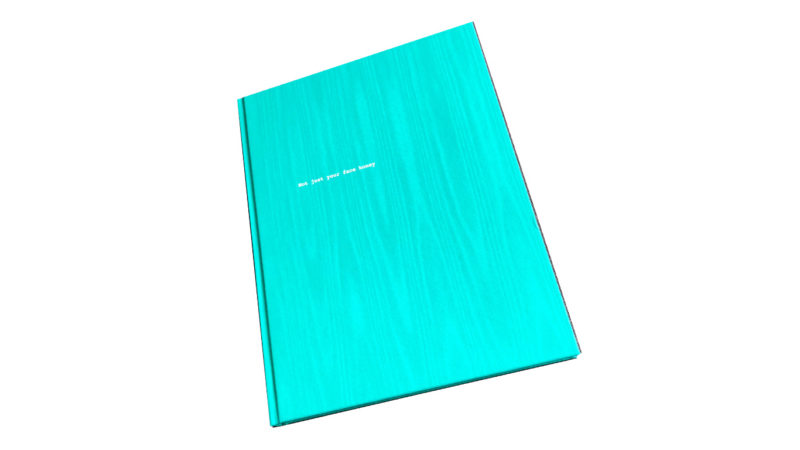

Stefanie Moshammer

Not just your face honey

Spector Books

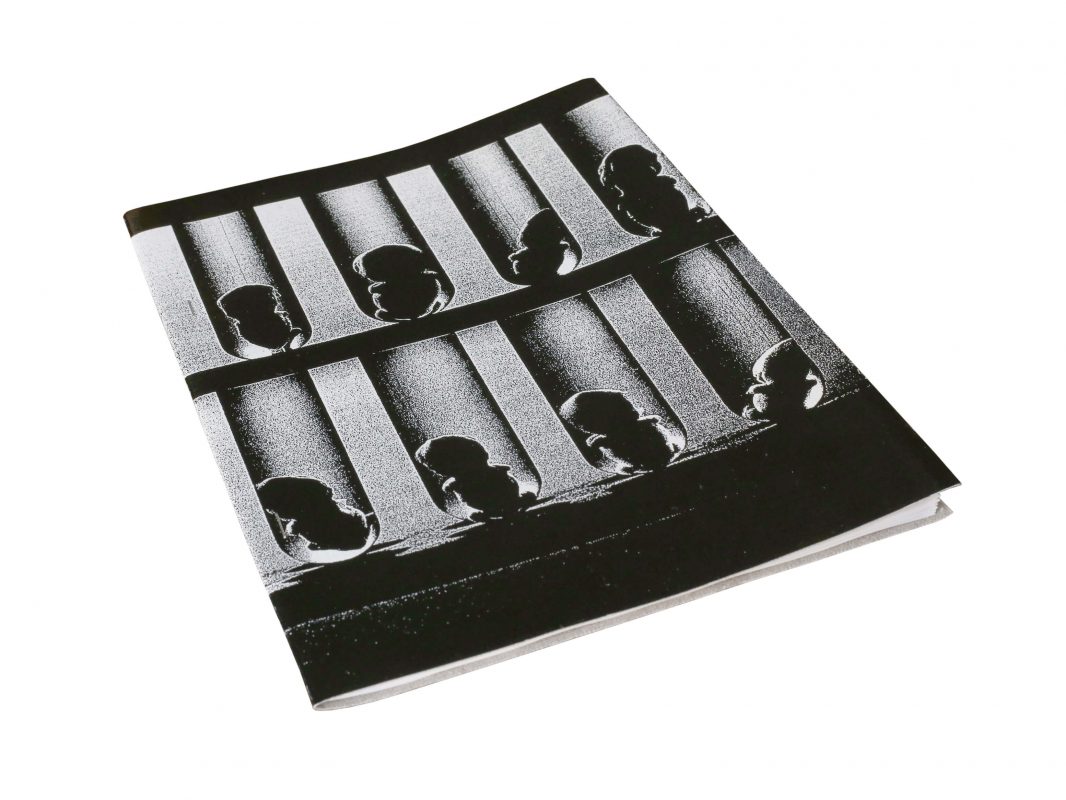

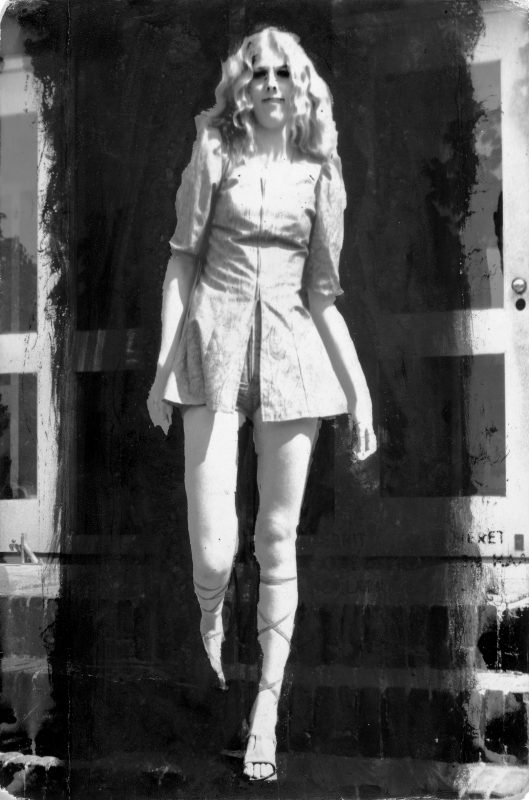

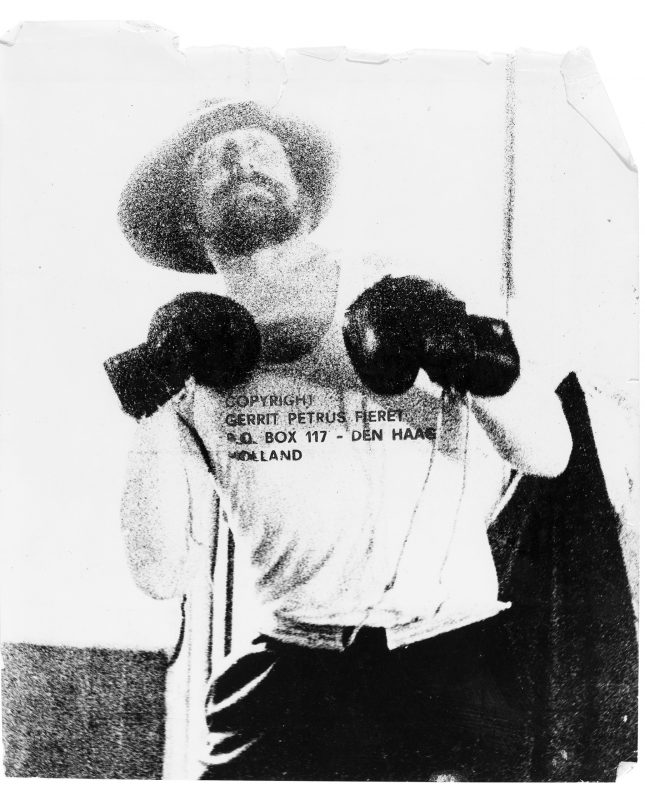

The American band LCD Soundsystem often sound a lot like Joy Division, or David Bowie, or The Fall, or innumerable other bands. But they also sound great, and unmistakably like themselves. Current C/O Berlin Talent awardee Stefanie Moshammer’s photo book Not just your face honey is also a lot like many other things. Like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, it starts with a letter, which may or may not be ‘epistolary fiction’. It matters not, because in either case the letter serves as an intriguing set up.

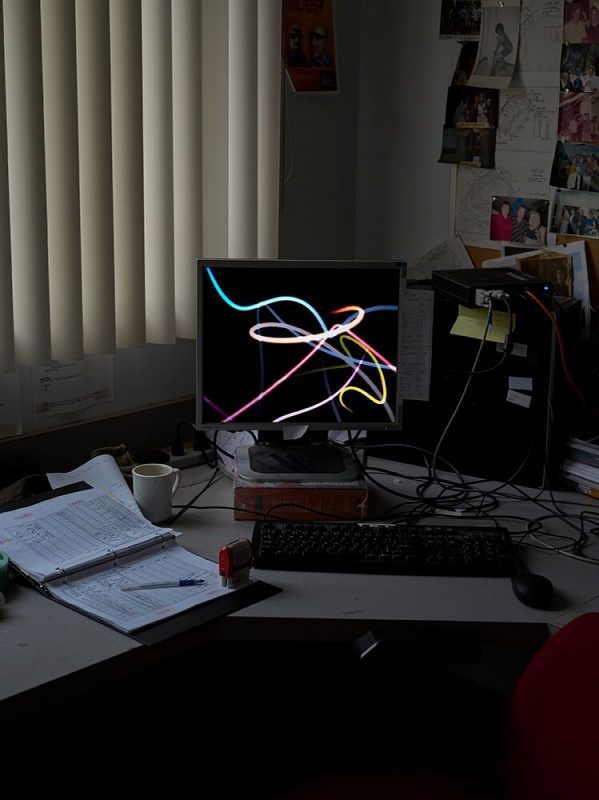

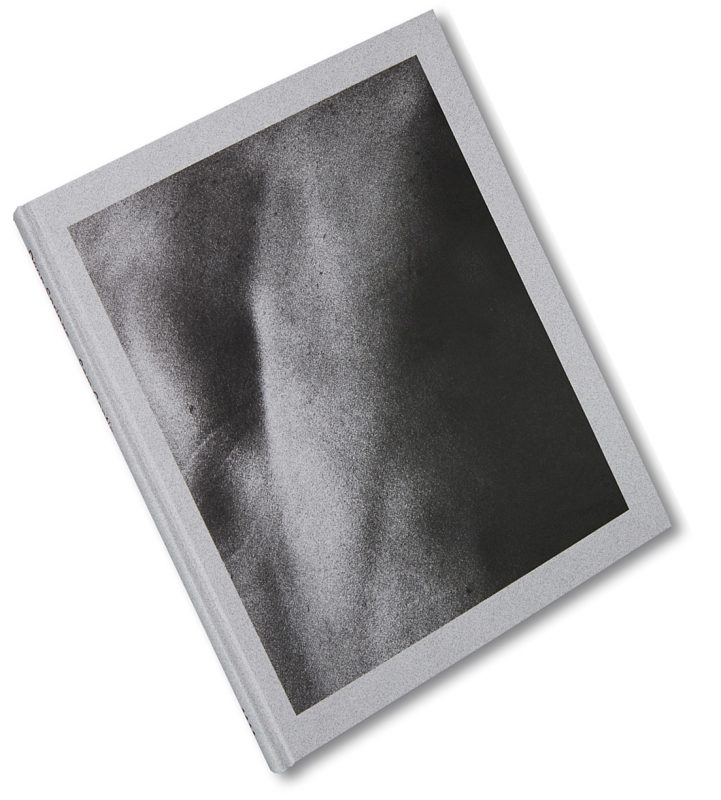

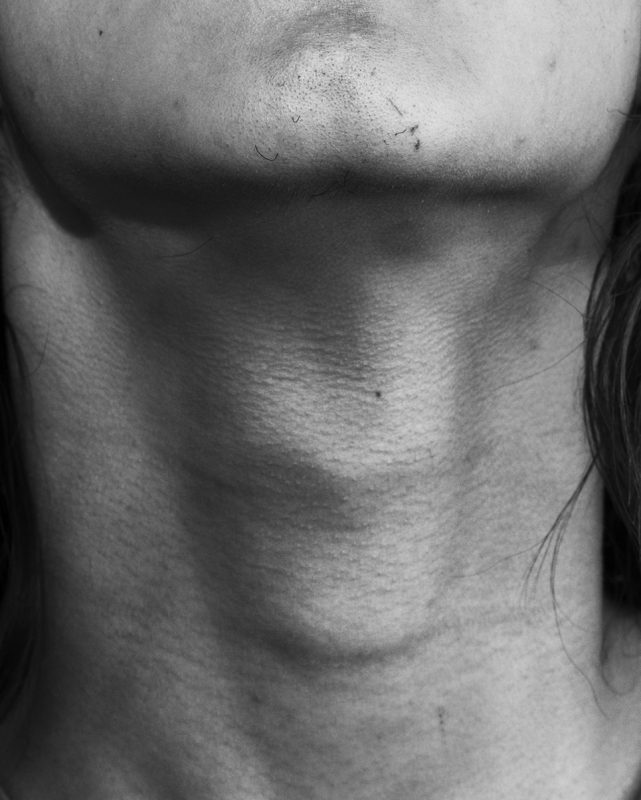

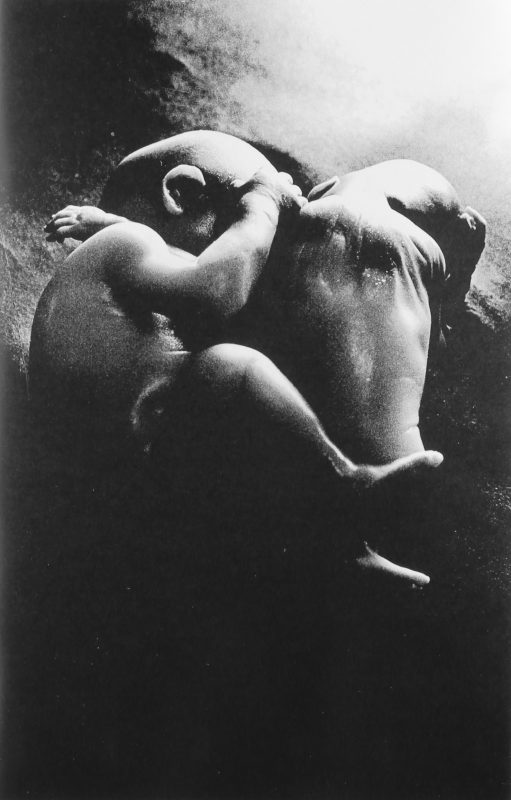

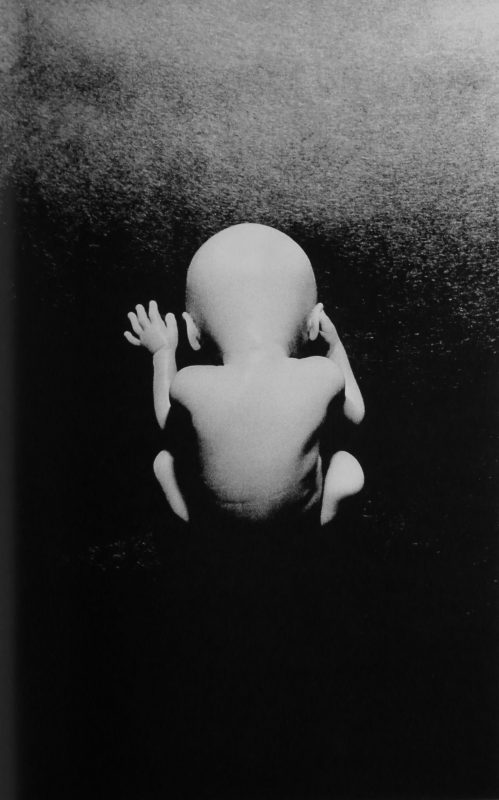

The rest of the book – a series of photographs which echo the text of the letter or symbolise related themes – is an edgy study of attraction and obsession, studded with strong sexual metaphors (such as a suggestively female kiwi fruit, an equally erotic orange, a cock-and-balls cactus and a giant cock rock). It is also – like the latest LCD Soundsystem album – about the death of the celebrity-obsessed American dream. This is subtly inferred throughout, but most memorably by a ripped tyre fragment in the dirt, its colour and shape mirroring a subsequent dead bald eagle, nailed to a mast. Figuration, direct reference, allusion, subtext, metaphor – this book has all the layered depth of a good novel, never mind a good photo book.

There’s something of Sophie Calle in all the surveillance and the stalking tendency. One or two cinematic pictures have a touch of the Gregory Crewdson aesthetic too. And in many ways – with its letter and a map introducing a warped love story told in both colour and monochrome, its road trip, telephones and tyre tracks, its mash-up of photographic styles, and its sprinkling with studio set pieces – it is more than a little like Christian Patterson’s Redheaded Peckerwood.

Smart and millennial, Moshammer’s mix-and-match art is deft in its lightness of execution. However, as it occasionally wears its influences a tad heavily, maybe it misses greatness with little lapses in idiosyncrasy. But this is a picky criticism: Not just your face honey is a deeply ambitious and generally very successful work by an early-career artist. If she continues with this much imagination, sophistication and skill, many more awards should follow. Talent indeed. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist and Spector Books. © Stefanie Moshammer