Erik Kessels

One Image

Essay by Tim Clark

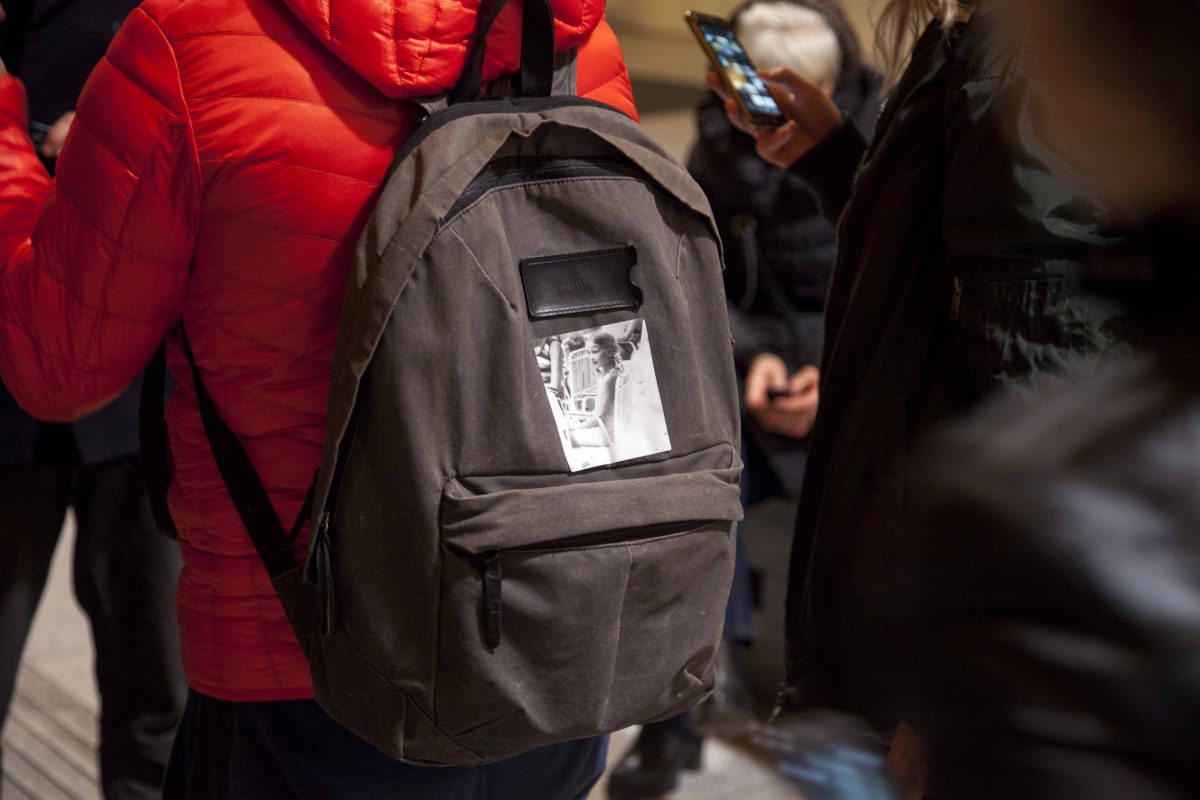

We see you, Susan. We see you adorning the side of a building. We see you on posters and at the bus shelter. We see you fly-posted to the wall. We see you stuck at the lamppost. We see you hanging in the gallery. We even see you in the local newspaper, without warning. We see you here, there and everywhere. Your image hurtles through our consciousness in this exploding and boundless visual world; half-registered but ever present. You are a constellation of small appearances and grand gestures. But it is silence that ultimately binds us, for this is your last photograph.

Aged nine, Erik Kessels’ sister, Susan was killed in a car accident while crossing the street. Following the tragedy, his parents frantically dug around for the most recent photograph of her, finding a typically banal snapshot that inhabited the family album. It was taken by a photographer at a small-town amusement park in The Netherlands, printed there and then and put on the gate for people to buy. They cropped the image in order to isolate Susan as the sole subject, freezing her into a moment of infinitude. This newly-fashioned portrait was then enlarged, printed in black and white and placed in a frame before being hung on the living room wall for posterity. In the process, it assumed an iconic status for these few, select people.

Though generic, the image is now an enigma multiplied, one whose meaning Kessels has rescued from oblivion by placing it in full view to the public across the Polish city of Wroclaw as part of his poetic and deeply-affecting meditation on love, loss and memory. He has done it as a commission for the Photography Never Dies project curated by Krzysztof Candrowicz, enabling this single, brief photograph to undergo a rapid journey from a personal document of grief to public spectacle, conjuring up an absence that perversely translates as momento mori. Because, of course, Kessels has reacted to trauma by behaving like himself – the trailblazing, Dutch artist-curator known for intervening with vernacular imagery and repositioning fragmented lives. In this case, it this life of his sibling, which passes into photography if it passes into anything. Eschewing the protective feelings one normally has towards family photographs, Kessels consequently stirs a curious cocktail of emotions in the viewer; intrigue turns to the guilt that we should not be looking. Even though we witness no drama, we are still gazing at a victim before she became so. She is pictured forever young yet is forever dead – existing outside of time.

As with much vernacular photography (or what John Szarkowski referred to as “oppositional photography”) the image has the appearance of a shabby, discarded picture-postcard that you might find at a flea market – artless, honest and without pretension. Often, disappointingly in visual culture, it is the distressed look that seduces when the old becomes new again. More importantly, beyond the material qualities, is the notion that even the most mundane kinds of imagery surrounding us can have emotional power and depth. The everyday can always become unique – as Kessels notes: “It’s a prescient thought in this digital age when the act of taking a photograph has, for the average person, been transformed from something done to mark an occasion or special moment to an almost daily habit. All of us walk around with thousands of images of our everyday lives locked away in our phones, collections of pixels that we seldom glance at, and on the whole they mean absolutely nothing to us. That is, until they do.”

The vernacular genre of photography is vital to our imagination not least because snapshot photographs can be and repurposed and interpreted variously; they can be recycled, clipped, cut, remixed and uploaded. Yet for transformation to occur they somehow always have to be demystified in order to remystify. That way images can be made to do anything, made into endlessly different narratives since they are ultimately ambiguous. They all have the potential for meaning in the hands of those with cultural or creative intelligence, and our relationship to them can change dramatically over time.

Kessels echoes this sense of a shifting relationship in his inaugural book from the legendary series, In Almost Every Picture: “And now we see the pictures in a way that was never intended. We have the chance to look inside a private collection of private memories. And, in so doing, our memories, or ideas for their memories, overlap, overwhelm and extend the existing memories in these images, these moments recorded on film …

What we photograph today can have continued meaning in a time and place somewhere else, to someone else. What we then find is that we are all involved in every moment. We are all somehow included in what happens to all of us. We are collectively having lives, memories and futures.”

Therein lies the feeling that we can enter the image, which is essential to the democratic virtues of vernacular or amateur photography. As it flies in the face of ideas of privacy and ownership, we suddenly find ourselves responsible for the passage of such images through culture and history, often undermining the concept of authorship as well as resisting the dominance of the market or reputation of the photographer as a result. Such practitioners, whose career is largely underwritten by print sales, are more or less part of a rigid commercial system that operates on the basis of name photographers, limited edition works, the importance of provenance and the vagaries of the gallery world. Politely existing outside of this elitist sphere is the empirical mass of photography, continually evolving as a dynamic and viable area of study, appreciation and even collecting, thus representing a significant challenge to the predominant history of photography. Here, in Kessels’ image, is an indication of the medium renormalised within the everyday aesthetic of culture, since everything and everybody is touched by photography.

The assertion that photography has become utterly central to how we represent, construct meaning and communicate in the world around us presses harder when we consider the upshot of Kessels’ decision to site the image of Susan publicly. In this realm, the unselfconscious display of an intensely personal snapshot throughout the city relies upon an ethical contract between him and society. Such an intervention not only certifies the existence of an otherwise invisible stranger but one whose likeness is now shared by choice and in turn overshared as a consequence. The past maybe gone but we cannot never escape the presence of the dead completely since photography never dies. And at this meeting point between past, present and future, we see you, Susan. We see you. Living among us, you are after all what makes us human. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist © Erik Kessels

This article was originally published in Photography Never Dies and has been reproduced with kind permission.

—

1000 Words Julia Margaret Cameron: Influence and IntimacyGathered Leaves: Photographs by Alec SothPeter Watkins: The UnforgettingRebecoming: The Other European TravellersFOAMTIME LightboxThe TelegraphThe Sunday TimesPhotoworksThe British Journal of Photography