Iris Sikking

Guest Curator of Kraków Photomonth 2018

Amsterdam

Guest Curator of Krakow Photomonth 2018, Iris Sikking, shares her experience of organising the main artistic programme at this year’s edition, and her thoughts on whether festivals should eagerly promote themselves as “a place to celebrate photography,” as told to writer Taco Hidde Bakker. Their discussion also includes reflections on Sikking’s broad practice in the overlapping fields of photography, film, installation art and new media; the defining project in her career, Poppy – Trails of Afghan Heroin by Antoinette de Jong and Robert Knoth; and the importance she places on seeking out new practices embracing experimentation, and artists who use a variety of visual and narrative strategies to engage in in-depth and original research.

Taco Hidde Bakker: Iris, within the past two decades you have developed a broad and varied practice in the overlapping fields of photography, film, installation art and new media – with a particular focus on documentary and innovative means of storytelling. Your activities include, or have included, film editing, project management, research, teaching, writing and curating. From 2007 until 2010 we were both involved in the production of the multi-platform project The Last Days of Shishmaref, including a feature-length documentary film by Jan Louter and a series of photographs by Dana Lixenberg, which resulted in a book, exhibition, website and web documentary. Whilst I focused mostly on (image) research and writing, you were responsible for the project management. You continued working on other projects for Paradox, the producer of documentary projects addressing social issues with innovative ways of research and exhibiting, up until five years ago at which point you decided to take the plunge and develop a freelance curatorial practice besides your teaching activities. After you guest-curated two exhibitions at FOMU, Antwerp (Jeffrey Silverthorne and Yann Mingard, both in 2015), you have reached a new high point in your career this year with the curatorial appointment for the 16th edition of the Kraków Photomonth, Poland. Could you first tell me a few things about your development as curator and your curatorial approach.

Iris Sikking: After I graduated from the Academy for Film and Television in Amsterdam in the early 1990s, I mainly worked as a film editor, but some years later I was fed up with the lack of visual power in the films I was editing. I knew that the imagery could tell more so I felt the urge to learn more about the language of images, and their ability to communicate a meaning more generally. So I decided to study at the then freshly-founded MA programme in Photographic Studies, Leiden University in 2003. I co-wrote my thesis with Hedy van Erp about the depiction of the baby in photographic history, from amateur to professional photographs, and from marketing to ultrasound images. We then developed our thesis into the exhibition BABY – Picturing the Ideal Human, which was shown at the Nederlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam (2008) and the National Media Museum, Bradford (2009). Later, at Paradox I also worked as a curator on the sizeable projects, ANGRY – Young and Radical (2011), which offered a selection of thirty-five international artists, and quickly followed by what I call a defining project in my career, Poppy – Trails of Afghan Heroin by Antoinette de Jong & Robert Knoth, a book published in 2012, also materialising in an accompanying exhibition that has been travelling since. Poppy– Trails of Afghan Heroin was pivotal because it brought me back to film-making and reminded me of the power of editing, whilst serving as an introduction to the filmography of Adam Curtis and Johan Grimonprez. Narrative is an integral tool in their films, something I often miss in projects exclusively based on the still image.

My work at Paradox was an extraordinary learning experience from which I am still growing from – a demanding but rewarding seven years. Due to the fact that I could work within a set context for such an extended period of time, I was able to learn about every nook and cranny of the curatorial process, from fundraising to the necessity of debate around a given topic and project with experts on the subject matter. Besides, I have always undertaken many side activities, such as portfolio reviewing and visiting exhibitions both nationally and internationally. My long-term investment in building an extensive network that started during my involvement with Paradox, laid solid foundations for my recent curatorial activities. And working with people and on projects which you fully believe in pays off in the long run.

Through my collaboration with Yann Mingard, that I mentioned earlier, I came to know Lars Willumeit, who had contributed an essay to Mingard’s book, and who was also the Guest Curator for Kraków Photomonth 2016. Inspired by a conference I had co-organised in Amsterdam exploring digital forms of storytelling, Willumeit asked me to participate in his 2016 edition, for which I organised the group show A New Display: Visual Storytelling at the Crossroads.

THB: How did you interpret the commission for the 2018 edition? Were you given free reign in how you would approach the curatorial task and how you would develop a theme?

IS: Yes, I was given the freedom to curate and exhibit what I found important – a freedom, which, at the same time, I thought was slightly frightening considering the strong festival iterations of the preceding years. But having been given the freedom, and considering the impressive past editions, I felt at home with a festival whose organisers are not afraid of hosting topical exhibitions which engender debate. At several points during the development of my programme, the production team in Kraków suspected this edition might become the most political to date, which confirmed that I was on the right track. Especially the projects dealing with migration brought up issues that are highly controversial in Poland and not easily made discussable. Like many other European countries, Poland tries to keep its borders closed, while the value and contribution of immigrants is underestimated and seen as a threat, but like someone in Poland told me, their country is also made up of a cocktail of people of various roots and identities.

Environmental issues, and the difficulties of visualising them, formed another theme for this year’s edition. The city of Kraków, for example, suffers from intense air pollution between October and April. It made me sick and I couldn’t fathom what was going on with how I perceived Poland, which otherwise seems a prosperous country. People told me it wasn’t caused so much by the many coal-pits in the vicinity but by the extremely outworn fleet of cars and the traffic artery that is Kraków, an important city in Poland. Secondly, a key factor is the fact that many people still fire coal stoves and literally burn everything at hand, including plastics. Although this happens mostly in the surrounding villages, the smog blankets Kraków given that it is situated in a valley. The health consequences of pollution have only recently become public discussion points while there is scientific data available detailing which illnesses and deaths are correlated to these types of air pollution. The flow of data and its consequences, the third significant theme of the festival, was a hint to the financial crisis that began a decade ago. I chose this trio of themes because it touches on urgent matters: migration and politics, nature and care for the environment, data and its implications for privacy, as well as the financial crisis.

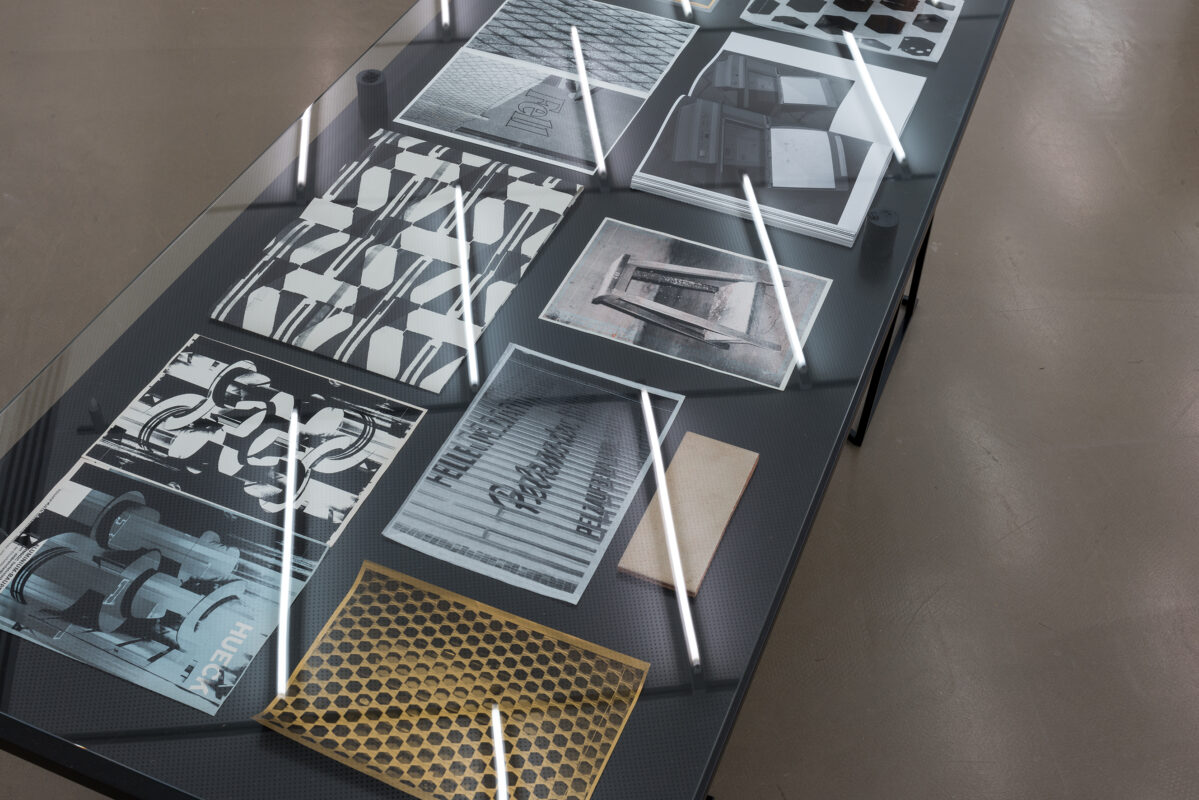

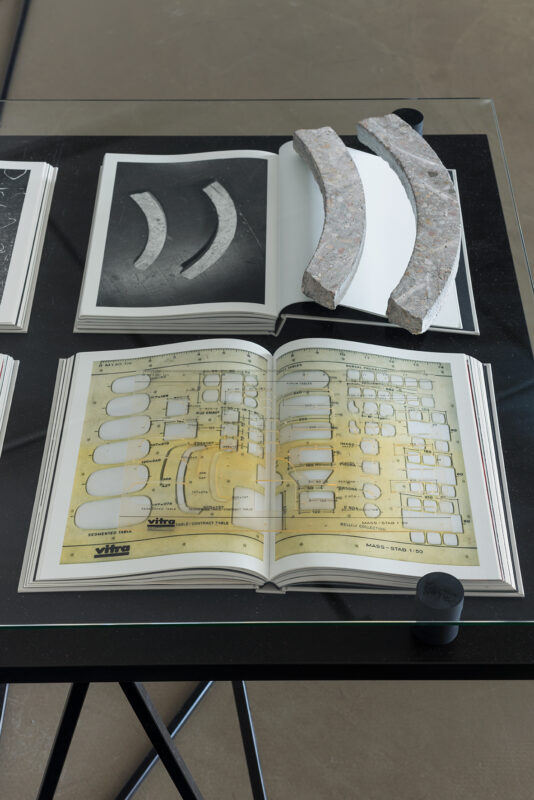

THB: Your theme for the festival’s main programme, titled Space of Flows: Framing an Unseen Reality, is ambitious and wide-ranging. You ask for the visitor’s patience and perseverance, as quite a few projects included extensive documentation and other contextual materials. I took one working day to visit the group and solo exhibitions comprising Space of Flows, spread across eleven museums and gallery spaces in the old town and neighbouring areas, including projects by no less than twenty-two artists and artist duos. Were I to study everything more closely, it would have taken at least two days. While I found the walks between the venues and the variety of mediums (film, photography, text, computers in either immersive settings or classical exhibition lay-out) to be highly-refreshing, I left with the aftertaste that the amount of information, storylines and variety of documentary approaches is impossible to fathom, perhaps even within the scope of a few days. What is this ‘space of flows’ and how did you use this idea to give shape to your set-up of the festival?

IS: I started from the concept of the ‘space of flows’, which I found fascinating during my reading, many years ago, of The Rise of the Network Society (1996) by Spanish sociologist Manual Castells. In a tempting way, he described the type of society that we were heading for in the 1990s. ‘The space of flows,’ he wrote, ‘is made up of movement that brings distant elements – things and people – into an interrelationship that is characterised today by being continuous and in real time.’ Virtuality has become visible in the networked society, so that we no longer live in a ‘space of places’ alone. This latter space, Castells explains, is the space where we know every corner, and in which we are acquainted with all our neighbours. The digital turn added a new layer, a ‘space of flows’ that catapults us into fluid ecosystems. As a consequence we are faced with changing experiences of time and speed, demanding substantial shifts in how we perceive humanity and the planet.

So ‘Space of Flows’ functioned as a starting point, a proposition. The actual theme is the changing world under the influence of digitalisation and the resulting, cursory ways in which we relate to, or acquire knowledge about, our environment. Furthermore, this exhibition critiques the absence of a vision of those in power, who prefer to focus on short-term effects. My reply to this was to learn how to “better observe” certain aspects confronting us nowadays. I am interested in the long curves of the story, listening to the stories migrants themselves have to tell, rather than only focus on the hysterical actuality of the “crisis” of the moment. I wanted to invite photographers who employ digital technology to question the hypes around these issues, people like Rune Peitersen, Esther Hovers, Clément Lambelet and Susan Schuppli. These artists examine such realities, whilst at the same time, striving to make us aware of the underlying mechanisms of the media and the news.

With the exhibition’s subtitle, Framing an Unseen Reality, I wished to explain the position of lens-based artists. Aside from being a reference to photography and video, a frame refers to the statements artists make in and with their work. For example, for this edition of the Kraków Photomonth, I also sought out practices embracing experimentation, and artists who use a variety of visual and narrative strategies, who critically employ specific technologies, or engage in in-depth and original research. Thus, I selected many projects without photography at their core, yet nonetheless still projects in which we can learn about what photographic images are and how they function in our ‘spaces of flows’.

I consider photography as a medium in need of serious scrutiny, while on the other hand I see great potential for the use of the documentary image to shed light on important issues. In that regard, I wish to stay focussed on the documentary, but on those makers who allow artistic licence to fold their materials for the sake of expression, yet without violating the original meaning of their documents.

THB: How do you perceive the festival format? What is its relevance today and what do you foresee for the future? Is there any lesson you drew from curating the Photomonth?

IS: In my opinion there are too many photo festivals. Despite the fact that many of them are billed as having a theme, they often lack a solid curatorial approach. Such a clear focus is lacking perhaps because of the ambition to show too many works and to stage these works in a less challenging design. Besides, the participants are often selected by a group of international scouts. Some of the past exceptions of festivals I have visited include the Rotterdam Photo Biennale (2003), titled Experience and curated by Bas Vroege and Frits Gierstberg, and the Mannheim Biennale for Contemporary Photography (2017), curated by Florian Ebner and others.

I also wonder why so many photo festivals eagerly promote themselves as “a place to celebrate photography?” Although I strongly believe in the festival as a meeting place and as a space for public debate. In Kraków, for example, I organised a panel discussion as part of the well-visited opening weekend in May 2018. I chose to create a walk through the city along the exhibition openings, and arrange artists meetings as well as three panel discussions. A programme like this gives insight into the intentions of the visiting artists and the purpose of a curator’s intervention. It also encourages important and often surprising encounters with audience members. Not least, it projects the motivation for art pieces and their topics back into the real world, thus providing valuable points of entry to the exhibitions. The three panel discussions examined the overarching topics related to the festival’s theme: nature, data and migration. After a journalist had attended the panel Data & Power (in the Bunkier Sztuki Gallery for Contemporary Art), she told me about how impressed she was by the presence of practitioners from the fields of knowledge under discussion. She noticed that the seven artists in the panel felt more inclined to question their research-driven practices, rather than only providing outside information about their projects. This was the case, she said, because the perspectives were brought into the discussion by the experts. She was already imagining attending a follow-up panel, ten years from now, including the same artists and experts, as they all seemed to be in the midst of a thorough research trajectory. Rune Peitersen, one of the artists on the panel, said he found it tempting and rewarding to discuss his work while being able to bounce off the experts: ‘As an artist you use your research to place it in some sort of artistic mold, and finally translate this knowledge into a work of art. By so doing, you gain an artistic expertise which differs from that of the practitioners and theorists in a certain scientific domain.’ In short, I think this defines what I am doing.

I found certain works shown at the Documenta 14 in Kassel last year to be inspiring in the way they sought out connections to local issues, such as Eyal Weizman’s research project Forensic Architecture. Were I to curate another large festival, I would be most appreciative of being given the preparation time to focus more on the spirit of the location and what goes on locally. Although the themes I chose for Kraków have near-universal relevance, many of the topics on display weren’t necessarily rooted within the festival’s immediate sense of place. If I would have had more time I would have done more in Poland. On each journey there, I tried to see as much as I could and meet as many locals as possible, but in the end I was only able to spend ten days in Poland within the period of one year to prepare for the festival on-site.

Occasionally, the freelancing makes me long for a long-term commitment again with a single party, so that foundations can be laid upon where something substantial can be build. Let me work on a project for three years, in which I can sketch broad outlines and have due time for in-depth research. On the other hand, I appreciate the versatility and freedom that characterises freelance curatorship. I often ponder whether I should build on something that does not exist yet, or I better say exists no longer, such as the earlier mentioned excellent Photo Biennale in Rotterdam, that was on for five editions. To my taste it has never had a worthy successor in the Dutch cultural landscape. I see it as a positive development that my teaching and curatorial activities are overlapping more and more, dovetailing and cross-pollinating one another. Nevertheless, my heart is in exhibition-making. Within the context of the extensively-researched and considered exhibitions BABY, ANGRY, and this year the Kraków Photomonth, I ultimately sought to offer an alternative look on the world around us.♦

Image courtesy Iris Sikking.