Aladin Borioli

Bannkörbe

Book review by Rica Cerbarano

Swiss artist Aladin Borioli advances his decade-long research project, Apian, with the latest work, Bannkörbe, now published by Spector Books. In his distinctive field, Borioli navigates a diverse landscape that blends anthropology, graphic design, and photography to illustrate a past beekeeping technology found in northern Germany. As Rica Cerbarano writes, this investigation into the relationship between humans and bees, delineates a symbiotic relationship that has sustained humankind for centuries – one that might offer critical explanations of our contemporary society.

Rica Cerbarano | Book review | 7 Mar 2024

In the field of visual studies, sequencing pre-existing images through the practice of montage is widely recognised as a means of knowledge production. Georges Didi-Huberman, speaking of Bertolt Brecht’s “Work Journal” in the essay The Eye of History – When Images Take Positions (2018), wrote that the writer and playwright ‘renounces the discursive, deductive and demonstrative value of exposition – where exposition means explaining, elucidating, telling in a sequential manner – in order to unfold more freely the iconic, tabular and displaying value.’ It’s precisely from this kind of neutral approach that Aladin Borioli’s Bannkörbe comes to life, resulting in a publication with Spector Books that is dedicated to the unusual artefacts of the Bannkörbe, a distinctive type of beekeeping technology prevalent in northern Germany during the period spanning the 16th and 19th centuries.

Here we have one of the many different shapes taken by the anthropological research carried out by the Swiss artist over the last 10 years. In fact, since 2014, Borioli has been working on a larger project called Apian, in which he explores – together with collaborators – the centuries-old relationship between bees and humans and how this interconnection can evolve and develop culturally. Communicated under the statement of a “self-proclaimed Ministry of Bees”, the idea behind the project is to create a political lab that investigates the role of bees in our society, confronting the failure of the political institutions in recognising the impact of bees on human beings. Harnessing his background in graphic design and photography with his studies in visual and media anthropology, Borioli devises a fluid, multimodal research method that gives him the freedom to experiment in the form of final outputs – be they a scientific article, book, video or sound piece.

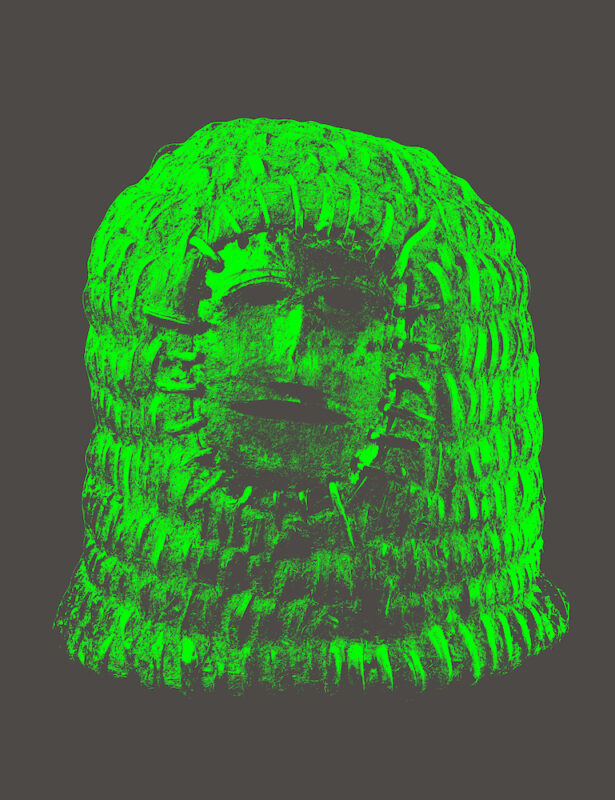

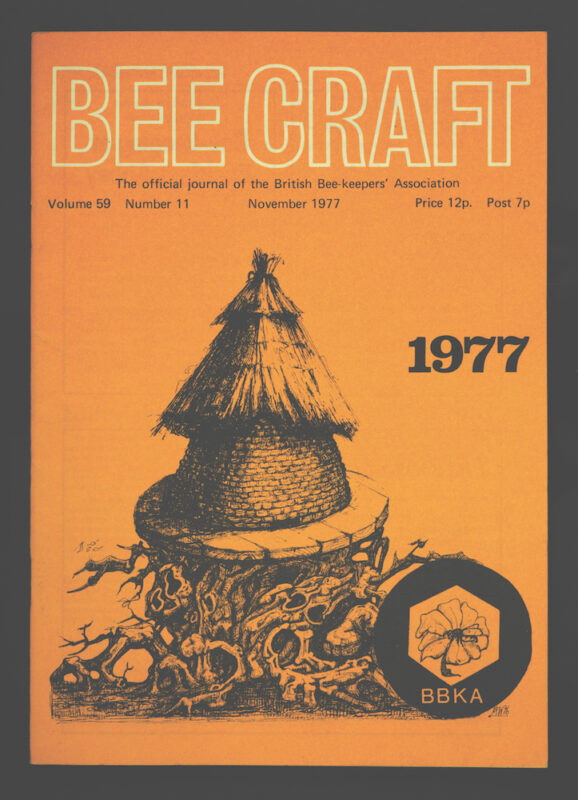

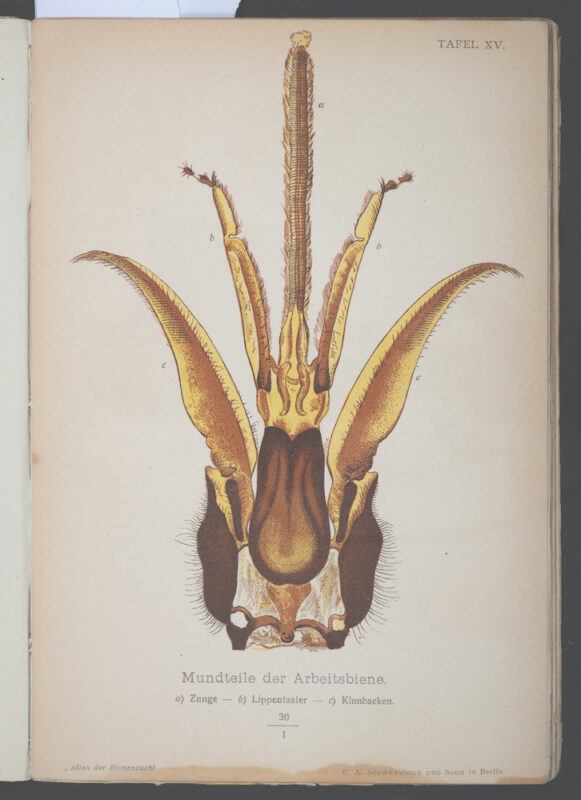

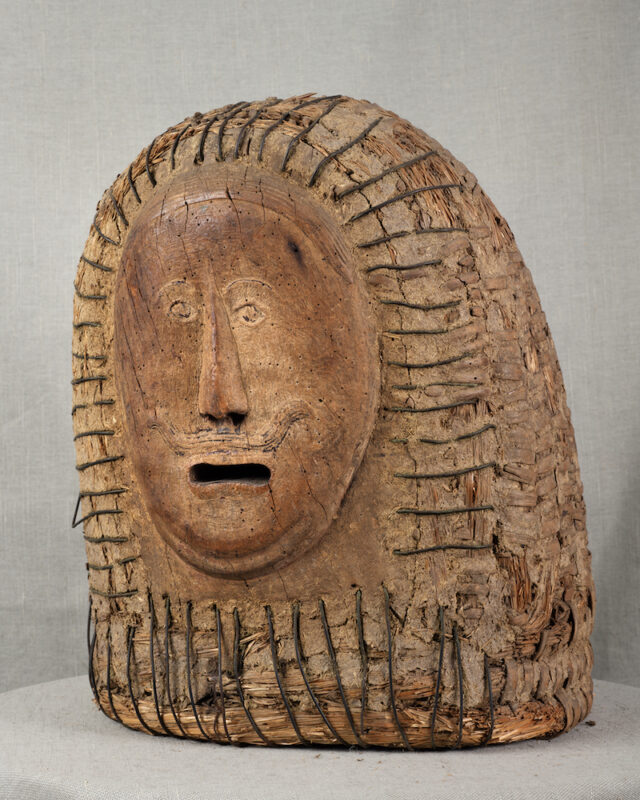

Unlike some previous artists working on the same theme (think Mark Thompson’s video performances in the 1970s and 80s), Borioli immerses himself into the background of the project, hiding his actions behind a collective and impartial conception of the study and disclosure of this subject. His imprint is visible in the theme and in the Warburg-like approach, however nothing about him transpires through from the 176 pages of the book, which is just in a larger format than his previous Hives, 2400 B.C.E. – 1852 C.E. (RVB Books and Images Vevey, 2020). This time, however, the subject narrows sharply to devote itself entirely to the human artefact of the Bannkörbe. These hives, a peculiar aspect of skep beekeeping, stand out due to their unique visual features – grotesque-looking wooden masks that ward off the evil eye. Today, in light of modern technologies and contemporary beekeeping practices, and given our ambivalent relationship with the animal species (oscillating between love and exploitation), the Bannkörbe have a symbolic presence: they represent a trace from the past of a technology that on the one hand was extremely anthropomorphic and anthropocentric, but on the other hand was constructed as a functional artefact to defend the bees, acting like scarecrows. By bringing together text, new images and archival material, Borioli builds a journey back in time in search of the visual connections that led to the spread, though exclusive, of this mysterious object that retains an apotropaic feeling.

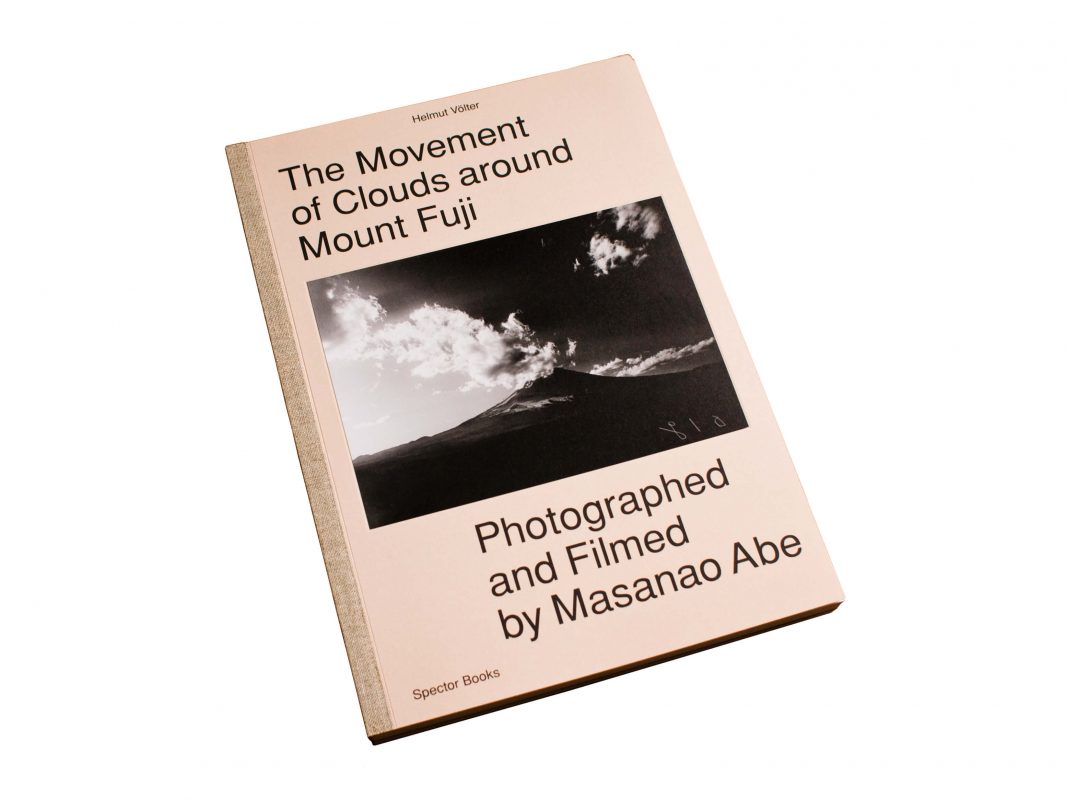

The investigation is developed in two parts: firstly, through archive images sifted through mostly books, and the other with new photographs taken by Borioli in local museums and private collections across Lower Saxony, Germany. The archival material gives us back a fragment of the extensive iconographic research that Borioli, intrigued by the grotesque forms of Bannkörbe, exercised. In search of a rather unknown history, Borioli started looking into its depth in order to make sense of what seemed to be an ancient tradition, whose design most likely dates back to c. 1540, with little historical documentation behind it. In fact, due to the use of delicate materials in hive construction, the scarcity of tangible historical evidence in the realm of beehive history is a real issue. Hence the whole practice of Borioli constitutes a way to, in art historian Hal Foster’s words from his essay, “An Archival Impulse”, ‘make historical information, often lost or displaced, physically present.’

The distinctive aspect of Bannkörbe lies in the visual manifestation of masks, which was precisely what led Borioli to trace the cultural origins beyond the realm of beekeeping. Moving between the domains of magic, beekeeping and grotesque aesthetics, he freely collected and composed a stream of images that shape, what Aby Warburg referred to as, the ‘paths taken by the mind’. In particular, the influence of these hives – at least in a visual sense – appear to originate from a specific type of eerie architecture known as mascarons. This form of stone face-shaped structure embellishes non-anthropomorphic architecture, with the idea that their magical qualities can repel malevolent spirits. While predominantly ornamental, some mascarons take on functional roles, like fountain forms whose mouths expel water, reminiscent of the most recognised feature of unsightly architecture: gargoyles. Bannkörbe beehives possess functionality too; their mouths serve as flight holes through which the bees come and go. Synonymously, they also serve as instruments of control and can pose a threat to bees, or being associated with brutal practices, where beekeepers resort to harmful methods that exterminate bees towards the end of the summer – a process aimed at easing harvest. This innate ambiguity leaves room for personal interpretation, or the simple realisation that there is no single point of view and that the relationships between species is first and foremost told from our partial perspectives as human beings.

In the middle of the book, 59 images printed on a different paper give us a glimpse of nearly all of the Bannkörbe left nowadays. While the archival research conveys the dynamic and fluid nature of Borioli’s inebriated and playful exploration, the serial aesthetic of these newly produced photographs leans towards a more “orthodox” scientific approach. Such a method adds a precious layer to the whole project as it brings the entire study back to the tangibility of the present as well as its ethnographic character.

What is staged by Borioli through the various channels in which this research takes shape (including the primary source of the project – the website) is a feedback loop approach that continues to generate visual associations and thematic links, guiding the unfamiliar reader to delve into the enduring relationship between humankind and bees, a very ancient phenomenon that lacks a comprehensive visual archive or the widespread representation it truly deserves. With this new book, Borioli continues his endeavour of combining multidisciplinary pieces of knowledge with the aim of generating other worlds, other connections, other stories. Conceiving his work as a trigger of ideas and artistic, scientific and philosophical interactions that transcend his presence, the artist aims at a horizontal broadening of engagement. Bannkörbe proves Borioli’s full and genuine dedication to a wider understanding of these interspecific relationships between humans and bees, once again shedding light on the intricate networks that have allowed humankind to exist for centuries.♦

All images courtesy the artist and Spector Books, Leipzig © Aladin Borioli

Aladin Borioli: Bannkörbe runs at C|O Berlin until 21 May 2024.

–

Rica Cerbarano is a curator, writer, editor and project coordinator specialising in photography. She writes regularly for Vogue Italia and Il Giornale dell’Arte, where she is the Co-Editor of the Photography section. She has also contributed to Camera Austria, Over Journal, Hapax Magazine and Sali & Tabacchi, amongst others. In 2017, Cerbarano co-founded Kublaiklan, a collective that has curated exhibitions at Images Vevey (Switzerland), Gibellina PhotoRoad (Sicily, Italy), Cortona On The Move (Italy) and Photoszene Festival (Cologne, Germany), amongst others. In 2022, she was a member of the Artistic Direction Committee at Photolux Festival (Lucca, Italy), where she curated Seiichi Furuya: Face to Face, 1978 – 1985 and Robin Schwartz: Amelia & the Animals.

Images:

1>4-Aladin Borioli, Bannkörbe book cover and page excerpts (Spector Books, 2024).

5-Aladin Borioli, Bannkörbe, 2023. Provenance: Bomann-Museum Celle, Germany.

6>9-Aladin Borioli, Bannkörbe, 2023. Provenance: Collection Hans-Günther Brockmann, Germany.

10-Aladin Borioli, Bannkörbe, 2023. Provenance: Institut für Bienenkunde Celle, Germany.

11-Aladin Borioli, Bannkörbe, 2023. Provenance: Museum Nienburg, Germany.

12-Aladin Borioli, Bannkörbe, 2023. Provenance: Heimatbund Museum Soltau, Germany