Ken Schles

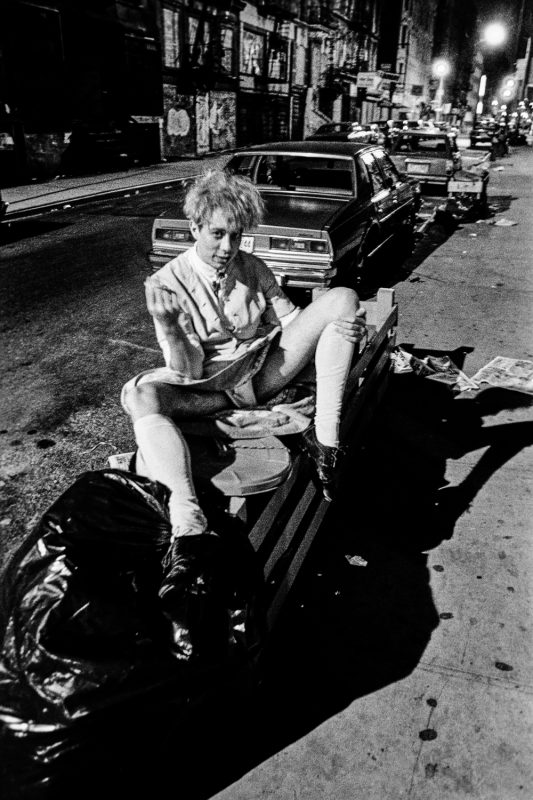

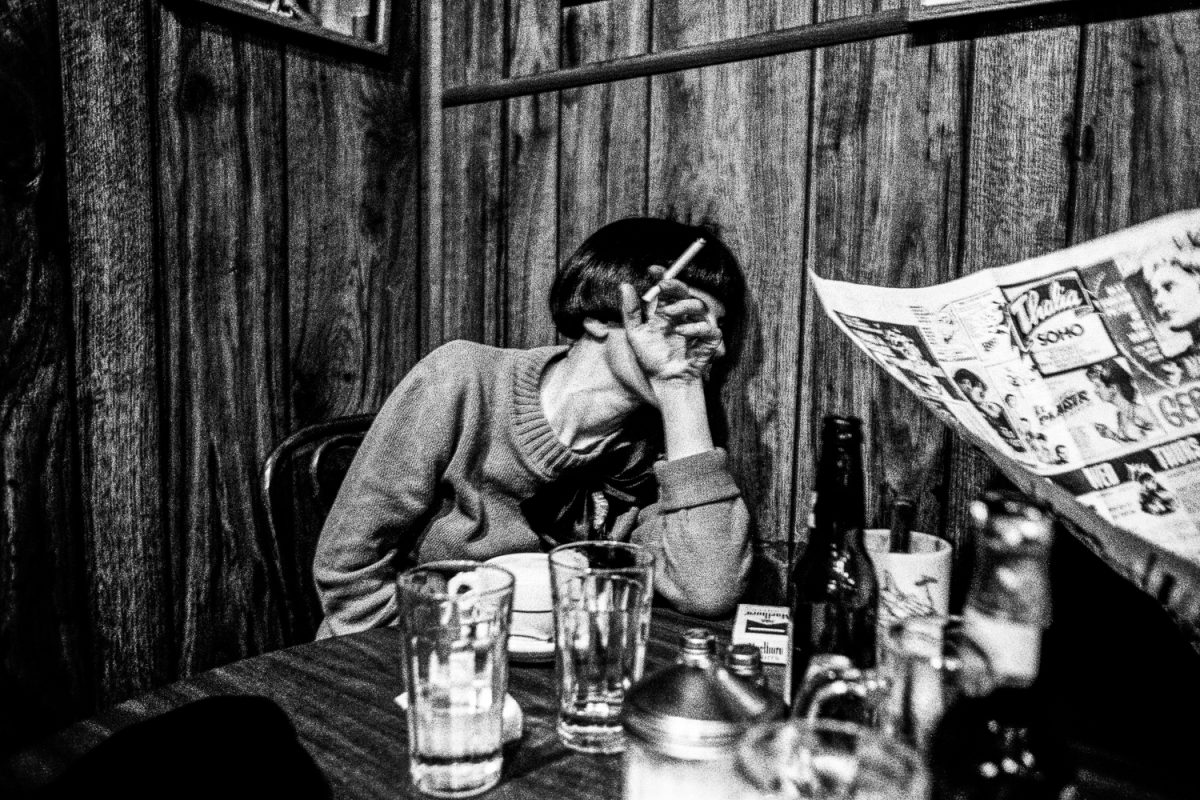

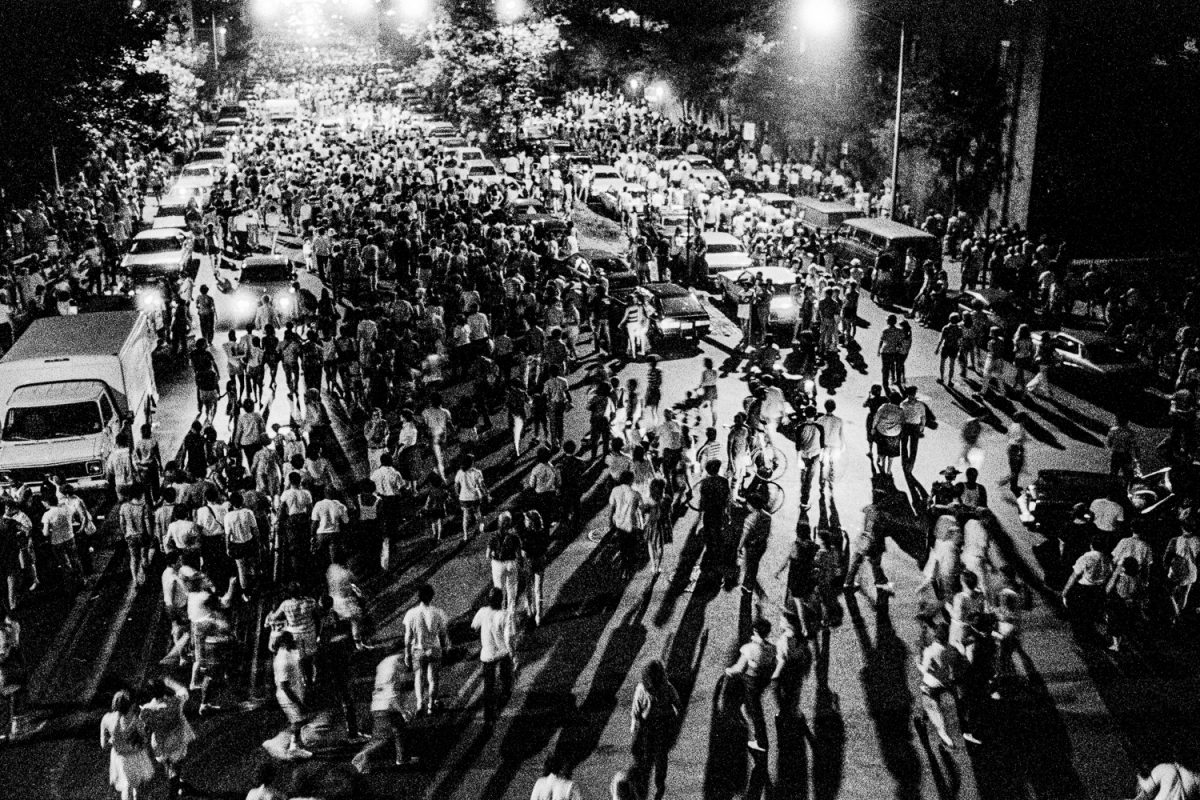

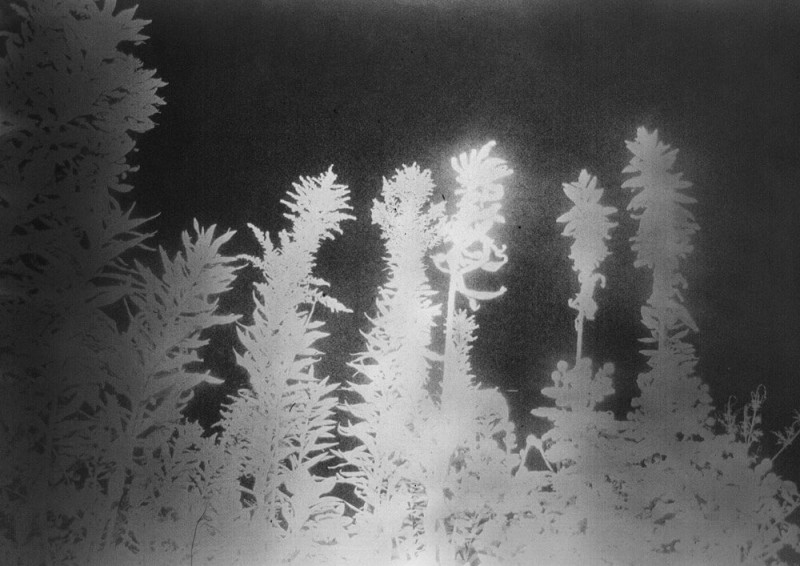

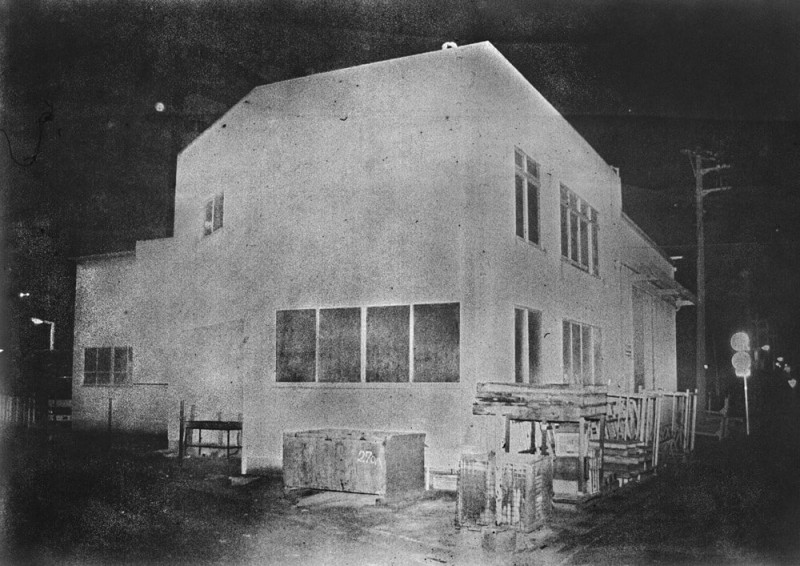

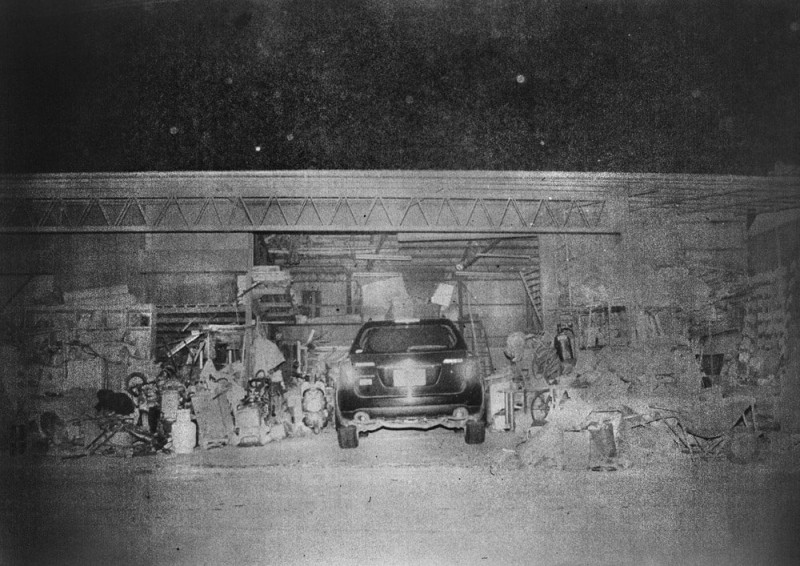

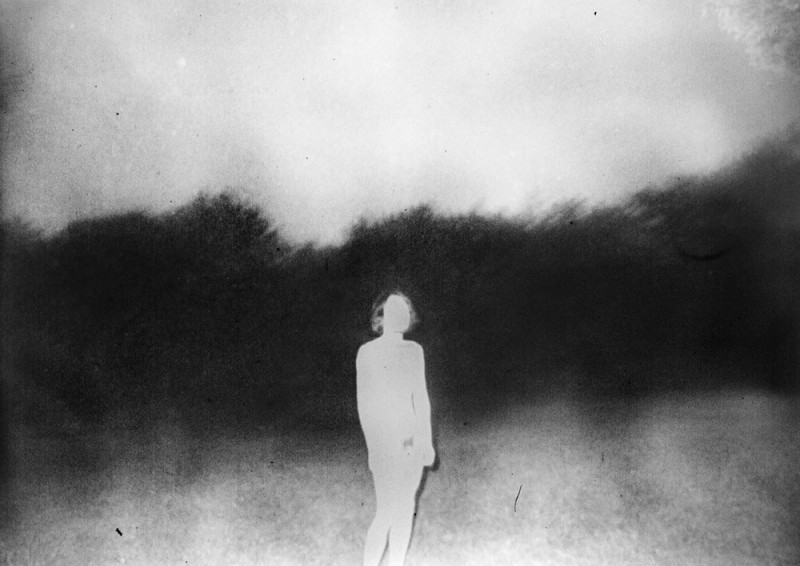

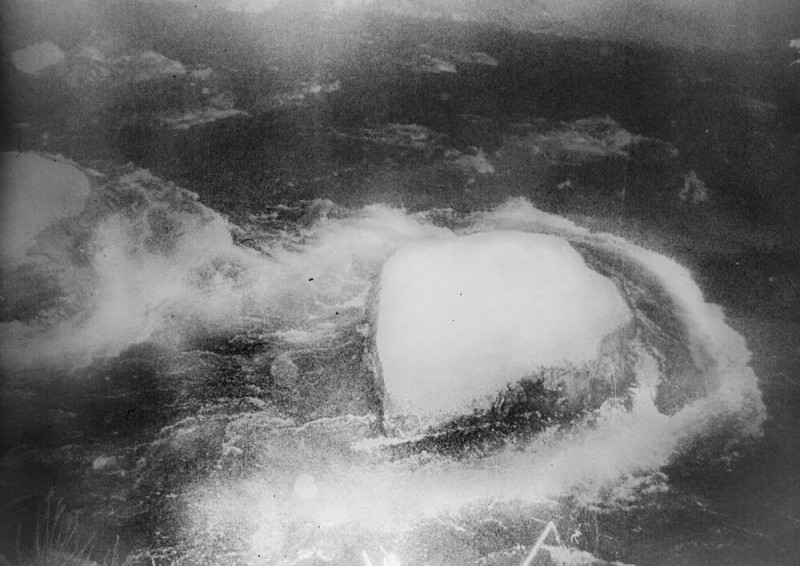

Invisible City/Night Walk

Interview by Peggy Sue Amison

Invisible City was a cult book. After publication in 1988 it very quickly went underground and out of print. The New York Times selected it as a notable book of the year, and after that, it was gone. At the time, some critics rejected the format as too small while traditionalists described my use of bleeds as “anti-photography”. Peter Galassi eventually included Invisible City in an exhibit at the MoMA, but even by then it was already out of print for several years. The book was expensive to own; difficult to find: it was disappearing onto the shelves of collectors.

When the Internet came around Invisible City didn’t have much presence. While known in the photographic community, its unavailability only added to its cult status, something I felt was problematic. It started appearing in volumes on the history of the photobook (or not, which was then hotly debated online). Prices skyrocketed. While valuation for many years hovered around $800 a copy, suddenly it reached $1.2k to $2k a copy. Once I saw Invisible City listed as high as $10,000.

Sitting in his office, Phil Block (one of the founders of ICP and I were talking about how Invisible City, while appreciated by a certain audience, was becoming forgotten to a new generation. I decided it would be nice to make a 25th anniversary reprint, still some five years off. Jack Woody, the original publisher at Twelvetrees Press, wasn’t as keen on a reprint, because the technology for printing in photogravure (the original printing method used) had become obsolete. Much of the beauty and object quality of Invisible City came from this particular process, and this was something neither of us wanted to lose.

Then, in 2011, within a few short months, a multiplicity of events conspired to set the stage for a reprint. These events also compelled me to examine other work from that same period. In the UK, at the University of Coventry, the online group Phonar selected Invisible City as a ‘best’ narrative photobook. Matt Johnston, who helped form the Phonar group, told me he had been developing a personal project through something he called The Photobook Club – an online crowd sourced study of iconic photobooks, in an attempt to bring those projects to a new audience. And – he would enjoy my participation. Independently, Howard Greenberg showed the book to Gerhard Steidl. Howard knew that Steidl had developed a new printing methodology that brought back certain qualities of photogravure and that Gerhard had been interested in reprinting select older titles. He thought Invisible City might be of interest to Gerhard. And Harper Levine, of Harper Books, asked me to make a new piece related to Invisible City for him to display at Paris Photo. Also Jason Eskenazi, approached me to exhibit Invisible City at a photo festival in Bursa, Turkey. Prior to these events I hadn’t considered the work in fifteen years.

There was a shift. A threshold had been crossed. New York City was a radically different place than it had been in my photographs. My work was now connected to a mythologised vision of a pre-gentrified, pre-Internet New York. And photography itself had changed: the way we looked at and shared images had shifted. I think both of these elements conspired to connect the work to another era and sparked new outside interest.

Night Walk grew initially from revisiting some outtakes Invisible City for purposes of discussion. I eventually mined my archives developing these new projects around Invisible City. Gerhard Steidl offered carte blanche for the reprint: I could change the format or add images, as he had done with Kouldelka’s Gypsies or Davidson’s Subway. But I felt strongly that thirty years on I shouldn’t mess with my early editorial decisions for they had become part and parcel of the book’s legacy. I wanted people to see Invisible City in its original form. I played with the Night Walk piece I made for Harper. I continued thinking what might accompany Invisible City’s re-release. Then a galvanising event came with the death of my parents.

My parents died within a day of each other in 2012. In my process of mourning, I thought about the many deaths of people I once knew, especially around the AIDS and drug crises in my early 20s, in the mid-1980s, and the death of my brother around the time Invisible City was published. My parents had been in a long decline for many years, both afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease, which I explored in my book, Oculus. My exploration of the connection between images and memory, in part, was a reaction to their senility. I looked at old contact sheets from my East Village days and remembered all those people who died. I remembered their presence so well. In my mind I could still vividly hear the their voices. And I was struck with the vitality of the people in my images. In a box of Invisible City material, I found a poem by Octavio Paz, called Night Walk. It resonated for me. I became obsessed with making my own ‘night walk.’ What began at first as an exercise now became an obsession: and then a book.

These two books, Invisible City and Night Walk are testaments to both the times they discuss and the times in which they were made. In one sense they are bookends. One made at the time, the other looking back. Invisible City came about when so many cultural phenomena overlapped and existed, for just a brief moment, in one place. I wanted to capture my sense of it before it all went away.

I believe the power of Night Walk comes from me experiencing death and reflecting upon past deaths while looking to these images, these fragments from the past, as totems of death’s opposite. Night Walk is about vitality and ephemerality, things that transcend the book’s focus of time and place. I wrote the following epigraph specifically to address these issues and to focus the reader’s attention on what is to come:

“I lay these fragments before you. What has since been rebuilt now reverts back to its former state of skeletal ruin. The dead reappear, hurry about and whisper their siren songs into your ear. Where once the journey was open-ended and uncertain, it now leads to an inevitable end. The living recognize in the past only what the living choose to remember or refuse to forget. In truth the past never reveals itself so readily or so fully — for even the dead once lived lives of complication and consequence, immeasurably filled with uncertainty and promise.”

For me the significance of the book is not that the book is set in some past, but that it resonates with a presence and vitality that I experience in the present. This is why I ended the book with the quote from T.S. Eliot on the paradox of experience being both absolute yet subjective and why I dedicated the book to the “memory of those who died in the scourge of AIDS and violence that gripped the East Village during the 1980s.”

All images courtesy of the artist. © Ken Schles

—

Ken Schles is an American photographer who has authored five monographs: Invisible City (Twelvetrees Press, 1988; reprint Steidl Verlag, 2014); The Geometry of Innocence (Hatje Cantz, 2001); A New History of Photography: The World Outside and the Pictures In Our Heads (White Press, 2007); Oculus (Noorderlicht, 2011) and Night Walk (Steidl Verlag, 2014). His work is also held in more than 100 museum and library collections throughout the world. Forthcoming exhibitions include Invisible City/Night Walk 1983—1989 at Noorderlicht Gallery from 4 April — 7 June 2015.