Stephen Gill

Coming up for Air

Exhibition review by Jesse Alexander

On the occasion of Stephen Gill’s retrospective at Arnolfini, Jesse Alexander highlights how the artist’s varied and prodigious output from the last 30 years has been underpinned by restless experimentation and a rich sense of place.

Despite subtle signage suggesting that visitors start their visit to Stephen Gill’s extensive retrospective Coming up for Air at Arnolfini, Bristol on the gallery’s first floor, most visitors will begin at ground level, chronologically reversed, and enjoy the Bristol-born photographer’s more recent works. The ground floor gallery is dominated by Night Procession (2014–17), The Pillar (2015–19) and the more recent series Please Notify the Sun (2020), which was completed during the lockdown. The repeated views from a trap camera installed in a field near his home in Sweden that comprise The Pillar have been published widely, and at varying scales. Yet this installation is the largest display of prints from the series (first published in book form in 2019) and the linear arrangement in the gallery accentuates the flat, expansive topography of this view as well as the cadence amidst the series’ repetition. With the focus set to infinity, the background is always sharp, giving a sense of these creatures’ enchanting, temporary presence, but also perhaps hint at the birds’ own appreciation of the backdrop to the stage on which they perform. In those where the birds have their backs to the camera, they take on the role of the Romantic Rückenfigur, contemplating the meaning of the scene that unfolds before them. It’s hard not to anthropomorphise the birds’ myriad startled expressions and clumsiness or, on other occasions, to simply be in sheer awe of their spectacular elegance.

Where The Pillar gives an impression of place in the sense of its broad surface features, Night Procession, also made with a trap camera, pulls us right down into the floor of the forest, even incorporating mud and plant pigments in the printing process. Adjoining this space is an additional projection of this work: the duplication of images might be unnecessary, and Gill’s original collotypes are no doubt delightful objects, but the luminosity of these nocturnal images projected, all the while accompanied by the braying chant of Ada Gill’s cello, is evocative without being melodramatic.

Although in fact the outcome of a meticulous and diligent strategy, The Pillar and the infra-red flashed fauna in Night Procession typifies the low-fi aesthetics that are often associated with Gill’s work. Upstairs however, where the exhibition ‘starts’, we are reminded of Gill’s precocious technical accomplishment with photography (it’s a little like seeing early Picassos and being reminded at his draftsmanship before he turned to abstraction). The exhibition retrospective is accompanied by a publication bearing the same name of the exhibition but has even more images and fewer words to introduce discrete bodies of work (although there is an essay by the Arnolfini’s director, Gary Topp). Gill acquired technical skills early; his photographs from his teens and his twenties – from his travels and his observations closer to home – have a confidence and effortlessness to them that exceeded his years (it is also worth noting that, unlike the majority of his contemporaries who studied art and design at under- and postgraduate level, he completed a foundation course at college before working in industry). Gill’s raw skill as a photographer is perhaps most apparent in his portraits; the passengers he systematically photographed in Day Trippers (2001), the Gallery Wardens (2003) and the (mostly) older women in Trolley Portraits (2000–03) all seem to have been offered a space in which to present themselves authentically to Gill’s lens, entirely of their own volition, and seem to exude a sense of thoughtfulness and nobility.

Despite his ability as a portraitist, Gill is perhaps more associated with the representation of place (the exhibition is programmed as part of the Bristol Photo Festival 2021, the theme of which is a sense of place). Perhaps some of the least visually striking, yet most amusing works are his Billboards (2002–04) and Birds (2005–10). As with many of his series, these were the products of a strict strategy, and in these the result being a discordant relationship between the final image and text: Billboards shows us the backside of advertising hoardings, and often there is a contrast between the seductive strapline that titles the images, such as L’Oréal Paris. Because you’re worth it, and the grotty corner of some indistinct city periphery, shot with New Topographic-esque deadpan objectivity.

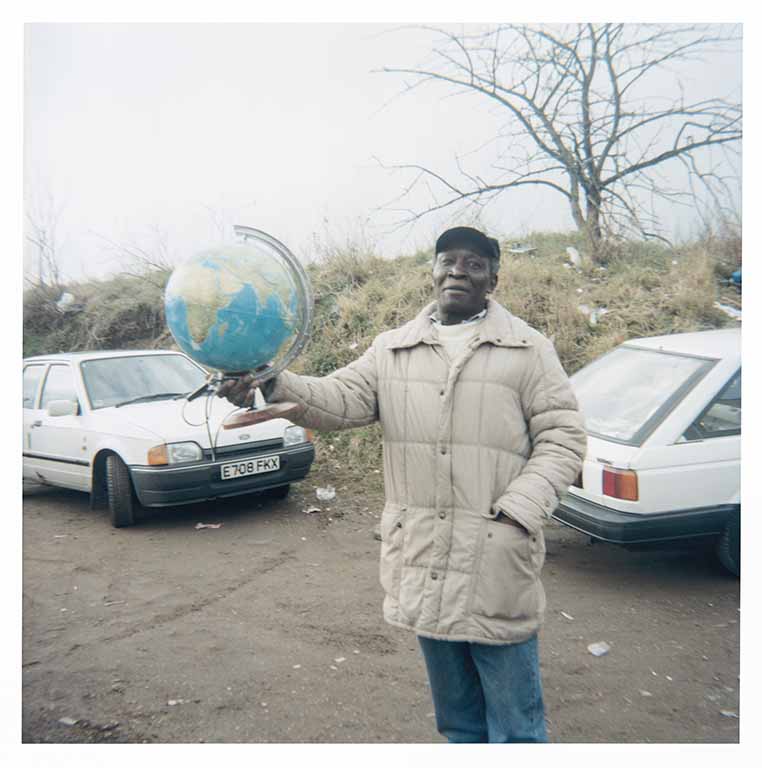

Consumption also features heavily in Gill’s seminal work from the period, Hackney Wick (2003–05), an affectionate essay dominated with flea markets, completed – legendarily – on a camera purchased there for fifty pence. This period and this body of work appear to have liberated Gill from received documentary aesthetics of the time and catalysed an increasingly experimental, exuberant approach in his practice. The abundance of, for want of a better word, ‘stuff’ that we see in Hackney Wick mirrors Gill’s own preoccupation with found objects and their potential for meaning.

Gill has incorporated found objects from an area into the final images in visually dynamic ways, including Hackney Flowers (2004–07), which are a kind of photocollage with objects laid on top of photographs, and Talking to Ants (2009–13), where objects were placed inside the camera, simultaneously obfuscating and embellishing views. Cabinets in the exhibition present some of these ‘primary sources’ – some of which are as ephemeral as drinks-can ring-pulls – and these further enhance the sense of reverence for the place and his subject.

Other projects have focused more specifically on found objects, such as his pictures of rocks and bricks used as missiles during the London riots in Off Ground (2011) and the folded, torn and otherwise frustration-wrought fruitless betting slips he found discarded on the street near his home in A Series of Disappointments (2007). This merging of place and artefact is also explored in Buried (2005–06) which involved burying prints, allowing the soil and ground to react unpredictably with the chemistry in the paper. This curiosity in the alchemical nature of the medium is also evident in Best Before End (2013), where Gill experimented with the effect of energy drinks, controversially marketed towards teenagers, on photographs, revealing their chemical potency.

In addition to the cabinets, the main upstairs gallery features the staggering number of Gill’s photobooks, almost exclusively published by himself. These aren’t ‘on display’ as such, nor are they presented in a traditional kind of ‘further reading’ area, but on a distinctive freestanding shelving unit. Perhaps it is the unimposing jaunty angles of the shelves, or the unfinished wood, which makes handling these remarkable pieces feel like a genuinely welcomed aspect of the experience of the show, and perhaps a less intimidating activity than it might otherwise feel like.

There is a certain radiance in Gill’s practice. It is distinctly playful; belligerent without being aggressive or stifled in self-assured irony. Maybe there is a youthfulness in his determination to persevere with a self-imposed strategy, or one of his many dilatory methods: an unstoppable belief that a project will, sooner or later, inevitably come together. But politics runs quietly through the veins of Gill’s work and, moreover, his willingness to embrace the aleatoric and to abrogate responsibility for substantial aspects of creative processes are admirable characteristics. Whilst I’m reluctant to draw things to a close with an often-cited remark about Gill, his output is astonishing. There is a huge amount of highly accomplished work in the exhibition, without becoming overwhelming, and also in the six hundred odd-page accompanying monograph. There is much more that could have been shown, but there is a lot more to come.♦

All images courtesy the artist and Arnolfini, Bristol © Stephen Gill

Installation views of Coming up for Air at Arnolfini, Bristol from 16 October 2021 – 16 January 2022, part of Bristol Photo Festival 2021. Photographs by Lisa Whiting.

—

Jesse Alexander studied at the Surrey Institute of Art & Design, Farnham, and the University of Wales Newport, and is a photographer, writer on photography and lecturer based in Somerset. His writing and projects are primarily concerned with landscape and the representation of place, and he is the author of Perspectives on Place: Theory & Practice in Landscape Photography (2015). He is currently Course Leader for MA Photography at Falmouth University.

Images:

1>2-Installation view of Coming up for Air at Arnolfini, Bristol, 2021. Photograph by Lisa Whiting.

3>4-From The Pillar 2015–19.

5>6-From Night Procession 2014–17.

7-From Pigeons 2012.

8>9-From Talking to Ants 2009–13.

10-From Hackney Flowers 2004–07.

11>12-From Hackney Wick 2001–05.