Paddy Summerfield

Empty Days

Book review by Gerry Badger

Empty Days is Paddy Summerfield’s third book for Dewi Lewis, but the first I can review, because I wrote texts in the other two. So this is hardly an impartial view, I have known Paddy and admired his work for decades. I am pleased, however, that the books have begun to bring him the wider recognition he deserves after being one of British photography’s hidden gems for so many years.

One reason I think, why his light has been hidden under a bushel – apart from a natural disinclination to push himself outside Oxford – is because his work is difficult to classify. He is neither an obvious documentary photographer nor an art photographer; neither surrealist nor diarist, but a combination of all these things. In three pages of notes he once sent to me, he refers to himself a documentary photographer, but one who, in Empty Days, ‘weaves the images into a personal document, a subjective story where everything is tragic, but there is also hope.’

He is no doubt a singular photographer. Each of his books is different, yet linked by an absolutely distinct voice. One might say that it’s an odd voice, and it certainly is, although I do not mean that in any pejorative sense – quite the opposite. I have often thought that Paddy Summerfield was a kind of British Ralph Gibson, but much less calculating or mannered. His ‘oddness’ is the real deal.

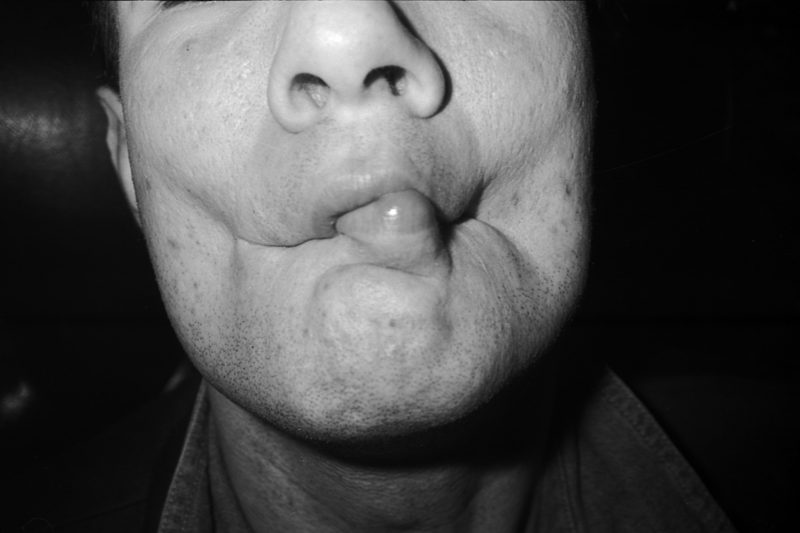

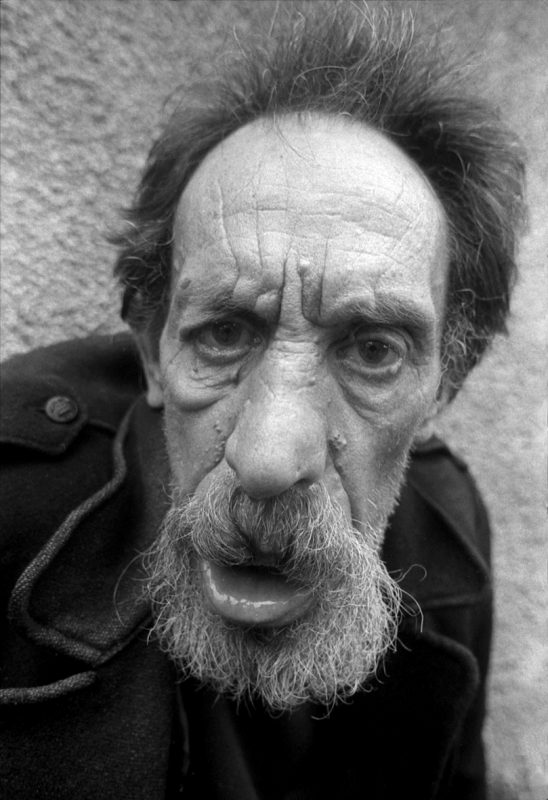

This is clear, I think, in Empty Days, which by Summerfield’s own admission explores the darker side of his psyche, encompassing religion, depression, sex, alienation, and Rock ‘n’ Roll (in the shape of his beloved Beatles) but you hardly need to know him to get a clear sense of this. The book explores aspects of the human condition, of a troubled soul, in a beautiful series of always surprising and quirky images, chosen from fifty years of work. It can be regarded therefore as an autobiography, or a fragment of an autobiography, because all Summerfield’s work is essentially biographical – as, essentially, is most photography – and the other two books, Mother and Father (2014) and The Oxford Pictures (2016), which are quite different from this new work, show other sides of his personality.

As I have intimated, his aim in Empty Days is quite clear: ‘I show the sadness in the world – I don’t know if I show it to push it away or hold on to it.’ If that sounds excessively gloomy, remember that this is a work of photo-literature, not a stream-of consciousness confession to a therapist. These are photographs, woven into a loose, suggestive narrative, and both their formal and symbolic qualities are there to be enjoyed. The imagery covers a number of photographic genres, from landscape to portrait to nudes to still-lives to Paddy’s inimitable ‘street photography’, which is usually done on a beach, and unlike the work in the recent show of British beach photography at the National Maritime Museum, London, which he would have graced, generally features single figures, which only shows he doesn’t go to the beach on Bank Holidays. The single figure shot is a striking feature of the book. Frequently, although he gets close, their facial features are indistinct, turned away from the camera or photographer’s gaze, so the sense of sadness and alienation is underscored. Indeed, Summerfield may well be one of the best photographers of loneliness around.

Summerfield also tackles religion, though whether he sees this as solace or a cause of our modern ills, is, like much in his work, left tantalisingly open to question. ‘In the book,’ he writes, ‘beneath the surface there’s a strand of spirituality implied, a layer of religious symbolism.’ It’s hardly beneath the surface. We begin with a cross tattooed on an arm, and progress through a stature of Christ, a child lying in a crucified position to another cross in a cemetery. His attitude to sex is also far from clear. There are a number of sexualised images, nudes or semi-nudes, but again, it would seem that, in a manner similar to religion, sex leads only to melancholy and disappointment rather than ecstasy or fulfilment. These figures seem to find little sense of connection in what should be the most connective act of all.

This all sounds like an incessant catalogue of gloom, but there are many consolations in Empty Days. Firstly, many photographers make diaristic books, but much of them are superficial, narcissistic views showing little self-awareness or questioning – neither exploring an inner life nor the potentialities of the camera. If Empty Days is diaristic or biographical, it is not in a me, me, me onanism, and one gets the impression that, although the story is important, so too was the making of the images. Summerfield gets his own joy and consolation from making striking and distinct photographs, and so can we. It is so good to see a photographer concerned with photographic picture-making in the basic sense. Engaging his eyes with the world, and making elegant, simple photographs that, when put together using a keen brain, are not as simple as they look. Empty Days is not so much documentary or diaristic or whatever but a visual poem of great beauty and useful meaning.

I end with a musical analogy (not the Beatles I’m afraid). Ludwig Van Beethoven had an extremely difficult life, his renowned deafness being only one aspect. He was in constant pain and was increasingly isolated towards the end of his life when – completely deaf – he composed his late string quartets. In these searching, elegiac works, there is every emotion, from bubbling joy to profound sadness, except one – there is never despair. While hardly seeking to equate him with Beethoven – John Lennon is enough – the same could be said about Paddy Summerfield. He makes sure to end Empty Days with two images of hope – a bird wheeling and dancing in the sky. As I have said, this is not a wholly impartial review, but this has to be a strong contender already for one of the best photographic books of the year. ♦

All images courtesy of Dewi Lewis Publishing. © Paddy Summerfield

—

Gerry Badger is a photographer, architect and photography critic of more than 40 years. His published books include Collecting Photography (2003) and monographs on John Gossage and Stephen Shore, as well as Phaidon’s 55s on Chris Killip (2001) and Eugene Atget (2001). In 2007 he published The Genius of Photography, the book of the BBC television series of the same name, and in 2010 The Pleasures of Good Photographs, an anthology of essays that was awarded the 2011 Infinity Writers’ Award from the International Center of Photography, New York. He also co-authored The Photobook: A History, Vol I, II and III with Martin Parr.