Nadège Mazars

Mama Coca

Essay by Sergio Valenzuela-Escobedo

In the context of a trio of research-based photographic exhibitions built around the idea of self-governance for Fotofestiwal 2023 in Łódź, Poland, curator Sergio Valenzuela-Escobedo focuses on Mama Coca by Nadège Mazars, a documentary project which tells the story of the Nasa people of Cauca, southwestern Colombia, indigenous tribes who came into conflict with the Coca-Cola corporation – a canny reminder that rejecting the consumerist spiral and questioning the dogma of growth is one way we can rediscover our connection with the earth.

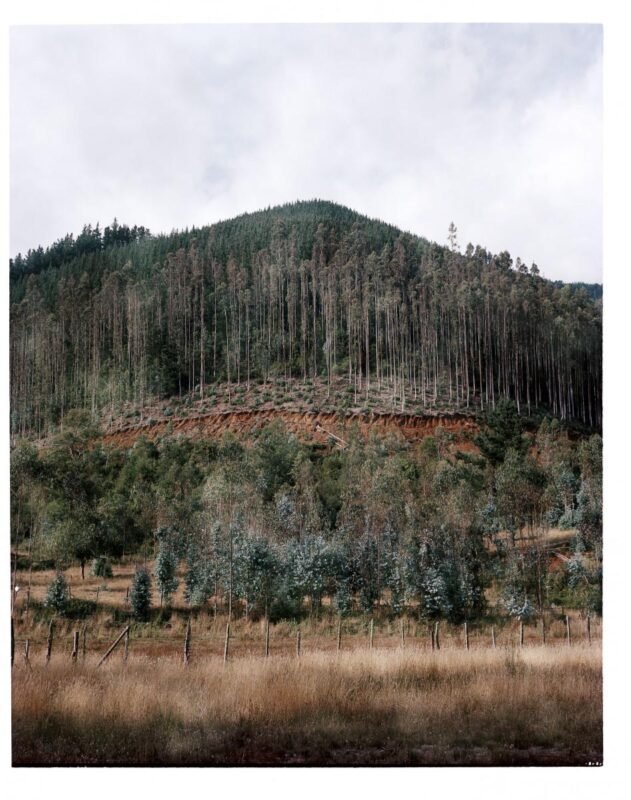

The Nasa people of Cauca, southwestern Colombia have a long-standing tradition of indigenous activism. To support their territorial and political autonomy, they established the Indigenous Guard (Kiwe Thegnas or Kiwe Puya’ksa) more than two decades ago as an organisation dedicated to preserving and passing down indigenous culture, including the traditional use of coca leaf, to younger generations. The indigenous guards carry symbolic batons that represent their responsibility to the community, as opposed to being used as weapons. Comprised of women, men and people of all ages, including children, the indigenous guard courageously confronts the violence and actions of armed actors involved in the expansion of illicit crops, such as cocaine. They risk their lives to protect their territory from the disharmony caused by these crops, which disrupt socio-economic relations and contaminate water sources with harmful substances. Cue Nadège Mazars, whose powerful documentary project, Mama Coca, explores the diverse methods employed by the indigenous guard to educate their community about their political and spiritual responsibilities with the view to fostering respect for their traditions among Colombians and Americans alike.

Coca leaf products have deep cultural and medicinal significance in Andean communities. Whilst coca is the source of cocaine, it is also believed to possess healing properties and amongst the Nasa people in the Colombian Andes, chewing coca leaves is a vital part of their rituals, symbolising harmony and reverence for the land. The use of coca leaves has a long history, made evident in pre-colonial stone statues and the spiritual practices of Nasa healers. In the Amazon, coca leaf flour aids in meditation and wisdom-seeking. Socially, the “mambear”, chewing coca is practiced in communal spaces, fostering collective knowledge. In the Inca Empire, coca was sacred and restricted to the elite, used for anesthesia in surgical procedures. As recent studies have shown, coca plantations date back more than 8000 years. Balls of coca leaves were even found in the mouths of pre-Columbian mummies.

Today, coca is of course primarily associated with the production of cocaine, leading to its prohibition along with the drug itself. The stigmatisation of coca traces back to the arrival of the Spanish in the Abya Yala continent, where it was demonised and banned due to its perceived association with the devil and regarded as a hindrance to Catholic conversion. However, there was a contradictory approach to coca during colonisation, as it was also promoted by colonial elites to enhance the productivity of indigenous workers in harsh mining conditions. This history of moral stigmatisation during colonisation has had a detrimental impact on the culture and social cohesion of indigenous communities and, consequently, the contemporary valorisation of coca as a sacred plant with significant cultural importance plays a crucial role in the indigenous struggles in the Americas. It speaks to ideas of autonomy, ancestral territories, distinct culture and spirituality for indigenous peoples, reaffirming their identity and resisting the destructive effects of colonisation.

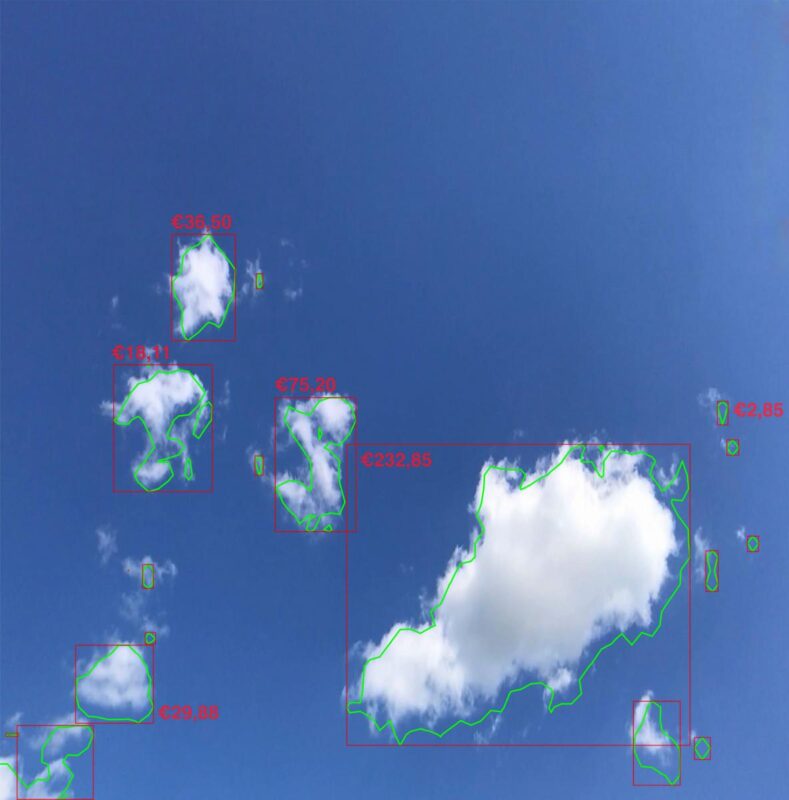

The conflict between multinational company Coca-Cola and indigenous Colombian company Coca Nasa revolves around the use of the four letters that represent the plant’s name. The Nasa people have been cultivating coca leaf for centuries in the Colombian mountains, making various products derived from legal processing, including food, beverages, herbs and natural medicines. In late November 2021, Coca-Cola demanded that Coca Nasa remove a beer named Coca Pola from the market, claiming it to be a case of plagiarism. In February 2022, representatives of the Nasa and Embera Chami peoples sent a letter to Coca-Cola expressing their concerns. They argued that the use of “coca” without consulting indigenous peoples is an abusive practice, violating national, Andean and international human rights norms. The letter demanded explanations and threatened to ban the sale of Coca-Cola products in indigenous territories. Since then, Coca-Cola has remained silent, potentially due to the fear of being implicated in the appropriation of traditional indigenous knowledge and facing a scandal. The legal battle remains unresolved.

Throughout its history, the original recipe for Coca-Cola is said to be one of the most closely guarded secrets in the world. However, in 1988, one of the company’s leaders acknowledged the presence of coca in the beverage. In an advertisement from the Scientific American magazine dated 7 July 1906, a photograph of two natives of the Andes region appeared alongside the caption: ‘These people endure their hardships more easily by chewing Coca leaves daily.’ It is believed that, for many years, Coca-Cola imported coca leaves, which were likely decocainised before use. The company seemingly obtained a special permission that allowed them to legally bypass international anti-drug laws, which restricted the sacred Inca plant within the borders of its native countries. This created an international monopoly on the use of the coca plant, whilst small indigenous companies like Coca Nasa face strict prohibitions on exporting their coca-based products.

However, within the concept of self-governance, a refuge of hope becomes apparent. Three separate, but linked, exhibition presentations at the recent Fotofestiwal 2023 in Łódź, Poland this summer bear witness to this model and are all driven by the following question: how are new forms of self-organisation practically structured in conjunction with political and legal autonomy in tandem with traditional and natural authorities to control the implementation of developmental projects?

The model of self-governance continues to be the subject of numerous theoretical debates but here the intention was to examine just three isolated cases within a broader range of issues present on the continent: the complex process of building a collective that has evolved over 40 years following the failure of Werner Herzog’s filming of Fitzcarraldo (1982) in the Peruvian region of Alto Marañón, as investigated in Ipáamamu – Stories of Wawaim by Eléonore Lubna and Louis Matton; a rebellion initiated by a group of Purepecha women to protect the Uauapu ritual, resulting in the expulsion of one of the most dangerous drug cartels from the city of Cherán which forms the basis Oro Verde by Ritual Inhabitual, and of course Nadège Mazars’ Mama Coca.

To comprehend this model, it is necessary to understand the key factors that have ancestrally contributed to preserving the activities of each community, identifying their customs, problems, adaptations and current situation. In these countries, the communities are surviving despite the lack of recognition and interest from different companies and state entities, despite national and international legislation protecting their rights and heritage. Therefore, the purpose of these exhibitions is not to shed light on the current context of the respective communities’ everyday activities and lives, but to demonstrate how they have survived and what methods of defense they have employed against various threats, such as the arrival of foreign film productions, the advent of the avocado industry, or the threat of a lawsuit from a US multinational corporation. Each exhibition offers a critical perspective on the concept of self-governance whilst underpinning an attempt to present the holistic nature of the research that allowed the photographers to comprehensively unveil the historical and ideological realities.

Ultimately, these events are part of a war against nature. Their magnitude and violence should not be underestimated. In this context, how can we restore peace, democracy and hope? The options are numerous: rejecting the consumerist spiral, questioning the dogma of growth and rediscovering our connection with the earth. All these commitments share a common ground: they are a response to a system doomed to failure. Each of these acts of resistance points us to the necessary paradigm shift in order to continue building a peaceful and resource-rich planet. However, beyond individual actions, how can we bring about a collective societal shift towards more sustainable lifestyles?

The hope is that we can emerge from this with our heads slightly bowed, our anthropocentric pride humbled, with greater respect for the fact that other cultures have been able to establish a wiser relationship with their surroundings. But for that, we must be willing to sacrifice something. What are you willing to lose? What is your hope? ♦

Fotofestiwal 2023 ran from 15 – 25 June 2023.

—

Sergio Valenzuela-Escobedo is an artist, researcher, curator and author working both in Chile and abroad. Since 2016, he has curated exhibitions including Mapuche (Musée de l’Homme, Paris, 2017), Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation which has been on tour under his supervision and Geometric Forests (Les Rencontres d’Arles, 2022). He holds a PhD in Photography from the École Nationale Supérieure de la Photographie (ENSP), Arles. Valenzuela-Escobedo is also an artistic director and co-founder of doubledummy studio, a platform that creates a space for producing and showcasing critical reflections on documentary photography. He is a member of the jury for the Arles Book Award and a member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). His writing has appeared in Inframince, 1000 Words and Mirà.

Images:

1>6-From Mama Coca © Nadège Mazars.

7>9-Installation views of Nadège Mazars: Mama Coca at Fotofestiwal 2023, Łódź, Poland, 5 – 25 June 2023.