Michael Ackerman

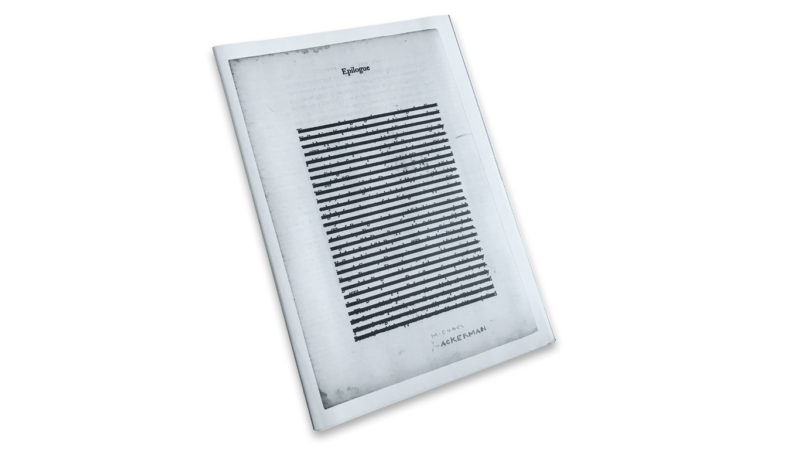

Hunger – Epilogue

Void

In 2005, I interviewed Oren Bloedow, co-songwriter and guitarist of Elysian Fields, the obscure and gloomy Brooklyn-based band he formed with ex-lover and sultry torch singer Jennifer Charles – I wrote about music before I came to photography. They had just released Bum Raps & Love Taps (2005), an album that dealt with personal pain, but also feelings of transcendence. “I believe that many of the challenges related to joy and sorrow have to do with clinging to moments, to time,” Bloedow told me. “When something starts to feel good, you tend to slow it down so that it doesn’t slip away. And when something feels bad, you do the same to prevent it from escalating.”

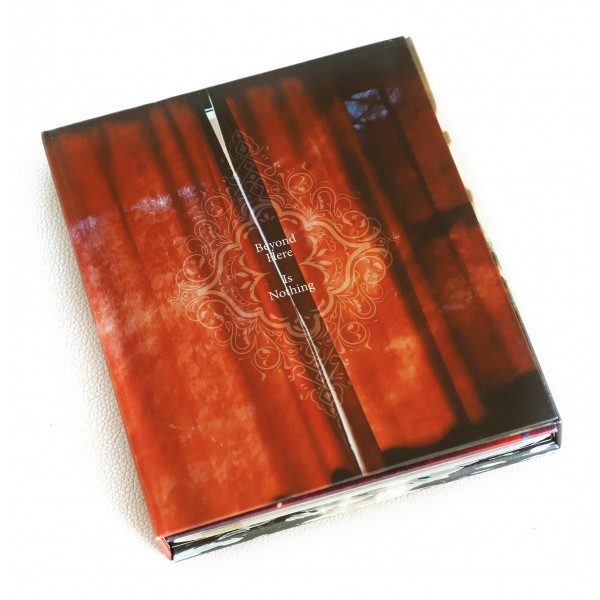

On the cover of the album is a black and white photograph of an old man having a cigarette, his face shrouded in smoke, with a pint glass on the table that could be perceived as half full or half empty. The photograph is by Michael Ackerman, and it is also printed in Hunger – Epilogue, the first publication of Ackerman’s work since his highly-praised book Half Life (2010). With over 130 photographs, half of them previously unseen, the large-format newsprint is a fitting end to Void’s Hunger series, a project that takes its lead from Franz Kafka’s short story A Hunger Artist (1922).

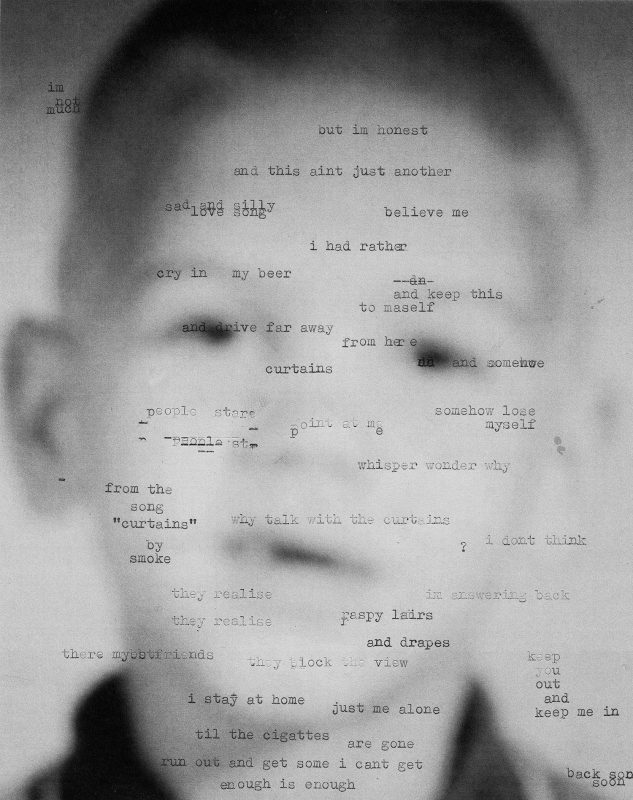

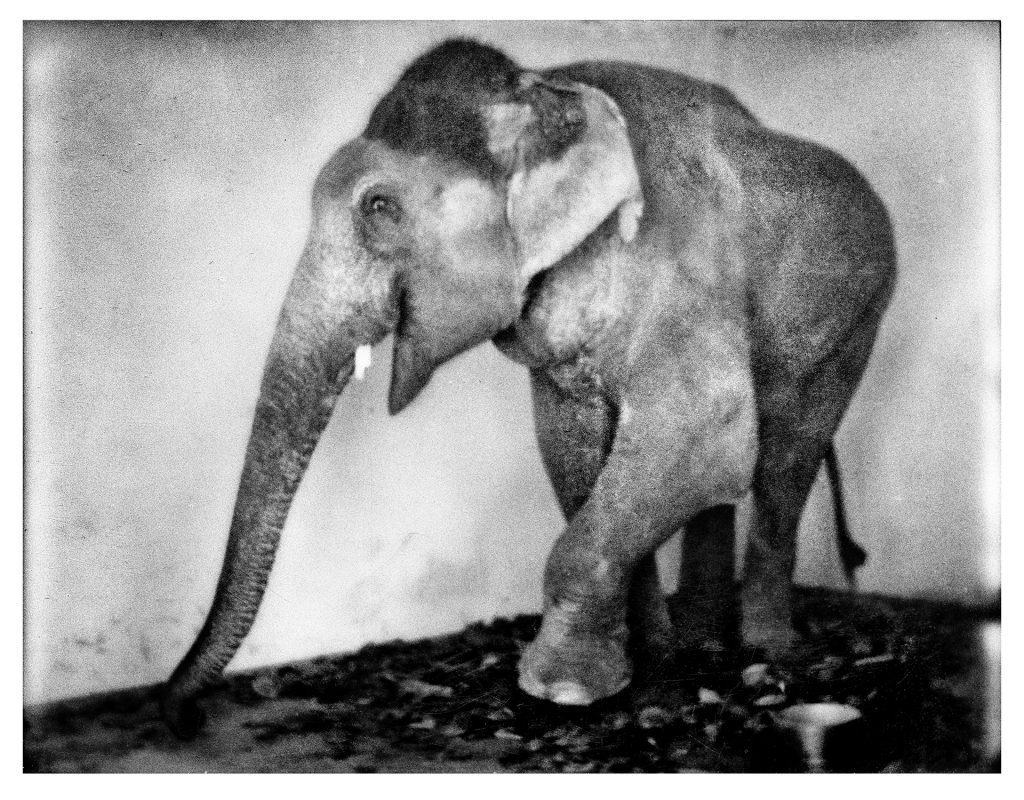

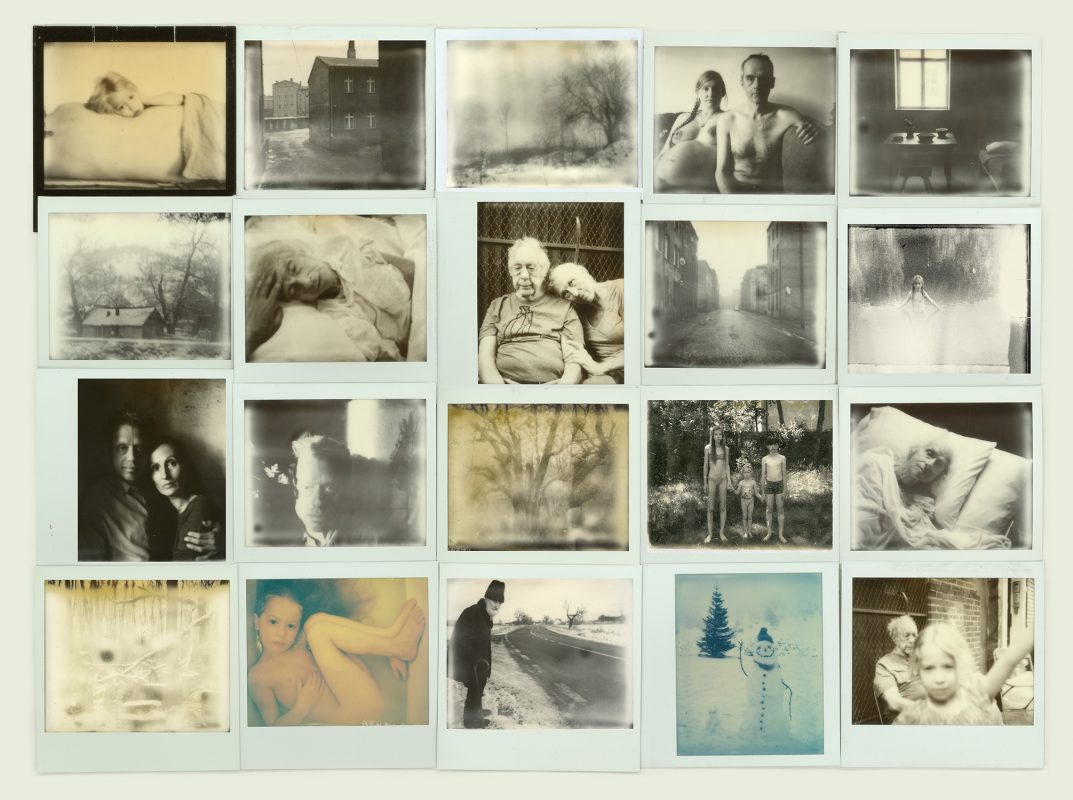

‘Time, in its great disarray, is a specialty of Michael A’, writes friend and filmmaker Jem Cohen. Ackerman himself has confessed to his obsession with the passing of time. Many of his photographs show traces of fading and erasure, others suffer from marks, scratches or light leaks. There are vivid vignettes of life, friendship and love, as well as the fear of losing loved ones. Dark and ghostly portraits carry an intensity or a fragility, or both at once. A walled-in elephant looks ecstatic, vultures feast on a carcass. There’s anguish. One spread really kicks the gut: a constellation of re-photographed portraits from tombstones and official reports; mostly children, mostly from the Holocaust (yes, that is Anne Frank there) – death and remembrance are as much a personal as they are a collective experience. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist and VOID. © Michael Ackerman