Regine Petersen

Stars Fell on Alabama

Essay by Lucy Davies

Stars Fell on Alabama is the first chapter in Regine Petersen’s series on meteorites, titled Find a Falling Star. It is a configuration of archive press cuttings, eye witness reports, interview transcripts, genealogy and found images, fleshed out with quiet, contemplative photographs taken in the field.

She began the project in 2009, having chanced on the story of the Hodges meteorite. What began as an investigation into a single stone, though, has branched into a lightning rod touching memory, history, magic and mortality; human relationships and religion; race, slavery and colonialism. It also considers the practice of storytelling itself – whether an author/photographer can tell a story without casting their own shadow over its content.

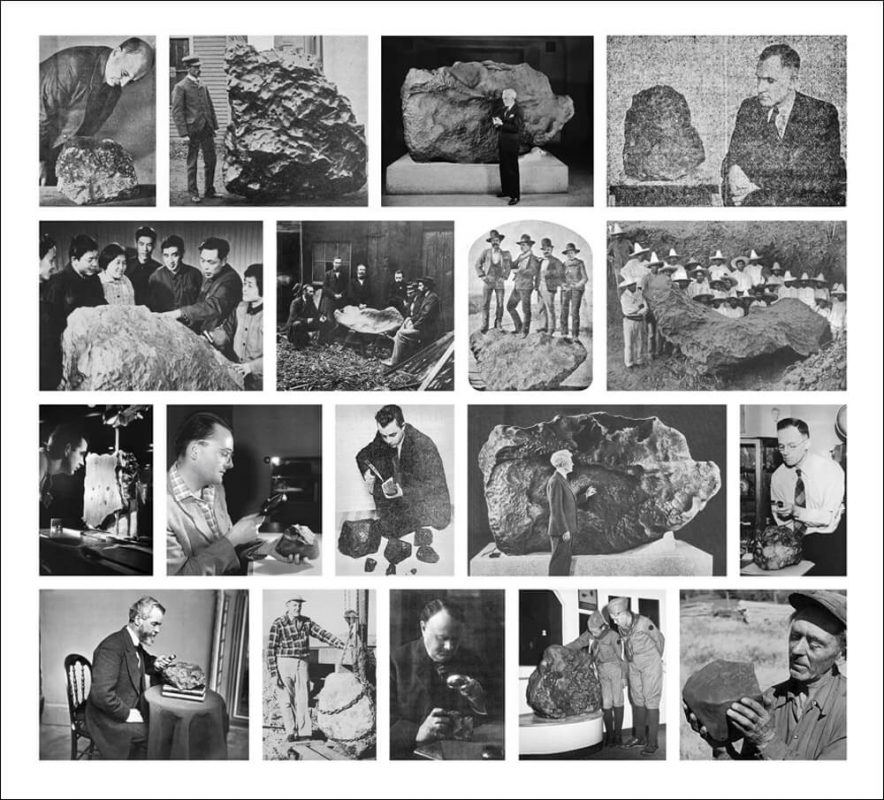

Meteorites are pieces of asteroid, leftovers from the formation of the solar system 4.5 billion years ago. They are highly prized by scientists, who find in their solid, iron and stone mass clues to the infant universe. Of the several thousand that make the fiery plunge to earth each year, most are lost in the sea. Others become cosmic dust and disperse, but each year a great number make contact with the ground. Most fall without consequence. Most that is, not all.

On 30 September 1954, an eight pound meteorite fell on a house in Sylacauga, Alabama. It crashed through the roof, bounced off a console radio and hit 31 year old Ann Elizabeth Hodges on the hip while she was napping on her sofa. A photograph from the time included in Petersen’s anthology shows the woman with two policemen. Her brow is furrowed, her hands nervous, and no wonder. As well as extensive bruising, the incident brought a Special Forces investigation to her door, a flurry of media attention, a bidding war, a lawsuit, divorce, betrayal and a breakdown. This is the event on which Petersen’s project pivots, although as we shall see, its remit is much wider.

The rock, still boasting the tar it picked up en route through the roof, now resides in the Alabama Museum of Natural History, where Petersen travelled as part of her research. The curator removed it from the glass case. “He said ‘you can touch it, you can take it in your hands’ and I knew he was looking at me and I thought, I have to feel something now, I have to connect to the history of things, and it was just impossible. Later though, when I photographed it, it was quite different,” Petersen explains.

Petersen has compiled eyewitness accounts from the time, detailing bright flashes and fireballs smoke, television interference and bicycle accidents. In Phoenix City a woman thought it was a flying saucer: she “saw a man get out of it.” The disparity that exists between these reports is something that came to fascinate her. “People misremember. It all starts with an idealised story that sounds a little bit like a fairy-tale and then you go below the surface and it gets more and more complicated.”

She also includes the transcript of an interview with Ann Elizabeth’s husband, conducted in 2005. Eugene Hulitt Hodges was out when the rock hit his white-frame house, and returned to find some 200 reporters on the scene. He spent months fighting his landlady in court after she sued for possession. Collectors lost interest, so he used it as a doorstop for a while, then Ann Elizabeth donated it to the museum, against his wishes. They divorced a few years later, both citing the meteorite as primary cause.

In the transcript, Eugene is questioned about the events. The interlocutor, ‘Bill’, is visibly massaging his subject’s answers, disagreeing with him: “The way I remember you telling me is…Here’s what I remember…Here’s what I know and you tell me…”

‘Bill’, though, had a motive. He wanted to make a film, but the catchy plot he wanted wasn’t what Eugene remembered. “I had the feeling he wanted to direct the events,” says Petersen. “But I’m not critical. I’m in the same position: I want to make a story, to find out what happened, but I learned it’s absolutely impossible. People forget a lot and they idealise a lot.”

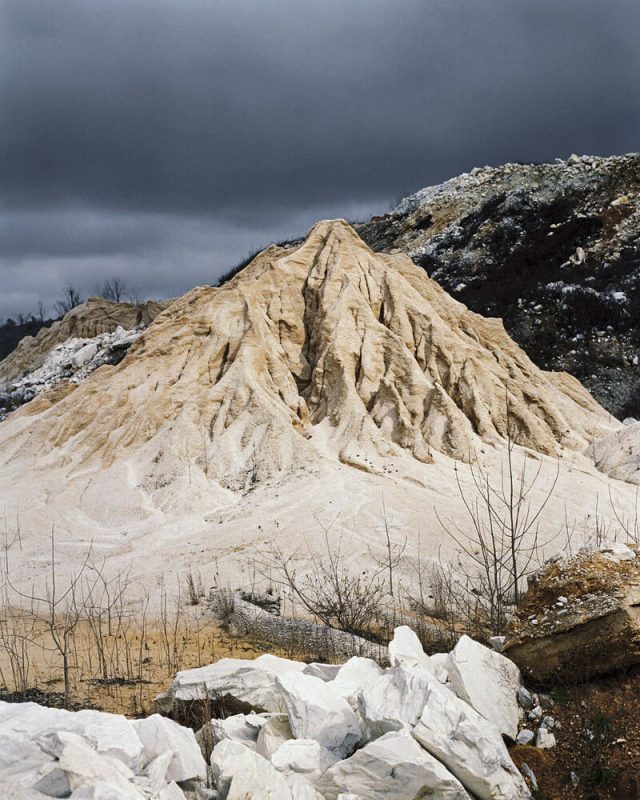

To compensate, Petersen decided she needed to find truths of her own first hand, with her camera. She photographed the muddy earth of the impact site. She rented a car and drove to Talladega forest, the local junkyard, defunct marble quarries. Sylacauga is known as ‘Marble City’ and huge chunks lie everywhere in the dust. “I liked the idea of the two coming together; the thing from space and the marble from the earth,” she says.

Strange things began to happen. On the day she visited the cemetery to find Eugene’s grave (he had died two weeks before she came to Alabama) men were assembling his gravestone. Ghostly patterns appeared in the depths of the forest. When she visited an old slave plantation a dog with one blue eye and one brown came out of nowhere and sat in front of her. “The photographs I took are like apparitions. It felt like everything just came towards me of its own accord.”

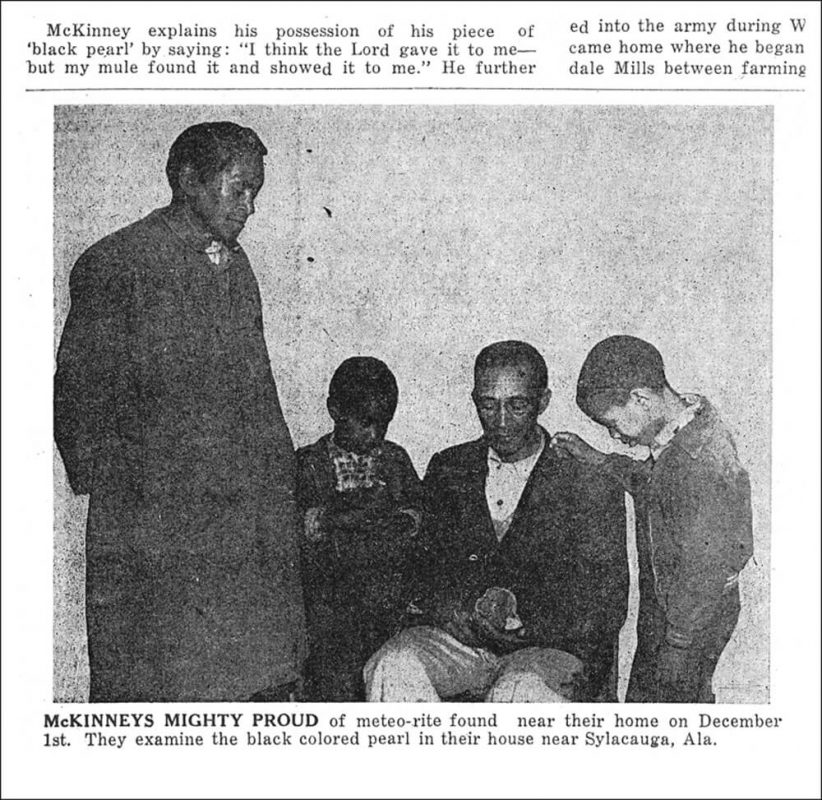

The day following the Hodges incident, a 60 year old farm hand named Julius McKinney discovered a second fragment of the meteorite in the middle of a dirt road. His mule shied away from it, and in the dark he thought it was a snake and left it alone. It wasn’t until he heard about Ann Elizabeth Hodges that he retrieved it, but because he was black, and this was Alabama, and the Civil Rights Act was still a decade away, he hid the rock under his bed, frightened he wouldn’t be allowed to keep it.

Several months later he told his postman, the only ‘official’ person he knew. He arranged for McKinney to meet a geologist, who in turn helped arrange a sale to the Smithsonian. The money furnished McKinney with enough to buy a farm and a car outright.

Petersen includes cuttings from the Ironwood Daily Globe, and Avondale Sun, the last including a photograph of the McKinney family, with the “black-colored pearl”. She also includes a photograph of the original negative, retouched crudely by the newspaper with white paint to cover the extreme poverty the McKinney’s lived in. In 1954 Alabama, people liked their reality watered down.

Also included are accounts from an 1833 fall large enough to be visible all over America, including Alabama. “I like these layers of history,” says Petersen. Prophet Joseph Smith recalls “the long trains of light… like serpents writhing…it seemed as if the artillery and fireworks of eternity were set in motion to enchant and entertain the Saints, and terrify and awe the sinners of the earth.” A slave recalls her “tellin’ some of the slaves who their mothers and fathers was, and who they’d been sold to and where…they thought it was Judgement Day.”

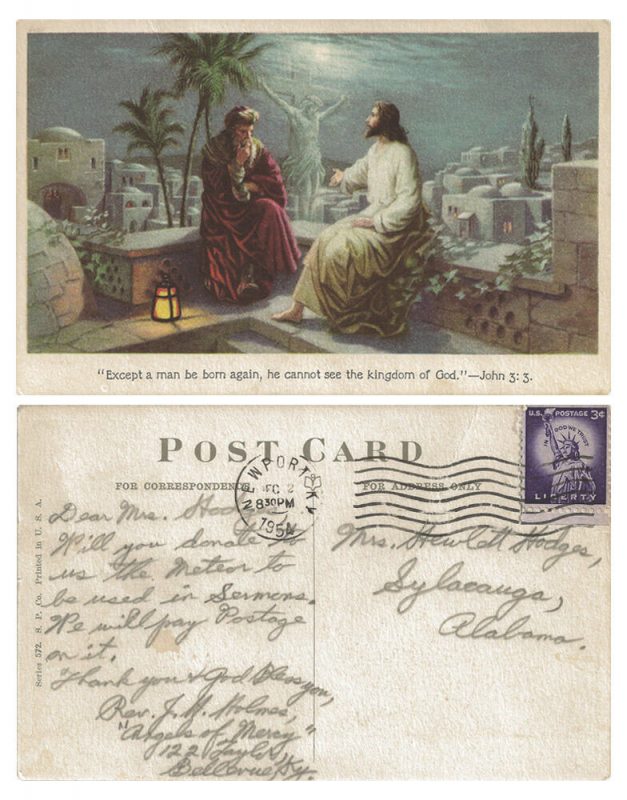

It is the way in which Petersen’s work swings gently between religion, science and superstition that provides the golden thread binding it together. Her own magical thinking for example, or Julius McKinney believing “the Lord gave [the meteorite] to me” and a postcard sent to Ann Elizabeth Hodges from a church in Bellevue, Kentucky pleading for the rock. Inserted between Petersen’s photographs of anthills and cotton plants and discarded snapshots in the dirt are scientific images of planetary bodies far away in the night sky, as she switches ably back and forth between microcosm and macrocosm. The fragility of human life in the face of the cosmos lurches into view.

Next, Petersen will travel to Calcutta, where a collection of meteorites has been kept hidden for years after locals tired of seeing their space loot packed off to the Natural History Museum during the years of the Raj. She has already been to a town in Westphalia, Germany where three children witnessed a fall in the 1950s.

Petersen has no idea how far the project will take her. One thing is certain, she has rich pickings ahead. It’s impossible not to be fascinated by these stories, which contain as much rich detail about human fallibility as the rocks contain about the beginning of the universe. “I don’t think my friends feel the same,” says Petersen. After all these years, they say ‘Ah, the meteorites again.’”♦

Born in 1976, Hamburg, Regine Petersen received a Diploma in Communication Design & Photography at the University of Applied Sciences Hamburg in 2006, and went on to graduate from the MA Photography course at the Royal College of Art in 2009. Petersen has had her work exhibited internationally including at the House of Photography, Hamburg; Museum Folkwang, Essen; James Hyman Gallery, London; and Aperture Gallery, New York.

Her most recent and ongoing project Find a Falling Star, has been nominated for the National Media Museum First Book Award this year. It was exhibited in 2011 at the Lunar Planetary Lab in Arizona, complimenting the Southwest Meteorite Collection; at Galerie Jo van de Loo, Munich; and most recently at the B2 Institute, Oracle, USA with Geoff Notkin.

Petersen’s work has been featured in publications such as Photographies, Material and Camera Austria, and she one the National Media Museum Bursary. She was a finalist of the Saatchi New Sensations Prize 2009, and has most recently received funding from the Arts Council Hamburg, as well as been shortlisted for The Discovery Award as part as Les Rencontres d’Arles 2012.

All images courtesy of the artist. © Regine Petersen