John Myers

The Guide

Book review by David Moore

David Moore discusses John Myers’ documents of domesticity and de-industrialisation in the Midlands region of England whilst considering the value in revisiting an already-familiar view.

In his essay “The Artist as Anthropologist” (1975), Joseph Kosuth asked: ‘why not have the anthropologist […] anthropologize his own society?’ He concluded, some paragraphs later, that the ‘artist – anthropologist’ would make a better job of it, addressing territory familiar to themselves, mapping an ‘internalizing cultural activity in his own society and within his own social matrix’.

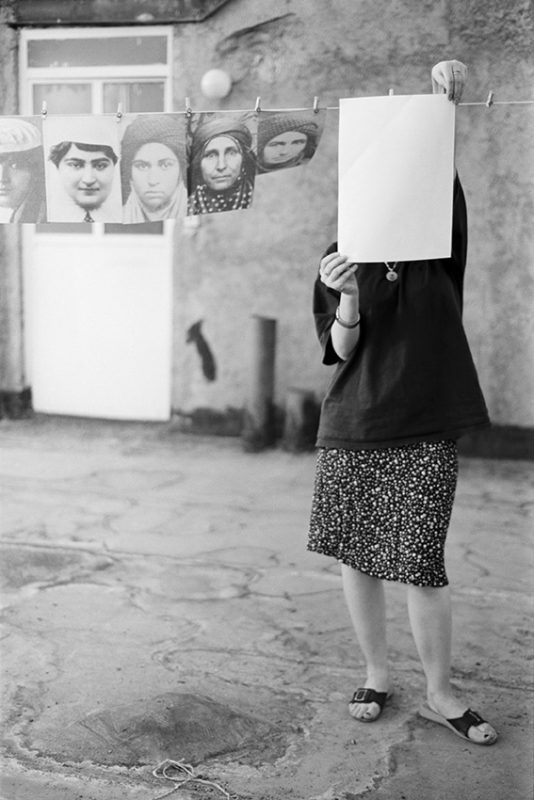

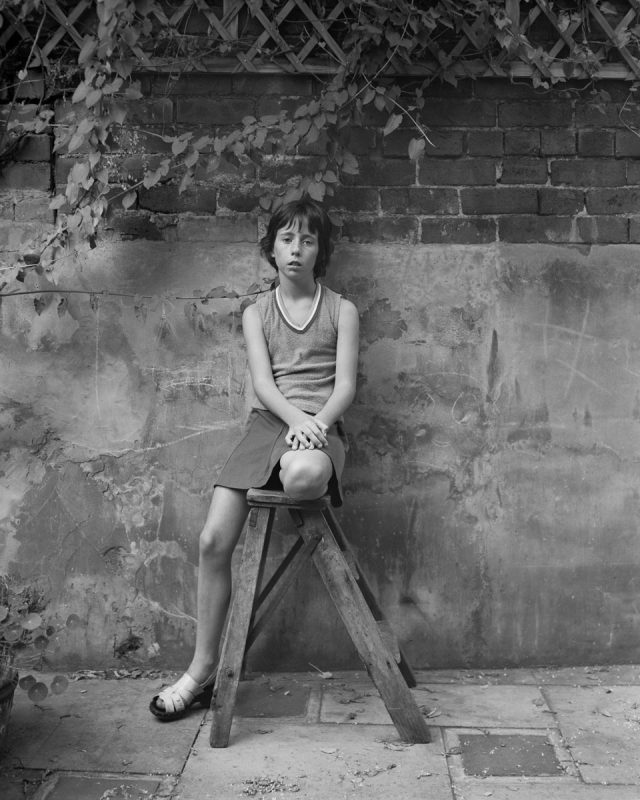

John Myers’ The Guide arrived, an overview of differing collections of black-and-white photographs from the period 1972–88, published by RRB Photobooks. I am familiar with the territory represented; not only as a photographer but also as a fellow Midlander. Growing up there in the ’70s, I was a contemporary of some of the younger children portrayed. I recognise the patios, the Little Red Riding Hood coats (my sister had one), pet rabbits on suburban lawns and the general décor of the wider environment. Myers lived within this cultural matrix before photography had ever entered his life and because of this, as viewers, we find ourselves already beyond a particular veneer, already within the interior.

Yet, such proximity has to be negotiated. The work’s raison-de-etre is the everyday, and photography’s limitations are such that when we look at what is close to us, we might need reminding of its value. Myers opens up the process through a valuable first-person commentary that echoes the visual work in its deadpan style that helps avoid a simplistic reading of the series as any average survey of English suburbia, contextualising his methods and preventing some photographs from being overlooked, not because the images are badly made or too easily described, but because of their much-discussed banality.

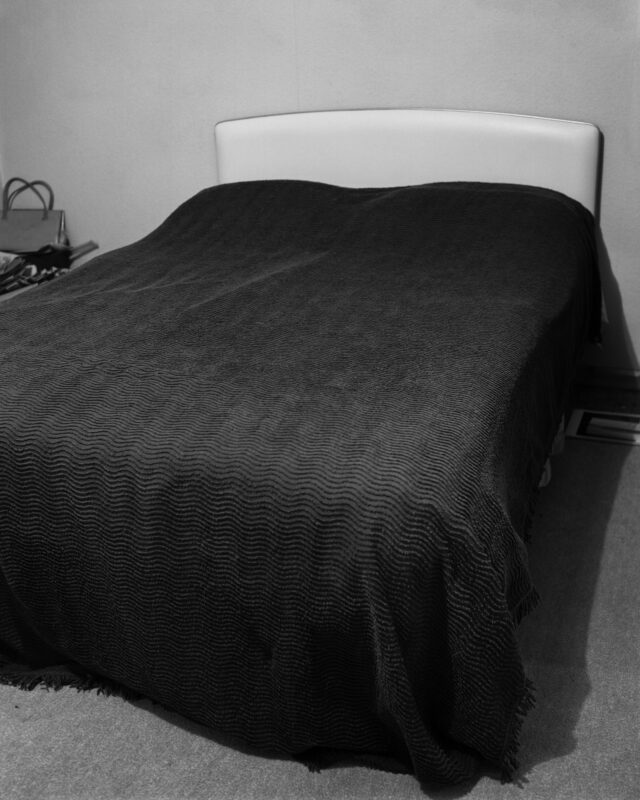

That the pictures are ‘boring’ is continually emphasised, yet one viewer’s ordinary is another’s spectacle. To photograph something is to monumentalise it, allowing the uncanny to emerge. Of Myers’ work in this collection, this is most true of ‘The Bed’ (1976), where the cavernous tones of such a benign object propose latent fearsomeness within the candlewick bedspread that almost fills the frame. I’m reminded here of the surreal experimentation of Bill Brandt’s domestic interiors, but here, there is no such trickery with perspectives, just a fairly straightforward view.

The ‘Furniture Store’ (1974) photographs too are astounding in their revelations. A small series of photographs showing simulacra of family living rooms in shop windows; artlessly arranged and underlit, perform as an abeyance to a petit-bourgeois compliance and “Home in time for tea at 6” that sets the tone for much of Myers’ consumerist backdrop.

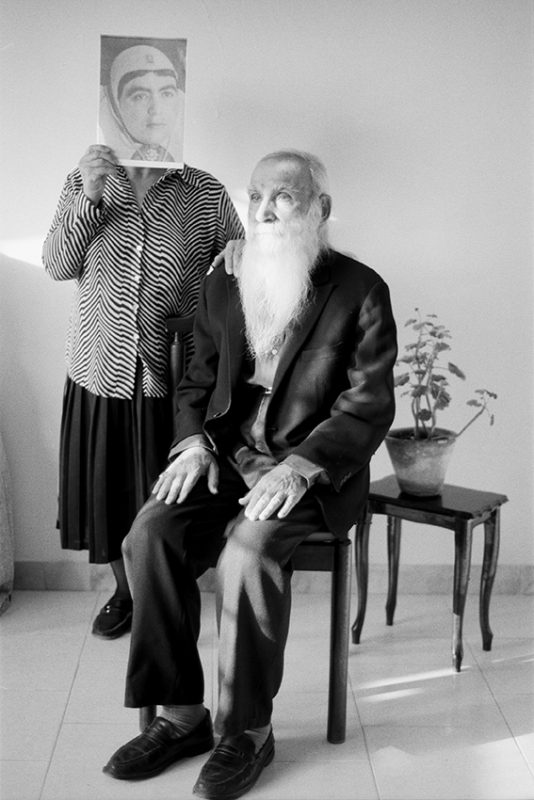

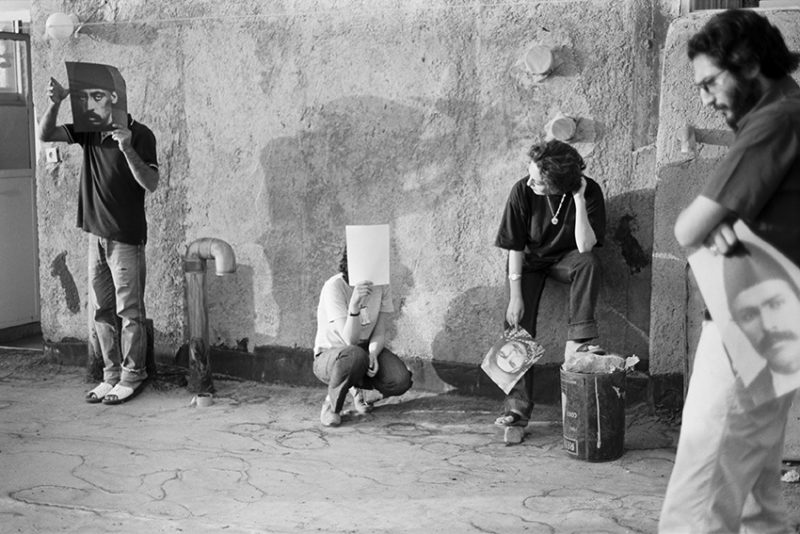

These, and the majority of the portraits from The Guide, are complex and understated photographs. Myers makes the point that, throughout the making of these works, whilst influenced by various histories of photography (and presumably a history of art), he was never funded and never intended for the pictures to form ‘a project’. He ‘just took them’, no exhibition in mind, no wanting to please anyone but himself and his sitters, no business plan. His own description of his practice gives the impression that photography is a thing that happened to him, and that the pictures were just there. This is also evidenced in an apparent non-interventionist method of working, as Myers tells us of a subject adjusting his sitting position. “Don’t move”, thought Myers, as though an entire contract would collapse if he actually directed a pose for the camera; all had to occur around him to be valid.

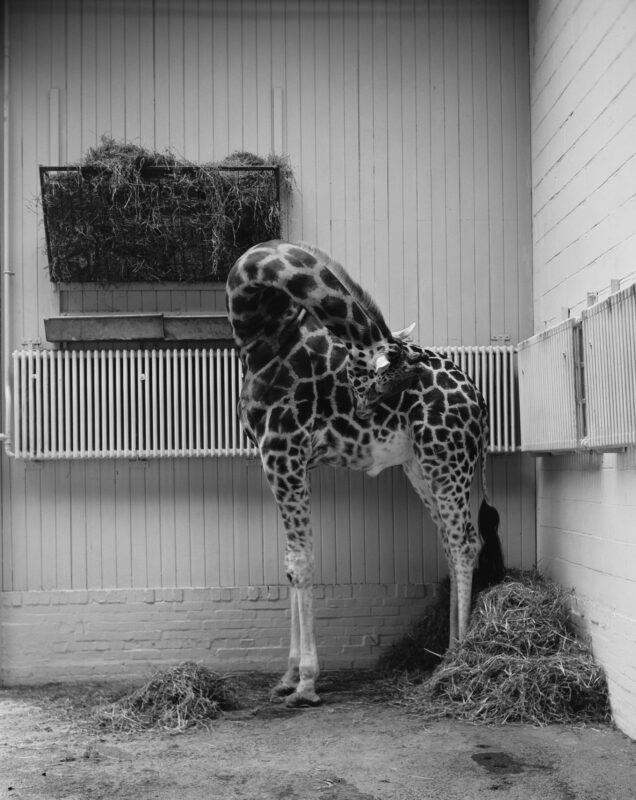

Myers’ photographs resound most impactfully when closer to home and working within familiar territory, and ‘The End of Industry’ (1981–88) series, that sees the book out, feels out of place in this collection, addressing a quite distant socio-political discourse, away from the suburbs. He writes, quite honestly, that he ‘ran out of steam’ and, in contrast to the aforementioned, non-interventionist position, was, at one point, out ‘looking’ for photographs. These images employ similar visual grammar to many of the ‘domestic’ images within The Guide and again are opened up by Myers’ commentary. The photographs of ‘The Female Brickworker’ (1983) particularly articulate this, locating the subject of the picture within an industrial context that, quite feasibly, might exclude her from the relatively affluent environs of Myers’ usual territory. In spite of the eloquent visual record of de-industrialisation during this period of history, one might consider that, within this publication, the idea of ‘old industry’ was a diversion; one with which Myers may not have needed to walk the extra mile, but sit it out at home, to see what happened.

Such inclusions raise questions of the book’s purpose beyond the commodification of a familiar view, particularly where the works have been previously published and are obvious best-sellers. Besides the fast-moving desires of collectors to acquire such objects, this may be understood in a variety of ways. But given the premium prices for his other publications, I was left thinking that this collection’s primary role is in making some of Myers’ work affordable to a larger audience.

As Myers acknowledges his influences, we find familiarity within the photographic precedent, and, as an admirable gesture of transparency by the artist, the roll-call of photographers is welcome. His straightforward list of snappers orientates the viewer towards Myer’s own photographs in a highly specific manner that opens up endless imagining.

As we regard Myers’ photographs in the 21st century, we can understand documentary photography as a particular artifice within the visual overload of the contemporary. The historical period represented here was, in reality, a flammable construct of new social realities in colour, offering entirely different interpretations of social history. Yet, Myers’ was a response that was satisfyingly redolent of the time; a confident interpretation of the histories within his own back yard and a reliable anthropology of the near.♦

All images courtesy the artist and RRB Photobooks © John Myers

—

David Moore is a photographic artist and the Principal Lecturer for Documentary Photography and Photojournalism at The University of Westminster, London.