Katrina Sluis

Digital Curator at The Photographers’ Gallery and Senior Lecturer

London South Bank University

The latest instalment in our Interviews series sees Lewis Bush speak with Digital Curator at The Photographers’ Gallery and Senior Lecturer in Photography at London South Bank University, Katrina Sluis. Sluis takes us into photography’s parallel – or not so parallel – world of networked culture, and discusses the challenges of exhibiting the vernacular digital-born image, how we might address questions of authorship, labour and cultural value in an age of photographic ubiquity, and how one might practically curate, disseminate and archive a photographic culture defined by viral reproduction and excess. Sluis also reflects on the manner in which the common binary between ‘immaterial’ and ‘physical’ mediums, which assumes the digital image has no materiality – is both problematic and political in her view, and the different set of tools or logic that are now required to consider the limits of semiotics or psychoanalysis in an age when machines (and not humans) are the dominant readers of images.

Lewis Bush: Hi Katrina, thanks for agreeing to this discussion. Having it at this moment seems fitting given what feels like a growing public awareness about the specifics of digital imaging and display, and also about the politics of data, networks, and technology more broadly, not least in the wake of events like the US election where these things have played important parts. To start off, perhaps you could you tell me a bit about how and why you first became interested in working specifically with digital images? I think I’m right in thinking your background as a photographer was originally working rather more traditionally with large format cameras and analogue film?

Katrina Sluis: That’s right – I originally trained as an artist in the 1990s in Sydney at the College of Fine Arts. I actually majored in painting, but defected to the Photomedia department in my final year, inspired by the amazing group of women teaching there – Debra Phillips, Rosemary Laing, Lynne Roberts-Goodwin, Maureen Burns, Paula Dawson and Simone Douglas. I was also drawn to photography for its richness as a conceptual tool – and the way Australian photographers were engaging with post-colonial, feminist and post-photographic discourses. There is also a strong history of experimental Media Art there, and staff in many departments – from painting to sculpture – were experimenting with new technologies. Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art even did a show of CD-ROM art in 1996! So I didn’t think anything of working with a large format camera in the morning, seeing a performance by Stelarc at lunch, then photoshopping in the computer labs in the evening.

On the weekends I would dial-up to my local BBS in order to play a MUD or teach myself HTML, and I later supported my practice working as tech support at CompuServe Pacific, an early internet service provider. However it actually took a long time for me to connect those specific spheres of my life – what I was doing in my art and what I was doing on the net – until the early 2000s.

LB: I am going to slightly show my age here by saying that for those of us who were growing up in the early stages of the internet, digital imaging and so on I think there is a tendency to retrospectively assume these things rather separated off from other areas of art practice so it’s fascinating to hear how fluidly you were moving between these things. Leaping forward to the present, amongst other roles you are now curator of the digital programme at The Photographers’ Gallery, a post which I believe was specifically created when the gallery reopened at its new location in 2012. Was its creation about audience engagement, or a response to a specific recognition at the gallery that digital photography was being somewhat neglected in favour of works which favoured more traditional modes of gallery display? Or was it perhaps something else entirely?

KS: I think there was an understanding at the gallery that photography’s collision with network culture created a number of technical and conceptual challenges they didn’t have the capacity to deal with. For example, how do you exhibit the vernacular digital-born image? How do you address questions of authorship, labour and cultural value in an age of photographic ubiquity? How do you practically curate, disseminate and archive a photographic culture defined by viral reproduction and excess? And what changes to institutional structures are required? As you indicate, the issue of audience(s) underpins many of these problems. If public cultural institutions have some claim to be ‘representational’ then there’s a need to engage with the photographic practices of our audiences which reflect in complex ways the changing meaning and agency of the medium.

LB: Yes, that makes absolute sense. Speaking as a teacher who often brings students to the gallery, I’ve found of these engagements with more vernacular digital imagery can sometimes act as a great gateway to complicated ideas and discussions. I also find it personally very refreshing because of the way an exhibition of say, ‘lolcats’, has something of a levelling effect when seen in conjunction with the often more conventional displays upstairs in the galleries. In a field where photographers are often keen to define themselves in opposition or difference to other photographers I find it a nice reminder that all photographic images have much more in common than in difference. Moving on from this thought though, do you find there are any particular challenges that come with working with an immaterial rather than physical medium, or for that matter particular opportunities that excite you about these types of media which you don’t find with physical photographs?

KS: First of all, I think this binary between ‘immaterial’ and ‘physical’ mediums, which assumes the digital image has no materiality – is both problematic and political. In this respect, the key challenge of working as a digital curator is finding ways to make visible and intelligible the various techno-social infrastructures which sustain the photographic image today. This requires a shift in thinking about not only what an image represents, but how it is operationalised by both human and non-human actors. This is very hard for photographic institutions who have championed photography as an art form, as they had to downplay its role as a reproductive technology in order to emphasise the creative legitimacy of the photographer who pressed the shutter.

On the other hand, one fantastic aspect of working in a photography institution is that the practice of the artist is not the sole privileged site through which culture might be understood. One can take seriously the knowledge of amateur photography communities, computer scientists or even venture capitalists who increasingly influence the direction and shape of photographic culture and its curation.

But to return to your original point, when I joined the gallery there was definitely a sense that digital programming is somehow less expensive, less labour intensive and easier because you sidestep a set of problems concerning the specificities of archival prints, insurance, transport and so on. To some extent, this is true. However, having seen the number of all-nighters I’ve pulled trying to troubleshoot problems with video codecs, network issues, and the cost and logistics of running hundreds of metres of CAT 6 cables through five floors of the building I’m sure my colleagues would now beg to differ.

LB: Picking up your point about the way institutions have championed photography as an art form, and the gradual acceptance of this idea, do you think there are any parallels with the way people treat artworks which are primarily digital in nature? I have seen quite a few exhibitions in recent years where it seemed the curators didn’t really ‘get’ digital art works and were trying very hard to force them into the shape of more traditional analogue works. An example being an interactive digital artwork being displayed as a screen captured video, or even worse as a screenshot or print. To put the same question in another way, are people still basically very hung up on the idea of photographs as objects?

KS: These curatorial practices you describe are, essentially, a result of seeing photography primarily as ‘visual content’, a process which renders the computer interface as transparent or invisible. Worryingly, I think there is also sometimes a mistrust of the audience and a perception that they need the work to be presented to them in a familiar format in order to engage with it. A related problem is that there’s also (unsurprisingly) very little technical expertise in cultural institutions, especially from a curatorial perspective – it’s hard to find hybrid people who understand photography as both a technical and cultural language.

To take up your point about the fetishisation of photographs as objects, the nostalgia for the analogue in digital culture is something we directly addressed when we devoted our recent Geekender to the “Hyperanalogue”. I think the persistence of the object is both a product of a crisis of authorship felt keenly by a sector of the community, but also part of a wider desire to seek out allegedly ‘authentic’ forms of expression in an increasingly accelerated consumer culture.

LB: Yes, quite true about the transparency of the technologies that render the digital image. Although, to play devil’s advocate, one could perhaps say that is a consistent tendency in all forms of photography. How often do you hear analogue photographers consider the environmental consequences of the silver mining required to make their prints, for example. Your point about the authenticity of analogue culture is also interesting in that at least amongst my generation there also seems to be an interest in early internet culture and technology for similar reasons. Animated GIFs are one obvious example, a largely obsolete format which has experienced a strange revival. I wonder if you have any thoughts on that?

KS: I agree that analogue photography doesn’t somehow sidestep the politics of production. However, when the photographic image becomes the output of software, it requires a different set of tools or logic to unpack – consider the limits of semiotics or psychoanalysis in an age when machines (and not humans) are the dominant readers of images. In this respect, the networked photograph resembles a “two faced Janus”, which on the one hand points to the world of representation, and on the other to algorithmic reproduction and the cybernetic dynamics of pattern and randomness. And yet the answer in parts of the visual literacy and photography community to this problem is to “slow down” the image, and embrace “slow looking” in order to get an even more detailed reading of the the singular, enframed, image. In the gallery we have been running workshops with our PhD researcher, Nicolas Malevé, who is re-staging a California Institute of Technology experiment where participants are asked to describe images which have been shown to them for a number of milliseconds. This experiment became the model of visual perception underpinning the development of ImageNet, a database used to train machine vision algorithms. Resituating this experiment in The Photographers’ Gallery has been immensely productive in unpacking the cultural value of spectatorship and visual pedagogies for both humans and machines.

With respect to the resurgence of the Animated GIF around 2010-2012, I’m not sure this is the result of a younger generation suddenly longing for a more authentic web, or wanting to engage with the politics and aesthetics of early net culture. There are indeed projects like Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenscheid’s One Terabyte of Kilobyte Age – which uses Tumblr to circulate homepages from the Geocities archive – that have engaged a new audiences unfamiliar with the early amateur web. We were fortunate to show 10,000 of these web pages at the gallery over 3 months in 2013. At that time Olia gave a talk at the gallery about the specificity of early GIF culture, and how it was the format’s ability to support transparency as opposed to looping, which was crucial. She noted that transparency gives the image the ability to exist anywhere on the web – on any page or any background. In modern GIF culture the use of transparency has all but disappeared, and the dominant form of GIF is televisual or cinematic – consider the endless “reaction” GIFs plucked from popular TV or the fetishisation of the ‘cinemagraph’ by the Tumblr community. Its resurgence is also related to the the increasing pressure for cultural expressions to survive in an economy of attention, and the death of plug-ins such as Flash in a mobile web age.

LB: A key part of the digital programme is the Media Wall, which is also one of the first things visitors see when they enter The Photographers’ Gallery. How do you approach commissioning works for such a prominent display? Does this process occur in close collaboration with other curators at the gallery or do you have high level of autonomy to decide what appears here?

KS: Whilst the Media Wall is very prominent, the digital programme actually has a lot of autonomy – it has less status in the institution, for the practical and historic reasons we have already touched upon, and different aims to the rest of the programme. Within the limits of our resource we have always tried to work in a very lightweight and opportunistic way, trying out different approaches and working with partners (such as Animate Projects or Brighton Photo Biennial) to co-commission work where possible or taking the lead from online communities.

LB: Are there any particular commissions for the Media Wall or artists you have worked with as part of the digital programme that stand out for you?

KS: When the gallery’s exhibition programme has had a very clear theme or concern in a single season, it’s been productive to reflect on the digital context for those ideas with an artist’s commission. For example, alongside Human Rights Human Wrongs, we were able to commission James Bridle to work with Picture Plane, a company which specialises in CG architectural visualisations, to produce a work which made visible a series of ‘unphotographable’ sites of UK immigration detention. But alongside these artists’ commissions it has also been crucial to develop a strand of Media Wall programming which specifically deals with the networked image culture. These projects are incredibly labour intensive and raise all sorts of tricky curatorial problems, but have offered us the opportunity to work with cat photographers, the visual culture of motherhood, food photography and (in our next season) computer games and screenshot culture.

LB: You have also overseen the launch of unthinking photography, a fascinating online resource on the intersections of photography and algorithmic automation, networks and more. This site seems to mesh with your work at the Centre for the Study of the Networked Image at London South Bank University, which you also co-founded and co-direct. These topics feel like something of a wild frontier, with much happening but with little regulation or public awareness of them. What is the aim for you of engaging with them in this way?

KS: Unthinking Photography was born out of a desire to start mapping a very different ‘image’ of digital photography, which doesn’t originate with the age old issue of image manipulation but what might be called photography’s ‘softwareisation’. I was also aware of the need to generate a resource on these issues, given the number of frustrated photography students I kept meeting! And in contrast to the scathing rejection of Internet culture in some parts of the photographic community, I was also keen to take seriously the world wide web as a site through which photographic knowledge is produced. For example, what we can might learn about photography from YouTube and its users? What can we learn about machine vision through a TED Talk? How do we understand photographic education through YouTube?

LB: Lastly, perhaps I could ask how you feel about the term ‘photography’ in terms of what you do at the gallery, and outside of it. Is it particularly useful, or resilient, when photography no longer seems quite the clear-cut medium it was? Now it blurs into a whole range of other practices from light detection and ranging, to three-dimensional computer renders, and generative algorithms capable of creating original images without ever coming into contact with a camera.

KS: Photography was never a clear-cut medium, and it is no surprise it continues to be perplexing! I actually find the framing of photography immensely productive, with all its limits, and gives an important historical grounding to the debates. I’ve already mentioned that the tendency in our community to treat the photograph as a sign or picture has a tendency to render the computer interface invisible. Conversely, the computer sciences treat the photographic image as an uncomplicated and transparent window on the world, ignoring the politics of representation which photography scholars have unpacked. There is therefore a real need to create opportunities to escape our institutional silos and find ways of bringing commercial technologists, photographers, artists, scholars and our audiences into a productive dialogue. The challenge for both culturalists and technologists is to treat ‘the digital’ not as simply a tool but as a culture. ♦

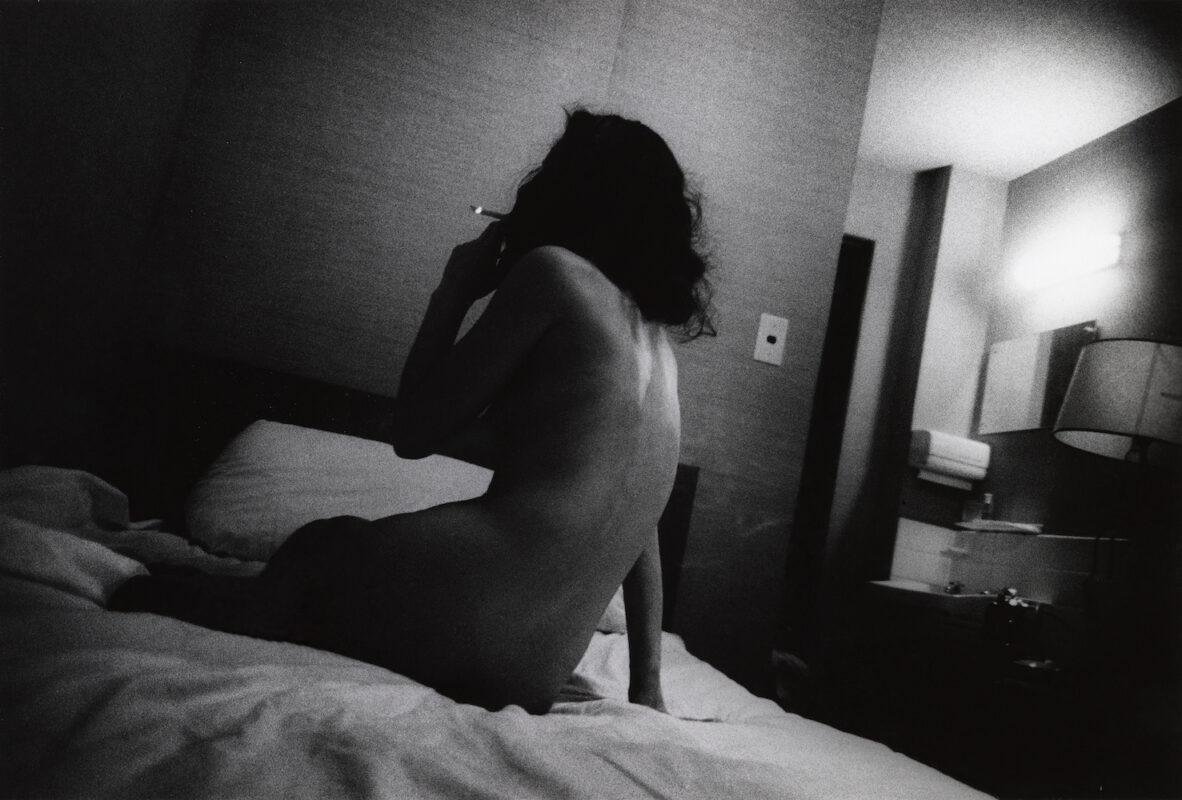

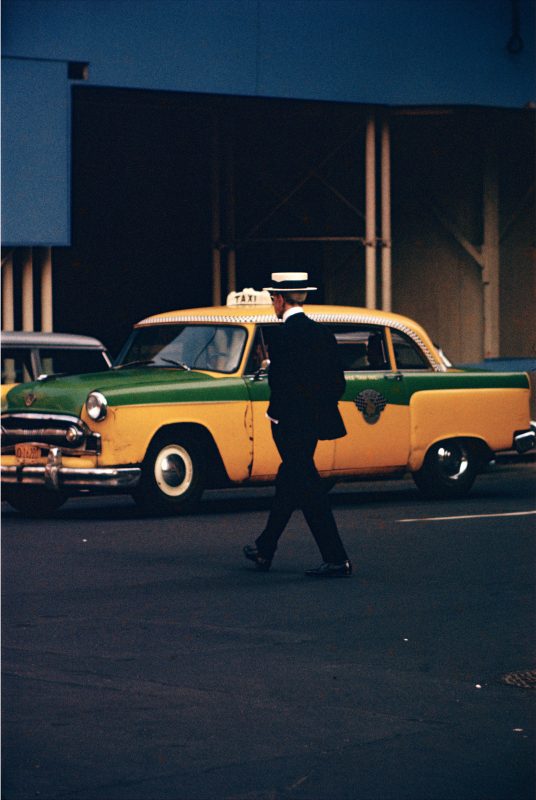

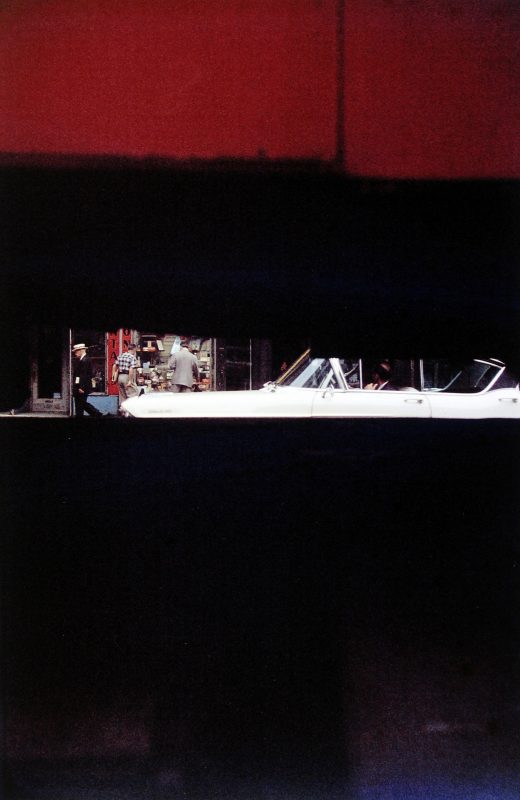

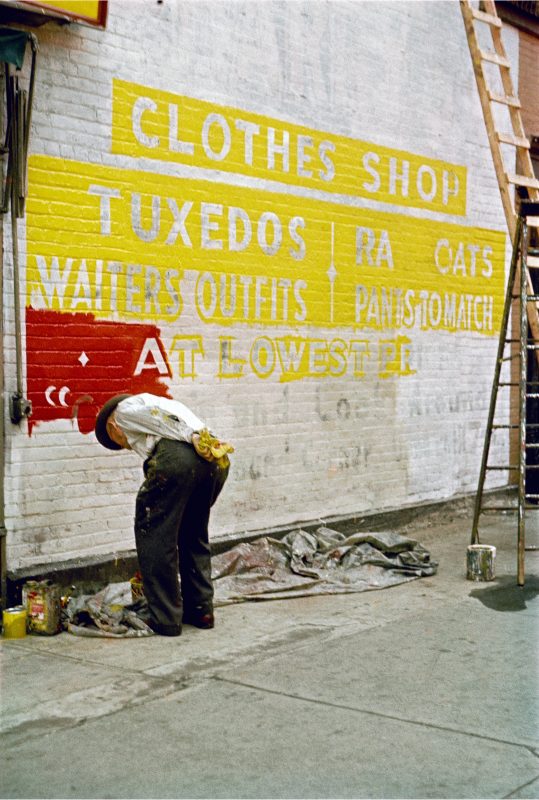

Image courtesy Katrina Sluis. © Simon Terrill