Sondra Meszaros

Redrawing Power and Pleasure

Essay by Sara Knelman

Sondra Meszaros, who lives in Calgary, Alberta, was in New York in the midst of a residency program at the International Studio & Curatorial Program in 2018, when her studio was flooded by a Spring storm. Her work and all the archival material she’d brought with her was decimated. Ever resilient and resourceful, Meszaros set out to track down new sources of inspiration, and to begin again.

Recently, Meszaros had been amassing an archive of photographic imagery of the female body, as a way of thinking through the aesthetics and power dynamics of sexuality, ideas that are also central to her teaching practice at the Alberta College of Art and Design. Her parameters are loose: the images she is drawn to are often from books and magazines made in the first half of the twentieth century, but their makers and contexts, their moods and styles are not uniform. Indeed, she confesses she is intrigued by images that initially confuse her, a response she hopes her work can start to unravel. Her hunger for new imagery is seemingly insatiable, and her constant searching is evident from her overactive Instagram feed, a platform she uses as a kind of frenetic note-taking, and as a way of feeling connected to a community when she’s logging untold hours alone in her studio.

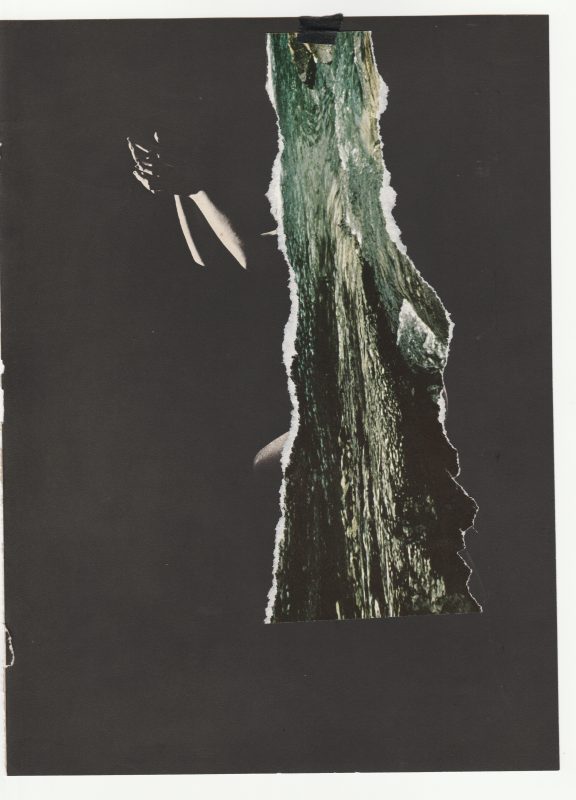

Meszaros first began appropriating photographic material in a series of collages, where bodies from John Everard’s Second Sitting: Another Artist’s Model (The Bodley Head, London, 1954) first appear, backdrops to natural elements ripped from the pages of National Geographic. New York, the mecca of printed matter, was among other things, a chance for Meszaros to expand her visual archive. After that fateful storm in NY, Meszaros found, in the bargain bin at the Strand, a copy of Velvet Eden (Metheun, New York, 1979). These two books, one an instructional manual for photographic lighting, the other a retrospective glance at a collection of photographic erotica became the foundation for two intertwined bodies of work.

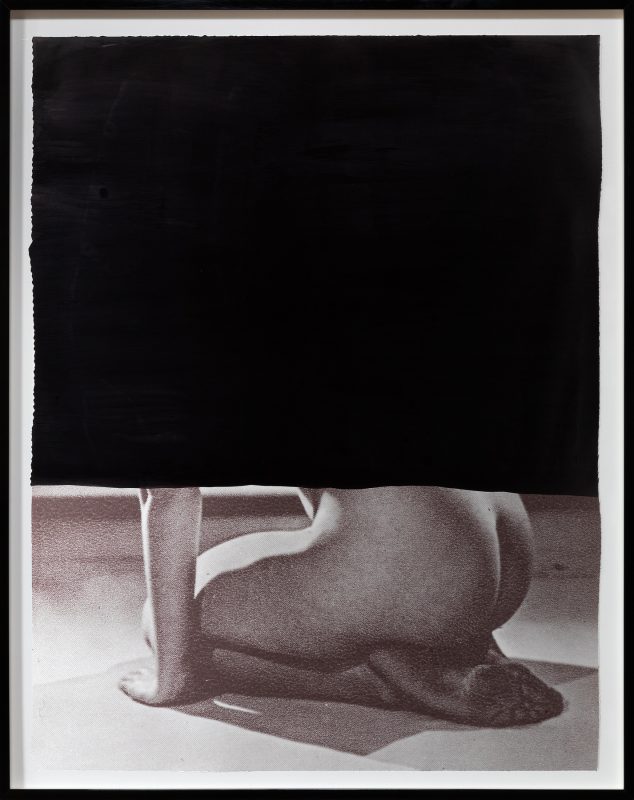

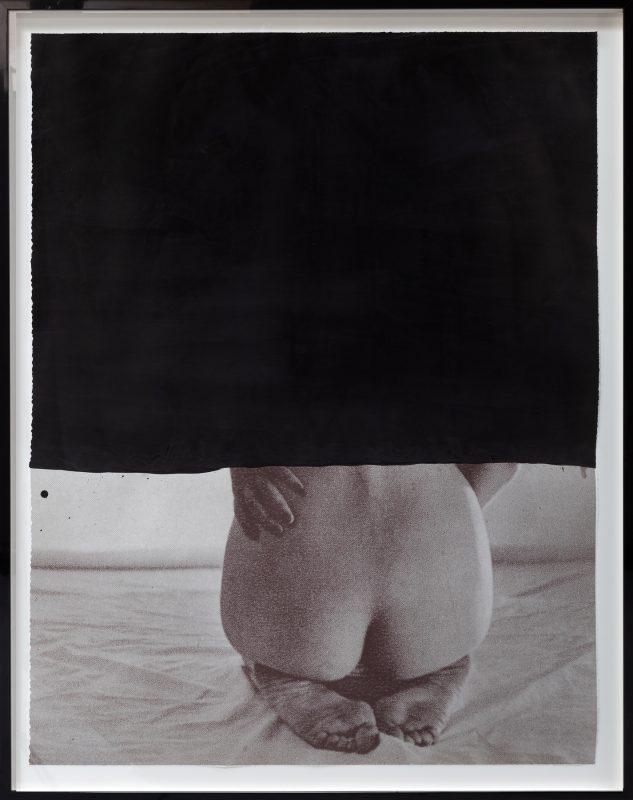

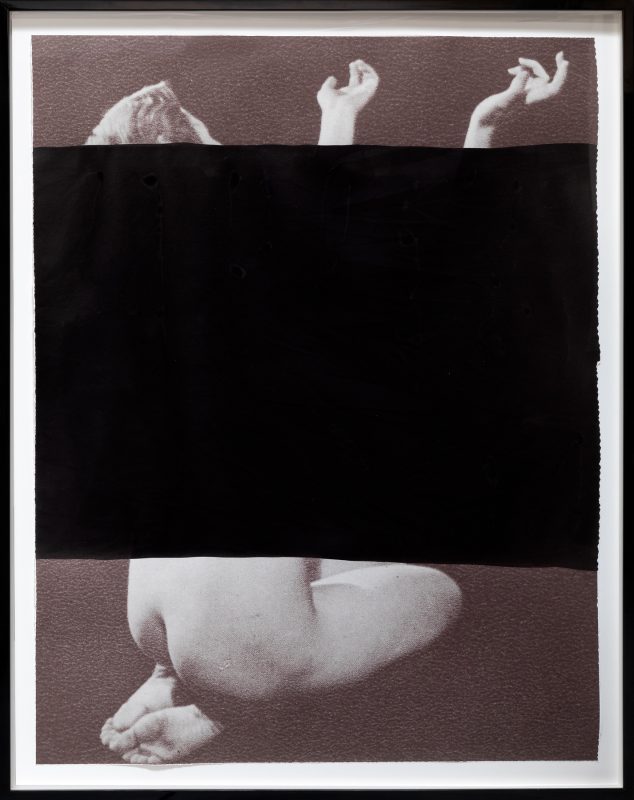

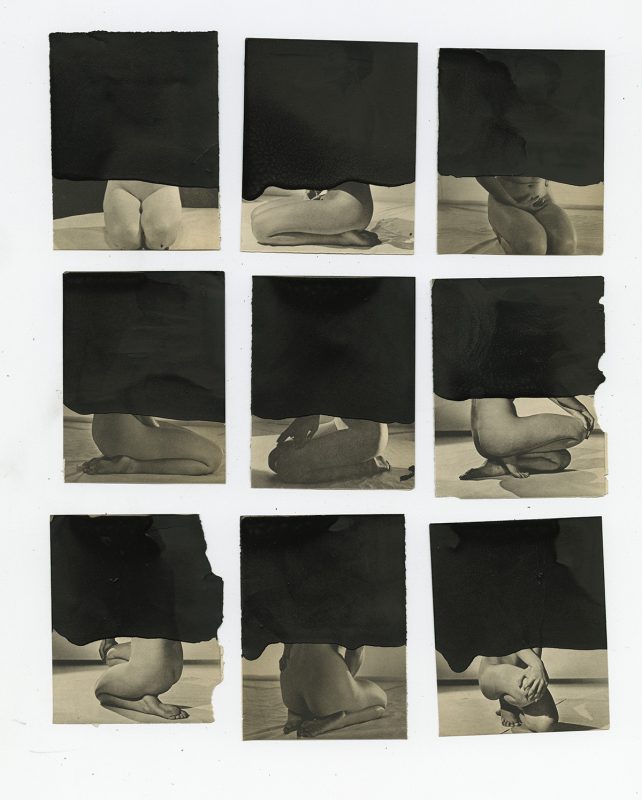

Intrigued by the bodies in Second Sitting, Meszaros began cutting up the contact sheet-like grids of images that punctuate various chapters. The images she appropriates all show women in kneeling positions – a posture at once awkward and submissive – their heads mostly angled to obscure their faces, their hands usually set demurely and strategically in their laps. For her series You’re damned if you don’t and you’re damned if you do, Meszaros made new pairs and grids, combining different models and exaggerating the strangeness of their repeated postures, then swept each one over, quickly, with a heavy black ink, a redaction of beauty and desire, and an invitation to look beneath the surface, where ghosted forms and faces reemerge, alchemically finding their way back to the light.

Once untethered from the page and released as pocket-sized cards, their currency changes: sequential instruction gives way to free-floating erotica. “For me,” Meszaros has said, “appropriating the images is a way to start to question their original intentions, and to slow down the reading of the images.” Meszaros eventually revisited the book a third time, and selected ten images to scan and enlarge. Scaled up to roughly life-sized, the singular images in Damned, each similarly redacted, offer a more forensic view of the originals – dirty feet and wrinkled sheets – as well a bodily relation to the viewer, whose own face might be reflected back in the blackness.

Meszaros used to make oversized charcoal drawings of animals, their heavy bodies unfurling down the lengths of long paper. Though never explicit, this imagery betrays latent power and basic instincts – primal, mythic, sexual. The muscled, bodily action of mark-making and the quickness of feeling out a shape or a line carry through to her newest work, though the scale and medium have drastically changed.

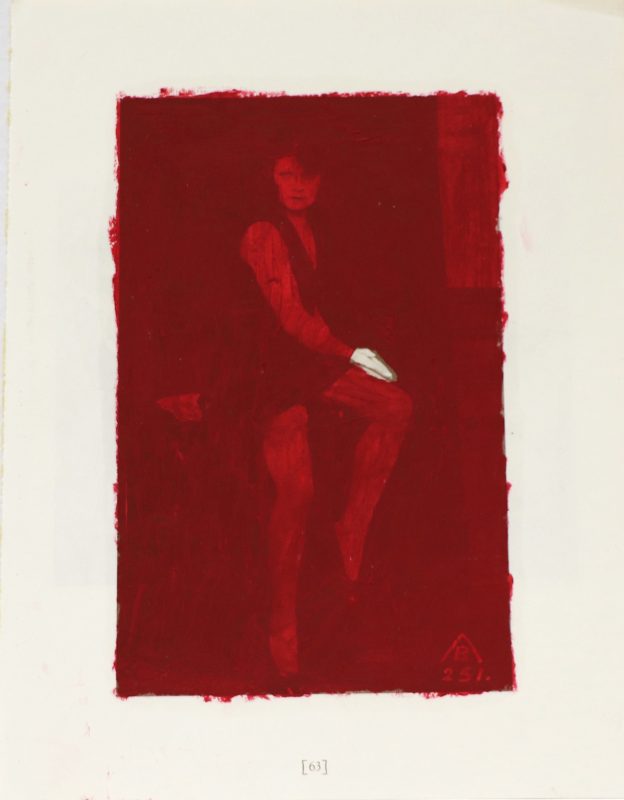

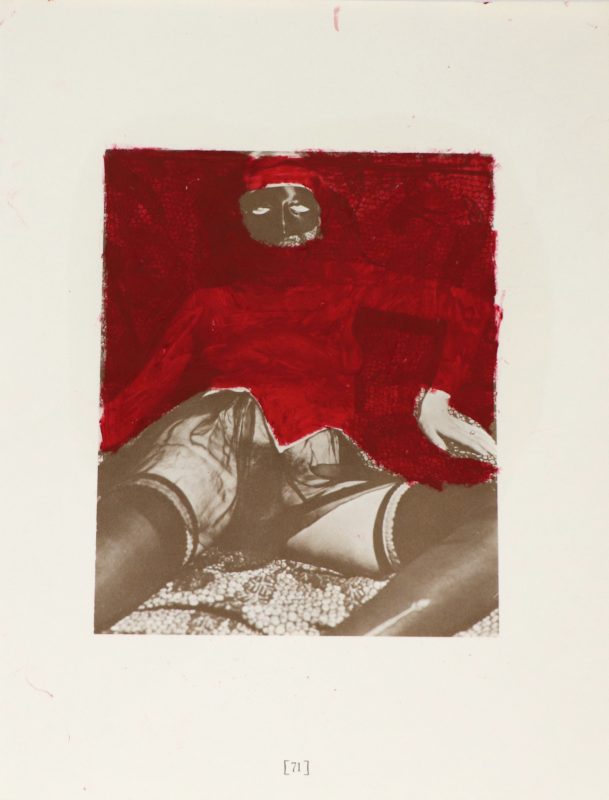

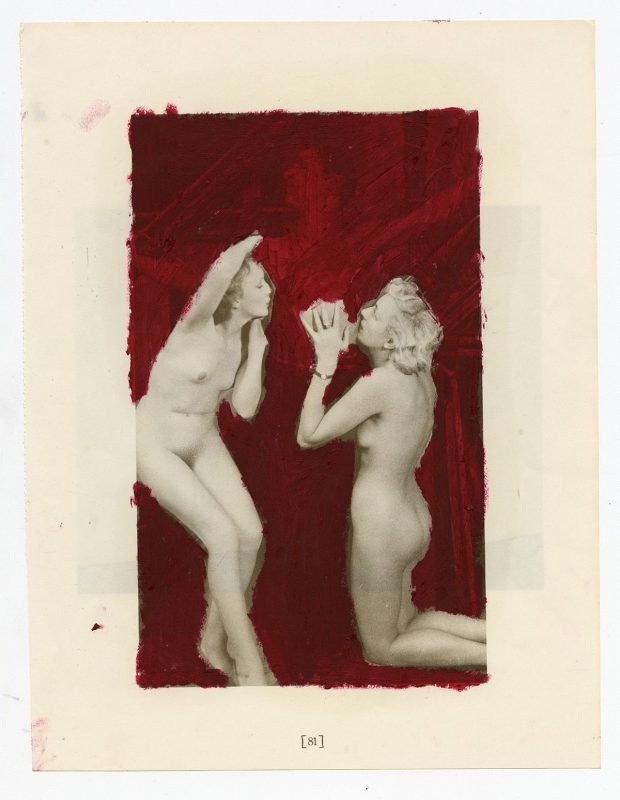

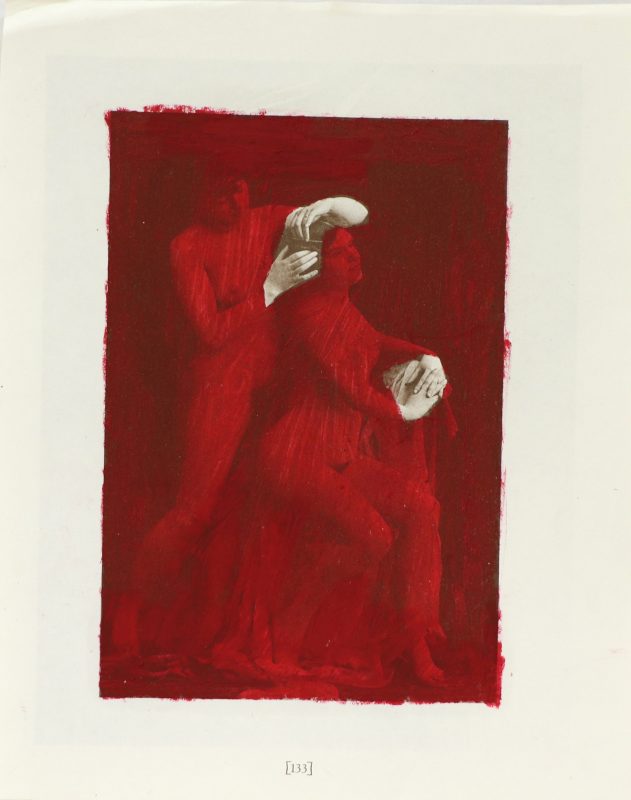

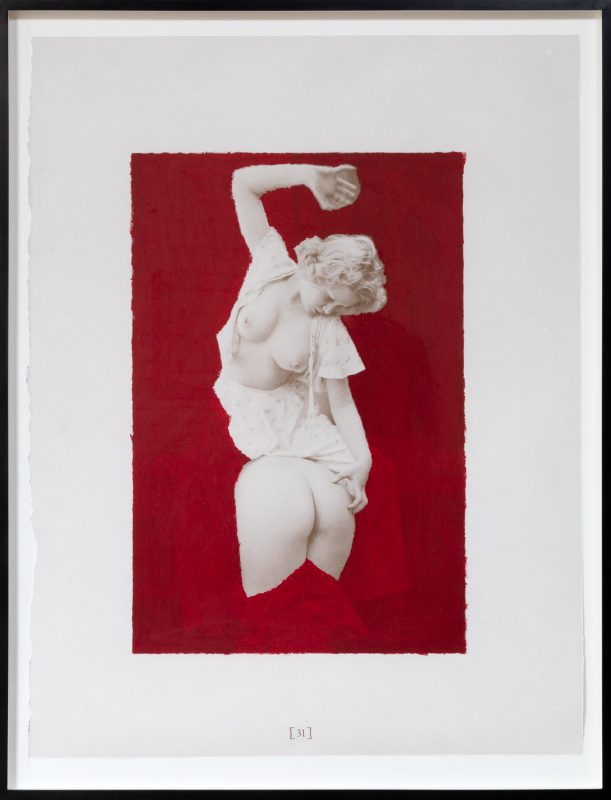

Her approach to the works in the series Strange Spot, drawn from the pages of Velvet Eden, is similar, though Meszaros has added a shock of colour. The softly textured fire-engine red pastel she pushes over each image evokes the luxuriousness of velvet and the red-light red-lipstick feel of forbidden desire. Though they span from the late nineteenth century to the 1950s, Meszaros’ choices and reworkings obscure their respective ages and marks them out as distinctly contemporary. If the kneeling women carry a certain burden in their stasis, the sitters here are active and often funny – involved in a different kind of performative collaboration. Most of the images would have been made originally as fodder for male desire. Yet the models appear in control of their gestures, perhaps enjoying their own moments of pleasure. Many of the scenes appear, from this distance, imbued with levity and humour: hands curled in comic claws, women nude but for wrist watches, as though keeping an eye on the clock of a work day before setting out to the rest of their lives.

Meszaros doesn’t speculate about what those lives might be or how we might value them – but her gestures recentre our attention to them, and to the idea that the women pictured in them were agents in their own worlds, just as we are agents in ours. The complexity of their positions – as objects of desire, as instructional tools, as icons, performers and storytellers – is difficult and, at times, uncomfortable. Meszaros’ works are as much reflections of our own anger and frustration with the power dynamics of gender and sexuality in the twenty-first century, as they are of our freedom to find ways of seeing that unsettle expectations and question desire. ♦

All images courtesy Corkin Gallery, Toronto. © Sondra Meszaros

—

Sara Knelman is an educator, curator and writer, and Director of Corkin Gallery, Toronto.

Captions:

1-Sondra Meszaros, Damned #1, 2019. Mixed media, digital pigment print on rag paper

2-Sondra Meszaros, Damned #7, 2019. Mixed media, digital pigment print on rag paper

3-Sondra Meszaros, Damned #10, 2019. Mixed media, digital pigment print on rag paper

4-Sondra Meszaros, You’re damned if you don’t and it’s damned if you do #17, 2019. Mixed media collage on found images

5-Sondra Meszaros, You’re damned if you don’t and it’s damned if you do, 2019. Mixed media collage on found images. Mixed media collage on found images

6-Sondra Meszaros, Bound #17, 2016. Mixed media on Stonehenge paper

7-Installation view of Sondra Meszaros: Two Blazing Glares, For Her Pierce 27 April – 1 September, 2019 at Corkin Gallery, Toronto. Image: Jimmy Limit

8-Installation view of Sondra Meszaros: Two Blazing Glares, For Her Pierce 27 April – 1 September, 2019 at Corkin Gallery, Toronto. Image: Jimmy Limit

9-Sondra Meszaros, Strange Spot #63, 2018 – 2019. Oil pastel on found book page

10-Sondra Meszaros, Strange Spot #71, 2018 – 2019. Oil pastel on found book page

11-Sondra Meszaros, Strange Spot #81, 2018 – 2019. Oil pastel on found book page

12-Sondra Meszaros, Strange Spot #133, 2018 – 2019. Oil pastel on found book page

13-Sondra Meszaros, Strange Spot #1, 2018 – 2019. Oil pastel on digital pigment print on rag paper