Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Exposure

Exhibition review by Taous R. Dahmani

A journey to Nottingham Contemporary prompts reflection on Tina M. Campt’s method of “writing to art” in Taous R. Dahmani’s review of Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s Exposure. Dahmani writes to Sepuya’s introspective world, where intricate dialogues between mirrors, photography and identity unfold, challenging traditional spectatorship dynamics. Through a lens of queer and black representation, Sepuya’s work invites viewers to confront societal norms, embrace complexity, and navigate the fluid boundaries of self-presentation.

Taous R. Dahmani | Exhibition review | 14 May 2024

On a morning train to Nottingham, I decided to revisit a passage from Tina M. Campt’s A Black Gaze (2021). When the book came out, I had highlighted this sentence: ‘Seated cross-legged on the floor is my go-to position for writing to art.’ The statement struck a chord with me, prompting a personal vow to try Campt’s method. This visit seemed the perfect chance, but once there, I feared the invigilators might find it unconventional. Would I be allowed to sit on the floor of Nottingham Contemporary, ‘sliding down a wall and claiming the undervalued real estate of a gallery floor,’ as Campt wrote? The reason why I wanted to attempt that strategy in order to “write to” Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s exhibition was because Campt claimed it ‘minimis[ed] you as a viewer and maximis[ed] the work itself,’ adding: ‘Looking up at [the artwork] both breaks up and breaks down some of the traditional dynamics of spectatorship and visual mastery. And when the subject of that art is Black folks, challenging the dynamics of spectatorship and visual mastery is an extremely important intervention.’

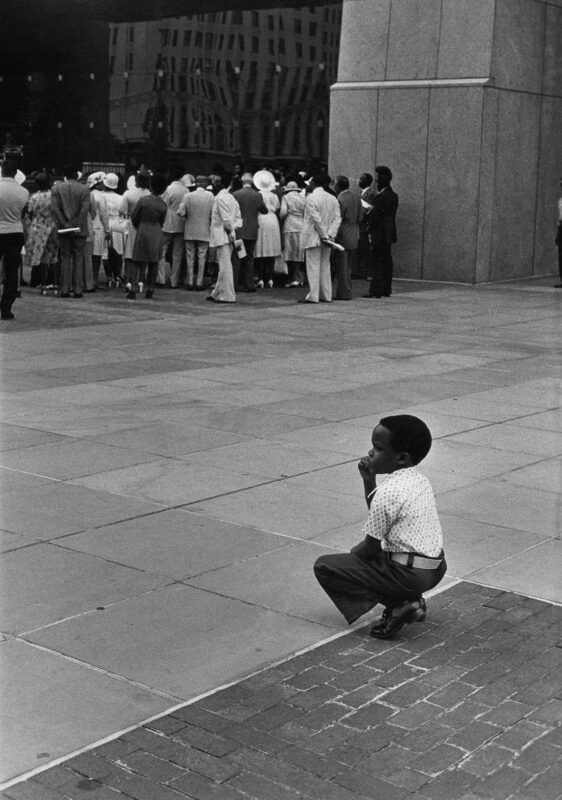

I first encountered Sepuya’s work in 2020 at his solo show in London’s Modern Art, where black figuration and constructed stills through layered acts of looking were key. Four years later, upon entering Exposure at Nottingham Contemporary, I was greeted by a camera on a tripod before a black curtain held by a disembodied brown hand and bulldog clips. Facing this first photograph, I noticed my reflection in the protective glass, positioning my head’s shadow where the operator would be. At that moment, I realised that directly facing Sepuya’s work, rather than ‘looking up’ at it, might be beneficial. This exhibition wasn’t the place for Campt’s method of claiming gallery floors; Sepuya’s large-scale pieces demand that we meet them eye-to-eye.

As I approached Mirror Study (_Q5A2059) (2016), I understood that I was looking at Sepuya’s camera – meaning a mirror must have been placed between the lens and me. This apparatus, and placement of the mirror, suggests the artist is more concerned with what surrounds his camera – objects, people, himself – than with the eventual viewers. The mirror acts as a barrier, its thin reflective metal layer atop glass designed to bounce light back, prompting rumination on the idea of reflection, the image created by light and about photography. In The Mirror and the Palette (2021), Jennifer Higgie elucidated that Johannes Gutenberg opened a mirror-making business in 1438, and within just six years, he pioneered the invention of the printing press. This progression connects the concept of reflection to the notion of infinite reproduction, which ultimately lays the groundwork for photographic theory. Indeed, the coexistence of photography and mirrors has become paradigmatic. In his seminal 1978 essay, which serves as the introduction to the catalogue for his exhibition Mirrors and Windows: American Photography since 1960, John Szarkowski leveraged the metaphor of the mirror to explore the introspective and personal approaches photographers bring to their medium. Similarly, the mirror is an integral part of Sepuya’s artistic process, acting as a catalyst that facilitates layers of analysis of his surroundings. Since 2010, the artist has focused on the artist’s studio as a subject, employing a self-imposed limitation akin to the protocols of a conceptual artist. He describes this approach as a strategy to ‘limit the number of variables as the clearest way to pose a question.’

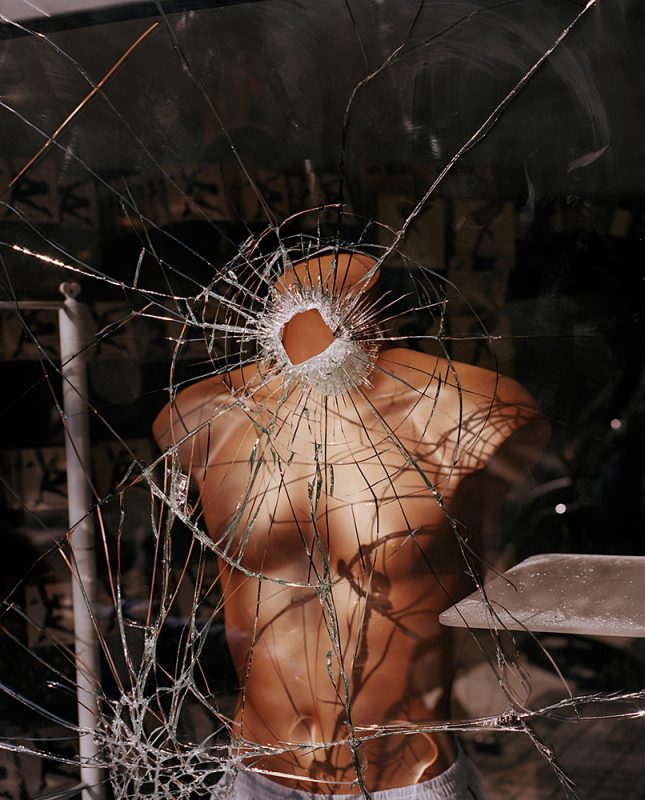

As I progressed to the next set of images, the initially elusive figure of the photographer gradually emerged. Sepuya skilfully navigates the frame, either concealing or unveiling fragments of his undressed body, and thus, his identity. He delicately reveals details of his anatomy, including the hairs on his neck and arms, and close-ups of his back and torso. Photograph after photograph, his progressive apparition transforms the studio into a stage. We are witnessing the documentation of a performance, a play with characters and, of course, a message. The photographs or the mirror – in Sepuya’s world they are in constant dialogue – predominantly depict self-portraits or portraits of close friends and lovers. Beyond mere self-recognition through self-representation, there is a definitive act of self-presentation; a celebration of the artist’s freedom and agency. The performed gestures subvert gender binaries and reclaim their fluidities, so much so that Sepuya quite literally blurs surfaces and thus boundaries. We observe the movement of bodies on a stage, enacting intimacy and at the same time rendering a political identity that is both queer and black. Sepuya’s photographs recall the words of Judith Butler, who noted in Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex (1993) that the performative aspect of gender enables subversive actions capable of challenging and destabilising conventional norms. By inviting his friends to act for the mirror-camera in his studio-stage, Sepuya creates an experimental sanctuary for the development of a queer visual language. Engaging with Sepuya’s photographs is not straightforward; they challenge us to interpret and decode, but, at the same time, the repeated frameworks facilitate a steady understanding of his visual strategy. If, indeed, the mirror is not just a reflection but a boundary, then viewers are mere welcomed spectators. The exhibition feels like an invitation to partake in the acknowledgment of too often marginalised queer black and brown individuals. Viewers are brought into their proximity, invited to stand alongside them, yet rightfully kept at bay.

Sepuya’s work draws from a rich history of queer imagery, from the kouros figures of Ancient Greece to Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s Snap Shot (1987) and Caravaggio’s ephebes. These motifs have come to symbolise queer identity, thus raising the question: how can we interpret the revival of these motifs in today’s photographic production? As Sepuya bestowed, as an invitation to think complexly, ‘representation is not an agenda,’ and indeed his visual language strives for something more, something that revived, for me, José Esteban Muñoz’s Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (1999), Here, Muñoz discusses a process in which individuals tactically interact with societal norms to forge a self that critically diverges from mainstream culture. He emphasises behaviours and gestures as crucial to the identity formation of queers of colour, beginning his book with the statement: ‘There is a certain lure to the spectacle of one queer standing onstage alone, with or without props, bent on the project of opening up a world of queer language, lyricism, perceptions, dreams, visions, aesthetics and politics.” It leads one to question whether Muñoz is actually describing Sepuya’s own photographs some 20-odd-years before their creations.

The studio and its “inhabitants” are constants in Sepuya’s work, existing in a fluid space where time seems relative and ideas and iterations evolve and transform. In the second gallery, elements such as mobile mirror flats from the studio transition into exhibition structures showcasing his latest photographs. Unlike the first room where close examination was encouraged, here Sepuya invites viewers to navigate the photographs, guided by their spatial arrangement. He transforms the space by bridging the private theatricality of the studio with the shared communality of the gallery. Leaving the exhibition, and tucking away my copy with Campt’s book, I was reassured that sitting wasn’t necessary, as Sepuya himself ‘maximises’ his work. He shifts spectator dynamics, elevating and redefining engagement by challenging traditional approaches. On the train back to London, I was left with the feeling that visitors ought to stand in the gallery, embracing homoerotic pleasure, whilst also striving to become accustomed to nuanced discomfort and grappling with complex ideas about image-making. ♦

All images courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann Zurich/Paris © Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Paul Mpagi Sepuya: Exposure ran at Nottingham Contemporary until 5 May 2024.

—

Taous R. Dahmani is a London-based French, British and Algerian art historian, writer and curator. Her expertise centres around the intricate relationship between photography and politics, a theme that permeates her various projects. Since 2019, she has been the editorial director of The Eyes, an annual publication that explores the links between photography and societal issues. She is an Associate Lecturer at London College of Communication, University of the Arts London. Dahmani’s curatorial work was showcased at Les Rencontres d’Arles, France, where she curated the Louis Roederer Discovery Award (2022). Dahmani is set to curate two exhibitions at Jaou Tunis, Tunisia (2024).

Images:

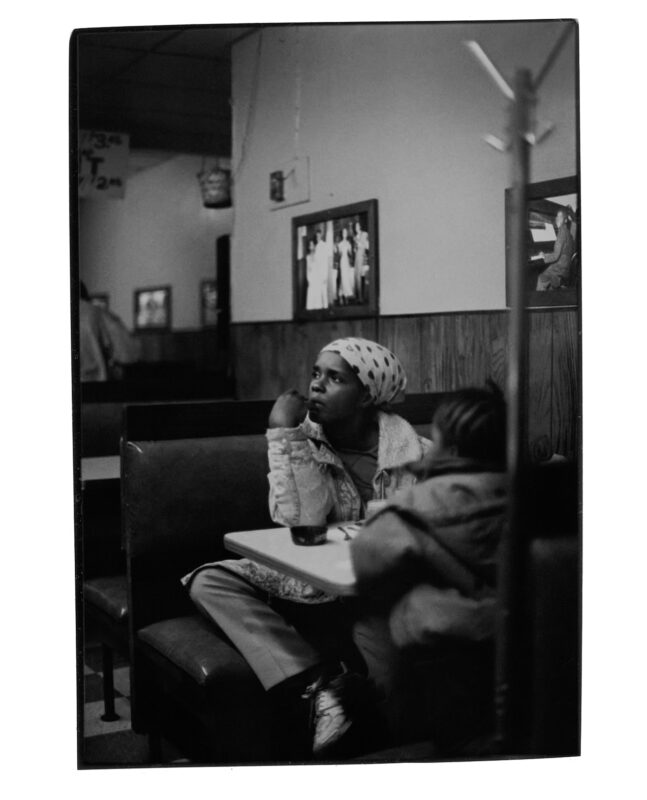

1-Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Twilight Studio (0X5A4176), 2022.

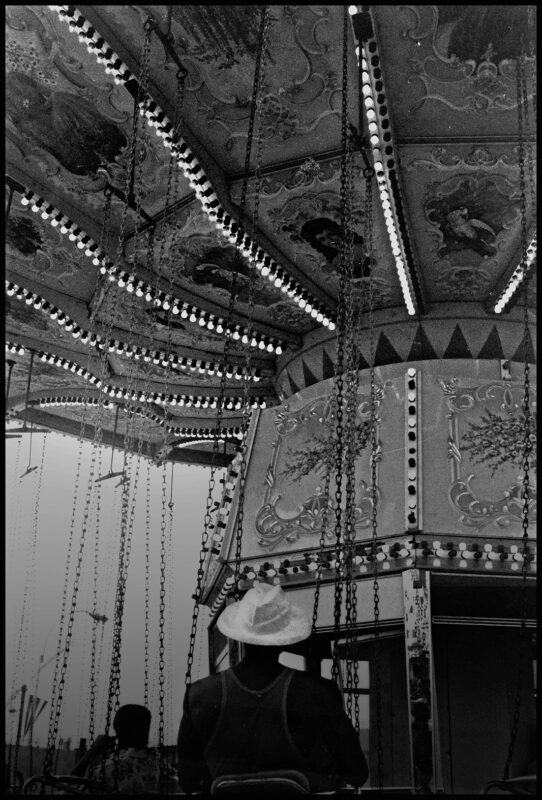

2-Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Model Study (0X5A7126), 2021.

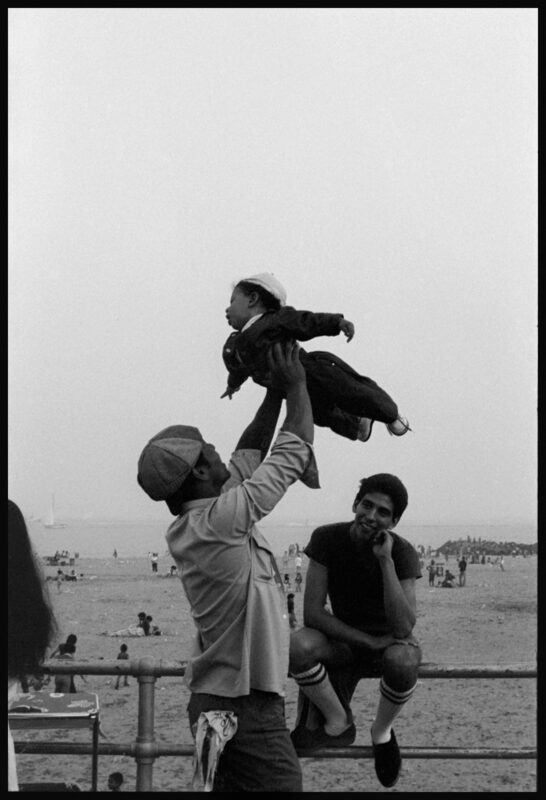

3-Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Daylight Studio Camera Lesson (0X5A2613), 2022.

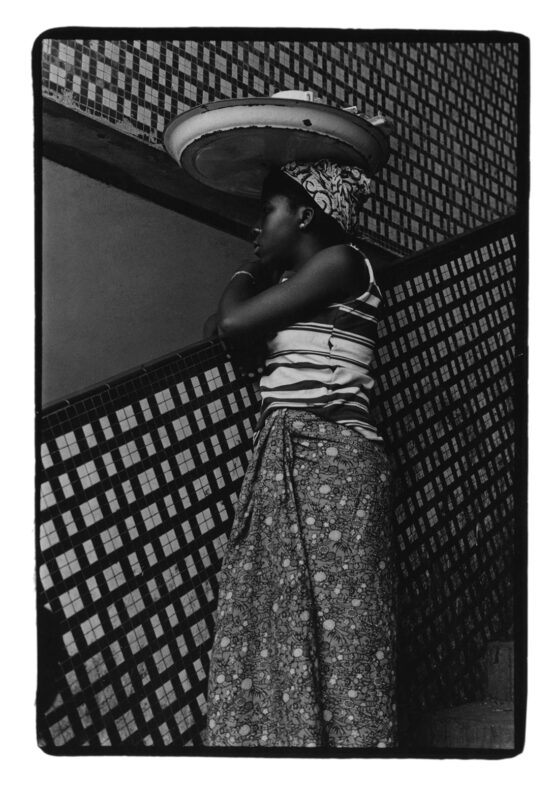

4-Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Pedestal (0X5A8997), 2022.

5-Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Studio Mirror (_DSF6207), 2023.