Writer Conversations #5

David Campany

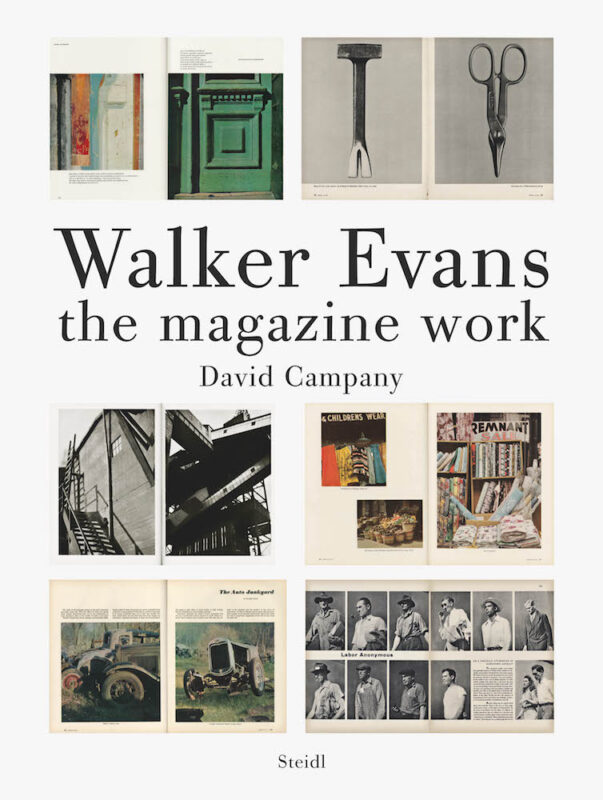

David Campany is a curator, writer and educator. His books include Indeterminacy: thoughts on Time, the Image and Race(ism), co-authored with Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa (MACK, 2022); On Photographs (Thames & Hudson, 2020); Walker Evans: The Magazine Work (Steidl, 2013); Photography and Cinema (Reaktion Books, 2008) and Art and Photography (Phaidon, 2003). His curatorial projects include #ICPConcerned: Global Images for Global Crisis (2020), The Lives and Loves of Images (2020) and A Handful of Dust (2015).

At what point did you start to write about photographs?

‘About’ is a complicated word. I first started to write during my undergraduate years. I was on a wildly ambitious 50/50 programme, half image-making, half writing, informed by a number of disciplines: semiotics, psychoanalysis, Marxism, feminism, post-colonial theory, theories of institutions and ideology, aesthetics, phenomenology and film theory. Reading preceded any writing. Lots of it. I was struck early on by the difference between writings that began from the particular – this or that image – and writings that began with a theoretical abstraction, and deployed photographs as illustrations or examples. Both have their merit, of course, and I wrote in both ways at that time. Seven or eight years later, opportunities came my way to write for magazines and books, and I had to figure out if I could do something. By then, I had already been teaching for a few years. I suspect the daily practice of getting complex ideas into sentences comprehensible to students shaped how I began to write. As the years passed, I became somewhat averse to writing ‘about’ photographs, preferring to write around them, off them, in parallel, leaving the image as something for the reader to consider for themself. This came from the realisation of how little words can do in the face of the image, and to pretend otherwise was folly. That ‘little’ is vitally important, but it is little.

What is your writing process?

Everyone has their own creative rhythms and must accept them, because they cannot really be altered. I’m not all that productive but I don’t waste time. I usually work on two texts at once because I get stuck so often, and instead of doing nothing I can switch.

Most often, I write in order to find out what I think about things, and I try to write in a way that will carry me and the reader through that thinking. That means that the form of the writing is always in play, and cannot be taken for granted. I never know if a piece of writing is going to work out.

Occasionally, I’ve written polemics, and polemical writing was certainly the strongest kind I encountered as a student. I still relish reading strident texts, past and present. They do help to clarify. But I discovered I was temperamentally unsuited to that mode, which is premeditated and programmatic. Writing to discover what you think is quite different. It is speculative, risky, uncharted. Against that, I enjoy the parameter of the word count. If there’s no limit, my writing gets baggy. Not always, but often. (Maybe that’s why I’ve never blogged.) Interesting writing can be any length. A hundred words, a thousand, ten thousand.

What opened me up was the realisation that I could include images alongside my words. The richest experiences I’d had as a reader were with writings that included images, mainly in books on cinema. I liked it when the choice and sequence of images threaded through a text seemed almost like a form of writing. My own writing is done this way wherever possible. If I can get the ‘image track’ to feel interesting, to me at least, I can then begin to write. I don’t know of many other writers who do this. My interest in this approach is why I also became a curator and an editor of photographic books. There are parallels. I have often encouraged students to write this way, beginning with the choice of images. I’ve noticed it can work wonders for smart students who thought they had no chance of writing well, or in a way that they might enjoy and benefit from. If you fear the blank page, put an image on it. (Having the image on the page for the reader to look at for themselves is also a great discipline for a writer.)

I rewrite a lot. Partly, this is because my first drafts are lousy, but I’m trying to get my words to work well on the ear. I’m sure that comes from teaching, but also from the fact that I’ve always been impressed by good public speaking. If my words are dead to the ear, I know I need to rewrite. That’s not a rule for all writing. It just works for me.

The invitation plays a key part. I am fortunate in that institutions, publishers and image-makers often ask me to write. That element of surprise is really useful, as is the feeling of confidence one gets when someone likes your work and thinks you could do something worthwhile. I’m as likely to write for a little-known artist as for a major institution. Follow the work, not the reputation.

Sometimes I would rather not produce a text on my own, feeling I have more interesting things to discuss than to write. In these situations, I’m likely to suggest a conversation or written exchange, rather than an essay. Some of my published conversations – with Jeff Wall, Anastasia Samoylova, Stephen Shore, Sophie Rickett, Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa and Daniel Blaufuks, for example – are among my favourite writings. I should say here that these conversations really are conversations. They are open-ended, speculative, responsive and all about the exchange of ideas. I know this project has the word ‘Conversations’ in its title, but it doesn’t really contain conversations. What I’m writing here is a response to a questionnaire: an efficient way to solicit formatted ‘content’. That’s why the questionnaire is such a dominant form these days. A conversation is the opposite.

What are the questions or problems that motivate your writing?

Mixed feelings are the best motivation for me as a writer, and as a viewer. If my feelings are too clear to begin with, then there’s little in it for me. As for problems, I think the largest one has been the growing gap between writing that takes place in the academy (universities) and writing that takes place outside. I think this is worrying for a society. When I became a writer, having worked in a university for a while, that gap was already becoming very real, and I could see it had political consequences. The smart stuff wasn’t getting into the world, and when it did, it was not often understood. As neo-liberal capitalism marched its violent way onwards, the academy retreated from the public square, making its critiques and presenting its alternatives to its peer group, in ways its peer group appreciated. I’m exaggerating, but only slightly. As an emerging writer, I had to face that in a very immediate way. I made the decision, for good or bad, to publish outside of the academy. I’ve written very few “peer-reviewed” essays for academic journals, for example. (Seriously, who wants to live in a peer-reviewed culture? Sounds vaguely Stalinist to me. Sure, I want my brain surgeon to have read the right journals. Culture is different.) The essays I have written for academic journals were to see if I could do it on those terms, as an exercise. Once I’d ticked that box, I wanted other challenges, other audiences, which I didn’t know existed but I had a feeling they might. (I’m always fascinated to see how people who write about photography describe themselves. ‘Theorist’. ‘Art historian’. ‘Critic’. ‘Academic’. The aversion to the term ‘Writer’ says a lot.)

There is such anxiety around images. Rightly so, and for a lot of reasons. But there is a tendency for writing, for writers on the visual arts, to step in and overwrite, to attempt to supply the ‘script for looking’, to take away the anxiety the image produces and stabilise things. More often than not, this is prejudice and preference masquerading as reason. One sees this in everything from museum wall texts, to reviews, blogs and critiques. Images get ‘explained’ in terms of authorial intention, biography, strategy, what we ‘ought’ to be thinking, and so forth. This runs the risk of diminishing us all as viewers, patronising us while pretending to enlighten. Moreover, it refuses the essential ambiguity of images. There are forms of writing that don’t do this, that keep the door open, however awkward and painful that can be. Ambiguity, the openness of the image, can be an anxious problem… But it is the only way out, so we ought to embrace it.

The other problems that motivate my writing are self-imposed. They involve finding new relations between image, thought and language.

What kind of reader are you?

Pretty voracious and wide-ranging. I am also a re-reader. Texts can be returned to, in order to figure out how they were written, and as a way of measuring one’s own intellectual and emotional development. There are novels and philosophical essays I make an effort to reread every few years. They stay the same. I change.

How significant are theories and histories of photography now that curation is so prominent?

I had no idea curation was so prominent. Nevertheless, writing is writing and curation is curation. They share some concerns and approaches, of course, but, as a writer and a curator, I’m interested in the differences.

What qualities do you admire in other writers?

Unimprovable sentences. The ability to get paid. (As far as I know, we’re all doing this project for nothing.)

What texts have influenced you the most?

Influence is largely unconscious, so don’t ask me. I am not being flippant. The answers we give about our influences are merely the answers we are able to give. Among my conscious answers, the ones that come readily to mind are the writings of Roland Barthes (on almost anything other than photography), Susan Sontag (same), Jacques Derrida, Fred Moten, Susan Stewart, Fredric Jameson, Raul Ruiz, Clarice Lispector, Marguerite Duras, Julia Kristeva, Gilles Deleuze, Victor Burgin, Frantz Fanon, Adam Phillips, George Orwell, Lydia Davis, Samuel Beckett and Virginia Woolf. I would give a different answer tomorrow, I’m sure. Between what we know and what we don’t, there are hunches and intuitions. I have a hunch that the texts influencing me most profoundly were, and are, song lyrics. Words as sung. I cannot memorise a line of poetry, even if it means the world to me. I remember songs without even trying. I cannot imagine this has not had an effect, but I am not sure I could define it.

What is the place of criticality in photography writing now?

There are many places. It’s good to be mindful of this.

The space of critical refusal interests me. For example, how would discussions about identity take shape if one considered the possibility that the most interesting and profound things about identity do not offer themselves to the camera, to visibility? Or, what do we do about the fact that the narrowly consensual categories of both the mass media and art world demand certain conformities? At what points and in what situations might a commitment to photography be a walking away from it, and a turning towards something else, either as a maker, writer or viewer? There are photographers who face these questions and find other ways. And there are writers who have advocated for this too. The endless ‘commitment’ to photography, the presumption that all things of value can and must be available to its often-crushing and limiting embrace, is a very real issue. This should be faced as a matter of some urgency. (I don’t feel committed to photography at all costs, merely fascinated by it, and life beyond it is rich.) Critical refusal ought to be a vital part of the way photography is thought, discussed, taught and written. It should always be on the table. There are many positive signs that this is happening.♦

Further interviews in the Writer Conversations series can be read here.

Click here to order your copy of the book

—

Writer Conversations is edited by Lucy Soutter (University of Westminster) and Duncan Wooldridge (Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London), upon the invitation of Tim Clark (1000 Words and The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University).

Images:

1-David Campany

2-Book cover of David Campany, On Photographs (Thames & Hudson, 2020)

3–Book cover of David Campany, The Lives and Loves of Images (Kehrer Verlag, 2020)

4-Book cover of David Campany, Walker Evans: The Magazine Work (Steidl, 2013)

5-Book cover of David Campany, #ICPConcerned: Global Images for Global Crisis (G Editions, 2021)