Joanna Piotrowska

All Our False Devices

Exhibition review by Eugénie Shinkle

I spent most of the 1980s scared out of my wits. Environmental pollution, stranger danger, the chance that we might be wrong about the sun, and that it might burn through its supply of hydrogen and flicker out not in five billion years, but tomorrow or the next day… it was a scary decade, but the spectre that I lost the most sleep over was nuclear war.

In May of 1980, the British government released a booklet entitled Protect and Survive as part of a civil defence series on living through a nuclear attack and its aftermath. The first image in the pamphlet was terrifying – a three-colour graphic of a mushroom cloud boiling skyward, the result of an explosion so cataclysmic that it wasn’t clear you would actually want to survive it. Standing firm in the face of this prospect, Protect and Survive instructed citizens to build a fallout room in their home, complete with a thick-walled ‘inner refuge’ cobbled together out of whatever household items they had to hand – doors, furniture, clothing, books, bags of earth or sand.

Luckily for humanity, the need to build a fallout room or an inner refuge never arose, but such ad hoc shelters stood little chance of weathering a nuclear explosion, and even if they had, the body was still likely to succumb anyway – there’s not much that sofa cushions and stacks of books can do to prevent a slow death by radiation poisoning. But Protect and Survive wasn’t actually about protection or survival. It was an antidote to pervasive feelings of helplessness and fear – a way of keeping hope alive in the face of what were probably insurmountable odds. Building a fallout room and an inner refuge was a demonstration of agency – a way of giving people the sense that they could do something.

Joanna Piotrowska’s All Our False Devices, currently on display as part of Art Now at Tate Britain, explores the subtle balance between agency and vulnerability. Her work is often said to deal with gesture, but the installation at the Tate Britain – a selection of framed black-and-white photographs and three 16mm film loops – asks us to think about the term beyond its obvious associations with body language and nonverbal communication. A gesture can also be understood as a testimony, and the various gestures that comprise All Our False Devices testify, in different ways, to the nuanced character of human frailty.

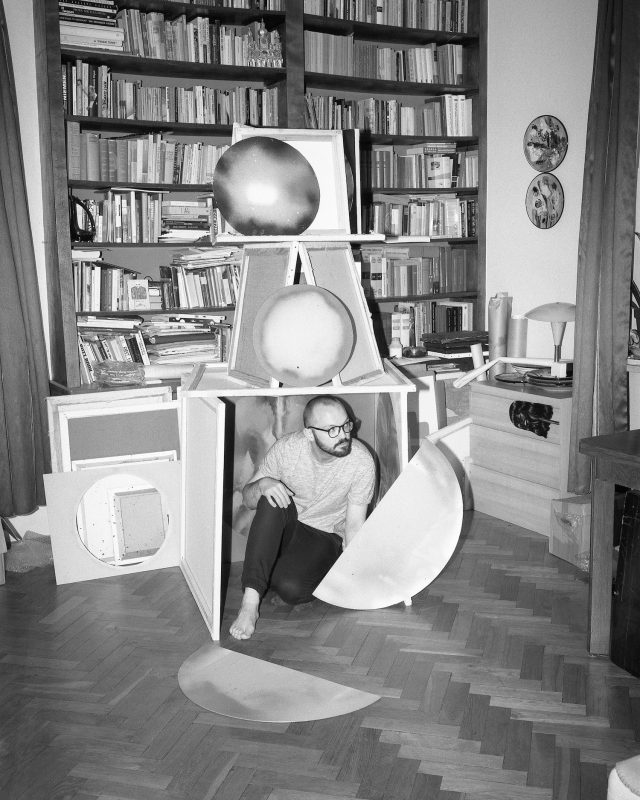

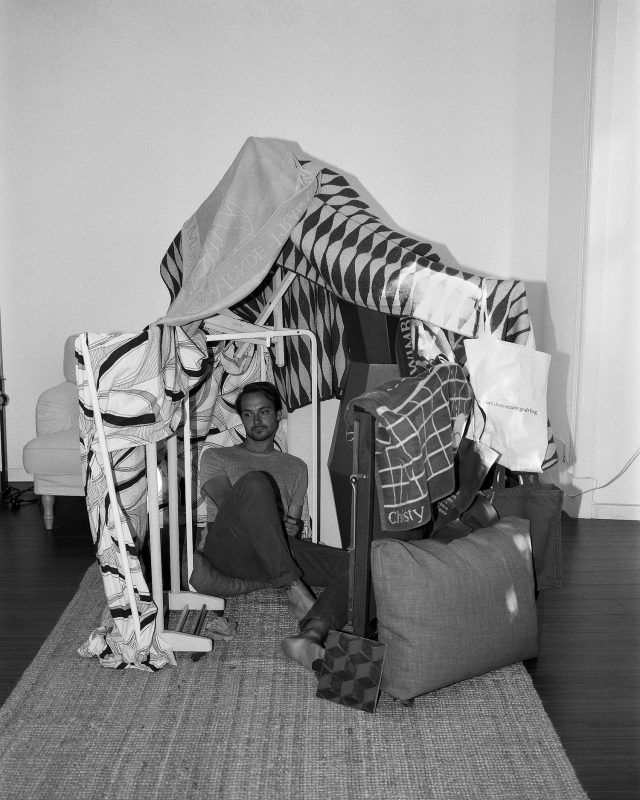

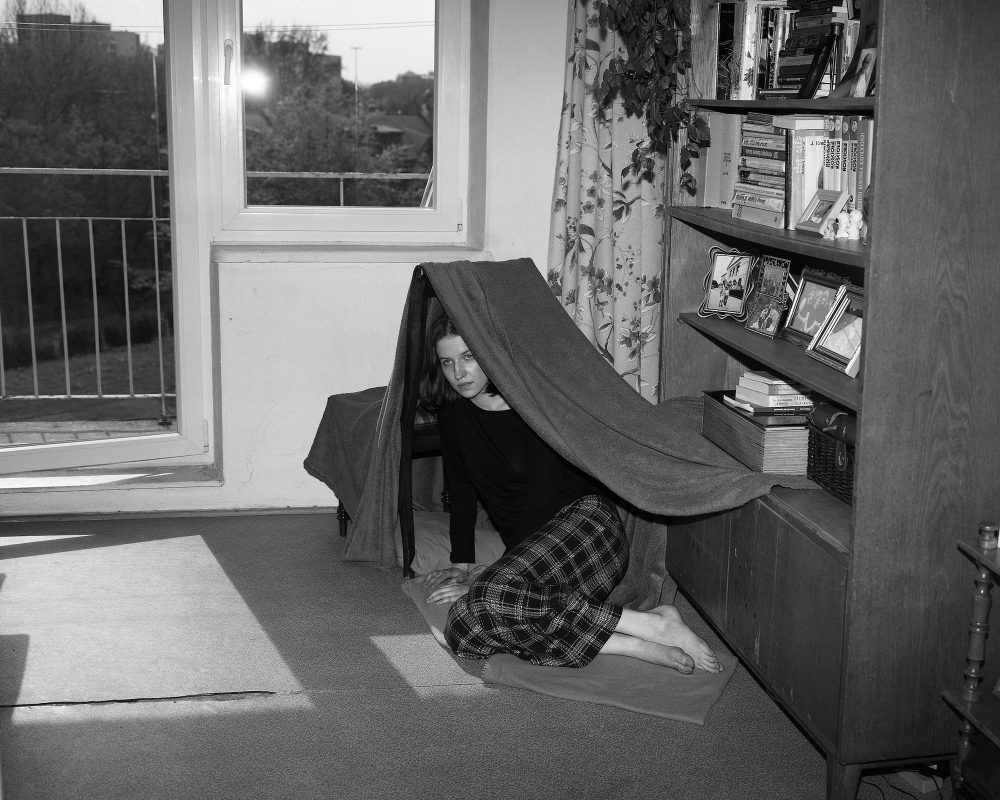

Between 2016 and 2018, Piotrowska invited subjects living in four cities (London, Warsaw, Rio de Janiero and Lisbon) to build shelters in their homes. Like the inner refuge, these shelters are weird eviscerations, thrown together out of things displaced and dragged out of cupboards: blankets and chairs, books and sofa cushions, along with unlikely items like rocks and lumps of rubble, musical instruments, empty picture frames and random pieces of metal. Some are imaginative and even inviting: a cosy fort made of a patio umbrella and patterned throws, a wigwam topped with a wreath. Others feel like outward manifestations of inner pain: in one image a woman lies curled in foetal position in a hallway, sheltered by an unsettlingly clinical assemblage of metal racks and white sheets. In another, Piotrowska’s subject lies prone on a mattress, buried under layers of bedding with only her head showing. All of these arrangements are unstable and temporary, but their fragility is beside the point, because their purpose is symbolic. They are expressions of identity – of a childlike impulse to create, and a more grown-up will to survive. Less carefully planned than the domestic interiors of which they’re a part, these enclaves represent something primal – a basic animal instinct to shield the self from unnamed threats.

Some of the most pervasive of these threats are invisible – psychological violations directed not at the body, but at our sense of self. The complex, gendered nature of such threats is the subtext of two of Piotrowska’s films, which feature young women working through a series of odd gestures and poses, adapted from instructions in self-defense manuals. The films are projected small and low on the wall, the images nearly hidden by the machinery of the projector. You have to come close to see what’s going on, leaning in to observe what look like slow rituals that the women have yet to properly master. Alternately stable and wobbly, Piotrowska’s subjects rehearse the same movements over and over, their performances wavering between futility and triumph.

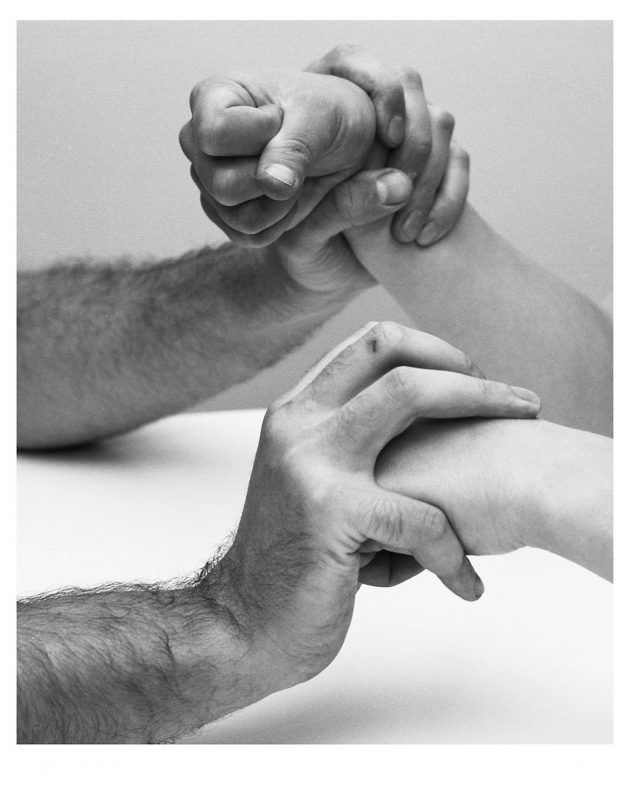

Another film features a pair of hands, shot from the wrist down, one exploring the other, feeling its way along the uneven contours of the wrist and forearm. Intimate and strangely hypnotic, it’s a body’s tactile reflection on its own being, and a meditation on the enigmatic nature of touch. The reversibility of touch was something that preoccupied philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty throughout his career: ‘When my right hand comes into contact with the left hand palpating something,’ he wrote, ‘its activity easily reverses into the passivity of an organ being touched by the other hand. At the crossroads of touching and being touched, my sensible body manifests itself both as a tactile agent and a patient … ‘. For Merleau-Ponty, our relation to the world begins with the body, and as such, it is always, simultaneously, resolute and yielding.

Vulnerability, in other words, is an essential part of being human rather than a failing; being itself – human or otherwise – involves a fluid state of compromise between strength and surrender. Vulnerability is something intimate and political, overwhelming but also somehow comforting. Protect and Survive encouraged the building of shelters as a way of renouncing this. Installed in a high-ceilinged, imposing room that’s been wall-to-walled with thick blue carpet like a soft cyan sky dropped groundward, All Our False Devices encourages us to occupy this ambiguous state for a moment and to embrace it as something fundamental. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist, Southard Reid, London, Madragoa, Lisbon, and David Radziszewski, Warsaw. © Joanna Piotrowska

Installation views of Art Now: Joanna Piotrowska: All Our False Devices at Tate Britain, March 8th – June 9th, 2019. Photo: Tate Photography (Matt Greenwood)

—

Eugénie Shinkle is a photographer, writer, and Reader in Photography at the University of Westminster. She writes for various publications such as Foam, Aperture, Fashion Theory, American Suburb X, and The Journal of Architecture. Recent work includes Fashion Photography: the Story in 180 Pictures (Aperture/Thames & Hudson 2017) and ‘Painting, Photography, Photographs: George Shaw’s Landscapes’, in George Shaw: A Corner of a Foreign Field (Yale University Press 2018).