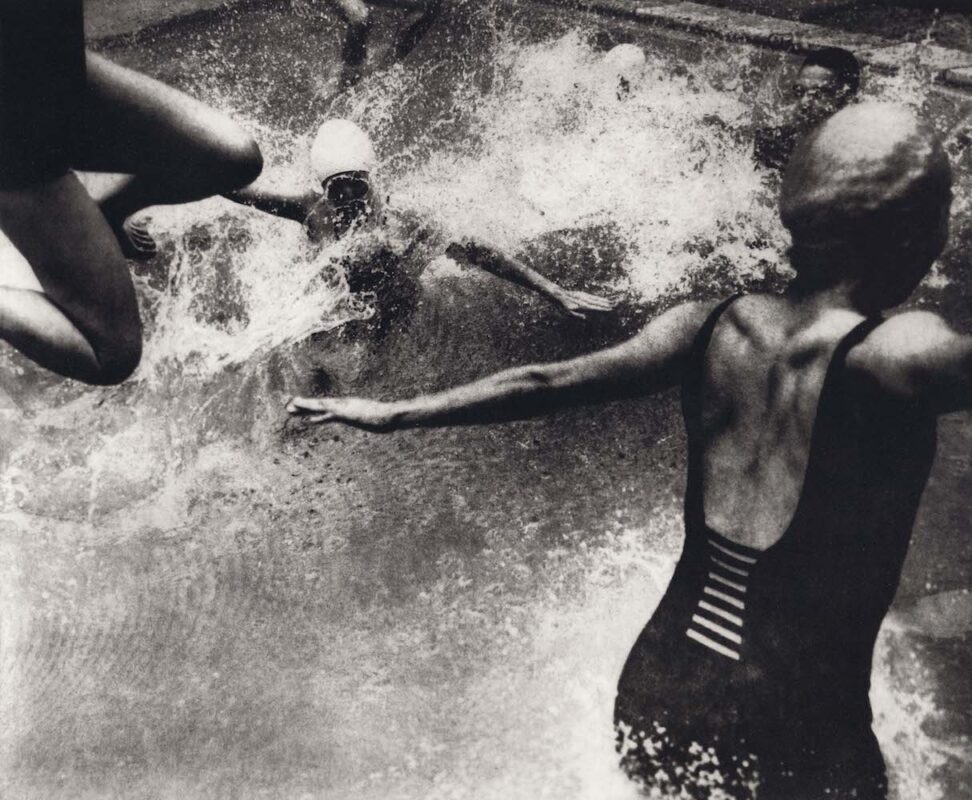

Photography-as-magic – as uncloaking the image through rag-rubbing, Polaroid-shaking or otherwise – is also evidenced in a dazzling presentation by London’s Cob Gallery. Those who were impressed by Jack Davison’s Photographic Etchings exhibition last year – and left wanting to see more from the artist’s archive – will welcome this latest outing. The booth compiles an absorbing selection of Davison’s black-and-whites – previous photogravures, new works as well as unseen artist proofs – that, together, relinquish such immersive drama. They are tactile things, suspended in frames like fragments wherein truth is always out of reach. Any of photography’s indexical factualness that remains in these introspective gravures lingers only as a vague aura of the technology which aided in their production. After all, although they are derived from photographs, they appear as distant cousins of the source image. For Davison, the camera is a tool, and, if the photograph endures, it is merely as a material memory of the process, squarely situated within the tradition of etching.

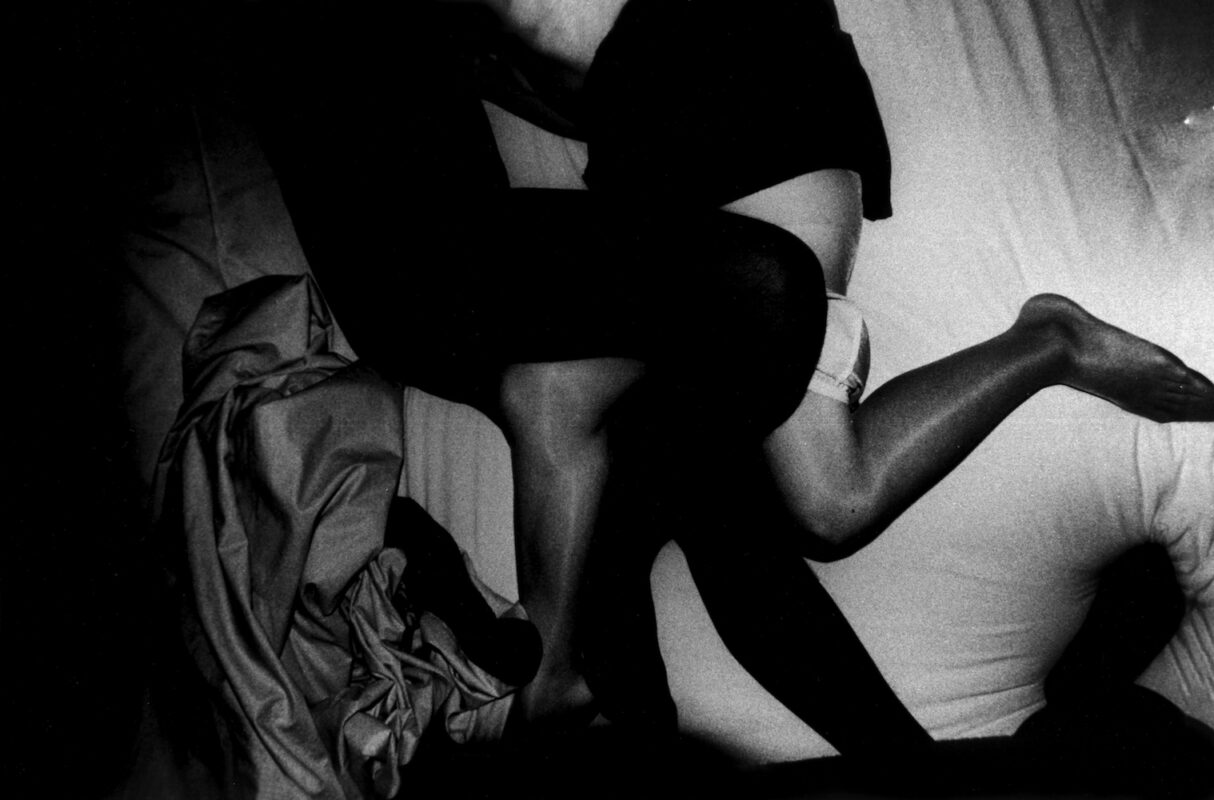

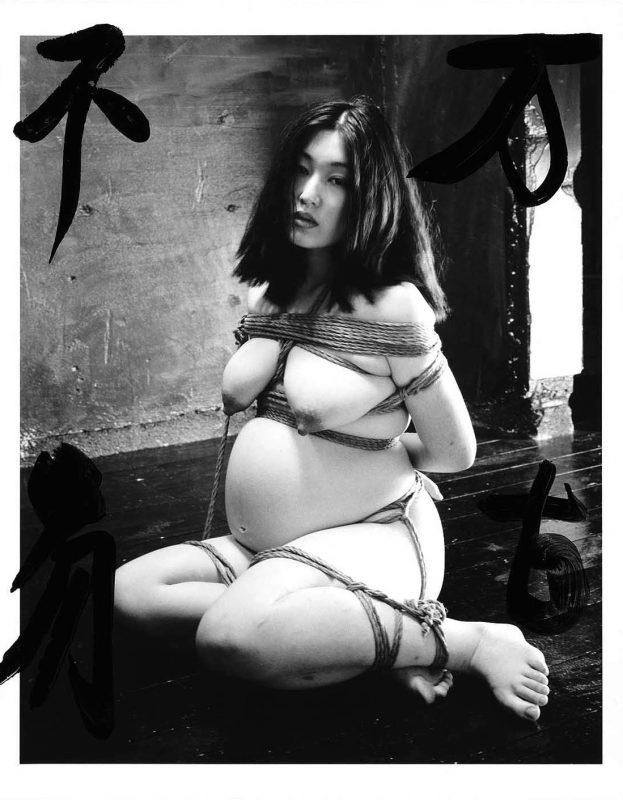

4. Hideka Tonomura, mama love

Zen Foto Gallery

Since the families of Nan and Mann, respectively, redefined the stakes for documenting one’s own tribe, one particularly dramatic case of a photographer probing the ambiguous relationship between the camera and intimacy is undoubtedly Hideka Tonomura. Arranged alter-like on a wall at Zen Foto Gallery – one of several galleries at this edition hailing from Asia – mama love unveils a vital and cathartic threesome: the revenge of the artist’s mother against her tyrannical husband; a rebellion against the ordeal she endured for years. Whilst Tonomura becomes less a witness and more an accomplice in this adulterous affair, by “burning out” the male protagonist in the darkroom, the artist seems to suggest that he, if anything, gets in the way. Tonomura’s series is not deliberately provocative, nor does it revel in sexual voyeurism. Instead, it is the patient record of a conversation between a mother and daughter, and a rediscovery of their love for each other. It’s both radical and radiant.

5. Chris Killip and Graham Smith

Augusta Edwards Fine Art

Off the back of 20/20, last year’s very special joint presentation at Augusta Edwards Fine Art, it is satisfying to see the two great British photographers Chris Killip and Graham Smith side-by-side once more. The latter is lesser known, of course, but there is a strong case to be made that the two really ought to be mentioned in the same breath for their exceptional, community-focused documents of people living in the North East’s edges during the Thatcher years. Where Smith very much belongs to Middlesbrough, the industrial town in which he was born and raised, Killip was an outsider determined to earn the trust of Tyneside’s working-class. Nevertheless, their respective works lack any critical distance from their subjects and are both borne from a similar time-intensive, personal involvement. There is graft and there is grace in these two peerless photographers. Smith’s shot of the historic Forty Foot Road is powerful, sobering and formally beautiful, whilst humming as a scene of life is Killip’s portrayal of Helen – upside down and limbs akimbo – who stars elsewhere in his seminal chronicle of Lynemouth’s sea-coalers. Within this little facet of social history, one finds humanity in spades. ♦

Photo London runs at Somerset House until 14 May 2023.

—

Alessandro Merola is Assistant Editor at 1000 Words.

Images:

1-Prince Gyasi, Airbon II (2023). © Prince Gyasi. Courtesy Maât Gallery.

2-Prince Gyasi, Limitless (2023). © Prince Gyasi. Courtesy Maât Gallery.

3-Sakiko Nomura, Untitled (date unknown). © Sakiko Nomura. Courtesy Galerie Écho 119.

4-Nobuyoshi Araki, Untitled (c. 1990s). © Nobuyoshi Araki. Courtesy Galerie Écho 119.

5-Chieko Shiraishi, Notsuke, Hokkaido (2012). © Chieko Shiraishi. Courtesy Galerie Écho 119.

6-Jack Davison, Untitled (2023). © Jack Davison. Courtesy Cob Gallery.

7-Jack Davison, Untitled AP2 (2022). © Jack Davison. Courtesy Cob Gallery.

8-Jack Davison, Untitled (2023). © Jack Davison. Courtesy Cob Gallery.

9>10-Hideka Tonomura, mama love (2008). © Hideka Tonomura. Courtesy Zen Foto Gallery.

11-Graham Smith, The Forty Foot Road in the Old Iron District of Middlesbrough (1978–79). © Graham Smith. Courtesy Augusta Edwards Fine Art.

12-Chris Killip, The Laidler family, Lynemouth, Northumberland (1983). © Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos. Courtesy Augusta Edwards Fine Art.