Thomas Sauvin

Silvermine

Essay by Gordon Macdonald

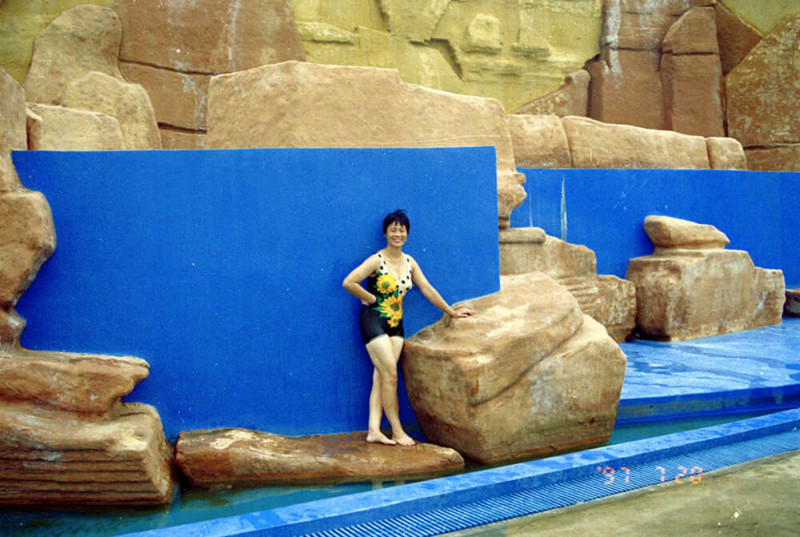

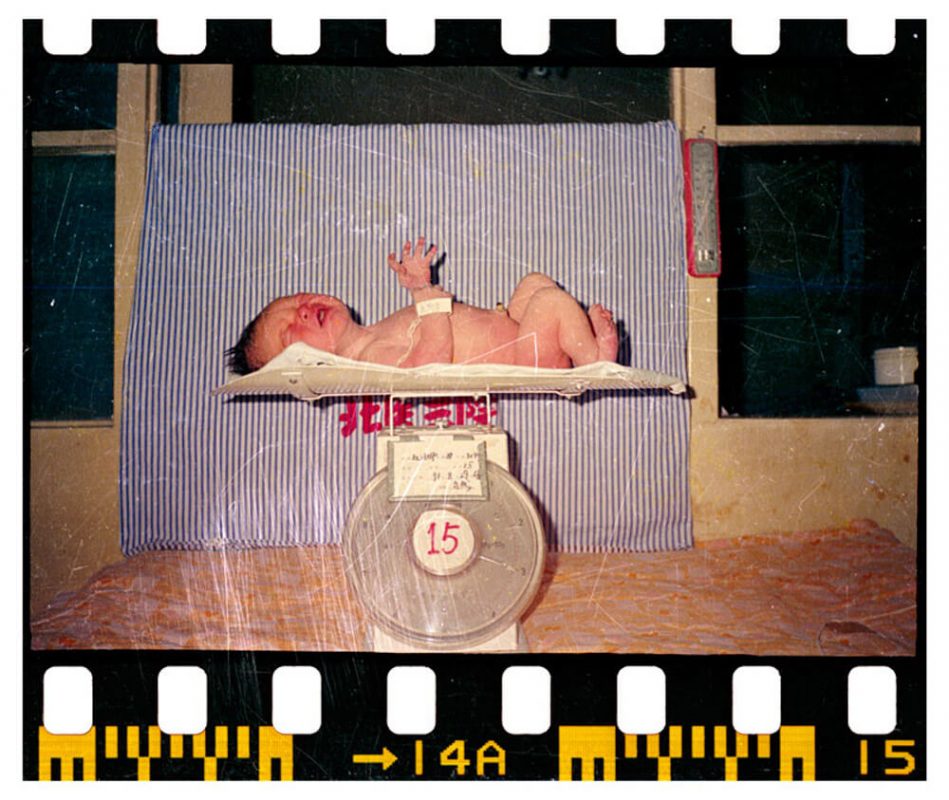

Beijing Silvermine, naturally and without artistic pretention, documents the experience of ‘ordinary’ people stepping out from the shadow of The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, as China accelerated towards becoming the world’s second largest economy and its people began to experience all of the consumer pleasures that go along with such wealth. The subjects of the photographs are pictured posing with refrigerators, telephones and TV sets; they are lying on the beach in Speedo trunks and visiting theme parks.

This is a vast and complex project by French archivist/artist Thomas Sauvin, though definitions become tricky and maybe moot here. In order to understand Sauvin’s truly monumental undertaking, it is useful to look at the process through which he has managed to collate and catalogue the discarded snapshots of China’s capital city. Silvermine is the result of more than four years work collecting, digitising and ordering what now amounts to over half a million negatives and transparencies retrieved from a Beijing recycling dump. The material has been recovered from the rubbish bags of Beijing citizens in several stages, and while it involves various different people, it is clear that it would no longer exist as photography were it not for Sauvin’s intervention and orchestration. The photography – presumably thrown out because the original owners have moved to digital photography, have died or moreover no longer see the value in keeping negatives – is recovered from the tip by an ‘illegal recycler’ and taken back to a small lock up where the necessary equipment for silver nitrate recovery is sited. It is kept in large rice bags waiting to be submerged in acid baths, which strip out the silver nitrate, leaving the film clear and the images lost. This is where Sauvin intervenes by buying the film at a Renminbi per kilo price. The recycler, one would imagine, has no time to follow an interest in the images, their content or their history. By the look of his dingy workshop and description of his working day, he cannot afford such pursuits – it looks a bleak day-to-day existence, and Sauvin must be an oddity to him, paying to save him the work of extracting the precious commodity that is his livelihood. Sauvin’s idea of the value of the material is, of course, more culturally-based, and he takes them from the ramshackle workshop to the more salubrious surroundings of his studio for initial interrogation on a gigantic light-table.

Sauvin chooses only snapshots and separates out those images that could have had commercial use, before taking them to the small home of his scanning technician, whose job it is to scan the pile of negatives and transparencies. Having completed the scanning, he then delivers them to Sauvin on a hard disc some weeks later. This is where Sauvin’s intervention, and the work of viewing, ordering and cataloguing starts in earnest. It is evidently a task of truly overwhelming proportions considering the sheer scale of the archive and the rigour he brings to it, but one which would be hard to stop short of completion. Indeed, Sauvin has envisioned the end of his pursuits, saying “I’ll stop collecting negatives when there are no more to collect. I get less and less of them every month and it is quite likely to be over soon. Eventually this project will witness the death of analog photography in China.”

Surprisingly, the real shock of Sauvin’s Silvermine is the familiarity, not the exoticism. The poses, leisure activities, clothes, home appliances, relationships, landscape, expressions, vehicles, theme parks or food do not differ all that much from the photographs found in a typical British family album from the 70’s and 80’s. It is sometimes the case that collections and studies such as these can slip unnervingly towards a cut-priced anthropology, where western eyes are cast over foreign cultures, at worst resulting in a bizarre form of neocolonialism. But, thankfully, there is everydayness in this project.

Sauvin also makes the archive accessible to Chinese artists to view, reassess and use with the aim of producing their own interpretations of the material. Notable Chinese artist LeiLei, in collaboration with Sauvin, is one such example. An animation, the images flit unremittingly from one to another, sometimes pointing out the happenstance, which occurs so regularly when this many photographs are collected from one place, or sometimes the oddity within individual photographs. It is all set to the soundtrack of the collected white noise of the city – electric hum, helicopters, road traffic, dripping, screeching, overwhelming sound – which, with the pace and intensity of the images filling your peripheral vision, leaves you spinning. Every so often in the film, titled Recycled, a print of one of the images appears, held at arm’s length by LeiLei, up to the landscape in which it was shot, leaving you in no doubt that you are looking at photographic constructs, and the edited extracts of peoples’ lives. Having watched the film a few times now, I have had to limit myself to one viewing a day for fear that my brain might combust as a result of its greed for the visual information the film is feeding it with – I feel like a compulsive eater at an all you can eat buffet. It is a completely enveloping sensory experience.

This archival project is not without context – comparisons could be made to Evidence by Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel; the epic Pictures from the Street (Bilder von der Straße) by Joachim Schmid, In Almost Every Picture by Eric Kessels (et al) or the magnificent Sputnik by Joan Fontcuberta – but Silvermine seems markedly different and unlike any archival project to have come before. There is a certain generosity to Sauvin’s non-curatorial approach and commitment to collecting and cataloging every image he possibly can. And, though some images necessarily creep to the top of the pile and become emblematic of the archive, Sauvin seems to treat every picture as equally important to the overall project. Silvermine, funded by the London-based Archive of Modern Conflict, seems genuinely to be about saving an important history that is in danger of being consigned to oblivion. If only the discarded images of every city could benefit from this process, but it is certainly well past the point of no return for analogue photography and far too late to start somewhere else. Maybe the next Silvermine will be made up of hard drives recovered from discarded computers, as digital files will surely soon be made redundant by the relentless march of technological change. ♦

Thomas Sauvin is a French photography collector and editor who currently lives in Beijing. Since 2006 he works exclusively as a consultant for the UK-based Archive of Modern Conflict, an independent archive and publisher, for whom he collects Chinese works, from contemporary photography to period publications to anonymous photography. A glimpse into this collection is presented in the photobook, Happy Tonite (2010). Sauvin has exhibited at Dali International Photography Festival, China; Open City Museum, Brixen, Austria; Singapore International Photography Festival, Singapore; and FORMAT International Photography Festival, Derby.

All images courtesy of the artist. © Thomas Sauvin